Abstract

Background

Dengue is prevalent worldwide and is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Temperature is a strong driver of dengue transmission. However, little is known about the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Aedes albopictus mosquitoes exposed or not exposed to dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) were reared at 23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C, and midguts and residual tissues were evaluated at 7 days after infection. RNA sequencing of midgut pools from the control group, midgut breakthrough group and midgut nonbreakthrough group at different temperatures was performed. The transcriptomic profiles were analyzed using the R package, followed by weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis to identify the important molecular mechanisms regulated by temperature.

Results

The midgut infection rate and midgut breakthrough rate at 28 °C and 32 °C were significantly higher than those at 23 °C, which indicates that high temperature facilitates DENV-2 breakthrough in the Ae. albopictus midgut. Transcriptome sequencing was performed to investigate the antiviral mechanism in the midgut. The midgut gene expression datasets clustered with respect to temperature, blood-feeding and midgut breakthrough. Over 1500 differentially expressed genes were identified by pairwise comparisons of midguts at different temperatures. To assess key molecules regulated by temperature, we used WGCNA, which identified 28 modules of coexpressed genes; the ME3 module correlated with temperature. KEGG analysis indicated that RNA degradation, Toll and immunodeficiency factor signaling and other pathways are regulated by temperature.

Conclusions

Temperature affects the infection and breakthrough of Ae. albopictus midguts invaded by DENV-2, and Ae. albopictus midgut transcriptomes change with temperature. The candidate genes and key pathways regulated by temperature provide targets for the prevention and control of dengue.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dengue fever is an arthropod-borne disease caused by the dengue virus (DENV) [1]. In general, clinical manifestations vary after infection with DENV. Most people are asymptomatic or have only minor symptoms, including fever, rash, and body pain. However, a proportion of patients develop severe dengue, which manifests as severe bleeding, shock, and even death [2]. Although dengue is endemic worldwide, it is distributed mainly in tropical and subtropical regions. It is estimated that approximately 400 million people are infected with DENV globally every year, with 25% of this population presenting clinical symptoms [3]. In recent years, dengue outbreaks have appeared in the Americas, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Nepal [4,5,6,7]. In China, dengue frequently occurs in the provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan. In 2014, the largest outbreak was reported in Guangdong Province, with 47,056 cases and six deaths [8, 9]. The area endemic for dengue is constantly expanding, and the number of people at risk increases yearly.

Dengue is transmitted by mosquitoes of the genus Aedes, such as Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Aedes aegypti is internationally recognized as the principal vector of dengue; Ae. albopictus is the secondary vector [10]. In China, the distribution of Ae. aegypti is limited to only a few areas of Guangdong, Hainan and Yunnan, and Ae. albopictus is the dominant mosquito species that causes dengue outbreaks in China; Ae. albopictus is distributed in perennially warm provinces and the north, southwest and southeast coastal areas [11]. Moreover, the geographical distribution of Ae. albopictus is continuing to expand with the acceleration of global warming, urbanization and trade, with an increased risk of the spread of dengue.

Temperature affects the prevalence of dengue [12, 13], and in the absence of measures to mitigate climate change, an additional 7.5 million dengue cases per year could occur. If the increase in temperature remains within 2 °C, the annual increase in dengue cases could be reduced by 1–3 million; if it is controlled to within 1.5 °C, the number of cases could be further reduced [14]. In general, the risk of dengue increases with increasing temperature, which is primarily associated with improving the vector competence of mosquitoes to transmit DENV. In one study, when the temperature was higher than 26 °C, the extrinsic incubation period of DENV in Ae. aegypti was approximately 1 week, but was longer when the temperature was lower than 21 °C; when the temperature was lower than 18 °C, Ae. aegypti could not transmit DENV [15]. Similar results were shown for Ae. albopictus [16]. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which temperature affects the transmission of DENV by Aedes remains unclear.

