Abstract

Background

There are multiple existing and emerging therapeutic avenues for metastatic prostate cancer, with a common denominator, which is the need for predictive biomarkers. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has the potential to cost-efficiently accelerate precision medicine trials to improve clinical efficacy and diminish costs and toxicity. However, comprehensive ctDNA profiling in metastatic prostate cancer to date has been limited.

Methods

A combination of targeted and low-pass whole genome sequencing was performed on plasma cell-free DNA and matched white blood cell germline DNA in 364 blood samples from 217 metastatic prostate cancer patients.

Results

ctDNA was detected in 85.9% of baseline samples, correlated to line of therapy and was mirrored by circulating tumor cell enumeration of synchronous blood samples. Comprehensive profiling of the androgen receptor (AR) revealed a continuous increase in the fraction of patients with intra-AR structural variation, from 15.4% during first-line metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer therapy to 45.2% in fourth line, indicating a continuous evolution of AR during the course of the disease. Patients displayed frequent alterations in DNA repair deficiency genes (18.0%). Additionally, the microsatellite instability phenotype was identified in 3.81% of eligible samples (≥ 0.1 ctDNA fraction). Sequencing of non-repetitive intronic and exonic regions of PTEN, RB1, and TP53 detected biallelic inactivation in 47.5%, 20.3%, and 44.1% of samples with ≥ 0.2 ctDNA fraction, respectively. Only one patient carried a clonal high-impact variant without a detectable second hit. Intronic high-impact structural variation was twice as common as exonic mutations in PTEN and RB1. Finally, 14.6% of patients presented false positive variants due to clonal hematopoiesis, commonly ignored in commercially available assays.

Conclusions

ctDNA profiles appear to mirror the genomic landscape of metastatic prostate cancer tissue and may cost-efficiently provide somatic information in clinical trials designed to identify predictive biomarkers. However, intronic sequencing of the interrogated tumor suppressors challenges the ubiquitous focus on coding regions and is vital, together with profiling of synchronous white blood cells, to minimize erroneous assignments which in turn may confound results and impede true associations in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer is the most commonly detected male cancer in Europe and the third major cause of cancer-related death among men [1]. Although the majority of metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancers (mHNPCs) demonstrate a reliable response to initial androgen deprivation therapy which targets AR signaling, progression to a castration-resistant state is inevitable. However, the treatment landscape for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is evolving with the recent approval of several new drugs translating to an increased overall survival [2,3,4,5,6]. Multiple additional avenues exist as genomic profiling of metastatic tissue revealed that the majority of mCRPC patients harbor clinically relevant alterations beyond the AR signaling pathway [7].

The most promising non-approved treatment avenue in metastatic prostate cancers (mPCs) exploits synthetic lethality in treating homologous recombination-deficient cancers with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors [8]. Approximately one fifth of mCRPC carry mutations in DNA repair genes [7]. However, the mutational signatures of biallelic inactivation are heterogeneous between different DNA repair genes [9], and future studies are therefore needed to determine which genes are associated with a response to PARP inhibition. Approximately 3% of mPC are driven by microsatellite instability (MSI) [7, 10]. Pembrolizumab recently became the first drug to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration based on the MSI phenotype, irrespective of tumor type [11]. Although checkpoint blockade did not confer a survival advantage as compared with placebo for chemotherapy-relapsed mCRPC [12], anecdotal cases have been reported to display partial or complete responses [10, 13,14,15].

The emergence of additional drugs, both towards common and rare mPC phenotypes such as PTEN-deficient [16, 17] and neuroendocrine cancers [18], raises questions of how to efficiently translate the multitude of treatment options to improved patient outcomes. The genomic heterogeneity of mCRPC [7] and, in turn, the low response rates of currently approved drugs [2,3,4,5, 19, 20] argue for the urgent need of predictive biomarkers. Ineffective trial-and-error decisions inevitably lead to unnecessary side effects and unsustainable costs [21]. The AR splice variant 7 (AR-V7) [22] demonstrated promising results as a negative response biomarker for androgen receptor signaling inhibitors. However, follow-up studies have been unable to validate the initial clear-cut finding [23, 24], and although AR-V7 is clearly prognostic, clinical implementation remains debated due to (1) lack of treatment options for AR-V7-positive patients and (2) lack of data from a prospective clinical trial demonstrating the predictive power of AR-V7 for treatment selection [25]. Recently, Scher and colleagues demonstrated increased survival for AR-V7-positive patients receiving taxanes in a blinded retrospective multicenter study [26]. However, AR-V7 assay positivity and taxane therapy were both correlated to tumor burden, obscuring interpretation and further highlighting the need for a prospective randomized clinical trial to determine if AR-V7 can be applied as a predictive biomarker [27].

The lack of predictive biomarkers is in part due to the difficulty of obtaining temporally matched metastatic tissue as the majority of mPCs metastasize to the bone. Multiple studies on the acquisition of tumor tissue with or without direct image guidance report a range of success rates [28,29,30,31]. A recent effort, focusing on methodological improvements, obtained > 20% cell content in the majority of bone biopsies [32]. Circulating tumor DNA is a viable alternative to metastatic tissue with demonstrated high fractions of ctDNA [33,34,35,36] enabling sensitive detection of somatic variation, and direct comparisons to metastatic tissue have revealed high concordance [33, 37, 38]. Circulating tumor DNA has several advantages as sampling through simple blood draws is fast, cost efficient, and without side effects and allows for longitudinal monitoring and the detection of multiple resistance alleles during therapy [38, 39].

Although ctDNA has the potential to accelerate biomarker-driven trials in mPC, several questions remain unanswered, e.g. if it is possible to detect MSI directly from liquid biopsies and how ctDNA fractions correlate to line of therapy. The ctDNA fraction determines the sensitivity to detect somatic variation which in turn has consequences for the design of prospective biomarker studies relying on liquid biopsies. Here, we present a retrospective analysis of 217 cases and 364 blood samples covering the entire spectrum of mPC. The purpose of this study was to gather information relevant for future liquid biopsy-driven biomarker studies with a focus on (1) how ctDNA fractions vary from mHNPC to end stage castration-resistant disease; (2) a rationale for how to treat samples with low ctDNA fraction; (3) the relative impact of different types of somatic variation, affecting the sequencing strategy; (4) the detection of potentially predictive biomarkers; (5) and finally, how clonal expansions in the hematopoietic stem cells [40,41,42,43] impact liquid biopsy profiling.

