Abstract

Background

Malaria remains one of the most important infectious diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, responsible for approximately 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths in 2020. In this region, malaria transmission is driven mainly by mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae and, more recently, Anopheles funestus complex. The gains made in malaria control are threatened by insecticide resistance and behavioural plasticity among these vectors. This, therefore, calls for the development of alternative approaches such as malaria transmission-blocking vaccines or gene drive systems. The thioester-containing protein 1 (TEP1) gene, which mediates the killing of Plasmodium falciparum in the mosquito midgut, has recently been identified as a promising target for gene drive systems. Here we investigated the frequency and distribution of TEP1 alleles in wild-caught malaria vectors on the Kenyan coast.

Methods

Mosquitoes were collected using CDC light traps both indoors and outdoors from 20 houses in Garithe village, along the Kenyan coast. The mosquitoes were dissected, and the different parts were used to determine their species, blood meal source, and sporozoite status. The data were analysed and visualised using the R (v 4.0.1) and STATA (v 17.0).

Results

A total of 18,802 mosquitoes were collected, consisting of 77.8% (n = 14,631) Culex spp., 21.4% (n = 4026) An. gambiae sensu lato, 0.4% (n = 67) An. funestus, and 0.4% (n = 78) other Anopheles (An. coustani, An. pharoensis, and An. pretoriensis). Mosquitoes collected were predominantly exophilic, with the outdoor catches being higher across all the species: Culex spp. 93% (IRR = 11.6, 95% Cl [5.9–22.9] P < 0.001), An. gambiae s.l. 92% (IRR = 7.2, 95% Cl [3.6–14.5]; P < 0.001), An. funestus 91% (IRR = 10.3, 95% Cl [3.3–32.3]; P < 0.001). A subset of randomly selected An. gambiae s.l. (n = 518) was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), among which 77.2% were An. merus, 22% were An. arabiensis, and the rest were not identified. We were also keen on identifying and describing the TEP1 genotypes of these mosquitoes, especially the *R3/R3 allele that was identified recently in the study area. We identified the following genotypes among An. merus: *R2/R2, *R3/R3, *R3/S2, *S1/S1, and *S2/S2. Among An. arabiensis, we identified *R2/R2, *S1/S1, and *S2/S2. Tests on haplotype diversity showed that the most diverse allele was TEP1*S1, followed by TEP1*R2. Tajima’s D values were positive for TEP1*S1, indicating that there is a balancing selection, negative for TEP1*R2, indicating there is a recent selective sweep, and as for TEP1*R3, there was no evidence of selection. Phylogenetic analysis showed two distinct clades: refractory and susceptible alleles.

Conclusions

We find that the malaria vectors An. gambiae s.l. and An. funestus are predominantly exophilic. TEP1 genotyping for An. merus revealed five allelic combinations, namely *R2/R2, *R3/R3, *R3/S2, *S1/S1 and *S2/S2, while in An. arabiensis we only identified three allelic combinations: *R2/R2, *S1/S1, and *S2/S2. The TEP1*R3 allele was restricted to only An. merus among these sympatric mosquito species, and we find that there is no evidence of recombination or selection in this allele.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria remains one of the most important infectious diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, responsible for approximately 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths in 2020 [1]. Significant advances in malaria control have been achieved in the last two decades, mostly by vector control interventions including long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS). Between 2000 and 2019 we saw a reduction of 28% and 44% in global malaria incidence and mortality, respectively [2, 3]. Unfortunately, this progress has plateaued in the last 5 years, and the World Health Organization (WHO)’s 2016–2030 global technical strategy for malaria (GTS) [4] is off-track, with a global incidence reduction of less than 2% between 2015 and 2020 [1].

Malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa is mainly driven by mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae and, more recently, Anopheles funestus complexes [5,6,7]. Despite the scale-up of malaria control interventions, insecticide resistance [6, 8] and increased vector behavioural plasticity [9,10,11,12,13] are threatening the gains made in malaria control. This, therefore, calls for the development of more effective novel interventions such as transmission-blocking vaccines or gene drive systems that can lead to population replacement of infection-susceptible mosquitoes with those that are refractory to Plasmodium spp. infection [14].

