Abstract

Background

Environmental disturbance, deforestation and socioeconomic factors all affect malaria incidence in tropical and subtropical endemic areas. Deforestation is the major driver of habitat loss and fragmentation, which frequently leads to shifts in the composition, abundance and spatial distribution of vector species. The goals of the present study were to: (i) identify anophelines found naturally infected with Plasmodium; (ii) measure the effects of landscape on the number of Nyssorhynchus darlingi, presence of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae, human biting rate (HBR) and malaria cases; and (iii) determine the frequency and peak biting time of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes and Ny. darlingi.

Methods

Anopheline mosquitoes were collected in peridomestic and forest edge habitats in seven municipalities in four Amazon Brazilian states. Females were identified to species and tested for Plasmodium by real-time PCR. Negative binomial regression was used to measure any association between deforestation and number of Ny. darlingi, number of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae, HBR and malaria. Peak biting time of Ny. darlingi and Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae were determined in the 12-h collections. Binomial logistic regression measured the association between presence of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae and landscape metrics and malaria cases.

Results

Ninety-one females of Ny. darlingi, Ny. rangeli, Ny. benarrochi B and Ny. konderi B were found to be infected with Plasmodium. Analysis showed that the number of malaria cases and the number of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae were more prevalent in sites with higher edge density and intermediate forest cover (30–70%). The distance of the drainage network to a dwelling was inversely correlated to malaria risk. The peak biting time of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae was 00:00–03:00 h. The presence of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes was higher in landscapes with > 13 malaria cases.

Conclusions

Nyssorhynchus darlingi, Ny. rangeli, Ny. benarrochi B and Ny. konderi B can be involved in malaria transmission in rural settlements. The highest fraction of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae was caught from midnight to 03:00 h. In some Amazonian localities, the highest exposure to infectious bites occurs when residents are sleeping, but transmission can occur throughout the night. Forest fragmentation favors increases in both malaria and the occurrence of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes in peridomestic habitat. The use of insecticide-impregnated mosquito nets can decrease human exposure to infectious Anophelinae and malaria transmission.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human malaria is mainly caused by the protozoan parasites Plasmodium falciparum Welch, 1897 and P. vivax (Grassi & Feletti, 1890). Four additional species have also been identified [1]. Approximately 70 species of the subfamily Anophelinae Grassi, 1900 are vectors of Plasmodium Marchiafava & Celli (1885), of which 41 are considered to be dominant vectors [2, 3]. In Brazil, Nyssorhynchus darlingi (Root, 1926; formerly Anopheles darlingi), Ny. marajoara (Galvao & Damasceno, 1942; formerly Anopheles marajoara) and Ny. aquasalis (Curry, 1932; formerly Anopheles aquasalis) are the primary vectors of human malaria [4, 5].

Despite major progress in the global control and elimination of malaria, the World Health Organization reports show alarming increases in the incidence of malaria from 2014 to 2018. In Brazil, after a 6-year period of successive reduction, the incidence of malaria increased from 117,832 cases in 2016 to 174,522 in 2017 [6]. A reduction of 19% in malaria incidence was reported from 2018 (193,837) to 2019 (156,918) [7]. Most cases (99.5%) occurred in the Amazon, with > 90% of infections caused by P. vivax. Malaria hotspots occurr in the Brazilian Amazon where both P. vivax and P. falciparum transmission is continuously high [8]. Such hotspots represent a challenge in terms of achieving the control and elimination of Plasmodium infection [9]. Some of these hotspots are found in the westernmost municipalities of Cruzeiro do Sul and Mâncio Lima (Acre state), where the proportion of malaria cases due to P. falciparum and P. vivax + P. falciparum can be as high as 25% of the overall estimated cases in Acre [7].

Environmental factors, including temperature, precipitation and humidity, can affect the risk of malaria infection [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Minor variations in temperature can increase or decrease the extrinsic incubation period of Plasmodium, which in turn affects the vector competence and vectorial capacity of populations of a vector species [16]. In addition, increased density of mosquito habitats in human-dominated landscapes can lead to augmented abundance of mosquito vectors, resulting in increased malaria incidence. An interrelated chain of ecological events has been shown to lead to alterations in mosquito species composition in environments that are impacted by habitat loss and fragmentation associated with anthropogenic activities [17, 18]. An increased abundance of generalist and opportunistic species [19], including vectors and infectious pathogens [20], has been shown to have a potential effect on mosquito communities. Also, changes in the spatiotemporal distribution of larval habitats can influence vector abundance and human–mosquito contact rate [21, 22]. Furthermore, changes in rural infrastructure that alter standing freshwater distribution, such as the construction of dams, reservoirs and irrigation networks, may increase malaria incidence unless they are coordinated with measures to minimize the risk of disease outbreaks [23]. In a study aimed to understand factors affecting the increase and decrease of malaria risk and the dynamics of transmission in areas that are currently experiencing ecological change and human occupation, Baeza et al. [24] demonstrated that the ecological changes that promote increases in mosquito abundance and Plasmodium dispersion occur at a faster rate than the socioeconomic factors that can prevent malaria transmission.