Methods

A detailed description of the methods is provided in Additional file 1: Supplemental methods. In brief, mPC patients were recruited in an all-comer cohort (n = 217), ranging from hormone-naïve to castration-resistant, between 2014 and 2017 with histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma (Table 1). Blood samples (n = 364) were collected at the start of a new line of therapy (defined as “baseline” sample) or during a particular systemic therapy (defined as “follow-up” sample). The complete study cohort (n = 217) encompassed patients recruited as part of the ProBio (Prostate Biomarkers) study (n = 72, Stockholm, Sweden) and abiraterone- or enzalutamide-treated patients (n = 145) recruited to the CORE-ARV-CTC study (Antwerp, Belgium). The original purpose of the CORE-ARV-CTC cohort was to investigate if profiling androgen receptor splice variants in circulating tumor cells (CTCs) may predict response to enzalutamide and abiraterone treatment. The result of this analysis together with somatic alterations in AR and TP53 is presented in a separate manuscript [24]. Additionally, anonymous healthy donor blood (n = 36) was collected (Stockholm, Sweden). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, after approval was acquired by ethical committees in Belgium (Antwerp University Hospital, registration number: B300201524217) and Sweden (Karolinska University Hospital, registration number: 2016/101-32). All patients provided a written informed consent document. Plasma was enriched from 2 × 10 ml (ProBio patients) or 4–5 ml (CORE-ARV-CTC patients) EDTA blood and stored at − 80 °C within the same working day, allowing for high-quality ctDNA profiling [44]. Germline DNA was extracted from leftover EDTA blood. In addition, for 340 out of 364 ctDNA-analyzed blood samples, an additional blood sample was collected in a CellSave tube and shipped to the GZA Sint-Augustinus (Antwerp, Belgium) for CTC enumeration within 72 h on the FDA-cleared CellSearch platform (Menarini Silicon Biosystems, Italy), as previously described [45]. Upon isolation, 0.1–50 ng of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and 50 ng of germline DNA were used to create the sequencing libraries (ThruPLEX Plasma-seq kit, Rubicon Genomics, USA). Cell-free DNA profiling was performed with a mix of low-pass whole genome sequencing and hybridization-capture targeted sequencing (SeqCap EZ system, Roche Nimblegen, USA). Germline samples were only processed by the latter. The capture designs and their targeted regions are described in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Low-level processing of the sequencing data was performed as previously described [36] and analyzed as described in detail in Additional file 1: Supplemental methods, which allowed for identification of pathogenic germline variants, copy-number alterations (CNAs), small mutations, and structural variation in unique regions in the human genome commonly mutated in prostate cancer (bioinformatic tools and settings are summarized in Additional file 3: Table S2). The detection of somatic alterations, which was copy-number adjusted, allowed the estimation of tumor burden (ctDNA fraction, the fraction of cfDNA molecules originating from the cancer cells). Where somatic CNA analysis suggested a higher tumor burden, it was instead calculated from the CNA profile. Additionally, the incorporation of microsatellites in the comprehensive capture design allowed the evaluation of microsatellite instability (MSI). Finally, the analysis of patient-matched cfDNA and germline DNA samples, compared to a merged file of all healthy donor blood samples as a control, allowed the interrogation of clonal hematopoiesis. Statistical analysis was performed in R (v3.3.2) [46].

Results

Liquid biopsy profiling of metastatic prostate cancer

Comprehensive cfDNA profiling was performed on 217 mPC patients (Table 1). Single nucleotide variants, copy-number alterations (CNAs), and genomic structural rearrangements were interrogated using a combination of in-solution hybridization capture-based and low-pass whole genome sequencing. An evolution of capture designs was applied as the project progressed, from a pan-cancer to a prostate-specific approach to cost-efficiently maximize the information content (Additional file 2: Table S1). The comprehensive designs were aimed at progression samples with high tumor burden whereas the smaller designs were tailored for cost-efficient deep sequencing. However, to increase the sensitivity to detect, e.g., intronic structural variation in AR, the majority of samples were processed with both a comprehensive and a smaller design (Additional file 4: Table S3). The data was subsequently merged before variant calling. The average coverage, taking merging into account, was 814× (interquartile range 251–965) for cfDNA and 445× (interquartile range 371–533) for germline DNA. Data from all samples is presented here, where the number of relevant samples is described for each section (Additional file 5: Table S4). In total, 364 plasma samples from 217 mPC patients were profiled. Circulating tumor cell enumeration using the CellSearch platform was performed from synchronous blood draws on 340 of the 364 plasma samples.

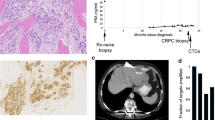

Circulating tumor DNA fraction correlation to line of therapy

Circulating tumor DNA was detected in the majority of baseline samples (85.9%, Additional file 6: Figure S1). However, as the fraction of ctDNA in the cfDNA influences the sensitivity to detect somatic variation, we investigated if tumor burden correlated to line of therapy and blood draw timing (Additional file 7: Table S5). Comparing baseline ctDNA fractions at different lines of therapy, a significant increase was present between first- and second-line mCRPC and third- and fourth-line mCRPC (Fig. 1). The ctDNA fractions were significantly lower, comparing baseline and follow-up samples for mHNPC and first-line mCRPC (Additional file 6: Figure S2). The differences were not statistically significant for later lines of therapy. The CTC counts were correlated to the ctDNA fraction estimate (rho = 0.7, p < 0.0001) (Additional file 6: Figure S3) and mimicked the ctDNA pattern in relation to line of therapy (Fig. 1, Additional file 6: Figure S2).