Mosquito-borne viruses must overcome a mosquito’s midgut and salivary gland barrier to replicate; indeed, the midgut is the first barrier against a virus. Thus, the equilibrium of the midgut environment affects viral replication [17, 18]. For example, in Ae. aegypti infected with Zika virus and cultured at 20 °C, 28 °C, and 36 °C, the gene expression profiles of the midgut change with temperature, especially under low-temperature conditions (20 °C), with significant alterations in gene expression related to blood digestion, active oxygen metabolism and innate immunity [19].

Our previous research showed that DENV serotype 2 (DENV-2) is confined to the midgut of Ae. albopictus and slowly proliferates at 18 °C; when the temperature is 23–32 °C, DENV-2 breaks through the midgut barrier of Ae. albopictus and invades the salivary glands [16]. To better understand the interaction between Ae. albopictus and DENV-2 under different temperatures, the infection status in the midgut and residual tissues of Ae. albopictus at 23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C was investigated. Transcriptome sequences were obtained from the midgut of Ae. albopictus. In addition, gene network modules highly related to temperature were identified using weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA).

Methods

Mosquitoes

Aedes albopictus were collected in Foshan city, Guangdong Province, China, and bred in a standardized room (constant 27 ± 1 °C, 70–80% relative humidity and a 16 h:8 h light–dark photoperiod). The eggs hatched into larvae in dechlorinated water, and the larvae were fed turtle food until the pupal stage. The pupae were transferred into a cup and placed in a mosquito cage. Adults emerged during a period of 2–3 days and were fed 10% glucose. The mosquitoes were fed defibrinated sheep blood for egg production.

The proliferation of DENV

Experiments with DENV-2 were performed in a biological safety cabinet. DENV-2 (New Guinea C) proliferated in C6/36 cells. C6/36 cells cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum were inoculated with DENV-2 at a multiplicity of infection of 1; the culture flask was gently shaken for 15 min at room temperature and subsequently incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2 days. The supernatant was harvested after centrifugation at 1500× g for 5 min. The DENV-2 titer was determined based on the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) [20].

Mosquito infection with DENV-2

The mosquito infection experiment was performed in a biosafety level 2 laboratory. Five- to 7-day-old female Ae. albopictus mosquitoes were starved for 16–20 h. Fresh DENV-2 (8.625 log10 TCID50/mL) was mixed with defibrinated sheep blood at a ratio of 2:1. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the blood meal was transferred into a Hemotek blood reservoir unit (Discovery Workshops, Lancashire, UK). Aedes albopictus mosquitoes were allowed to feed on the blood meal for 30 min. The engorged mosquitoes were anesthetized with CO2, placed in 250-mL paper cups covered with gauze (10 mosquitoes/cup), and maintained in different incubators precisely set at 23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C, 80% relative humidity and a 16 h:8 h (light:dark) photoperiod. For the control (CT) group, DENV-2 was replaced with RPMI-1640/2% fetal bovine serum. All mosquitoes were fed 10% glucose solution. Three batches of mosquito infections were performed for each temperature.

DENV-2 detection

The midgut and residual tissues of each mosquito were dissected and individually examined at 7 days post-infection. The tissues from 466 mosquitoes that had ingested viral blood meals and 90 mosquitoes comprising the CT groups were tested for DENV-2 infection. Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using 4 µL of RNA and random primers following the manufacturer’s recommendations for the GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega). DENV-2 positivity was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using previously described primers (forward primer, 5ʹ-TCAATATGCTGAAACGCGCGAGAAACCG-3ʹ; reverse primer, 5ʹ-TTGCACCAACAGTCAATGTCTTCAGGTTC-3ʹ) [21]. PCR was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the Maxima Hot Start Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The 511-bp target fragment was identified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The residual RNA was stored at − 80 °C.