In the Amazon, deforestation is the major driver of changes in the forest landscape and also a major driver of increased malaria incidence [25]. However, the relationship between landscape change and malaria is complex and bidirectional, i.e. increased incidence of the disease in the early stages of deforestation can lead to a decrease in forest clearing [26]. Recently, Souza et al. [8] showed that the spatial pattern of malaria transmission linked to the economic expansion is primarily associated with extractive activities, human movement and agricultural settlements. In rural settlements, particularly those located in areas neighboring the forest fringe, environmental changes can increase the number of partially shaded larval habitats, thus favoring increased Ny. darlingi abundance [27]. In addition, socioeconomic factors impact malaria because poor housing, poor management of the environment and inadequate sanitary conditions facilitate human–mosquito contact and, thereby, can increase the human–mosquito contact rate and malaria transmission [28,29,30].

The dynamics of malaria are influenced by several factors linked to vector ecology, Plasmodium infection rate in both mosquito and human populations, human behavior and the environment. Malaria transmission in rural settlements affects the socioeconomic development, human well-being, quality of life and health of the communities, and is a major indicator of inequalities [31]. Consequently, field entomology investigations are of utmost importance in the search for an understanding of the factors that are permissive to the circulation of the infection and that challenge the success of control programs. The aim of this study was to assess how Ny. darlingi and other Anophelinae species contribute to malaria transmission in rural settlements in different forest clearing and fragmentation settings. Entomological field data and data on local malaria cases and landscape components were used to achieve the following aims: (i) identification of Plasmodium infection in anopheline species; (ii) measurement of the effects of landscape on the number of local malaria cases, the number of Ny. darlingi in peridomestic habitats, human biting rate (HBR) and number of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae in peridomestic habitats; and (iii) determination of the frequency and peak biting time of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes and Ny. darlingi.

Taking into account the malaria elimination policy in Brazil, we identified additional components that can present as challenges to vector control. For example, we found strong evidence of outdoor transmission of Plasmodium by Ny. darlingi and other anophelines. An interesting and yet intriguing result was that we detected P. falciparum in sylvatic anopheline species at the forest edges of Acre state. One of the novelties of this study was to show that the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of Plasmodium was greater after midnight, when the number of bites per human from Ny. darlingi was lower, in comparison with that in the crepuscular period.

Methods

Study area, mosquito collections and species identification

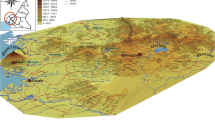

Mosquitoes of the subfamily Anophelinae were collected in rural settlements in the municipalities of Acrelândia (Acre state), Cruzeiro do Sul (Acre state), Mâncio Lima (Acre state), Itacoatiara (Amazonas state), Lábrea (Amazonas state), Pacajá (Pará state) and Machadinho D'Oeste (Rondônia state), Brazil (Fig. 1). These areas are characterized by a wet season, a dry season and wet–dry transition months. The mean annual regional rainfall is > 2000 mm, and the mean temperature is approximately 26 °C. The mean annual relative humidity is approximately 59% but varies substantially with rainfall and surface water [32].

Field collections were conducted from January 2015 to November 2016. In Acrelândia, Cruzeiro do Sul and Mâncio Lima, collections were conducted from 18:00 to 06:00 h, whereas in Machadinho D’Oeste, Rondônia, Pacajá, Pará, Itacoatiara and Lábrea, collections were conducted from 18:00 to 00:00 h (Table 1). Two data sets were employed for the statistical analyses. One data set comprised the 12-h collections and the second data set included the 6-h collections at all locations. Mosquitoes were sampled outdoors for 42 houses in 23 locations. In the peridomestic habitats, mosquitoes were collected using the human landing catch (HLC) and barrier screen sampling (BSS) methods. At the forest edge, mosquitoes resting on the walls of a Shannon trap (ST) were collected [33] using both a light source and human attraction. HLC and ST collections were carried out on one night at each of the 42 houses, whereas BSS collections were conducted in peridomestic habitats of 13 houses. The selection of field localities, houses in which HLC trapping was carried out and collection protocols are described in detail in Sallum et al. [32] and Massad et al. [34]. BSS was performed by two to four collectors in each of the 13 peridomestic habitats on the day after the HLC and ST collections (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Female mosquitoes were euthanized at hourly intervals with ethyl acetate (C4H8O2) vapors in the field and stored in silica gel; each set was marked with the date, location, house, collection method and hour of collection. All field collections were carried out under permanent permit number 12583–1 from the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio, SISBIO) granted to one of the authors (MAMS). The collection locations were not privately owned or protected, and the field studies did not involve protected or endangered species [35].