Tumor burden at different lines of therapy. a Violin plot of the circulating tumor cell counts per 7.5 ml of blood using the CellSearch platform partitioned according to line of therapy. The black horizontal lines within the violin plots denote the median of the density estimate. Blue points represent the circulating tumor cell counts in individual blood samples. A one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to investigate if the baseline samples of, for example, mCRPC1 had lower tumor burden than mCRPC2. Y-axis: log10 transformed circulating tumor cell counts. X-axis: line of therapy. b as a but for circulating tumor DNA fraction. Y-axis: circulating tumor DNA fraction. In total, 364 blood samples from 217 cases are displayed here; however, only 340/364 had a successful circulating tumor cell count. The dashed lines at 0.02, 0.10, and 0.20 denote the cutoffs to reliably detect point mutations, loss of heterozygosity, and homozygous deletions, respectively. Abbreviations: mHNPC[number], metastatic hormone naïve prostate cancer and line of therapy; mHSPC[number], metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer and line of therapy; mCRPC[number], metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and line of therapy; _B, baseline, blood samples collected at start of a new systemic therapy; _F, follow-up, blood samples collected during a systemic therapy; Nbr, number of cell-free DNA samples profiled in each category

Detection of microsatellite instability from cell-free DNA

Microsatellites were targeted and sequenced to enable MSI-phenotype detection directly from cfDNA (Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 5: Table S4). Using an in-house cohort of colorectal cancer samples (Additional file 6: Figure S4), in silico dilution with germline DNA demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 99% specificity to detect MSI at 10% tumor purity and 10% unstable microsatellites with the mSINGS algorithm [47]. Applying mSINGS on ≥ 10% ctDNA fraction samples identified four cases with MSI out of 105 investigated (Fig. 2). The proportion of MSI-positive cases detected from ctDNA is concordant with a previous study based on whole-exome sequencing of metastatic tissue samples (two-sided Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.721) [7].

Detection of microsatellite instability from cell-free DNA. Microsatellite unstable tumors were identified from 121 samples (105 unique patients) with ≥ 0.1 circulating tumor DNA fraction by plotting the number of mutations (Y-axis, including intronic and synonymous variants) versus the fraction of unstable microsatellite loci (X-axis). Indels and single nucleotide variants are kept separate for each sample, colored according to the right legend. The dashed vertical line at 0.10 fraction unstable microsatellites denotes the cutoff to reliably detect microsatellite instability. Two separate cell-free DNA samples were profiled for P-GZA003, and both demonstrated microsatellite instability. Note that although individual P-KLIN014, sample 20170058, demonstrated > 0.1 fraction unstable microsatellite loci, it was classified as microsatellite stable. The sample had a high circulating tumor DNA fraction (0.80), lacked an increase in number of mutations and displayed high copy-number burden, indicative of a chromosomal instability phenotype

Intronic sequencing of key tumor suppressors and biallelic inactivation

Prostate cancer is mainly driven by CNAs, commonly generated through chained structural rearrangements. Chained events cause the majority of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions [48], also observed in our data (Fig. 3, Additional file 6: Figure S5). To allow detection of structural rearrangements, capture probes were designed towards the non-repetitive intronic and exonic regions of PTEN, RB1, and TP53 in the prostate-specific comprehensive design (CP design, Additional file 2: Table S1, Additional file 5: Table S4, Additional file 8: Table S6, Additional file 6: Figure S6). Structural rearrangements, mutations, and copy-number alterations were investigated in 165 cfDNA samples from 135 study participants profiled with the CP design that passed the internal quality control for structural variant calling (Additional file 1: Supplemental methods, Additional file 5: Table S4). Seventy-one samples (71/165, 43.0%) from 59 men (59/135, 43.7%) had a ctDNA fraction ≥ 0.2, where all classes of somatic variation were detectable. Biallelic inactivation, through clonal high-impact variation, occurred in 47.5% (28/59), 20.3% (12/59), and 44.1% (26/59) of patients in PTEN, RB1, and TP53, respectively. After excluding the MSI samples (carrying high-impact passenger mutations in multiple genes), all samples with a clonal high-impact variant also harbored a second event with only one exception: two samples were profiled for patient P-00030277 and both revealed a 392-kb deletion encompassing exon 9–10 of TP53 without any observable second hit.

Exonic and intronic profiling of circulating tumor DNA. The non-repetitive sequence was captured for the entire gene body of TP53, PTEN, and RB1 in 165 cell-free DNA samples from 135 men. The somatic variants found in the 152 cell-free DNA samples from 124 men with detectable circulating tumor DNA are shown here. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions or structural rearrangements in TMPRSS2 or ERG are also shown. The upper panel displays the circulating tumor DNA fraction. The dashed lines at 0.02, 0.10, and 0.20 denote the cutoffs to reliably detect point mutations, loss of heterozygosity, and homozygous deletions, respectively. Bottom panel, heatmap of the somatic alterations detected from circulating tumor DNA profiling. Type of alteration is coded according to the bottom legend. For visualization purposes, up to two mutations or structural variants (forward and backslashes) are displayed per patient. Triangles and boxes represent single nucleotide variants and indels, respectively. Subclonal mutations are defined as having an allele frequency < 1/4 of the circulating tumor DNA fraction. The same definition was applied to structural variants after median allele frequency adjustment with respect to the mutations. Synonymous point mutations are not displayed here. Variants of unknown significance are non-synonymous single nucleotide variants outside hotspots, not annotated as pathogenic in variant databases. Structural variants of unknown significance are, for example, confined to a single intron, without affecting neighboring exons. X-axis: cell-free DNA samples sorted according to the circulating tumor DNA fraction. Patients with multiple samples are colored in blue. The asterisk indicates samples with microsatellite instability. Samples described in the main text are connected with lines

Clonal dynamics during treatment

Subclonal high-impact variation was detected in multiple patients. Both samples of P-GZA006 revealed subclonal TP53 mutation accompanied by subclonal deletion (Fig. 3). Before the start of abiraterone therapy, sample 20160759 of patient P-GZA4777 carried two subclonal TP53 mutations (hotspot and frameshift), a subclonal translocation in PTEN, and a weak AR amplification (Additional file 6: Figure S7A). At progression (sample 20160890), the hotspot TP53 variant, PTEN translocation and the AR amplification were undetectable. However, the TP53 frameshift increased in allele fraction and a new structural deletion in TP53 was found, in line with TP53 loss being associated with rapid progression [49]. P-KLIN003 also experienced change in clonal composition during abiraterone therapy (Additional file 6: Figure S7B). At baseline, two TP53 mutations were detected. After therapy, the two displayed different behavior, decreasing and increasing in allele fraction. The progressing clone also presented with TP53 loss of heterozygosity and multiple structural variants in AR. Patient P-00039325 had high ctDNA fraction despite being on androgen deprivation therapy for 3 weeks. Following docetaxel treatment, P-00039325 progressed after 215 days with a translocation in BRCA2 and concomitant loss of heterozygosity (Additional file 6: Figure S7C). In addition, an AR amplification and intra-AR structural variation were detected.

