Abstract

Background

Salinity, exacerbated by rising sea levels, is a critical environmental cue affecting freshwater ecosystems. Predicting ecosystem structure in response to such changes and their implications for the geographical distribution of arthropod disease vectors requires further insights into the plasticity and adaptability of lower trophic level species in freshwater systems. Our study investigated whether populations of the mosquito Culex pipiens, typically considered sensitive to salt, have adapted due to gradual exposure.

Methods

Mesocosm experiments were conducted to evaluate responses in life history traits to increasing levels of salinity in three populations along a gradient perpendicular to the North Sea coast. Salt concentrations up to the brackish–marine transition zone (8 g/l chloride) were used, upon which no survival was expected. To determine how this process affects oviposition, a colonization experiment was performed by exposing the coastal population to the same concentrations.

Results

While concentrations up to the currently described median lethal dose (LD50) (4 g/l) were surprisingly favored during egg laying, even the treatment with the highest salt concentration was incidentally colonized. Differences in development rates among populations were observed, but the influence of salinity was evident only at 4 g/l and higher, resulting in only a 1-day delay. Mortality rates were lower than expected, reaching only 20% for coastal and inland populations and 41% for the intermediate population at the highest salinity. Sex ratios remained unaffected across the tested range.

Conclusions

The high tolerance to salinity for all key life history parameters across populations suggests that Cx. pipiens is unlikely to shift its distribution in the foreseeable future, with potential implications for the disease risk of associated pathogens.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salinization of fresh water in coastal areas, especially in low-lying deltas, is a natural process that is currently exacerbated by anthropogenic drivers, such as climate change-induced sea level rise, land subsidence, and saline groundwater seepage, intensified by the removal of overlying fresh water [1]. Saltwater infiltration is commonly acknowledged to negatively affect agricultural yield and freshwater ecosystem services [2]. The underlying physical processes of salinization are relatively well described [3, 4], and animal diversity at large is understood to decrease under transitory conditions [5]. However, little is known about the direct and indirect effects of salinization on animal populations inhabiting (currently freshwater) ecosystems in deltas, especially for species that are disease vectors.

The cosmopolitan house mosquito Culex pipiens species complex is a known vector for a variety of pathogens, including West Nile virus, Usutu, and avian malaria [6,7,8,9]. It has a wide habitat tolerance, ranging from clean rainwater-filled containers to strongly polluted temporal water bodies, such as ground puddles, and even manure tanks [10, 11]. Similar to other mosquito larvae typically associated with fresh water, it accumulates organic osmolytes to combat ionic pressure instead of active ion transport [12] and is known to be quite vulnerable to changes in salinization relative to other mosquito species [13,14,15], with a median lethal dose (LD50) of 4 g/l and a lethal dose (LD100) of 6–10 g/l chloride for acute salinity stress [15,16,17].

Although a variety of responses to salinization exist among invertebrates [12], general trends exist in the whole invertebrate community. Salinization has been shown to shape insect community structures, negatively affecting diversity [18, 19] via decreased food availability [20, 21]. Although mosquitoes have previously been described to react quite similarly [5, 22], it has also been hypothesized that their short generation time (when compared to that of many other macrofauna species, including their predators [23]) might enable mosquitoes to adapt more rapidly [24,25,26]. This could subsequently cause a relative increase in population size in transitory systems due to the alleviation of predation pressure and the relative increase in food resources [19]. Such a fast adaptation rate is observed for a variety of other stressors, such as pesticides [27,28,29]. These adaptations are similar to the response to salinization, i.e., by affecting the excretion of harmful compounds [12, 30]. This renders it likely that mosquitoes are better able to adapt to increasing salinity than other insect species.