Specimens were identified to species level using the morphological key of Forattini [36], then labeled and stored individually in silica gel at room temperature for subsequent analysis. Specimens from species complexes were molecularly identified using a 658-bp fragment of the barcode region of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI) using the protocol described in Bourke et al. [37]. The taxonomic nomenclature adopted in this study is that proposed by Foster et al. [38].

Natural infectivity

Genomic DNA was extracted from all Anophelinae female mosquitoes using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Hilden, Germany). All DNA samples were tested for Plasmodium spp. infection as described by Sallum et al. [32]. DNA pools of up to five females containing equal amounts of genomic DNA (gDNA) were tested initially. Samples with a DNA concentration of < 1.0 ng/µl or > 15 ng/µl were tested individually and not pooled. Each real-time PCR was carried out in a final volume of 20 μl containing 1× PerfeCTa qPCR ToughMix, uracil N-glycosylase (UNG), ROX (Quanta BioSciences Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 0.3 μM each primer [39], ultrapure H2O and 2 μl of genomic DNA. The PCR thermal conditions were as follows: 5 min of UNG activation by holding at 45 °C; denaturation at 95 ºC/10 min, followed by amplification at 95 °C/15 s, 60 °C/1 min for 50 cycles. When the species of Plasmodium could not be detected with the triplex assay, conventional PCR was performed using primer pairs for P. vivax and P. falciparum [40].

Malaria cases

The numbers of malaria cases and human population at risk by epidemiological week and annual parasite incidence (API) for both P. vivax and P. falciparum were requested from the Ministry of Health, Sistemas de Informações de Vigilância Epidemiológica (SIVEP)-Malaria [41], through the Electronic System of the Citizen Information Service (Sistema Eletrônico do Serviço de Informações ao Cidadão [SIC]) (https://esic.cgu.gov.br/sistema/site/index.aspx), protocols #25,820,001,316,201,742, #25,820,003,892,201,813, #25,820,004,426,201,847 and #25,820,004,717,201,835) (Table 1).

Landscape analysis

Deforestation was measured as the amount of forest cover (FC), the sum of forest edges (i.e. a proxy for forest fragmentation, edge density [ED]) and the distance of the house from the drainage network (DW) in each location sampled. For each collection location, the percentage of FC in a 1-km radius (i.e. 3.14-km2 landscape) around the HLC house was calculated (see details in [32]). FC and other landscape metrics were calculated using European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel 2A satellite imagery from the closest possible date to the field collection, minimizing cloud coverage. Radiometric and atmospheric corrections were performed using ESA’s Sen2Cor software v2.4.0 [42]. Maximum likelihood supervised classification was used to assign each pixel as forest or non-forest using spectral bands 2, 3 and 4. The percentage FC was calculated for each collection site as described in Prussing et al. [35]. The ED is a measure of the total perimeter of the edge of each remaining fragment of forest present within the same area used to calculated percentage FC. The DW was built from digital elevation models (DEMs) available on the ESA website, as well as from the satellite images used for classification. Thus, through processes in a geographic information system (GIS) environment, it was possible to design the DW for the collection areas. The DW was used to calculate the distance from each HLC collection point to the nearest body of water. All landscape metrics were calculated from circular images of a 1-km radius centered on the house in which the HLC collection was performed. For each of the 42 locations, a circular image and the three above-mentioned metrics were obtained. There was no overlap between locations sampled.

Association between landscape, malaria cases and mosquitoes

Negative binomial regression as follows:

was used to estimate the association between each response variable: the number of local malaria cases, the number of Ny. darlingi in the peridomestic habitat, HBR and the number of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae in the peridomestic habitat and the independent variables FC, ED and DW.

As response variables: the number of Ny. darlingi corresponded to the sum of specimens collected by HLC from 18:00 to 00:00 h in each peridomestic habitat. The number of infected mosquitoes refers to the total of anophelines positive for Plasmodium spp. in each peridomestic habitat and collected by HLC from 18:00 to 00:00 h. Data on total local malaria cases of P. falciparum and P. vivax registered in each locality sampled in the previous month and the collection months were gathered from the national surveillance system (SIVEP) (Table 1). HBR was employed as a proxy for the HLC rate because we assumed that the females collected were seeking a blood meal. Therefore, HBR is the total of Ny. darlingi collected in each peridomestic habitat per night (18:00–00:00 h) by one person. The independent variables were grouped in categories as shown in Table 2.