Continuous evolution of somatic variation in the androgen receptor

Comprehensive profiling of AR, including intronic sequencing, was performed in 275 mCRPC plasma samples from 177 individuals (Fig. 4a, Additional file 5: Table S4). In total, 45.8% (126/275) of the samples and 50.3% (89/177) of the patients harbored one or more variants in AR (high-impact mutation, structural variant, or amplification) in at least one cfDNA sample (Additional file 8: Table S6). Intra-AR structural variation was closely correlated to amplification, and only 3/51 patients (P-GZA4045, P-GZA4120, P-U001) carried intra-AR structural variation without an accompanying amplification. Structural variation was detected in another three patient samples without amplification (P-AZSJ022, P-KLIN002, P-UZA002), but weak amplifications were found in other samples from the same individuals, taken at other occasions. The fraction of patients with structural variation in AR correlated to line of therapy, ranging from 15.4% during first-line mCRPC therapy to 45.2% in the fourth line. Overall, the percentage of individuals with any alteration in AR increased from 37.4% in the first line to 76.9% in the fourth line, indicating a continuous evolution of AR during the course of the disease (Fig. 4b).

Androgen receptor alterations. Comprehensive profiling of AR was performed in 275 cell-free DNA samples from 177 mCRPC patients. a The upper panel displays the circulating tumor DNA fraction. The dashed lines at 0.02, 0.10, and 0.20 denote the cutoffs to reliably detect point mutations, loss of heterozygosity, and homozygous deletions, respectively. Bottom panel, heatmap of the mutational landscape detected in the androgen receptor from circulating tumor DNA profiling. Type of alteration is coded according to the bottom legend. For visualization purposes, only samples with an alteration are shown here (126 samples from 89 individuals). Up to two mutations or structural variants (forward and backslashes) are displayed per sample. X-axis: cell-free DNA samples sorted according to the number of alterations detected. Patients with multiple samples are colored in blue. The asterisk indicates samples with microsatellite instability. b The fraction of patients with alterations in the androgen receptor is categorized by type of alteration and line of therapy. Only high-impact mutations, e.g., hotspot mutations, are shown here. Intra-AR structural variation is colored according to the legend in a. The rightmost bar plot represents the fraction of patients with any alteration in the androgen receptor. Abbreviations: mCRPC[number], metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and line of therapy; _B, baseline; Nbr, number of samples profiled

Alterations in DNA repair deficiency genes

Genes associated with DNA repair deficiency and commonly mutated in prostate cancer were targeted for mutations and deletions (Additional file 2: Table S1). Sequencing of germline DNA revealed high-impact variants in 8.92% (ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, and CHEK2), similar to recent reports [50,51,52]. However, only 2/213 (excluding four germline DNA samples that failed processing) carried pathogenic BRCA2 mutations, significantly less than Pritchard et al. [51] and Mandelker et al. [52] (two-sided Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.00329, p = 0.00129, respectively; Additional file 9: Table S7). Both reported multiple occurrences of Ashkenazi Jewish founder mutations such as the BRCA2 p.Ser1982Argfs*22, not observed in this report. Coverage was manually inspected using the integrative genomics viewer [53] which excluded technical causes. This suggests differences in the underlying population demographics. Excluding MSI-positive cases, 18 (8.29%) individuals had somatic biallelic inactivation of a DNA repair gene, whereas 39 (18.0%) had one detectable alteration (Fig. 5, Additional file 8: Table S6). Note, however, that the intronic regions were not targeted in the current version of these capture designs rendering structural variation undetectable, except close to exons or baits designed for CNA purposes.

Alterations in genes associated with DNA repair deficiency. The upper panel displays the circulating tumor DNA fraction. The dashed lines at 0.02, 0.10, and 0.20 denote the cutoffs to reliably detect point mutations, loss of heterozygosity, and homozygous deletions, respectively. Bottom panel, heatmap of the mutational landscape detected from circulating tumor DNA profiling of 327 cell-free DNA samples from 217 individuals. For visualization purposes, only the 76 samples with a relevant alteration are shown here. Type of alteration is coded according to the bottom legend. Up to two mutations or structural variants (forward and backslashes) are displayed per patient. Triangles and boxes represent single nucleotide variants and indels, respectively. Subclonal mutations are defined as having an allele frequency <1/4 of the circulating tumor DNA fraction. The same definition was applied to structural variants after median allele frequency adjustment with respect to the mutations. The BRCA2 structural variant of patient P-00039325, sample 3167424, was classified as borderline subclonal although relevant in the progressing clone after chemohormonal treatment (Additional file 6: Figure S7C). Synonymous point mutations are not displayed here. Variants of unknown significance are non-synonymous single nucleotide variants outside hotspots, not annotated as pathogenic in variant databases. Structural variants of unknown significance are for example confined to a single intron, without affecting neighboring exons. X-axis: cell-free DNA samples sorted according to the number of alterations detected in each gene in alphabetical order. Patients with multiple samples are colored in blue. The asterisk indicates samples with microsatellite instability

Clonal hematopoiesis causes false positive findings

Aberrant blood cell populations [40,41,42,43] have the potential to confound ctDNA mutational profiles when performed without matched blood DNA as a control. To assess the potential impact and prevalence of genetically aberrant blood cell expansions in our cohort, we investigated copy-number and mutational data for indications of aberrations present in both cfDNA and white blood cell (WBC) DNA. We observed, in separate patients, four cases of large arm-level copy-number alteration (chr 11, 13, and 20) in WBC with coverage ratio and single nucleotide polymorphism allele ratio suggesting a cellularity between 40 and 65% and a focal CCND1 amplification with coverage ratio 1.57, and all were similarly observed in the cfDNA. Putative hematopoietic somatic point mutations were interrogated in WBC DNA using pooled healthy donor DNA as control and excluding variants exceeding 25% allele ratio and outside known somatic hotspots as likely germline. Thirty-seven protein-altering variants were observed in another 29 patients and could be validated in patient-matched cfDNA, including hotspot mutations in AKT1, BRAF, CTNNB1, DNMT3A, NRAS, SF3B1, and TP53 (Fig. 6). In summary, 40 false positive variants in 31 patients (14.6%) would have been included in ctDNA mutational profiles if matched WBC had not also been sequenced.