Salinization affects mosquito habitat quality and may thus reduce larval survival. However, this depends on how well the larvae are adapted to temporary (i.e., flooding) and continuous salinization events and processes, causing species-specific effects [15]. These adaptations in osmoregulation include physiological (reduced surface area of anal papillae or active transport of ions) [31, 31, 32] and behavioral adaptations (increased metabolism and uptake of organic compounds in hemolymph) [32,33,34,35,36,37], resulting in tolerance that changes across life stages [38] and differs between sexes [39]. Namely, female mosquitoes tend to be less strongly selected for early maturation, which may lead to prolonged exposure to stress as compared to males [40]. With time, adaptation to salinization has caused species-specific preferences during oviposition [40,41,42,43], further shaping mosquito community composition.

At the population level, commonly considered intolerant species such as Cx. pipiens sensu lato (s.l.) might be affected by salinization in a variety of ways. Salinization might cause (i) no change when tolerance via for instance plastic behavior proves sufficient, (ii) local extinction of the species if tolerance is insufficient, (iii) displacement when unfavorable conditions are perceived during ovipositing, or (iv) local adaptation leading to possibly increased tolerance due to gradual, continuous exposure.

This study aimed to evaluate whether (local) adaptation to salinization occurred, by quantifying and comparing the tolerance of Cx. pipiens populations along a gradient from coast to inland. We expected increasing levels of adaptation (i.e., lower mortality, more rapid development, and a balanced sex ratio) closer to the coast as a result of gradual exposure. To this end, we performed a mesocosm experiment. We varied concentrations from 0 to 8 g of chloride per liter with intervals of 2 g, i.e., from fresh water to the predicted maximum inland surface water concentration of 7.5 g/l Cl− [44], or the brackish-marine transition zone [45], at almost half the concentration of seawater.

Methods

Collection and rearing of experimental populations

Culex pipiens egg rafts were collected during the 2 days prior to the start of an experimental round from one set of naturally colonized black plastic mesocosms in peri-urban areas of the cities of Leiden, Utrecht, and Nijmegen, representing coastal (7 km to sea), intermediate (43 km to sea), and inland (108 km to sea) mosquito populations, respectively. All populations were collected at similar altitudes (2–5 m above sea level [asl]). For this purpose, the mesocosms were filled with 6 l of hypertrophic water (100 mg N-total), after which they were placed under tree cover. The larvae were subsequently allowed to hatch in 50 ml Falcon tubes, where they were kept at ambient temperature until the start of the experiment. Previous pilot studies have indicated that this type of experiment attracts Cx. pipiens and Culiseta annulata only [40, 46]. The collected egg rafts were distinguished from those of Cs. annulata by their difference in size [47, 48].

Experimental setup

The setup consisted of 45 white plastic 12 l mesocosms, each with a 200 W aquarium heater. The experiments were conducted under standardized outdoor conditions [40] at the Hortus botanicus, Leiden, the Netherlands. The aquarium heaters were programmed at a minimum temperature of 20 °C for optimal development, while allowing for natural fluctuations, so that the development was representative of field conditions during the peak of the Dutch mosquito season [40, 49, 50]. Namely, as increased temperature heightens metabolism, ion uptake and transport may be increased, making it imperative to work under such conditions.

All 45 mesocosms were filled with 8 l of dechlorinated tap water (maintained at a constant level during the experiments), a natural concentration of microbes, a high concentration of nutrients, and a specific concentration of sea salt (Jozo, Rotterdam, the Netherlands). For the natural concentration of microbes, 1 l of water from a local lake was filtered per liter of tap water using a 250 μm plankton net and 53 μm collector. The high concentration of nitrogen prevents food from being a limiting factor and thus minimizes cannibalism (Koenraadt and Takken, 2003). This was achieved by adding 20 mg/l N in the form of dry cow manure (2.4% N, 1.5% P2O5, and 3.1% K2O) to the water. The mesocosms were randomly allocated to five increasing concentrations of commercially available sea salt—0 g/l, 2 g/l, 4 g/l, 6 g/l, and 8 g/l Cl—and split into two rounds of experiments due to spatial constraints, which are described below. The treatments were representative of fresh water [51], the highest measured salinity in a Dutch ditch [52], the LD50 [15], the highest measured salinity in seepage water [52], and the highest reported LD100 for Cx. pipiens [15], respectively (Table 1). In the first round, 0 g/l, 2 g/l, and 6 g/l Cl− were used, and in the second round, 0 g/l, 4 g/l, and 8 g/l Cl− were used.