Determination of the midgut infection, midgut breakthrough and midgut nonbreakthrough rates of Ae. albopictus

When DENV-2 was simultaneously detected in the midgut and the residual tissue of Ae. albopictus, it was considered to have broken through the midgut barrier of the mosquitoes; these mosquitoes constituted the midgut breakthrough (MB) group. When DENV-2 was detected only in the midgut and not in residual tissue, it was considered to have not broken through the midgut barrier; these mosquitoes constituted the midgut nonbreakthrough (MNB) group. The midgut infection rate (MIR), midgut breakthrough rate (MBR), and midgut nonbreakthrough rate (MNBR) of Ae. albopictus were determined using the following formulas:

Library preparation and RNA sequencing

Midguts from the control (CT), MB and MNB groups at each temperature (23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C) were selected and divided into nine groups according to the results of the above experiment. The quality and integrity of a single midgut were tested using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA); midgut RNA concentrations were detected using a Nanodrop 2000. Three midgut samples of each group were mixed to form a pool, and each group had three biologically repeated pools. The biological replicates of midgut pools were from different feeding batches. In total, 27 pools were sent to Wuhan Huada Medical Laboratory for RNA sequencing. Total RNA was purified with the messenger RNA enrichment method or ribosomal RNA removal method, and a cDNA library was constructed. The prepared libraries were sequenced with DNASeqPE150 (BGI, China).

RNA sequence analysis in response to temperature and DENV-2 exposure

The raw data obtained by RNA sequencing were filtered to remove low-quality data, contaminating linkers, and a high N content of unknown bases. The filtered data, as clean reads, were compared with the genome of the Foshan strain of Ae. albopictus (AaloF1, VectorBase, https://www.vectorbase.org), and novel transcripts were analyzed. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to evaluate the sample repeatability and overall differences between samples. The gene length and total reads were normalized. Relative expression levels were assessed as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM). Intragroup and intergroup Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated according to FPKM values, and a heat map was drawn.

Identification of differentially expressed genes and coexpression network modules

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed and visualized using the Ballgown package (version 2.16.0) and ggplot2 (version 3.3.5) in R (version 4.0.5) [22]. The DEGs of the MB and MNB groups at each temperature and those between two adjacent temperatures in the MB or MNB groups are illustrated by a Venn diagram. DEGs were identified as genes with twofold or more changes between samples and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. WGCNA of all genes (FPKM > 1) was performed using the WGCNA (version 1.69) package [23]. An adjacency matrix of the genes’ similarity was conducted by pairwise Pearson correlation analysis. Using an appropriate soft threshold, β = 4 was obtained based on the pickSoftThreshold function. The cluster dendrogram plot and clustering tree of coexpression gene modules of all genes were constructed with the parameters of cutHeight = 0.75 and minSize = 30. Module-trait relations were evaluated through module eigengenes (MEs). The relationships between MEs and traits (temperature, treatment with or without virus, and tested positive or negative) were visualized through a heat map, and assessed by P-values and linear regression between gene expression profile and each trait. Modules significantly associated with the traits were identified by |cor | > 0.5 and P < 0.05 and considered to be the key modules. Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses of the genes in key modules were analyzed using ClusterProfiler version 4.1 [24].

Quantitative real-time PCR

The genes regulated by temperature were validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The levels of 18 genes were determined in the midguts at different temperatures. RNA and cDNA were synthesized using the above-described protocol. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate for each sample with SYBR Green Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Gene expression was normalized to that of RPS7. The primer sequences are listed in Additional file 3: Table S1. The program was 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 10 s.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL). MIR, MBR, and MNBR for Ae. albopictus infected with DENV-2 were separately compared at different temperatures using chi-square (and Fisher’s exact) tests. P-values were corrected by Bonferroni adjustment. The interaction between temperature and viral ability to escape midgut was determined by a multivariate ANOVA. The expression levels of genes were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis H-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Temperature affects DENV-2 infection and midgut breakthrough in Ae. albopictus