The exponential of β represents the relative risk (IRR). We tested the following null hypothesis (H0: IRR = 1) with its alternative (Ha: IRR ≠ 1) considering a significance level of 0.05 (type-I error or α) and confidence intervals (CIs) of (1 − α)%. An IRR > 1 indicates a reciprocal association between the response and independent variables, whereas IRR < 1 indicates that this relationship was non-reciprocal. Lastly, IRR = 1 indicates no association (null effect).

Peak biting time

To determine the frequency and the peak biting time of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae and Ny. darlingi the negative binomial regression was used as follows:

where the response variables were number of Ny. darlingi and number of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae species. Data from 12-h collections in peridomestic habitats by HLC were used. The independent variable was the time interval (TI), stratified into quartiles. Each quartile corresponded to a 3-h time interval: first quartile, 18:00–21:00 h (baseline); second quartile, 21:00–00:00 h; third quartile, 00:00–03:00 h; and fourth quartile, 03:00–06:00 h. Analyses were performed by employing data from Acrelândia, Mâncio Lima and Cruzeiro do Sul, all in western Acre state, because 12-h collections were conducted only in these municipalities. We calculated the IRR and tested the hypothesis as described above.

Infected mosquitoes and landscape and malaria

Binomial logistic regression was applied to estimate the relationship between the presence of infected mosquitoes in peridomestic habitats and landscape metrics and local malaria cases. Explanatory variables are shown in Table 3. This model was adjusted by the number of local malaria cases, which was categorized based on median value. For this analysis, data from 39 peridomestic habitats were used, rather than 42, because anopheline mosquitoes were not found in three habitats. All analyses were performed using Stata/IC 16.1 software [43].

Results

Mosquito collection and species identification

A total of 6962 anophelines of 40 species (Additional file 2: Table S1) were collected in peridomestic and forest edge habitats in localities with active malaria transmission. The ST collections at the forest edge comprised 1492 anopheline mosquitoes. Peridomestic collections accounted for 5470 Anophelinae mosquitoes, of which 4369 were collected by HLC and 1101 by BSS. In the peridomestic habitats (Additional file 2: Table S1), 90.22% of the collected Anophelinae were Ny. darlingi, 2.03% were Ny. oryzalimnetes Wilkerson & Motoki, 2009 and 1.86% were Ny. braziliensis (Chagas, 1907). The remaining species accounted for 5.89% of the collection. In the forest edge, 27.35% were Ny. konderi B, 24.33% were Ny. triannulatus (s.l.) (Neiva & Pinto, 1922) and 21.45% were Ny. darlingi. The remaining Anophelinae species accounted for 26.87% of the collection. Thirteen specimens of the genus Chagasia Cruz, 1906 were collected at the forest edge but none were tested for Plasmodium.

Natural infectivity

A total of 6949 anopheline females were tested for Plasmodium infection, of which 69 were P. vivax positive, 20 were P. falciparum positive and two were P. vivax + P. falciparum positive (Table 4). The overall Plasmodium infection rate was 1.31%. Plasmodium vivax was identified in females collected in Mâncio Lima, Lábrea, Cruzeiro do Sul, Machadinho D’Oeste, Itacoatiara, Acrelândia and Pacajá, whereas Ny. darlingi infected with P. falciparum were collected in Mâncio Lima, Lábrea and Machadinho D’Oeste. Nyssorhynchus darlingi specimens with mixed P. vivax and P. falciparum infections were collected by HLC in a peridomestic habitat in Mâncio Lima. At the forest edge habitat, one Ny. darlingi collected in Lábrea, Amazonas state, was infected with P. falciparum and one Ny. konderi B from Acrelândia, Acre state had mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infections. Most Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes were collected by HLC (n = 72), 17 by BSS; two were caught in a ST (Table 4). The hourly distribution of Anophelinae-infected females in the peridomestic habitats of each municipaltiy is shown in Additional file 3: Figure S2 and Additional file 4: Figure S3.

Association between landscape, malaria cases and mosquitoes

The results of the negative binomial regression showed the following. First, the number of local malaria cases was positively associated with ED (Additional file 5: Table S2). The malaria IRR was 5.63-fold higher (IRR = 6.63, 95% CI 3.34—13.17, P < 0.001) in landscapes exposed to fragmentation (ED ranging from 0.0149 to 0.0292) than in those not exposed to fragmentation (ED ranging from 0.0077 to 0.0141). Secondly, the number of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes was positively associated with FC and negatively associated with DW (Additional file 6: Table S3). The IRR of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes was 2.99-fold higher (IRR = 3.99, 95% CI 1.08–14.79, P = 0.038) in moderately disturbed landscapes (FC ranging from 30 to 70%) than in both highly altered (FC ranging from 0 to 30%) and conserved landscapes (FC ranging from 70 to 100%). The IRR of collecting infected mosquitoes in peridomestic habitats ≤ 138 m distant from a DW was 0.22-fold higher (IRR = 0.22, 95% CI 0.06–0.76, p = 0.017) than that in habitats > 138 m distant from a DW. Thirdly, the number of Ny. darlingi and HBR had no association with any independent variable (P > 0.05).