For each concentration, a mixture of water, microbes, nutrients, and sea salt was prepared [40, 46], and salt was added over the course of 4 days in equal parts to limit osmotic stress to the microbial community. The mixture was thereafter covered with fine mesh (0.1 mm) to prevent additional colonization and was subsequently left to acclimatize for a period of 2 weeks. After the acclimation period, the water was divided over the experimental mesocosms using a 500 μm sieve to filter out any detritus and macroinvertebrates. After filtering, 100 second-instar larvae were added, and the aquarium heaters were turned on. Allocation of the populations and saline concentrations was performed in a Latin square, leading to five replicates for each population–concentration combination. During the experiment, the mesocosms were once again closed off using mesh to prevent predation and colonization from the outside and to ensure that the emerged mosquitoes could not escape. Temperature, chlorophyll a concentration, turbidity, and conductivity were measured as potential covariates using a Hach HQ40d multi-parameter meter and Turner Designs AquaFluor. Before the second round of the experiment, the original mixtures were collected, and the concentrations were increased from 2 g/l to 4 g/l and from 6 g/l to 8 g/l. The mixtures were once again left to acclimatize and were subsequently allocated to a new Latin square.

Measurements of population parameters

Larval development was measured 5 days a week. First, the water was stirred clockwise once with a 400 mm-wide Φ 200 μm sieve to create a circular water flow and prevent the larvae from diving. The sieve was subsequently used to collect the larvae by fully submerging the sieve and moving it counterclockwise twice. All collected larvae were morphologically characterized to developmental stage using the size of the head capsule as a morphological indicator [53]. The identifications were compared daily with a previously reared reference collection of Cx. pipiens developmental stages. The procedure was repeated up to five times until at least 20 larvae were sampled.

Pupae were collected daily, after which they were allowed to emerge in 50 ml Falcon tubes. Sex was determined based on characteristics including plumose/pilose antennae and the length of the palps [53]. The proportion of total survival was determined by dividing the number of emerged adults by the original density of 100 larvae. The proportion of survival, used for visualization, was calculated by subtracting the mean of the control per population from the absolute survival rate. The time to pupation was determined after completion of the experiment. Time to pupation was defined as the interval between the start of the experiment and the first day upon which at least 50% of the subsampled larvae had turned/developed into pupae. The median time to emergence was determined by calculating the interval between the start of the experiment and the capture of 50% of the emerged adults. When no more pupae or adult mosquitoes were found for two subsequent days in a mesocosm, it was assumed that no living mosquitoes remained, and the mesocosm was closed off.

Ovipositioning behavior

The ovipositioning behavior of the coastal population was determined in a separate experiment at the Hortus botanicus Leiden, the Netherlands. Five clusters—each consisting of one black, plastic 8 l bucket for each of the five salt concentrations—were placed around the botanical gardens at a distance of at least 58 m from each other to prevent the clusters from interfering with each other. The water, microbial community, and salinity levels were prepared as described in the previous section. Ovipositioning behavior was recorded by daily counts of egg rafts per mesocosm for a total of 12 days. Encountered egg rafts were removed to minimize the positive feedback caused by their presence [54].

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed in R version 4.2.2 [55]. Variance across experimental rounds was normalized based on the observed variance across the experimental rounds per population per salinity. Log–logistic regression was used to determine the LD50 and LD100 using the drc package [56]. Linear mixed-effects models were used to test for (normalized) differences in survival, development time (to pupation and emergence), and sex ratio across the different salinity levels. The salinity level, population, experimental round, average turbidity, conductivity, and chlorophyll a concentration were included as covariates. The individual mesocosms were included as random effect. The effect on ovipositioning behavior was similarly explored; a linear mixed model was applied using salinity level as main effects and day and location as random variables. All models (Additional file 1: Table S1) were optimized by the Akaike information criterion using stepwise regression with backward elimination. Dependent variables were tested for normality and assessed using quantile–quantile plots and Levene's test (P = 0.05).