The DENV-2 titer was determined to be 8.625 log10 TCID50/mL. In total, 466 Ae. albopictus mosquitoes that ingested blood meals containing DENV-2 were used to analyze the midgut infection and breakthrough rates at 23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C. The MIR was significantly higher at 28 °C and 32 °C than at 23 °C (χ2 = 9.658, P < 0.01; χ2 = 16.909, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1a). Although the MIR was higher at 32 °C than at 28 °C, there was no significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 3.001, P = 0.107) (Fig. 1a). The MBR of Ae. albopictus infection by DENV-2 was closely related to temperature and gradually increased when the temperature increased, although the MNBR gradually decreased. The MBR was significantly higher at 28 °C and 32 °C than at 23 °C (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, respectively), whereas the MNBR had the opposite trend (Fig. 1b). The MNBR was significantly higher than the MBR at 23 °C, but the MBR was significantly higher than the MNBR at 28 °C and 32 °C (Fig. 1b). The interaction between temperature and viral ability to escape the midgut was determined by a multivariate ANOVA. The result showed that temperature had a significant effect on viral ability to escape midgut.

Analysis of the midgut of Aedes albopictus infected with dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) at different temperatures. Aedes albopictus orally infected with DENV-2 were reared at 23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C. The midguts and residual tissue were dissected at 7 days post-infection, and DENV-2 was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). a Midgut infection rate. b Analysis of midgut breakthrough [midgut breakthrough rate (MBR), midgut nonbreakthrough rate (MNBR)] in Ae. albopictus at different temperatures. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, ns nonsignificant

Characterization of Ae. albopictus transcriptomes at different temperatures

Transcriptome sequencing was performed on 27 samples from the CT, MB, and MNB groups at different temperatures (23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C). Clean reads were obtained after removing low-quality data, and trimmed reads were obtained. Nearly 80% of the reads were mapped to the Ae. albopictus Foshan strain genome (Table 1).

PCA was used to analyze the variance of within-group samples and gene expression patterns associated with temperature, infection and breakthrough of the midgut. The PCA plot showed a high degree of reproducibility among replicate samples (Fig. 2a), and gene expression datasets of midguts clustered at different temperatures (Fig. 2b). Overall, the expression profiles of the midgut transcripts changed in response to blood-feeding between the CT group and the infection groups (Fig. 2c), and the clustering of transcript profiles was affected by midgut breakthrough (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, we analyzed Pearson correlation coefficients among all the samples, and a heat map showed correlation values of paired samples between 0.75 and 1 (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the general transcriptome characteristics of Aedes albopictus. PCA1 and PCA2 accounted for 10.61% and 7.15% of the total variance in the dataset, respectively. Cluster analysis of transcriptome data from a single sample (a), samples at different temperatures (b), midgut datasets associated with viral treatment (c), and midgut breakthrough status (d). CT Control, MB midgut breakthrough, MNB midgut nonbreakthrough

Temperature alters Ae. albopictus transcriptomes during DENV-2 infection

DEGs between the CT and MB groups were analyzed at each temperature. There were 469 DEGs at 23 °C, 139 at 28 °C and 156 at 32 °C, and the same three upregulated and 10 downregulated genes at two of the temperatures (Fig. 3a). Compared to DEGs between the CT and MB groups, the transcriptomes between the CT and MNB groups were altered, with 180 DEGs at 23 °C, 90 at 28 °C and 140 at 32 °C, and the same three upregulated genes and four downregulated genes at two of the temperatures (Fig. 3b). Since temperature is an important factor that affects the midgut barrier, we analyzed the MB and MNB DEGs at different temperatures. Most DEGs were observed at 23 °C, followed by 28 °C, with the lowest number at 32 °C. There were no overlapping genes among the groups (Fig. 3c). The data show that the Ae. albopictus midgut transcriptomes change in response to temperature.