Peak biting time

The regression analyses showed that the number of Ny. darlingi collected per hour decreased as the time approached 06:00 h, decreasing from 551 collected from 18:00–21:00 h, to 505 collected from 21:00–00:00 h, 313 collected from 00:00–03:00 h and 127 collected from 03:00–06:00 h. Using the data from 18:00–21:00 h as baseline, the lowest number of Ny. darlingi collected was from 03:00–06:00 h (IRR = 0.23, 95% CI 0.12–0.44, P < 0.001) (Additional file 7: Table S4).

In addition, the results also showed that the number of infected mosquitoes peaked (Table 5) after midnight, as opposed to the early evening peak abundance of collected Ny. darlingi. The IRR of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes was 600% greater in the overnight period (00:00–03:00 h) than during the time period when the peak number of Ny. darlingi were collected (18: 00–21:00 h) (IRR = 7.0, 95% CI 1.04–46.97, P = 0.045) (Table 5).

Infected mosquitoes, landscape and malaria

In Itacoatiara (Amazonas state), three peridomestic habitats were negative for Anophelinae and subsequently excluded from the binomial logistic regression analyses. The presence of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes in the peridomestic habitats was negatively associated with DW (odds ratio [OR] = 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.60, P = 0.013) and positively associated with the number of local malaria cases (OR = 9.41, 95% CI 1.49–59.65, P = 0.017) (Additional file 8: Table S5). No significant association was found with FC and ED. The OR of the presence of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes was 91% lower in sites nearest the DW (DW ≤ 138 m) than in sites more distant from the DW (DW > 138 m). The OR of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes in the peridomestic habitats was 8.41-fold higher in sites where the number of malaria cases was > 13 than in sites with ≤ 13 malaria cases.

Discussion

Anthropogenic change in natural environments is a major driver of deforestation, habitat fragmentation and ecological changes that usually favor the emergence, resurgence or proliferation of zoonotic pathogens, reservoir hosts and mosquito vectors [25, 44,45,46]. Changes in land use and freshwater distribution can lead to the increased abundance and dispersion of mosquito vectors and the propagation of the pathogens they can carry as intermediate reservoir hosts [23, 24]. In addition, poor socioeconomic conditions can increase human exposure to pathogens, thus causing surges in and spreading of vector-borne infections, including malaria [28].

The status of Ny. darlingi as a dominant vector of P. vivax and P. falciparum has been reinforced by the findings of this study carried out in rural settlements in the Brazilian Amazon basin. The importance of the exophilic population of Ny. darlingi in Amazonian Brazil is strengthened by the fact that one female collected in ST in the forest edge was infected with P. falciparum in Lábrea, Amazonas, and a second female infected by both P. vivax and P. falciparum was collected in a peridomestic site in Mâncio Lima. In nearby Amazonian Peru, Ny. darlingi collected in peridomestic sites using the HLC method have been detected to be infected with P. falciparum in numerous communities in the peri-Iquitos region and Mazan district [47,48,49].

The results of this investigation reveal that other species other than Ny. darlingi can be local vectors of Plasmodium in the rural settlements sampled. Specimens of Ny. rangeli and Ny. benarrochi B were found infected with P. vivax in peridomestic habitats, and Ny. konderi B collected in the forest edge was found to be infected by P. vivax and P. falciparum. The importance of Ny. benarrochi B as a local vector of P. vivax was shown by in an earlier investigation carried out in eastern Peru [50] and in Putumayo, Colombia [51]. In the present study, females of Ny. benarrochi B infected with P. vivax were captured in HLC in Pacajá, Pará state, suggesting a local role for this species in Plasmodium dispersion among settlers. Nyssorhynchus benarrochi is a species complex composed of Ny. benarrochi (s.s.), Ny. benarrochi B, Nyssorhynchus benarrochi G1 and Nyssorhynchus benarrochi G2 [37]. Whereas Ny. benarrochi (s.s.) was identified based on morphology only, the other three members of the complex were defined by DNA sequence data. Thus, further work is necessary to obtain further evidence to separate these species using both morphology and DNA data and to identify those species that are vectors of Plasmodium. According to Bourke et al. [37], Ny. benarrochi B is found in Cruzeiro do Sul, Mâncio Lima, western Acre state and Peru, Ny. benarrochi G1 occurs in Acrelândia, Acre state and Ny. benarrochi G2 occurs in Machadinho D’Oeste, Rondônia state. Nyssorhynchus rangeli is a local vector that usually occurs at low frequencies in endemic areas. Females infected with Plasmodium spp. have been reported in Amapá state [52], southern Colombia [53] and southern Peru [54], whereas in the present study, Ny. rangeli was found infected with P. vivax only in Acrelândia, Acre state. Nyssorhynchus konderi B belongs to the Oswaldoi-Konderi Complex [55]. Other species of this complex have been found naturally infected with Plasmodium infection, such as Ny. oswaldoi (s.l.) and Ny. konderi (s.l.) [52, 53, 56, 57]. In the present study, Plasmodium-infected Ny. konderi B was collected by ST at the forest edge in a location with approximately 84% forest cover, where Ny. konderi B was a dominant species (334 specimens of Ny. konderi B among 506 Culicidae collected).