Results

Effect of salinity on total proportion of survival

The total proportion of survival decreased with increasing salinity for all populations (F(4,85) = 5.60, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.281), with 18%, 42%, and 20% (p < 0.001, P = 0.005, and p = 0.001 for coastal, intermediate, and inland, respectively; Fig. 1) from 4 g/l onward (Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2). Differences in slope were detected between the coastal and intermediate populations (t(30,27) = −2.51, P adj < 0.001), coastal and inland populations (t(30,28) = −3.83, adj = 0.031), but not between the intermediate and inland populations (t(28,27) = 0.69, P adj > 0.05).

Proportion of normalized total survival per population across increasing salinization levels as a boxplot with outliers as dots and b dose–response curve with standard error. Total survival is depicted as the number of emerged adults at the end of the experiment as a fraction of the initial number of larvae

Effect of salinity on development rates

A minor increase in the time to pupation (Additional file 1: Fig. S1) and time to emergence (Fig. 2) was detected with increasing salinity. Development to emergence was equally slowed for all populations. On average, larvae exposed to 8 g/l NaCl took 1 day longer to emerge than those exposed to 0 g/l NaCl (t(4,71) = −2.849, p < 0.041, partial η2 = 0.412; Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S3).

Effect of salinity on sex ratio

A minor difference in sex ratio was detected with increasing salinity or among any of the populations (F(2,62) = 3.266, p = 0.045, partial η2 = 0.102; Fig. 3; Additional file 1: Table S4), between the coastal and inland populations (P adj = 0.013).

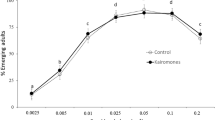

Effect of salinity on ovipositioning behavior

Oviposition decreased with increasing salt concentration (F(4297) = 25.863, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.273; Fig. 3; Table 2; Additional file 1: Table S5). The average oviposition rate decreased by 67% to 1.5 rafts or approximately 300 eggs [53] at 2 g/l and subsequently by 11% to one raft or approximately 200 eggs at 4 g/l. Oviposition rates at 6 g/l were almost negligible, at 9% (Additional file 1).

Discussion

Contrary to our expectations, our results suggest that the investigated populations of Cx pipiens are highly tolerant to salinization, irrespective of their proximity to the current coastline. At the highest salinity (Fig. 1), representative of almost half the concentration of seawater, more than half of the larvae survived for all tested populations, instead of the expected 0% [15,16,17]. Differences in development rates among populations were observed, but the influence of salinity was evident only at 4 g/l or higher, resulting in a minor delay (Fig. 2). The sex ratios remained unaffected across the tested range, indicating no expected effect on potential population growth (Fig. 3). Our data additionally suggest that, although concentrations up to the previously described LD50 (4 g/l) were favored during egg laying, Cx. pipiens readily lays eggs under conditions of up to 6 g/l Cl− and, incidentally, under 8 g/l Cl−. This finding is in line with observational data, as Cx. pipiens has recently been repeatedly observed to inhabit Dutch salt marches (pers. comm. J.G. van der Beek), which suggests a more congruent link between ovipositioning behavior and larval survival than has been described for other species [42, 57, 58].

Our observations are striking in contrast to the previously described LD100 of 6–7 g/l Cl− in the USA and France [15,16,17]. There are several methodological differences between the current study and previous literature: (i) the use of second-instar larvae, which might increase the potential for physiological changes in response to saline conditions [34] relative to the use of older larvae; (ii) the use of eutrophic conditions, which, by increasing the energy budget of the larvae, might allow for higher metabolic rates, increasing the ability to expel the ionic waste [35]; and, finally, (iii) gradual acclimation of the locally sourced microbial community, which might have allowed for a higher microbial abundance and thus food availability during the experiment. The latter might have allowed for increased uptake of organic compounds, which may reduce the effects of the water’s osmolality [36]. While the relevance of each of these differences in setup cannot be distinguished with the current setup, the difference in total survival between our study and the earlier findings is far greater than might be explained by changes in methodology.