Although there are 475 Anopheles species, only 70 are known primary or secondary vectors of malaria [15]. This is partly attributable to the mosquito’s innate immunity against invading parasites [16, 17]. One such anti-parasitic immunity is mediated by thioester-containing protein 1 (TEP1), a homologue of the mammalian complement factor 3. TEP1 recognises and binds to ookinetes, mediating parasite lysis and melanisation [8]. TEP1 is a highly polymorphic protein consisting of variants differentiated by amino acid sequence variation in the thioester domain (TED) region [18]. The variants are classified into two main subclasses: refractory TEP1*R (*R1 and *R2) and susceptible TEP1*S (*S1 and *S2). Mosquitoes bearing the R alleles are more effective at parasite killing, with *R1/R1 and *S2/S2 mosquitoes being fully resistant and susceptible to infection, respectively [16]. The TEP1*S and TEP1*R alleles are found in all species of An. gambiae s.l., albeit with marked variation in distribution both geographically and within the different species. Additionally, TEP1 alleles have been shown to affect male fitness in wild mosquito populations, and due to their ability to clear off defective sperms, mosquitoes bearing the TEP1*S2 alleles have been shown to have higher fertility rates [19].

Recently, a novel resistance-encoding allele, termed TEP1*R3, was discovered in Anopheles merus populations from the Kenyan coast [20]. Its genetic diversity and functional role in controlling the development of malaria parasites within the mosquito have not been described. The present study aimed at characterising the TEP1 alleles of An. merus populations collected from coastal Kenya.

Methods

Study area

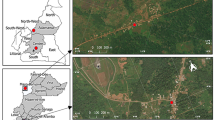

Entomological collections were conducted in Garithe village, Kilifi County, along the Kenyan coast (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). This region is highly diverse, made up of dense forests, dry thorny bushes, savannah vegetation, and seasonal swamps of brackish water. There are two distinct rainy seasons: long rains which occur between April and July, and short rains between October and November [21]. The site was targeted for collections based on previous studies that described An. merus in high density [22].

Mosquitoes were collected in 20 houses over six consecutive days during the month of November in 2019 (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Collections were carried out using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention light traps (CDC-LT) both indoors and outdoors for each house from dusk (1800 h) to dawn (0600 h), whilst coordinates were collected using eTrex® 10 (Garmin, Kansas, United States of America). The indoor traps were set in houses where at least one person spent the night during the collection period. The outdoor traps were strategically set next to the livestock shed, and where livestock were absent, the trap was set approximately 5 m from the household selected for indoor sampling. The collected mosquitoes were identified morphologically in the field laboratory [23] and sorted by physiological stage and sex. All the Anopheles spp. were preserved individually in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes containing silica pellets and transported to the KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP) laboratory and stored at −80 °C.

Mosquito processing

Using sterile scalpel and forceps, the female Anopheles mosquitoes were dissected and separated into distinct body parts for different assays. The legs and wings were used for An. gambiae s.l. sibling species identification, the head and thorax for the Plasmodium falciparum infection status, and the abdomen of blood-fed mosquitoes for trophic pattern and preference analysis as described previously [24].

Anopheles gambiae s.l. sibling species identification

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from the legs and wings of mosquitoes as described previously, with minor modifications [25]. Briefly, the mosquito parts were transferred into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes containing 50 µl of 20% Chelex and crushed using polypropylene pestles. The lysate was incubated at 100 °C while shaking at 650 revolutions per minute (rpm) using a ThermoMixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The solution was then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 2 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube. This was repeated twice, and the DNA was stored at −80 °C.

Anopheles gambiae s.l. sibling species were identified using a previously described method using primers that target the intergenic spacer (IGS) region of the ribosomal DNA [26]. The species were distinguished by their band sizes after running agarose gel electrophoresis as follows: 153 base pairs (bp) for Anopheles quadriannulatus, 315 bp for An. arabiensis, 390 bp for An. gambiae sensu stricto, 464 bp for Anopheles melas, and 466 bp for An. merus [26]. Anopheles funestus complex sibling species were also identified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers targeting the internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) [27].

Blood meal analysis

The abdomens of the blood-fed female Anopheles mosquitoes were crushed in 50 µl of molecular-grade water using sterile polypropylene pestles. Thirty microlitres of the lysate was mixed with 500 µl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then used to determine the source of blood meal using direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) as described previously [28, 29], with slight modifications. The samples were tested against the anti-host immunoglobulin G (IgG): human, goat, bovine, and chicken. The results were read visually as described previously [30].

Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite analysis

The mosquito head and thorax were crushed in 100 µl of 1× PBS in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. Then, 10 µl of 10× saponin was added to the lysate. The solution was subsequently incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and then centrifuged at 20,000×g for 2 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in 100 µl 1× PBS. The solution was then centrifuged at 2000×g for 2 min and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in 50 µl of 20% Chelex and DNA extracted using the procedure described above. Thereafter, the extracted DNA was used for SYBR Green real-time PCR (RT-PCR) assays using primers described in Hermsen et al. [31]. Briefly, the RT-PCR reaction consisted of 7.5 µl of QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR master mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 7.5 µM of forward primer 5′-GTAATTGGAATGATAGGATTTACAAGGT-3′ and 7.5 µM of the reverse primer 5′-TCAACTACGAACGTTTTAACTGCAAC-3′, 2 µl of nuclease-free water, and 4 µl of the DNA. RT-PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min for HotStarTaq DNA Polymerase activation, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 45 s, 68 °C for 45 s, and finally the melt curve phase: 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 30 s.

TEP1 genotyping

The highly polymorphic TED region of TEP1 was amplified using the primers VB229 5′-TCAACTTGGACATCAACAAGAAG-3′ and VB004 5′-ACATCAATTTGCTCCGAGTT-3′ as described previously [19, 32]. Thereafter, the 1088 ± 1-bp amplicon was cleaned using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and eluted in 15 µl of DNase-free water. The samples were subjected to both Sanger and next-generation sequencing (NGS).

For the Sanger sequencing, the PCR amplicons were sequenced using the primers (VB004 and VB229), BigDye Terminator chemistry v 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, UK), and the reaction was run on an ABI 3730xl capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, UK). The resulting sequence chromatograms were curated, edited, and aligned using the CLC Main Workbench 7 (CLC Bio, Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark).

For NGS, 75 cycles of paired-end sequencing were carried out on the MiSeq platform using the Nextera DNA Flex library preparation protocol and MiSeq reagent kit v 3 (Illumina, USA). The resulting reads were demultiplexed, and then FastQC v 0.11.9 was used to remove indexes, low-quality PhiX and adapter reads. The identity of the resulting reads was ascertained using both BLASTn v 2.11.0 and mapping onto the TEP1 references.

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignment and sequence editing was conducted in AliView v 1.25 software, using the newly sequenced TEP1-TED sequences and those collated from GenBank [33]. Maximum likelihood phylogenies were reconstructed using the TIM+F+I substitution model with four gamma categories (TIM+F+I+G4) as the best fitting model as inferred by jModelTest in iqtree v 1.6.9 [34] and visualised using FigTree v 1.4.4.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis, visualisation, and mapping were performed using R software (v 4.1.0) [35]. The data were further analysed using a generalised negative binomial regression model with a log link and robust errors, where the dependent variable was the number of mosquitoes collected, and the independent variables were site (indicator variable), day, and household using STATA v 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The human blood index (HBI) was calculated as the proportion of mosquitoes that had fed on humans divided by total blood meals tested for each species.

Haplotype statistics including the number of haplotypes, haplotype frequency, and haplotype configuration, and tests of natural selection including Tajima’s D [36], Fu and Li’s D, and Fu and Li’s F [37] were calculated using DNA Sequence Polymorphism (DnaSP) software [38].

Results

Abundance and diversity of Anopheles spp. mosquitoes

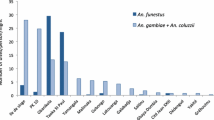

A total of 18,802 mosquitoes were collected. Based on morphological cues, the mosquito species consisted of 77.8% (n = 14,631) Culex spp., 21.4% (n = 4026) An. gambiae s.l., 0.4% (n = 67) An. funestus, and 0.4% (n = 78) other Anopheles (An. coustani, An. pharoensis, An. pretoriensis). A subset of the Anopheles gambiae s.l. (n = 518) mosquitos were analysed for sibling species by PCR. Of these, 77.2% (n = 400) were identified as An. merus, 22% (n = 114) as An. arabiensis, and 0.8% (n = 4) were not detected by PCR. This could be due to very low DNA concentrations, the presence of PCR inhibitors, or morphological misidentification (Fig. 1). Anopheles funestus complex consisted of 42% (n = 28) An. rivulorum, 25% (n = 17) An. leesoni, and 3% (n = 2) An. parensis, and the rest could not be detected (30%, n = 20).