Venn diagram representation of the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified by RNA sequencing analysis in the midguts of Aedes albopictus. Number of DEGs between the CT and MB groups (a), CT and MNB groups (b), and MB and MNB groups (c) at different temperatures; d the MB and MNB groups compared to the CT group at 23 °C; e the MB and MNB groups compared to the CT group at 28 °C; f the MB and MNB groups compared to the CT group at 32 °C. For other abbreviations, see Fig. 2

In addition, the DEGs were different between the MB and MNB groups compared to the CT group at the same temperature. At 23 °C, there was a notable difference with 231 upregulated and 241 downregulated genes between the CT and MB groups, far more than between the CT and MNB groups (Fig. 3d). At 28 °C, the numbers of DEGs between the CT and MB groups were almost identical to those between the CT and MNB groups (Fig. 3e). At 32 °C, there were 45 upregulated and 82 downregulated genes between the CT and MB groups, and 33 upregulated and 46 downregulated genes between the CT and MNB groups (Fig. 3f). These results demonstrate that the Ae. albopictus midgut transcriptome is affected by the midgut barrier.

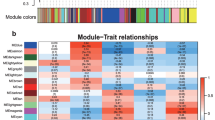

Key gene network associated with DENV-2 infection identified by WGCNA

To construct a WGCNA network, we first calculated the thresholding power to perform network topology analysis. The thresholding power was set at 4 in WGCNA because the scale independence reached 0.9 and showed suitable mean connectivity (Fig. 4a). Modules were determined using the WGCNA R package. The hierarchical cluster tree showed 28 modules of coexpressed genes (Fig. 4b), and the eigengene adjacency heat map indicated a relationship between pairwise gene modules (Fig. 4c). Correlations between modules and temperature and ingestion of DENV-2 blood meal were analyzed by WGCNA. According to the results, the ME3 module had the highest correlation with temperature, and the ME12 module was highly associated with the ingestion of a viral blood meal (Fig. 4d).

Weighted gene correlation network analysis revealing gene coexpression networks. a Analysis of network topology for various soft-thresholding powers. b The hierarchical cluster tree shows 28 modules of coexpressed genes. c The eigengene adjacency heat map indicates the relationship between the pairwise gene modules. d Correlations between modules and temperature. Each unit comprises the weight correlation coefficients and P-values. ME Module eigengene; for other abbreviations, see Fig. 2

Functional analysis of the key module associated with temperature

In this study, we focused on the pathway by which temperature affected the transmission of DENV-2 by Ae. albopictus. The ME3 module correlated with temperature was evaluated by GO and KEGG analyses. Unfortunately, no significant GO terms were enriched in this module (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). In the KEGG analysis, RNA degradation, Toll and immunodeficiency factor (IMD) signaling pathways and other pathways were enriched. Hence, our results show that these pathways are regulated by temperature (Fig. 5a). The genes involved in RNA degradation, Toll and IMD signaling pathways, nitrogen metabolism, fatty acid degradation and riboflavin metabolism are listed in Table 2 (Fig. 5b).

Validation of hub genes regulated by temperature

We selected eight genes related to the antiviral immunity of mosquitoes, as indicated by the literature, for validation. The expression levels of these genes were analyzed from RNA sequencing datasets (Fig. 6) and determined by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7). The expression trends of most samples were similar according to the RNA sequencing and qRT-PCR. The Kruskal–Wallis H-test demonstrated that “LOC109399943” annotated as “CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 6-like”, “LOC109418111” annotated as “protein PAT1 homolog 1” and “LOC109401240” annotated as “heat shock 70-kDa protein cognate 5” were significantly different in the samples overall. These hub genes regulated by temperature represent targets for dengue prevention.

Discussion

Model predictions and laboratory studies have shown that temperature affects the vector competence of Ae. albopictus for the transmission of DENV [16, 25]. However, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. In this study, RNA sequencing of the midguts of Ae. albopictus in the CT, MB and MNB groups was conducted, and the results revealed different transcriptional variations in response to DENV infection and temperature. WGCNA was used to identify key gene networks regulated by temperature. Then, we determined hub pathways associated with temperature.