Clonal hematopoiesis. Presence of clonal expansions in the white blood cell compartment was investigated by somatic mutation (single nucleotide variants and indels) analysis. Somatic mutations, supporting existence of clonal hematopoiesis, were identified in germline DNA extracted from white blood cells by using a pool of healthy donor DNA as reference and subsequently validated in cell-free DNA from the same individual. For each mutation, the amino acid position and total number of amino acids are given. Patients with multiple mutations are labeled with sample donor ID. X-axis: variant allele frequency. Y-axis: individual mutations sorted according to allele frequency in white blood cells and individual. The inset legend explains the type and the source of each variant

Discussion

Genomics-guided therapy selection is arguably the most promising avenue to remedy trial-and-error treatment decisions and the accelerating costs of drugs [21]. However, the utility of tumor profiling is currently limited in mPC due to the lack of validated predictive biomarkers. Liquid biopsies have the potential to act as a tissue substitute and cost-efficiently accelerate trials designed to identify predictive biomarkers. Therefore, we set out to comprehensively profile cfDNA samples in mPC, encompassing mHNPC to mCRPC, to gain knowledge relevant for applying ctDNA in a clinical trial context. Although this study was not designed as a predictive or prognostic biomarker study, our data represents a valuable resource for the mPC ctDNA field. We demonstrate the capability of ctDNA-based analysis, but at the same time highlight the challenges which include, but are not limited to, performing analysis where the somatic alterations may originate from multiple independent sources and ctDNA fraction may be low. In addition, we addressed several unanswered research questions of which the key findings are as follows: (1) ctDNA fractions increased gradually from the first to fourth line of therapy. Baseline samples had higher ctDNA fraction compared to follow-up samples, but the difference became non-significant after the second line of mCRPC therapy; (2) in samples with high tumor burden, inactivation of key tumor suppressors was biallelic rather than monoallelic, with only one exception, providing a rationale for assuming a second hit in low ctDNA fraction samples with insufficient sensitivity to detect the second hit; (3) clonal high-impact structural variation is twice as common as point mutations, which challenges the traditional focus on coding regions; (4) the three potentially clinically valuable biomarkers in mPC, microsatellite instability, mutations in genes associated with DNA repair deficiency and AR aberrations were detected at expected rates; (5) clonal hematopoiesis occurs frequently, demanding synchronous WBC profiling to avoid false positive variant calls.

Due to the genomic diversity of metastatic cancer, resistance will always arise to single-agent therapies where the duration of response is correlated to the number of cancer cells in a patient [54]. Towards end-stage disease, progression will occur more rapidly, regardless of therapy, with the exception of extreme responders to immunomodulators [14]. Molecular biomarker-driven clinical trials are commonly targeting patients where no approved treatment options remain, although primary outcomes may be hard to achieve if disease burden is too high [55]. Consequently, tumor burden as ctDNA fraction or CTC counts is strongly correlated to conventional outcome measurements [49, 56]. Recently, simple cfDNA concentration estimates were demonstrated to prognosticate patients in a retrospective analysis of two phase III clinical trials [57]. Here, cfDNA concentration was strongly correlated to ctDNA fraction (Additional file 6: Figure S8) suggesting that cfDNA concentration estimation is a surrogate for ctDNA fraction.

Tailored treatment, based on tumor profiling, therefore has the greatest potential early in the course of the disease. Paradoxically, we find that liquid biopsies carry more information towards end-stage disease and currently harbor limited information in a significant fraction of patients starting first- and second-line mCRPC therapy due to low ctDNA fraction (Fig. 1). The tumor burden increased with new systemic (baseline) treatments, from the first to second line and third to fourth. We could not detect a significant difference between second and third baseline samples, likely reflecting the heterogeneity of the treatment sequencing and responses in this all-comers cohort. Comparing the baseline samples, the fraction where it was possible to identify homozygous deletions increased steadily from one third (33/99, before start of first systemic mCRPC treatment) to approximately 50% (59/126, before start of second/third systemic mCRPC treatments) and finally to more than two thirds (11/15, before start of fourth systemic mCRPC treatment). As a consequence, the fraction of patients with BRCA2 homozygous deletion detected here (1.38%, 3/217) was lower than previously reported from two studies analyzing tumor tissue from metastatic patients (2.67%, 4/150 and 4.54%, 5/110) [7, 58]. However, the difference was not statistically significant (two-sided Fisher’s exact test: p = 0.450 and p = 0.124, respectively).

A potential solution for the low ctDNA fraction samples may be a complementary approach using CTCs to gain insight into ploidy and CNA and ctDNA for mutations and structural rearrangements. However, there are some limitations: we show that CTC counts correlate with ctDNA fraction (Additional file 6: Figure S3), and patients with low ctDNA fraction starting first- and second-line mCRPC therapy, with few exceptions, have low CTC counts (Additional file 6: Figure S9); previous work demonstrates poor success rate (~ 10%) in obtaining high-quality CTC sequencing data from isolated cells [59, 60] necessitating multiple 10-ml blood tubes for CTC analysis in first- and second-line patients. However, recent improvements in harvesting metastatic tissue [32] may provide a fallback if ctDNA profiling fails to identify any relevant biomarkers. As the success rate of harvesting high-quality metastatic tissue is also correlated to tumor burden [29, 30], prospective validation is needed to establish the most feasible approach.

The inherent challenges to complement ctDNA profiling inspired us to investigate the necessity of observing a second hit to infer tumor suppressor deficiency. By deep sequencing of all non-repetitive intronic and exonic regions in TP53, PTEN, and RB1 in high ctDNA fraction samples, we investigated whether detection of one clonal high-impact variant is adequate to infer biallelic inactivation. Out of 71 samples in 59 men with ≥ 0.2 ctDNA fraction, 47.5%, 20.3%, and 44.1% harbored biallelic inactivation of PTEN, RB1, and TP53, respectively (Fig. 3). Only one patient carried a clonal high-impact variant, a deletion in TP53, without a detectable event on the other allele. These data are encouraging as a large fraction of TP53 was not possible to sequence due to repetitive DNA (Additional file 6: Figure S6). The observation is consistent with exome sequencing of 150 mCRPC tissues which revealed that biallelic inactivation always had occurred if a high-impact event was observed in a key tumor suppressor such as PTEN or RB1 [7]. Interestingly, residual breakpoints remained in 5/17 samples with a homozygous deletion in PTEN, which is detectable, even when tumor burden is low.