A greater proportion of all the mosquito species collected were found outdoors (Table 1). Ninety-one percent of the An. funestus mosquitoes collected were caught outdoors (IRR = 10.3, 95% Cl [3.3–32.3]; P < 0.001). The same was observed for An. gambiae s.l., at 92% (IRR = 7.2, 95% Cl [3.6–14.5]; P < 0.001), and Culex spp. at 93% (IRR = 11.6, 95% Cl [5.9–22.9] P < 0.001).

Physiological state and source of blood meal

Generally, there are a greater number of mosquitoes in all the physiological states found outdoors (Additional file 2: Table S1). Of those that were blood-fed, 90 mosquitoes belonged to the An. gambiae complex and five to the An. funestus complex. Those analysed for blood meal source consisted of 79% (n = 71) An. merus and 14.4% (n = 13) An. arabiensis. Among An. merus collected outdoors, a greater proportion had fed on goats (77.1%, n = 54), and 2.8% (n = 2) had fed on humans (HBI = 0.03). The HBI was however slightly higher indoors (HBI = 0.14). Among An. arabiensis collected outdoors, 38.5% (n = 5) had fed on goats and 23.1% on humans (n = 3, HBI = 0.27) (Table 2).

Plasmodium infection in mosquitoes

Of the 4026 An. gambiae s.l., 281 mosquitoes (An. arabiensis [n = 70] and An. merus [n = 211]) were screened for sporozoite infection by PCR (Additional file 2: Table S1). From these, 9.5% (20/211) An. merus and 8.6% (6/70) An. arabiensis were sporozoite-positive. Furthermore, a greater number of mosquitoes from outdoor catches were sporozoite-positive for both species (Additional file 3: Table S2).

TEP1 distribution

We genotyped 175 samples from both An. merus and An. arabiensis. The *R2/R2 (84%, n = 32) allele was predominant in An. arabiensis, followed by *S2/S2 (11%, n = 4) (Fig. 2). For An. merus, the predominant allele was *S1/S1 (66%, n = 91), followed by *R3/R3 (22%, n = 30) (Fig. 2). At the household level, the *R2/R2 allele among An. arabiensis and *S1/S1 among An. merus were common for all the houses that were analysed (Fig. 3). Additionally, *R3/R3 and *R3/S2 genotypes were restricted to An. merus mosquitoes. In further analysis between TEP1 alleles and P. falciparum positivity, only An. merus and An. arabiensis with the *R2/R2 and *S1/S1 alleles were positive for P. falciparum sporozoites (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Haplotype statistics

Full-length TEP1-TED sequences were used for haplotype statistics and test of neutrality (n = 110, length = 758 bp) (Table 3). The abundance of haplotypes among the specific alleles was highest in TEP1*S1. Haplotype diversity ranged from 0 to 0.999, with TEP1*S1 having the highest value (0.999) and TEP1*R3 with the lowest (Table 3).

TEP1 phylogenetics

Generally, two major clades exist, with the susceptible (TEP1*S) and resistant (TEP1*R) genotypes having evolved separately and independently of each other (Fig. 4). The distribution of these alleles was not mosquito species-specific except for TEP1*R3, which was only found among An. merus mosquitoes. Amongst the susceptible, two further subclades exist (TEP1*S1 and TEP1*S2) that are evolving independently of each other since last separating from their most recent common ancestor (MRCA). The TEP1*S1 allele is the most prevalent overall, and more diverse than TEP1*S2. Amongst the mosquitoes carrying the resistant allele, two subclades exist (TEP1*R1-TEP1*R2 and TEP1*R3). TEP1*R1 and TEP1*R2 are closely related, with the former forming a subclade nested within TEP1*R2.