In this research, we collected Ae. albopictus mosquitoes with different infection statuses. For the simultaneous collection of mosquitoes with and without midgut breakthrough at 23 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C, we determined the optical concentration of DENV-2 to be 8.625 log10 TCID50/mL based on preliminary experimental results, with a time to harvest of 7 days post-infection. The MIR and MBR of Ae. albopictus were increased following a rise in temperature. These results showed that higher temperature facilitated viral replication for midgut breakthrough. The trends of the results were consistent with those of previous experimental research and model predictions [16, 25, 26].

Previous research demonstrated that temperature affects Ae. aegypti gene expression after Zika virus infection [19]. In the present study, the expression profiles of the Ae. albopictus midgut clustered after the mosquito ingested a blood meal containing DENV-2. Furthermore, temperature affected midgut transcriptome clustering in Ae. albopictus of the MB and MNB groups, as low temperature resulted in more DEGs in these. To better understand the relationship between temperature and DENV-2 infection in Ae. albopictus, we used WGCNA, which has been proven to be an effective method for assessing gene coexpression networks and hub genes in tumors, plants and parasites, etc. [27,28,29,30,31]. In this study, the highest correlation with temperature was observed for the ME3 module.

The mosquito transcriptome changed in response to DENV, which might be related to the mosquito’s antiviral system. In contrast to the innate and adaptive immunity of humans to resist the invasion of pathogens, mosquitoes lack adaptive immunity and mainly rely on innate immunity to suppress viral proliferation. RNA interference, Toll, IMD, Janus kinase pathway signal transduction and activation and other pathways play important roles in mosquito antiviral immunity [32]. The gene expression profiles of mosquitoes infected with viruses were transformed following temperature change. In a previous study, Ae. aegypti infected with chikungunya virus were cultured at 18 °C, 28 °C and 32 °C; the Toll, IMD and Janus kinase pathway signal transduction and activation pathways were upregulated at 28 °C, and high temperature appeared to damage the mosquito’s immune defenses [33]. In our study, the pathways of the ME3 module regulated by temperature included RNA degradation, the Toll pathway and the IMD pathway.

DENV is an RNA virus, and the RNA degradation pathway is closely related to the proliferation of DENV in mosquitos [34]. Among the genes we identified, it has been shown that heat shock cognate 70 protein interacts with chikungunya virus to promote its entry into C6/36 cells [35], and 70-kDa heat shock cognate proteins have been identified as the most critical components in DENV-4 binding and entry into C6/36 cells [36]. Additionally, CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 6-like belongs to the CCR4-NOT complex family, which is involved in transcription, translation and messenger RNA decay [37]. The expression levels of CCR4-NOT complex genes were upregulated in DENV-infected cells, which is conducive to the proliferation of DENV [38]. In this study, the CCR4-NOT complex genes were highly expressed at 32 °C, which suggests that DENV-2 proliferated more quickly at 32 °C, which helped DENV-2 break through the midgut barrier.

Toll-like receptors are pattern recognition receptors that recognize mosquito-borne viruses and promote the maturation of Spätzle. The interaction between Toll-like receptors and Spätzle involves myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88), followed by the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B, which induces the release of nuclear antimicrobial peptides and other antiviral molecules [39]. Lower DENV-2 loads in mosquitoes from southern and western China may be related to the innate immunity of mosquitoes as affected by the Toll pathway [40]. Three proteins are regulated by temperature: modular serine protease, peptidoglycan-recognition protein and MyD88. MyD88 serves as the key mediator of Toll signaling. The inhibition of MyD88 significantly enhances the replication of DENV-2 in Ae. aegypti [41]. MyD88 is also involved in the antiviral immunity of Ae. aegypti against Japanese encephalitis virus [42]. We speculate that the MyD88 molecule is key to the virus’s ability to break through the midgut barrier.

Functional validation of the temperature regulation of the genes coding for these three proteins was not undertaken in the present study. Thus, in future work, we will produce the small (short) interfering RNA and double-stranded RNA of these genes to detect the proliferative ability of DENV-2 at the cell level and analyze the vector competence of Ae. albopictus to transmit DENV-2 at different temperatures.