As our experimental setting is more representative of field conditions, the currently described responses might be more ecologically relevant than those described in previous studies under controlled conditions in the laboratory, as these generally use alternate food sources (e.g., fish feed), tap water without a natural microbial community [59], or laboratory-reared communities of a laboratory colony with a single subspecies. Given the ecological relevance of the setup applied, the observed pattern might be representative of populations in the Netherlands and possibly even for many other low-lying deltas. Based on these results, we speculate that similar patterns may exist for other mosquito species that inhabit lowland delta areas, such as Culiseta morsitans, Culex modestus, and perhaps even Aedes aegypti, which would imply that the current LD50 and LD100 should be reassessed. Taken together, the difference in the responses of our study and laboratory studies suggests that, while a wide range of mosquito species are typically associated with freshwater systems [60], they may exhibit substantial plasticity and/or (local) adaptation to increasing salinization.

Conclusions

The current results suggest that coastal house mosquito populations will persist and will not show salinity-induced inland dispersal or local reductions in survival. The ecological implications are that they may instead locally increase in population size, despite the presence of predators. Many freshwater predator groups, including dragonflies and damselflies [61] and mayflies and true bugs [62], have longer generation times and may be vulnerable to salinization within the range tested. However, this assumption remains to be tested. Species diversity in transitory systems tends to decrease between freshwater and saline water [5, 18], while total insect abundance may remain unchanged [19]. Consequently, species that are able to persist in such systems may experience alleviation of predation pressure, causing population sizes to increase over time and increasing nuisance and disease risk. However, additional information is needed, as many studies on the tolerance of predator species are prone to methodological limitations similar to those of prior work on mosquitoes themselves. Nevertheless, house mosquito nuisance in coastal areas is likely to persist during the foreseeable future, and our results suggest that it is not unlikely that other mosquito species in coastal areas are similarly able to adapt to increasing salt levels even though their predators cannot.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its appendices. The original datasets used and analyzed during the present study are freely and openly available within the appendices. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files 2, 3.

References

van Baaren E, Oude Essink GHP. Verzilting van het Nederlandse grondwatersysteem. The Netherlands: Deltares; 2009. Report No.: 0903–0026. https://publications.deltares.nl/0903-0026.pdf.

Bonte M, Zwolsman JJG. Climate change induced salinisation of artificial lakes in the Netherlands and consequences for drinking water production. Water Res. 2010;44:4411–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2010.06.004.

Khan AE, Ireson A, Kovats S, Mojumder SK, Khusru A, Rahman A, et al. Drinking water salinity and maternal health in coastal Bangladesh: implications of climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1328–32. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002804.

Lassiter A. Rising seas, changing salt lines, and drinking water salinization. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2021;50:208–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.04.009.

Telesh I, Schubert H, Skarlato S. Life in the salinity gradient: discovering mechanisms behind a new biodiversity pattern. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2013;135:317–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2013.10.013.

Bravo-Barriga D, Parreira R, Almeida APG, Calado M, Blanco-Ciudad J, Serrano-Aguilera FJ, et al. Culex pipiens as a potential vector for transmission of Dirofilaria immitis and other unclassified Filarioidea in Southwest Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2016;223:173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.04.030.

Gutiérrez-López R, Martínez-de la Puente J, Gangoso L, Yan J, Soriguer RC, Figuerola J. Do mosquitoes transmit the avian malaria-like parasite Haemoproteus? An experimental test of vector competence using mosquito saliva. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:609.

Hubálek Z. Mosquito-borne viruses in Europe. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-008-1064-7.