The positive association between the number of local malaria cases and forest fragmentation, using ED as a proxy of fragmentation, and between the number of Plasmodium-infected anophelines and percentage of FC reinforce previous findings that forest clearing is a risk factor for malaria in Amazonian settlements [26, 58, 59]. Undisturbed areas of the Amazon forest do not provide favorable ecological and environmental conditions for the proliferation of Ny. darlingi [60]. In previous field collections carried out in reserves and undisturbed forest locations throughout Amazonas state, Ny. darlingi was either absent or rare [61,62,63,64], compared with sylvatic species of the Stethomyia, Lophopodomia and Chagasia genera of the subfamily Anophelinae. The loss and fragmentation of FC allow sunlight to reach the soil, leading to changes in freshwater conditions (e.g. in the temperature and pH, among other factors) and increasing the suitability of the larval habitat for Ny. darlingi [21, 60]. Together with local socioecological factors, a high density of vector species and high prevalence of infection in humans and in the vector populations, malaria transmission becomes endemic and sustainable [28]. Even though the conditions of many Amazonian rural settlements support malaria transmission, disease distribution remains heterogeneous. This uneven occurrence can be explained by rapid urbanization and improved socioeconomic conditions in consolidated settlements, whereas transmission is high in areas where the economic activity is linked to exploitation of forest products and agricultural settlements [8], associated with continuous deforestation [59]. The transmission intensity of P. vivax infection in some Amazonian rural settlements can be as high as that for P. falciparum in sub-Saharan Africa, whereas in other rural settlements the transmission is low [32, 34]. The risk of acquiring a vector-borne pathogen, including malaria linked to habitat fragmentation, decreases when the distribution of mosquitoes is proportional to that of humans [65].

The results of the analyses showed a negative association between the distance of the household to the nearest water DW and the presence and number of Plasmodium-infected anophelines in the peridomestic habitat, including Ny. darlingi. This finding indicates that residents of houses closer to a DW have a lower risk of being exposed to anopheline bites and Plasmodium-infected females—and contradicts previous findings that demonstrated that residents of houses closer to forest edges have a higher risk of acquiring malaria [58]. However, the DW is a landscape metric, not a proxy of the distance of a household from the forest edge. In addition, our findings can be understood in the context of the distribution of the primary larval habitat of Ny. darlingi in the sampled areas. Despite our lack of information on local larval habitat distribution, it is not uncommon to detect water redistribution linked to human land occupation for farming development and food production [23]. In rural areas of the Brazilian Amazon, freshwater redistribution has been found to increase the number of Ny. darlingi larval habitats and the density of this species in a human-dominated environment [21, 27]. Fish-farming ponds also result in the redistribution of freshwater and are associated with epidemic and endemic malaria transmission in urban, periurban and rural areas in western Amazonia [66, 67], Peruvian Amazon [68] and western Kenya [69]. Both commercial and non-commercial pisciculture, particularly when either abandoned or situated at the edge of vegetation that is not cleared constantly, lead to higher mosquito abundance, including malaria vector species [35, 66, 67].

Heterogeneous biting behavior of Ny. darlingi in terms of blood-feeding inside and outside houses and variations in the peak time of biting have been shown by numerous studies carried out across the Amazon [60]. Although along the Napo River in Mazán District, Peru, Ny. darlingi bites outdoors more frequently than indoors [49], in San José de Lupuna and Cahuide in peri-Iquitos state, Peru, the mosquito showed a trend of increased feeding inside houses, but only after the repellent effects of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets were presumed to have worn off [48]. In addition, variation in biting behavior was reported in French Guiana, where Ny. darlingi peaks between 20:30 and 22:30 h [70], and in Venezuela, this mosquito bites throughout the night, with minor peaks at 23:00–00:00 h and 03:00–04:00 h [71]. In the northeastern Amazon, in Macapá municipality, Amapá state, Ny. darlingi was detected with either a low but continuous biting peak [72] or multimodal biting peaks throughout the night [73]. Changes in biting behavior of Ny. darlingi can be associated with deforestation, ecological factors and microclimate conditions, which emerge due to changes in temperature and humidity. In Iquitos, Peruvian Amazon, the biting rate of this vector species was found to be significantly higher in a region that was undergoing massive deforestation associated with road construction than in locations where the forest remained mostly undisturbed [74].