Conclusions

To explore the mechanism through which temperature affects the transmission of DENV-2 by Ae. albopictus, we examined the variations in transcriptomes of its midgut at different temperatures using RNA sequencing. The altered genes identified here may be involved in viral resistance or viral infection, and Ae. albopictus may be more susceptible to DENV-2 when these genes are altered. Some important pathways, including the RNA degradation, Toll and IMD pathways, were identified by WGCNA and KEGG analysis as being regulated by temperature. This study provides experimental evidence applicable to the prevention and control of dengue.

Availability of data and materials

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Sequencing data were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession no. PRJNA772927.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Control

- DEG:

-

Differentially expressed gene

- DENV:

-

Dengue virus

- FPKM:

-

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- IMD:

-

Immunodeficiency factor

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MB:

-

Midgut breakthrough

- MBR:

-

Midgut breakthrough rate

- MIR:

-

Midgut infection rate

- MNB:

-

Midgut nonbreakthrough

- MNBR:

-

Midgut nonbreakthrough rate

- MyD88:

-

Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- TCID50 :

-

50% Tissue culture infective dose

- WGCNA:

-

Weighted gene correlation network analysis

References

Hamer DH. Dengue-perils and prevention. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2252–3.

Wilder-Smith A, Ooi EE, Horstick O, Wills B. Dengue. Lancet. 2019;393:350–63.

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–7.

Dos ST, Martin J, Castellanos LG, Espinal MA. Dengue in the Americas: Honduras’ worst outbreak. Lancet. 2019;394:2149.

Wilder-Smith A, Rupali P. Estimating the dengue burden in India. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e988–9.

Cousins S. Dengue rises in Bangladesh. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:138.

The Lancet. 2020: a crucial year for neglected tropical diseases. Lancet. 2019;394:2126.

Chen B, Liu Q. Dengue fever in China. Lancet. 2015;385:1621–2.

Zhao H, Zhang FC, Zhu Q, Wang J, Hong WX, Zhao LZ, et al. Epidemiological and virological characterizations of the 2014 dengue outbreak in Guangzhou, China. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e156548.

Guzman MG, Gubler DJ, Izquierdo A, Martinez E, Halstead SB. Dengue infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16055.

Liu B, Gao X, Ma J, Jiao Z, Xiao J, Hayat MA, et al. Modeling the present and future distribution of arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus under climate change scenarios in mainland China. Sci Total Environ. 2019;664:203–14.

Franklinos L, Jones KE, Redding DW, Abubakar I. The effect of global change on mosquito-borne disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e302–12.

Friedrich MJ. Global temperature affects dengue. JAMA. 2018;320:227.

Colon-Gonzalez FJ, Harris I, Osborn TJ, Steiner SBC, Peres CA, Hunter PR, et al. Limiting global-mean temperature increase to 1.5–2℃ could reduce the incidence and spatial spread of dengue fever in Latin America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:6243–8.

Carrington LB, Armijos MV, Lambrechts L, Scott TW. Fluctuations at a low mean temperature accelerate dengue virus transmission by Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2190.

Liu Z, Zhang Z, Lai Z, Zhou T, Jia Z, Gu J, et al. Temperature increase enhances Aedes albopictus competence to transmit dengue virus. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2337.

Franz AW, Kantor AM, Passarelli AL, Clem RJ. Tissue barriers to arbovirus infection in mosquitoes. Viruses. 2015;7:3741–67.

Kumar A, Srivastava P, Sirisena P, Dubey SK, Kumar R, Shrinet J, et al. Mosquito innate immunity. Insects. 2018;9:95.

Ferreira PG, Tesla B, Horacio E, Nahum LA, Brindley MA, de Oliveira MT, et al. Temperature dramatically shapes mosquito gene expression with consequences for mosquito-Zika virus interactions. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:901.

Ramakrishnan MA. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J Virol. 2016;5:85–6.

Lanciotti RS, Calisher CH, Gubler DJ, Chang GJ, Vorndam AV. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples by using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:545–51.