Kazlauskienė R, Bernotienė R, Palinauskas V, Iezhova TA, Valkiūnas G. Plasmodium relictum (lineages pSGS1 and pGRW11): Complete synchronous sporogony in mosquitoes Culex pipiens pipiens. Exp Parasitol. 2013;133:454–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2013.01.008.

Becker N, Dahl C, Bryant B, Blair CD, Olson KE, Clem RJ, et al. Mosquitoes and their control. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92874-4.

Rejmánková E, Grieco J, Achee N, Roberts DR. Ecology of larval habitats. In: Manguin S, editor. Anopheles mosquitoes new insights malar vectors. Sevastopolskaya: InTech; 2013.

Chown SL, Nicolson S. Insect physiological ecology: mechanisms and patterns. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Abou-Attia FA, El-Khodary AS, Metwally SMI, Hassan HM. Monthly fluctuations of larval and pupal densities of Culex pipiens (L.) with special reference to the effect of aquatic physiochemical properties on their habitats at kafr el-sheikh region. J Plant Prot Pathol. 2000;25:2377–86. https://doi.org/10.1608/jppp.2000.258838.

Kenawy MA, Ammar SE, Abdel-Rahman HA. Physico-chemical characteristics of the mosquito breeding water in two urban areas of Cairo Governorate. Egypt J Entomol Acarol Res. 2013;45:17. https://doi.org/10.4081/jear.2013.e17.

Kengne P, Charmantier G, Blondeau-Bidet E, Costantini C, Ayala D. Tolerance of disease-vector mosquitoes to brackish water and their osmoregulatory ability. Ecosphere. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2783.

Brown BJ, Platzer EG. Salts and the infectivity of Romanomermis culicivorax. J Nematol. 1978;10:53.

Chidester FE. The influence of salinity on the development of certain species of mosquito larvae and its bearing on the problem of the distribution of species. Bull N J Agric Exp Stn. 1916.

Bleich S, Powilleit M, Seifert T, Graf G. β-diversity as a measure of species turnover along the salinity gradient in the Baltic Sea, and its consistency with the Venice system. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2011;436:101–18. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09219.

Silberbush A, Blaustein L, Margalith Y. Influence of salinity concentration on aquatic insect community structure: a mesocosm experiment in the Dead Sea basin region. Hydrobiologia. 2005;548:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-004-8336-8.

van Dijk G, Lamers LPM, Loeb R, Westendorp P-J, Kuiperij R, van Kleef HH, et al. Salinization lowers nutrient availability in formerly brackish freshwater wetlands; unexpected results from a long-term field experiment. Biogeochemistry. 2019;143:67–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-019-00549-6.

Ersoy Z, Abril M, Cañedo-Argüelles M, Espinosa C, Vendrell-Puigmitja L, Proia L. Experimental assessment of salinization effects on freshwater zooplankton communities and their trophic interactions under eutrophic conditions. Environ Pollut. 2022;313:120127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120127.

Balasubramanian R, Sahina S, Nadh VA, Sreelekha KP, Nikhil TL. Effects of different salinity levels on larval growth and development of disease vectors of Culex species. J Environ Biol. 2019;40:1115–22. https://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/40/5/MRN-950.

Verberk WCEP, Siepel H, Esselink H. Life-history strategies in freshwater macroinvertebrates. Freshw Biol. 2008;53:1722–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.02035.x.

Carlson SM, Cunningham CJ, Westley PAH. Evolutionary rescue in a changing world. Trends Ecol Evol. 2014;29:521–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.06.005.

Martin AP, Palumbi SR. Body size, metabolic rate, generation time, and the molecular clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:4087–91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.90.9.4087.

Thomas JA, Welch JJ, Lanfear R, Bromham L. A generation time effect on the rate of molecular evolution in invertebrates. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1173–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msq009.

Hamdan H, Sofian-Azirun M, Ahmad NW, Lim LH. Insecticide resistance development in Culex quinquefasciatus (Say), Aedes aegypti (L) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) larvae against malathion, permethrin and temephos. Trop Biomed. 2005;22:45–52.