In the present study, the 12-h HLC collections revealed that the peak time of biting of Plasmodium-infected Anophelinae was from 00:00 to 03:00 h in Mâncio Lima, Acrelândia and Cruzeiro do Sul, Acre state. In these regions, although infected mosquitoes were collected throughout the 12-h collections, 73% of the infected mosquitoes (30/41) were captured between 00:00 and 06:00 h. Results of previous studies have shown that the frequency of nulliparous females was higher from 18:00 to 22:00 h, whereas parous females were more frequently collected from 02:00 to 06:00 h [75]. With respect to the latter, the likelihood of collecting infected females in our study should be higher in the second period. The peak biting time of Plasmodium-infected females may also be linked to a daily rhythmic behavior that protects females from desiccation by flying at night, increases female longevity and increases biting success and capacity to transmit sporozoites to susceptible hosts at a time when they are less defensive [76]. An experimental study employing P. chabaudi genotype AS parasites and Anopheles stephensi showed that the interaction between increased gametocyte infectiousness at night and increased mosquito susceptibility to infection enhanced parasite transmission [77]. A similar adaptive periodicity and protective behavior from high temperature/low humidity may occur in mosquitoes that are involved in Plasmodium transmission to humans.

The results of this study underscore the importance of the dominant malaria vector, Ny. darlingi, and other vector species of human Plasmodium in the Brazilian Amazon. The involvement of several Anophelinae species in the dynamics of the Plasmodium spp. transmission cycle adds complexity to parasite–vector associations, with implications for an effective malaria control in a region that being impacted by extensive anthropogenic disturbances in the forest environment. The delineation of interventions for malaria control in a heterogeneous scenario of transmission that involves distinct species will require continuous investigation, primarily to verify the role of each species in transmission. Investigations focusing on the knowledge of field malariology are required to define the local determinants of malaria transmission, as denoted by Baird [78] and Benelli and Beier [79]. Ecological characteristics, such as variation in mosquito behavior, vector biodiversity, lack of knowledge of the impact of environmental change on mosquito ecology, among others, can impede the success of malaria control and elimination programs [79].

Conclusions

Nyssorhynchus benarrochi B and Ny. konderi B were found to be naturally infected with Plasmodium, and our results corroborate the importance of Ny. rangeli as a secondary vector of Plasmodium, adding complexity to a program targeting the control of multiple vectors. Forest fragmentation favored an increase in malaria occurrence. The likelihood of being exposed to Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes in the peridomestic environment is lower in households situated closer to a drainage network than in more distantly located houses. The early hours of the morning were found to present greater risk for being bitten by an infected female in the settlements studied. Thus, the findings of this study provide novel ecological knowledge about anopheline vectors of Plasmodium in rural settlements in the Amazon basin and reinforce the importance of the use of impregnated mosquito nets and screens in windows and doors. Further studies should be carried out to verify if the period of higher biting activity described here is also found in landscapes of other rural settlements and to determine the factors contributing to this pattern.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in the manuscript will be freely available to any scientist wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes upon request to the corresponding author. In addition, the full data will be publicly available after publication of a series of articles in preparation.

Abbreviations

- API:

-

Annual parasite incidence

- BSS:

-

Barrier screen sampling

- COI:

-

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene

- C4H8O2 :

-

Ethyl acetate

- DEM:

-

Digital elevation model

- DW:

-

Drainage network

- ED:

-

Edge density

- ESA:

-

European Space Agency

- FC:

-

Forest cover

- GIS:

-

Geographic information system

- GML:

-

Generalized linear model

- HBR:

-

Human biting rate

- HLC:

-

Human landing catch

- ICMBio:

-

Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade

- IRR:

-

Incidence ratio rate

- SIC:

-

Serviço de Informações ao Cidadão

- SIVEP:

-

Sistemas de Informações de Vigilância Epidemiológica

- ST:

-

Shannon trap

References

Milner DA Jr. Malaria pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(1):a025569. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a025569.

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Rubio-Palis Y, Chareonviriyaphap T, Coetzee M, et al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit Vect. 2012;5:69.

Molina-Cruz A, Zilversmit MM, Neafsey DE, Hartl DL, Barrilas-Mury C. Mosquito vectors and the globalization of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Annu Rev Genet. 2016;50:447–65.