Maximum likelihood tree on the TEP1-TED domain of sequences from Garithe as well as GenBank. There are two clades: the susceptible (TEP1*S) and refractory (TEP1*R). Among the susceptible, two subclades, TEP1*S1 (green) and TEP1*S2 (blue), appear to be evolving independently of each other. Among the refractory alleles, TEP1*R1 (yellow) and TEP1*R2 (pink) are closely related, with TEP1*R1 forming a subclade nested within TEP1*R2. TEP1*R3 (grey) is restricted to An. merus

Discussion

Anopheles merus was the predominant mosquito from the An. gambiae complex, constituting 77.2% of those that were identified by PCR, which is consistent with previous studies in the same area [21, 22, 39]. In contrast to other studies, we did not find any An. gambiae s.s., and therefore we assume that they may have been cleared by interventions such as IRS and LLINs [9, 40]. We also found that the majority of the mosquitoes were outdoor feeders, which could also be due to pressure from insecticides, as previously observed in Tanzania among An. funestus mosquitoes [9]. Additionally, An. arabiensis and An. merus have been shown to be exophilic and zoophilic [22, 39, 41, 42].

Anopheles merus is an important vector of P. falciparum and Wuchereria bancrofti. This mosquito species is especially notorious for its exophilic tendencies. From the 18s rRNA PCR, we identified a P. falciparum infection rate of 9.5% (20/210) in An. merus and 8.6% (6/70) in An. arabiensis, with a majority of these being outdoor feeders, meaning they may be involved in outdoor malaria transmission. Of note, the blood-fed mosquitoes identified either indoor or outdoor exhibited relaxed feeding preference by drawing blood meals from a variety of vertebrate hosts including humans, goats, and bovines.

Of interest for the TEP1 alleles analysed, the TEP1*S1/S1 was the most prevalent allele (66%) and the only allele positive for sporozoite infection (n = 6). We also found the TEP1*R3 allele exclusively in An. merus, though being sympatric with An. arabiensis, which is consistent with previous findings [20, 43]. However, the function of the TEP1*R3 allele is yet to be elucidated, although our data suggest that they may be associated with mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium infection, since none of the genotyped TEP1*R3 mosquitoes were positive for P. falciparum. The TEP1*R3 allele was fairly well distributed in Garithe and found in about a third of sampled houses (Fig. 3). The *S1/S1 and *R3/R3 genotypes were enriched in An. merus similar to previous findings [20, 43]. The *R1/R1 allele is more efficient in parasite clearance than *R2/R2, with *S2/S2 and *S1/S1 being fully susceptible.

The tests on haplotype diversity showed that the most diverse allele was TEP1*S1, followed by TEP1*R2 (Table 3). The low nucleotide diversity values for all the alleles indicate that there is a modest difference among the alleles. Tajima’s D values were positive for TEP1*S1, indicating that there is a balancing selection, and negative for TEP1*R2, indicating a recent selective sweep. As for TEP1*R3, there is no evidence of selection. Lastly, the Fu and Li’s D and F statistics were calculated, where all the values were positive, ranging from 0 to 2.398, indicative of a few unique variants and an abundance of the present variants.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the refractory and susceptible TEP1 alleles emerged independently of each other, as shown in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). They exist as separate clades, each clade evolving uniquely and exhibiting high diversity. The separate emergence and evolution of the refractory and susceptible alleles is likely due to two different gene conversions in the TEP1 loci [18]. The resistant and susceptible alleles have previously been reported to be recombinants and under positive selection [18]. It is also clear that the TEP1*R3 is restricted to the saltwater breeding An. merus from the Kenyan coast: Kwale and Kilifi counties. Why the allele is present in these mosquitoes is still a mystery and yet to be elucidated.

Conclusions

Anopheles merus, a saltwater breeding mosquito vector of malaria and lymphatic filariasis, was the dominant species of An. gambiae complex identified in Garithe village in coastal Kenya. Mosquitoes in the study area were predominantly exophilic and utilised a variety of vertebrate hosts for blood meal requirements. Our observation of the abundance of the P. falciparum fully susceptible TEP1*S1 allele shows that the area has a huge number of mosquitoes that are ready to transmit malaria. This is evidenced by the high number of sporozoite-positive mosquitoes with the *S1/S1 genotype among An. merus mosquitoes. In addition, TEP1*S1 mosquitoes were predominantly exophilic, meaning that indoor adult mosquito control strategies may be ineffective for their control. This fact might suggest a potential risk of these mosquitoes becoming major players in persistent outdoor malaria transmission. Mosquitoes bearing the TEP1*R3 allele were the second most frequently found, and although the role of this allele in malaria has not been established, it is unlikely that they would support malaria given they were negative for P. falciparum infection and the fact that they belong to a family of refractory alleles. However, this needs further confirmation by experimental infections. Of interest the TEP1*R3 allele seems to be mosquito species-specific i.e. only found in An. merus that were also negative for P. falciparum infection. This obersavation suggests the TEP1*R3 allele has potential for consideration as candidate molecule for malaria transmission blocking through applictions such as gene drive systems.