The comprehensive profiling of AR surprisingly revealed that 11 out of 85 amplified mCRPC cfDNA samples harbored hotspot mutations in AR. However, concomitant presence of amplification and mutations in a low fraction of cases has previously been described [34, 49]. Speculatively, the multiple existing therapies towards the AR signaling pathway will exert selection pressure differently. This will lead to a complex AR phenotype, where for example an amplified AR is first detectable after first-line androgen deprivation therapy. Subsequent abiraterone treatment may give rise to specific point mutations causing the simultaneous presence of both mutations and amplifications in AR. These speculations are supported by recently published data [49] demonstrating that AR amplifications are not prognostic in the context of abiraterone or enzalutamide treatment, causing a selective pressure on other AR and non-AR alterations as a consequence of therapy.

The advances in targeted sequencing of cancer have rapidly been adopted by multiple companies and transformed into commercially available ctDNA tests [61,62,63]. Two of these platforms were recently compared with surprisingly low concordance [64]. The lack of accompanying white blood cell germline profiling makes it hard to separate germline variation from somatic [65] and impossible to distinguish clonal hematopoiesis [40,41,42,43] from ctDNA unless the ctDNA fraction is high with distinct features of the disease, e.g., the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. In our study, 14.6% of patients harbored clonal expansions in the WBC compartment. Their somatic alterations, detected in germline DNA, were validated in cfDNA from the same individual. However, absolute confirmation of the cell of origin for clonal hematopoiesis events would require investigations involving fluorescence-activated cell sorting of the WBC populations followed by Sanger sequencing or preferably single-cell sequencing, which is beyond the scope of this study. As the targeted sequencing applied here only covered 60 out of 327 driver mutations associated with clonal expansions in the blood [41], the majority of men with mCRPC probably suffer from clonal hematopoiesis. A recent report used digital droplet PCR to investigate hotspot mutations in three genes, commonly mutated in hematopoietic malignancies, in WBC DNA from patients previously profiled with a commercial cfDNA assay [66]. A large fraction of the mutations was detected in the WBC DNA, corroborating our conclusions that to avoid false positive variant calls, sequencing of WBC DNA should be undertaken to the same or higher depth as the cell-free DNA. We therefore discourage the use of commercial assays that only analyze cfDNA from plasma.

Although multiple potentially predictive biomarkers have been reported for metastatic prostate cancer, no level 1 evidence currently exists from prospective randomized clinical trials. Based on our experience to date, we consider ctDNA profiling to be at Technology Readiness Level 7 according to the definition applied in the Horizon 2020 calls [67]. We have therefore initiated a prospective outcome-adaptive, multi-arm, open-label, multiple-assignment randomized biomarker-driven trial in patients with mCRPC where ctDNA profiling will be applied to identify somatic alterations (ProBio, EudraCT Number 2018-002350-78). The goal of the trial is to determine whether treatment choice based on a biomarker signature can improve progression-free survival compared to standard of care in patients with mCRPC and to evaluate the predictive capability of the investigated biomarker signatures.

Conclusions

This study strengthens the accumulating evidence that ctDNA profiling mirrors the somatic alteration landscape from metastatic tissue by demonstrating, for the first time, that the MSI phenotype may be detected directly from cell-free DNA. To enable acceleration of clinical trials through ctDNA analysis, intronic sequencing of tumor suppressors in combination with synchronous profiling of white blood cells must be applied to prevent inaccurate somatic variant calls, which in turn may reduce the power to identify predictive biomarkers.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

Androgen receptor

- AR-V7:

-

AR splice variant 7

- cfDNA:

-

Cell-free DNA

- CNA:

-

Copy-number alteration

- CTC:

-

Circulating tumor cell

- ctDNA:

-

Circulating tumor DNA

- mCRPC:

-

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

- mHNPCs:

-

Metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancers

- mPC:

-

Metastatic prostate cancer

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

- PARP:

-

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JWW, Comber H, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–403.

Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, Loriot Y, Sternberg CN, Higano CS, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:424–33.

de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005.

Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin M-E, Sternberg CN, Miller K, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–97.

Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, de Souza P, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:138–48.

Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O’Sullivan JM, Fosså SD, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–23.

Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu Y-M, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera J-M, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–28.

Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, Miranda S, Mossop H, Perez-Lopez R, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–708.

Polak P, Kim J, Braunstein LZ, Karlic R, Haradhavala NJ, Tiao G, et al. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1476–86.

Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23:703–13.

Commissioner O of T. Press Announcements - FDA approves first cancer treatment for any solid tumor with a specific genetic feature. Office of the Commissioner; [cited 2018 Jan 5]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm560167.htm

Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, Fizazi K, Bossi A, van den Eertwegh AJM, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184-043): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:700–12.

Cabel L, Loir E, Gravis G, Lavaud P, Massard C, Albiges L, et al. Long-term complete remission with Ipilimumab in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: case report of two patients. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:31.

Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–13.

Graff JN, Alumkal JJ, Drake CG, Thomas GV, Redmond WL, Farhad M, et al. Early evidence of anti-PD-1 activity in enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:52810–7.

de Bono JS, De Giorgi U, Massard C, Bracarda S, Nava Rodrigues D, Kocak I, et al. PTEN loss as a predictive biomarker for the Akt inhibitor ipatasertib combined with abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Ann Oncol [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 16];27. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article/27/suppl_6/718O/2799456

Sumanasuriya S, De Bono J. Treatment of advanced prostate cancer - a review of current therapies and future promise. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med [Internet]. 2017; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a030635

Barbieri CE, Chinnaiyan AM, Lerner SP, Swanton C, Rubin MA. The emergence of precision urologic oncology: a collaborative review on biomarker-driven therapeutics. Eur Urol. 2017;71:237–46.

de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels J-P, Kocak I, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–54.

Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MHA, Lara PN Jr, Jones JA, Taplin ME, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20.