Frazee AC, Pertea G, Jaffe AE, Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Leek JT. Ballgown bridges the gap between transcriptome assembly and expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:243–6.

Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:559.

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–7.

Xu L, Stige LC, Chan KS, Zhou J, Yang J, Sang S, et al. Climate variation drives dengue dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:113–8.

Huber JH, Childs ML, Caldwell JM, Mordecai EA. Seasonal temperature variation influences climate suitability for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e6451.

Stuart JM, Segal E, Koller D, Kim SK. A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science. 2003;302:249–55.

Zhang B, Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2005;4:e17.

Jia R, Zhao H, Jia M. Identification of co-expression modules and potential biomarkers of breast cancer by WGCNA. Gene. 2020;750:144757.

Feng X, Zhu L, Qin Z, Mo X, Hao Y, Jiang Y, et al. Temporal transcriptome change of Oncomelania hupensis revealed by Schistosoma japonicum invasion. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:58.

El-Sharkawy I, Liang D, Xu K. Transcriptome analysis of an apple (Malus × domestica) yellow fruit somatic mutation identifies a gene network module highly associated with anthocyanin and epigenetic regulation. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:7359–76.

Liu T, Xu Y, Wang X, Gu J, Yan G, Chen XG. Antiviral systems in vector mosquitoes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2018;83:34–43.

Wimalasiri-Yapa B, Barrero RA, Stassen L, Hafner LM, McGraw EA, Pyke AT, et al. Temperature modulates immune gene expression in mosquitoes during arbovirus infection. Open Biol. 2021;11:200246.

Thomas S, Verma J, Woolfit M, O’Neill SL. Wolbachia-mediated virus blocking in mosquito cells is dependent on XRN1-mediated viral RNA degradation and influenced by viral replication rate. Plos Pathog. 2018;14:e1006879.

Ghosh A, Desai A, Ravi V, Narayanappa G, Tyagi BK. Chikungunya virus interacts with heat shock cognate 70 protein to facilitate its entry into mosquito cell line. Intervirology. 2017;60:247–62.

Vega-Almeida TO, Salas-Benito M, De Nova-Ocampo MA, Del AR, Salas-Benito JS. Surface proteins of C6/36 cells involved in dengue virus 4 binding and entry. Arch Virol. 2013;158:1189–207.

Denis CL, Chen J. The CCR4-NOT complex plays diverse roles in mRNA metabolism. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2003;73:221–50.

Liu J, Yang L, Liu F, Li H, Tang W, Tong X, et al. CNOT2 facilitates dengue virus infection via negatively modulating IFN-independent non-canonical JAK/STAT pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;515:403–9.

Cheng G, Liu Y, Wang P, Xiao X. Mosquito defense strategies against viral infection. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:177–86.

Wei Y, Wang J, Wei YH, Song Z, Hu K, Chen Y, et al. Vector competence for DENV-2 among Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) populations in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:649975.

Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti Toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PloS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000098.

Sasaki T, Kuwata R, Hoshino K, Isawa H, Sawabe K, Kobayashi M. Argonaute 2 suppresses Japanese encephalitis virus infection in Aedes aegypti. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2017;70:38–44.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 82002157, 82060379 and 81660345), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu of China (no. BK20180994), the Fund for Postdoctoral Research in China (no. 2018M632382), and the Hainan Natural Science Foundation (820RC653).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZZL and YX designed the study. ZZL wrote the manuscript. ZZL and YDL collected the mosquito samples. YX, SHX, YJL and CH analyzed the data. LX, XGC and KYZ contributed reagents for the study and revised the initial manuscript draft. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

The Pearson correlation coefficient of each sample was analyzed by heatmap.

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

The ME3 module correlating with temperature was evaluated by GO analyses.

Additional file 3: Table S1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Xu, Y., Li, Y. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Aedes albopictus midguts infected by dengue virus identifies a gene network module highly associated with temperature. Parasites Vectors 15, 173 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05282-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05282-y