Availability of data and materials

The data and the analysis codes used in R (v 4.0.1) are available in the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/CKMX29. The sequences have been deposited at GenBank under accession numbers OM237458–OM237611.

Abbreviations

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DnaSP:

-

DNA Sequence Polymorphism software

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- KWTRP:

-

KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- ITS:

-

Intergenic spacer

- LLINs:

-

Long-lasting insecticide-treated nets

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- TEP1*R:

-

TEP1-refractory

- RT-PCR:

-

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- TEP1*S:

-

TEP1-susceptible

- TED:

-

Thioester domain

- TEP1 :

-

Thioester-containing protein 1

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO (World Health Organization). World malaria report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

WHO (World Health Organization). World malaria report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

WHO. World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

WHO. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 1–35.

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Coetzee M, Mbogo CM, Hemingway J, et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-3-117.

Matowo NS, Martin J, Kulkarni MA, Mosha JF, Lukole E, Isaya G, et al. An increasing role of pyrethroid—resistant Anopheles funestus in malaria transmission in the Lake Zone, Tanzania. Sci Rep. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92741-8.

Kaindoa EW, Matowo NS, Ngowo HS, Mkandawile G, Mmbando A, Finda M, et al. Interventions that effectively target Anopheles funestus mosquitoes could significantly improve control of persistent malaria transmission in south-eastern Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177807.

Munywoki DN, Kokwaro ED, Mwangangi JM, Muturi EJ, Mbogo CM. Insecticide resistance status in Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) in coastal Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04706-5.

Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killeen GF. Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011;10:80.

Fornadel CM, Norris LC, Glass GE, Norris DE. Analysis of Anopheles arabiensis blood feeding behavior in southern Zambia during the two years after introduction of insecticide-treated bed nets. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:848–53.

Reddy MR, Overgaard HJ, Abaga S, Reddy VP, Caccone A, Kiszewski AE, et al. Outdoor host seeking behaviour of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes following initiation of malaria vector control on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2011;10:1–10.

Sokhna C, Ndiath MO, Rogier C. The changes in mosquito vector behaviour and the emerging resistance to insecticides will challenge the decline of malaria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:902–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12314.

Sharp BL, le Sueur D. Behavioural variation of Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae) populations in Natal, South Africa. Bull Entomol Res. 1991;81:107–10.

Blandin S, Shiao SH, Moita LF, Janse CJ, Waters AP, Kafatos FC, et al. Complement-like protein TEP1 is a determinant of vectorial capacity in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Cell. 2004;116:661–70.

(WRBU) TWRBU. The Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit (WRBU). 2021. https://www.wrbu.si.edu/vectorspecies/genera/anopheles.

Blandin SA, Wang-Sattler R, Lamacchia M, Gagneur J, Lycett G, Ning Y, et al. Dissecting the genetic basis of resistance to malaria parasites in Anopheles gambiae. Science (80-). 2009;326:147–50.

Smith RC, Vega-Rodríguez J, Jacobs-Lorena M. The Plasmodium bottleneck: malaria parasite losses in the mosquito vector. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:644–61.

Obbard DJ, Callister DM, Jiggins FM, Soares DC, Yan G, Little TJ. The evolution of TEP1, an exceptionally polymorphic immunity gene in Anopheles gambiae. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:1–11.

Pompon J, Levashina EA. A new role of the mosquito complement-like cascade in male fertility in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:1–17.

Gildenhard M, Rono EK, Diarra A, Boissière A, Bascunan P, Carrillo-Bustamante P, et al. Mosquito microevolution drives Plasmodium falciparum dynamics. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:941–7.

Mbogo CM, Mwangangi JM, Nzovu J, Gu W, Yan G, Gunter JT, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of Anopheles mosquitoes and Plasmodium falciparum transmission along the Kenyan coast. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:734–42.