Mailankody S, Prasad V. Five years of cancer drug approvals: innovation, efficacy, and costs. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:539–40.

Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, Luber B, Nakazawa M, Roeser JC, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1028–38.

Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, Wang H, Chen Y, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2149–56.

De Laere B, Oeyen S, Mayrhofer M, Whitington T, van Dam P-J, Van Oyen P, et al. TP53 outperforms other androgen receptor biomarkers to predict abiraterone or enzalutamide outcome in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1943

Steinestel J, Bernemann C, Schrader AJ, Lennerz JK. Re: Emmanuel S. Antonarakis, Changxue Lu, Brandon Luber, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2149-56: AR-V7 Testing: What’s in it for the Patient? Eur Urol. 2017;72:e168–e169.

Scher HI, Graf RP, Schreiber NA, Jayaram A, Winquist E, McLaughlin B, et al. Assessment of the validity of nuclear-localized androgen receptor splice variant 7 in circulating tumor cells as a predictive biomarker for castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1621

Plymate SR, Sharp A, de Bono JS. Nuclear circulating tumor cell androgen receptor variant 7 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: the devil is in the detail. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1615

Spritzer CE, Afonso PD, Vinson EN, Turnbull JD, Morris KK, Foye A, et al. Bone marrow biopsy: RNA isolation with expression profiling in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer--factors affecting diagnostic success. Radiology. 2013;269:816–23.

Ross RW, Halabi S, Ou S-S, Rajeshkumar BR, Woda BA, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Predictors of prostate cancer tissue acquisition by an undirected core bone marrow biopsy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer--a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8109–13.

Lorente D, Omlin A, Zafeiriou Z, Nava-Rodrigues D, Pérez-López R, Pezaro C, et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer tissue acquisition from bone metastases for molecular analyses. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2016;14:485–93.

Holmes MG, Foss E, Joseph G, Foye A, Beckett B, Motamedi D, et al. CT-guided bone biopsies in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: factors predictive of maximum tumor yield. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:1073–81 e1.

Sailer V, Schiffman MH, Kossai M, Cyrta J, Beg S, Sullivan B, et al. Bone biopsy protocol for advanced prostate cancer in the era of precision medicine. Cancer [Internet]. 2017; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31173

Ulz P, Belic J, Graf R, Auer M, Lafer I, Fischereder K, et al. Whole-genome plasma sequencing reveals focal amplifications as a driving force in metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12008.

Romanel A, Gasi Tandefelt D, Conteduca V, Jayaram A, Casiraghi N, Wetterskog D, et al. Plasma AR and abiraterone-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:312re10.

Wyatt AW, Azad AA, Volik SV, Annala M, Beja K, McConeghy B, et al. Genomic alterations in cell-free DNA and enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1598–606.

De Laere B, van Dam P-J, Whitington T, Mayrhofer M, Diaz EH, Van den Eynden G, et al. Comprehensive profiling of the androgen receptor in liquid biopsies from castration-resistant prostate cancer reveals novel intra-AR structural variation and splice variant expression patterns. Eur Urol. 2017;72:192–200.

Wyatt AW, Annala M, Aggarwal R, Beja K, Feng F, Youngren J, et al. Concordance of circulating tumor DNA and matched metastatic tissue biopsy in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2017;109. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx118

Goodall J, Mateo J, Yuan W, Mossop H, Porta N, Miranda S, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA to guide prostate cancer treatment with PARP inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1006–17.

Quigley D, Alumkal JJ, Wyatt AW, Kothari V, Foye A, Lloyd P, et al. Analysis of circulating cell-free DNA identifies multiclonal heterogeneity of BRCA2 reversion mutations associated with resistance to PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:999–1005.

Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, McLellan MD, Johnson KJ, Wendl MC, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20:1472–8.

Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2477–87.

Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, Kishtagari A, Syed A, Jonsson P, et al. Therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non-hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:374–82 e4.

Phallen J, Sausen M, Adleff V, Leal A, Hruban C, White J, et al. Direct detection of early-stage cancers using circulating tumor DNA. Sci Transl Med [Internet]. 2017;9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aan2415

Henao Diaz E, Yachnin J, Grönberg H, Lindberg J. The in vitro stability of circulating tumour DNA. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168153.

De Laere B, Oeyen S, Van Oyen P, Ghysel C, Ampe J, Ost P, et al. Circulating tumor cells and survival in abiraterone- and enzalutamide-treated patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 2018;78:435–45.

Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. p. 2016.

Salipante SJ, Scroggins SM, Hampel HL, Turner EH, Pritchard CC. Microsatellite instability detection by next generation sequencing. Clin Chem. 2014;60:1192–9.

Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153:666–77.

Annala M, Vandekerkhove G, Khalaf D, Taavitsainen S, Beja K, Warner EW, et al. Circulating tumor DNA genomics correlate with resistance to abiraterone and enzalutamide in prostate cancer. Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0937

Na R, Zheng SL, Han M, Yu H, Jiang D, Shah S, et al. Germline mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 distinguish risk for lethal and indolent prostate cancer and are associated with early age at death. Eur Urol. 2017;71:740–7.

Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, De Sarkar N, Abida W, Beltran H, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–53.

Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, Stadler ZK, Joseph V, Zehir A, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing. JAMA. 2017;318:825–35.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–6.

Bozic I, Reiter JG, Allen B, Antal T, Chatterjee K, Shah P, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of cancer in response to targeted combination therapy. Elife. 2013;2:e00747.

Le Tourneau C, Delord J-P, Gonçalves A, Gavoille C, Dubot C, Isambert N, et al. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1324–34.

Heller G, McCormack R, Kheoh T, Molina A, Smith MR, Dreicer R, et al. Circulating tumor cell number as a response measure of prolonged survival for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a comparison with prostate-specific antigen across five randomized phase III clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:572–80.

Mehra N, Dolling D, Sumanasuriya S, Christova R, Pope L, Carreira S, et al. Plasma cell-free DNA concentration and outcomes from taxane therapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer from two phase III trials (FIRSTANA and PROSELICA). Eur Urol. 2018;74:283–91.

Seed G, Yuan W, Mateo J, Carreira S, Bertan C, Lambros M, et al. Gene copy number estimation from targeted next-generation sequencing of prostate cancer biopsies: analytic validation and clinical qualification. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6070–7.