Nazni W, Lee H, Azahari A. Adult and larval insecticide susceptibility status of Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) mosquitoes in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2005;22:63–8.

Ser O, Cetin H. Investigation of susceptibility levels of Culex pipiens L (Diptera: Culicidae) populations to synthetic pyrethroids in Antalya province of Turkey. J Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2019;13:243–58.

Asakura K. The anal portion as a salt-excreting organ in a seawater mosquito larva, Aedes togoi Theobald. J Comp Physiol B. 1980;138:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00688736.

Akhter H, Misyura L, Bui P, Donini A. Salinity responsive aquaporins in the anal papillae of the larval mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2017;203:144–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.09.008.

Donini A, Gaidhu MP, Strasberg DR, O’Donnell MJ. Changing salinity induces alterations in hemolymph ion concentrations and Na+ and Cl– transport kinetics of the anal papillae in the larval mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:983–92. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.02732.

Aly C, Dadd RH. Drinking rate regulation in some fresh-water mosquito larvae. Physiol Entomol. 1989;14:241–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3032.1989.tb01090.x.

Bradley TJ. Physiology of osmoregulation in mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1987;32:439–62. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.002255.

Bradley TJ, Phillips JE. The effect of external salinity on drinking rate and rectal secretion in the larvae of the saline-water mosquito. J Experim Bio. 1976. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.66.1.97.

De Brito AM, Mucci LF, Serpa LLN, De Moura RM. Effect of salinity on the behavior of Aedes aegypti populations from the coast and plateau of southeastern Brazil. J Vector Borne Dis. 2015;52:79–87.

Patrick ML, Bradley TJ. Regulation of compatible solute accumulation in larvae of the mosquito Culex tarsalis: osmolarity versus salinity. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:831–9. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.203.4.831.

Mottram P, Kay BH, Fanning ID. Development and survival of Culex sitiens Wiedemann (Diptera: Culicidae) in relation to temperature and salinity. Aust J Entomol. 1994;33:81–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-6055.1994.tb00926.x.

Alcalay Y, Puzhevsky D, Tsurim I, Scharf I, Ovadia O. Interactive and sex-specific life-history responses of Culex pipiens mosquito larvae to multiple environmental factors. J Zool. 2018;306:268–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.12611.

Boerlijst SP, Johnston ES, Ummels A, Krol L, Boelee E, van Bodegom PM, et al. Biting the hand that feeds: anthropogenic drivers interactively make mosquitoes thrive. Sci Total Environ. 2023;858:159716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159716.

Navarro DMAF, de Oliveira PES, Potting RPJ, Brito AC, Fital SJF, Sant’Ana AEG. The potential attractant or repellent effects of different water types on oviposition in Aedes aegypti L (Dipt, Culicidae). J Appl Entomol. 2003;127:46–50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0418.2003.00690.x.

Roberts DM, Irving-Bell RJ. Salinity and microhabitat preferences in mosquito larvae from southern Oman. J Arid Environ. 1997;37:497–504. https://doi.org/10.1006/jare.1997.0291.

Silberbush A, Tsurim I, Margalith Y, Blaustein L. Interactive effects of salinity and a predator on mosquito oviposition and larval performance. Oecologia. 2014;175:565–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-014-2930-x.

Delsman J, Oude Essink G, Huizer S, Bootsma H, Mulder T, Zitman P, et al. Actualisatie zout in het NHI. Deltares; 2020. Report No.: 11205261–003-BGS-0001.

Dahl E. Ecological salinity boundaries in poikilohaline waters. Oikos. 1956;7:1. https://doi.org/10.2307/3564981.

Dellar M, Boerlijst SP, Holmes D. Improving estimations of life history parameters of small animals in mesocosm experiments: a case study on mosquitoes. Methods Ecol Evol. 2022;13:1148–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13814.