Kipyab PC, Khaemba BM, Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM. The bionomics of Anopheles merus (Diptera: Culicidae) along the Kenyan coast. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:37.

Gillies MT, De Meillon B. The Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara (Ethiopian zoogeographical region). Anophelinae Africa south Sahara (Ethiopian Zoogeographical Reg). 1968.

Mwangangi JM, Muturi EJ, Muriu SM, Nzovu J, Midega JT, Mbogo C. The role of Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles coustani in indoor and outdoor malaria transmission in Taveta District, Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:114.

Musapa M, Kumwenda T, Mkulama M, Chishimba S, Norris DE, Thuma PE, et al. A simple Chelex protocol for DNA extraction from Anopheles spp. J Vis Exp. 2013;9:0–6.

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–9.

Koekemoer LL, Kamau L, Hunt RH, Coetzee M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;6:804–11.

Beier JC, Perkins PV, Wirtz RA, Koros J, Diggs D, Gargan TP, et al. Bloodmeal identification by direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), tested on Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) in Kenya. J Med Entomol. 1988;25:9–16.

Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Nzovu JG, Githure JI, Yan G, Beier JC. Blood-meal analysis for anopheline mosquitoes sampled along the Kenyan coast. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2003;19:371–5.

Beier JC, Koros JK. Visual assessment of sporozoite and bloodmeal ELISA samples in malaria field studies. J Med Entomol. 1991;28:805–8.

Hermsen CC, Telgt DSC, Linders EHP, Van De Locht LATF, Eling WMC, Mensink EJBM, et al. Detection of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites in vivo by real-time quantitative PCR. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;118:247–51.

Smidler AL, Terenzi O, Soichot J, Levashina EA, Marois E. Targeted mutagenesis in the malaria mosquito using TALE nucleases. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:1–9.

National Library of Medicine (US) NC for BI. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 1988. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Accessed 15 Dec 2021.

Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Michael D, Von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–4.

Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vol. 3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. http://www.r-project.org/.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–95.

Fu YX, Li WH. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:693–709.

Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–2.

Bartilol B, Omedo I, Mbogo C, Mwangangi J, Rono MK. Bionomics and ecology of Anopheles merus along the East and Southern Africa coast. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04582-z.

Mwangangi JM, Midega JT, Keating J, Beier JC, Borgemeister C, Mbogo CM, et al. Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013;12:1–9.

Mahande A, Mosha F, Mahande J, Kweka E. Feeding and resting behaviour of malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis with reference to zooprophylaxis. Malar J. 2007;6:1–6.

Bamou R, Rono M, Degefa T, Midega J, Mbogo C, Ingosi P, et al. Entomological and anthropological factors contributing to persistent malaria transmission in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Cameroon. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:S155–70.

Rono EK. Variation in the Anopheles gambiae TEP1 gene shapes local population structures of malaria mosquitoes. Dissertation, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18452/18573

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Garithe community for allowing us to carry out the study in their homesteads. Many thanks to the technical and field staff: Festus Yaa, and Gabriel Nzai who devoted their time to assist in the field collection of mosquito samples.

Funding

This work is supported by The Royal Society FLAIR fellowship grant FLR_R1_190497 (awarded to MKR). The funding bodies had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BB, JK, KO identified the mosquitoes; BB, DO carried out the bioinformatics analysis; BB, MM, MK carried out statistical analysis; CM, JM, MM, MK revised and provided critical reviews on the manuscript. MK designed, supervised, and provided funding for the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the KEMRI Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU) (Protocol number: KEMRI/SERU/CGMR-C/024/3148). Oral consent was obtained from the household head before mosquito collections commenced.

Consent for publication

The authors declare no competing interests of financial or non-financial nature. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by any of the authors or respective affiliations.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Figure S1. The respective houses in Garithe village where mosquitoes were sampled.

Additional file 1

: Table S1. The P. falciparum sporozoite rates between the different TEP1 genotypes among An. merus and An. arabiensis mosquitoes.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

The sporozoite rates between indoor and outdoor collected mosquitoes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartilol, B., Omuoyo, D., Karisa, J. et al. Vectorial capacity and TEP1 genotypes of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato mosquitoes on the Kenyan coast. Parasites Vectors 15, 448 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05491-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05491-5