Jiang R, Lu Y-T, Ho H, Li B, Chen J-F, Lin M, et al. A comparison of isolated circulating tumor cells and tissue biopsies using whole-genome sequencing in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:44781–93.

Lohr JG, Adalsteinsson VA, Cibulskis K, Choudhury AD, Rosenberg M, Cruz-Gordillo P, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of circulating tumor cells provides a window into metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:479–84.

FoundationACT [Internet]. Foundation Medicine. [cited 2018 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.foundationmedicine.com/genomic-testing/foundation-act

Personal Genome Diagnostics | Pharma-Biotech Liquid Biopsy [Internet]. Personal Genome Diagnostics. [cited 2018 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.personalgenome.com/pharma-biotech-companies/liquid-biopsy/

Guardant360 | Guardant Health [Internet]. Guardant Health. [cited 2018 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.guardanthealth.com/guardant360/

Torga G, Pienta KJ. Patient-paired sample congruence between 2 commercial liquid biopsy tests. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2017; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4027

Jones S, Anagnostou V, Lytle K, Parpart-Li S, Nesselbush M, Riley DR, et al. Personalized genomic analyses for cancer mutation discovery and interpretation. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:283ra53.

Hu Y, Ulrich BC, Supplee J, Kuang Y, Lizotte PH, Feeney NB, et al. False-positive plasma genotyping due to clonal hematopoiesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:4437–43.

European Commission. FAQ - Research Participant Portal [Internet]. [cited 2018 Aug 9]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/portal/desktop/en/support/faqs/faq-2890.html

de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, Parker C, Miller MC, Tissing H, et al. Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6302–9.

Peeters DJE, De Laere B, Van den Eynden GG, Van Laere SJ, Rothé F, Ignatiadis M, et al. Semiautomated isolation and molecular characterisation of single or highly purified tumour cells from CellSearch enriched blood samples using dielectrophoretic cell sorting. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1358–67.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients for their willingness to participate in this study. We thank Luc De Laere, Thijs Develter, Sophie Vantieghem, Sofie Herman, Gwen Colfs, Veerle Lamotte, Anita Boumans, Abdelbari Baitar, Roos Haeck, Goele Wallays, Hanna Emanuelsson, Per Gustafsson, Jenny Wängberg, Maria Bergh, and Claudia Maes for their assistance with patient inclusion, sampling management, and data collection. We also thank Rebecka Bergström for excellent bioinformatic support.

Funding

The Belgian Foundation Against Cancer (grant number C/2014/227); Kom op tegen Kanker (Stand up to Cancer), the Flemish Cancer Society (grant number 00000000116000000206); Royal College of Surgeons/Cancer Research UK (C19198/A1533); The Cancer Research Funds of Radiumhemmet, through the PCM program at KI (grant number 163012); The Erling-Persson family foundation (grant number 4-2689-2016); the Swedish Research Council (grant number K2010-70X-20430-04-3), and the Swedish Cancer Foundation (grant number 09-0677). These funding bodies had no role in the design, execution, or interpretation of the data in this study and did not influence the decision to submit results for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant for the interpretation of our findings is provided in the main manuscript or the supplemental information except for the raw sequence data. Any data providing genotype information is considered to be a personal registry by the Swedish law (Personal Data Act), thereby prohibiting the submission to a public repository. The raw sequence data is instead available upon request from the authors (contact johan.lindberg@ki.se) if approval has been obtained from the Regional Ethical Vetting Board in Stockholm.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BDL, PR, JL, and HG conceived the study and designed the methodologies and experiments. BDL, SO, JL, and GVdE performed experiments and acquired data. BDL, MM, TW, JL, and MR analysed and interpreted the data. PVO, CG, JA, PO, WD, LH, DS, BB, WL, EE, DDM, MS, KF, AR, AU, JY, HG, TN, MA, PR, and LD recruited patients and acquired blood samples for analysis. BDL, PR, JL, MM, and HG prepared the manuscript. BDL, PR, SO, MM, LE, TW, PJvD, PVO, CG, JA, PO, WD, LH, DS, BB, WL, EE, DDM, MS, KF, AB, DG, LH, GVdE, AR, MR, AU, JY, HG, SVL, JL, and LD performed critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from ethical committees in Belgium (Antwerp University Hospital, registration number: B300201524217) and Sweden (Stockholm Regional Ethical Vetting Board registration numbers: 2016/101-32, amendment 2017/252-32; 2009/780-31/4, amendment 2014/1564-32). All patients provided a written informed consent document. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

All patients additionally consented to have their data published in an anonymous format. Each patient and blood draw were assigned an untraceable number. The sample donor ID represents a unique patient and the sample ID a specific sampling occasion.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Supplemental methods. (DOCX 21 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Detailed overview of the capture designs and targeted regions. (XLSX 974 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Summary of bioinformatic tools and settings. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S3. Overview of which samples that were sequenced with which capture design. (XLSX 123 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S4. Overview of the number of samples per described analysis. (XLSX 12 kb)

Additional file 6:

Figure S1. Circulating tumor DNA fraction in baseline samples. Figure S2. Tumor burden at different lines of therapy. Figure S3. Correlation between circulating tumor cell count and circulating tumor DNA fraction. Figure S4. Microsatellite instability by targeted sequencing of microsatellites. Figure S5. Chained structural event. Figure S6. Gene body panel design. Figure S7. Subclonal dynamics. Figure S8. Correlation between circulating tumor DNA fraction and cell-free DNA concentration. Figure S9. Baseline circulating tumor DNA fraction and circulating tumor cell counts at first- and second-line mCRPC treatment [68, 69]. Figure S10. False positive rate evaluation for point mutation variant calling. Figure S11. Allele frequencies of structural variants and mutations. (DOCX 3335 kb)

Additional file 7:

Table S5. CTC count, ctDNA fraction and line of therapy. (XLSX 27 kb)

Additional file 8:

Table S6. Somatic and germline alterations. (XLSX 141 kb)

Additional file 9:

Table S7. Table comparing relevant germline alterations, presented here, with other publications. (XLSX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mayrhofer, M., De Laere, B., Whitington, T. et al. Cell-free DNA profiling of metastatic prostate cancer reveals microsatellite instability, structural rearrangements and clonal hematopoiesis. Genome Med 10, 85 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-018-0595-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-018-0595-5