Chapman GE, Sherlock K, Hesson JC, Blagrove MSC, Lycett GJ, Archer D, et al. Laboratory transmission potential of British mosquitoes for equine arboviruses. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:413. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04285-x.

Sames WJ, Schleichi SS, Johnson OD. Egg raft size and bionomical notes on Culiseta incidens theobald in western Washington. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21:469–71. https://doi.org/10.2987/8756-971X(2006)21[469:ERSABN]2.0.CO;2.

Beck-Johnson LM, Nelson WA, Paaijmans KP, Read AF, Thomas MB, Bjørnstad ON. The importance of temperature fluctuations in understanding mosquito population dynamics and malaria risk. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:160969. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160969.

De Majo MS, Zanotti G, Campos RE, Fischer S. Effects of constant and fluctuating low temperatures on the development of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from a temperate region. J Med Entomol. 2019;56:1661–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjz087.

Oude Essink GHP, van Baaren ES, de Louw PGB. Effects of climate change on coastal groundwater systems: a modeling study in the Netherlands. Water Resour Res. 2010;46:10. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009WR008719.

Geest GJ, Arts GHP, van Dijk G. Systeemkennis brakke wateren. Wageningen: Wageningen University; 2022.

Becker N, Petric D, Zgomba M, Boase C, Madon M, Dahl C, et al. Mosquitoes and their control. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92874-4.

Bruno DW, Laurence BR. The influence of the apical droplet of Culex egg rafts on oviposition of Culex pipiens faticans (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1979;16:300–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/16.4.300.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018.

Ritz C, Baty F, Streibig JC, Gerhard D. Dose-response analysis using R. PLoS ONE. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146021.

Yee DA, Glasgow WC, Ezeakacha NF. Quantifying species traits related to oviposition behavior and offspring survival in two important disease vectors. PLoS ONE. 2020;16:e0250288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239636.

Roberts D. Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) breeding in brackish water: female ovipositional preferences or larval survival? J Med Entomol. 1996;33:525–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/33.4.525.

Kauffman E, Payne A, Franke M, Schmid M, Harris E, Kramer L. Rearing of Culex spp. and Aedes spp. mosquitoes. BIO-Protoc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.2542.

Multini LC, Oliveira-Christe R, Medeiros-Sousa AR, Evangelista E, Barrio-Nuevo KM, Mucci LF, et al. The influence of the pH and salinity of water in breeding sites on the occurrence and community composition of immature mosquitoes in the green belt of the city of São Paulo. Brazil Insects. 2021;12:797. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12090797.

Golovatyuk LV, Shitikov VK. Salinity tolerance of macrozoobenthic taxa in small rivers of the Lake Elton basin. Russ J Ecol. 2016;47:540–5. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1067413616060059.

Dunlop JE, Horrigan N, McGregor G, Kefford BJ, Choy S, Prasad R. Effect of spatial variation on salinity tolerance of macroinvertebrates in Eastern Australia and implications for ecosystem protection trigger values. Environ Pollut. 2008;151:621–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.03.020.

Acknowledgements

Gertjan Geerling is gratefully acknowledged for his help in the collection of egg rafts. We thank Hortus botanicus Leiden for allowing us to conduct our experiments on their premises. We thank Toos van Peuzelen for their helpful discussions and support during the conceptualization and collection of the data.

Funding

This publication is part of the project “Preparing for vector-borne virus outbreaks in a changing world: a One Health Approach” (NWA.1160.1S.210), which is (partly) financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB and MS conceived the general idea for the experiments. SB set up the experiments, and AG and LA carried out the measurements. SB performed interpretation together with EB, RB, PB and MS. SB carried out all statistical analyses, together with PB and MS. All the authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Electronic appendix.

Additional file 2.

Original data.

Additional file 3.

Script for statistical analyses.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boerlijst, S.P., van der Gaast, A., Adema, L.M.W. et al. Taking it with a grain of salt: tolerance to increasing salinization in Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) across a low-lying delta. Parasites Vectors 17, 251 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06268-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06268-8