Carlos BC, Rona LD, Christophides GK, Souza-Neto JA. A comprehensive analysis of malaria transmission in Brazil. Pathog Glob Health. 2019;113:1–13.

Baia-da-Silva DC, Brito-Sousa JD, Rodovalho SR, Peterka C, Moresco G, Lapouble OMM, et al. Current vector control challenges in the fight against malaria in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;52:e20180542. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0542-2018.

Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Epidemiological alert. Increase of malaria in the Americas. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2017/2017-feb-15-phe-epi-alert-malaria.pdf (2018). Accessed 17 Feb 2020.

Ministério da Saúde–MS. Dados para o cidadão, Sivep-Malária. https://public.tableau.com/profile/mal.ria.brasil#!/. Accessed 28 Oct 2020.

Souza PF, Xavier DR, Suarez Mutis MC, da Mota JC, Peiter PC, de Matos VP, et al. Spatial spread of malaria and economic frontier expansion in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0217615.

Stresman G, Bousema T, Cook J. Malaria hotspots: Is there epidemiological evidence for fine-scale spatial targeting of interventions? Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:822–34.

Rossati A, Bargiacchi O, Kroumova V, Zaramella M, Caputo A, Garavelli PL. Climate, environment and transmission of malaria. Infez Med. 2016;24:93–104.

Cella W, Baia-da-Silva DC, Melo GC, Tadei WP, Sampaio VS, Pimenta P, et al. Do climate changes alter the distribution and transmission of malaria? Evidence assessment and recommendations for future studies. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;52:e20190308.

Diouf I, Fonseca BR, Caminade C, Thiaw WM, Deme A, Morse AP, et al. Climate variability and malaria over West Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(5):1037–47.

Amadi JA, Olago DO, Ong’amo GO, Oriaso SO, Nanyingi M, Nyamongo IK, et al. Sensitivity of vegetation to climate variability and its implications for malaria risk in Baringo, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7):e0199357.

Matthew OJ. Investigating climate suitability conditions for malaria transmission and impacts of climate variability on mosquito survival in the humid tropical region: a case study of Obafemi Awolowo University Campus, Ile-Ife, south-western Nigeria. Int J Biometeorol. 2020;64:355–65.

Coutinho PEG, Candido LA, Tadei WP, da Silva Junior UL, Correa HKM. An analysis of the influence of the local effects of climatic and hydrological factors affecting new malaria cases in riverine areas along the Rio Negro and surrounding Puraquequara Lake, Amazonas, Brazil. Environ Monit Assess. 2018;190(5):311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-6677-4.

Thomas S, Ravishankaran S, Justin NAJA, Asokan A, Kalsingh TMJ, Mathai MT, et al. Microclimate variables of the ambient environment deliver the actual estimates of the extrinsic incubation period of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum: a study from a malaria endemic urban setting Chennai in India. Malar J. 2018;17:201.

Burkett-Cadena ND, Vittor AY. Deforestation and vector-borne disease: forest conversion favors important mosquito vectors of human pathogens. Basic Appl Ecol. 2018;26:101–10.

Multini LC, Souza ANS, Marrelli MT, Wilke ABB. The infuence of anthropogenic habitat fragmentation on the genetic structure and diversity of the malaria vector Anopheles cruzii (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci Rep. 2020;10:18018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74152-3.

Hernández-Valencia JC, Rincón DS, Marín A, Naranjo-Díaz N, Correa MM. Effect of land cover and landscape fragmentation on anopheline mosquito abundance and diversity in an important Colombian malaria endemic region. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0240207.

Wilke ABB, Vasquez C, Medina J, Carvajal A, Petrie W, Beier JC. Community composition and year-round abundance of vector species of mosquitoes make MiamiDade county, Florida a receptive gateway for arbovirus entry to the United States. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8732. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45337-2.

Rufalco-Moutinho P, Schweigmann N, Bergamaschi DP, Sallum MAM. Larval habitats of Anopheles species in a rural settlement on the malaria frontier of southwest Amazon. Brazil Acta Trop. 2016;164:243–58.

Sánchez-Ribas J, Oliveira-Ferreira J, Gimnig JE, Pereira-Ribeiro C, Santos-Neves MSA, Silva-do-Nascimento TF. Environmental variables associated with anopheline larvae distribution and abundance in Yanomami villages within unaltered areas of the Brazilian Amazon. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:571. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2517-6.

Rohr JR, Barrett CB, Civitello DJ, Craft ME, Delius B, DeLeo GA, et al. Emerging human infectious diseases and the links to global food production. Nat Sustain. 2019;2:445–56.

Baeza A, Santos-Vega M, Dobson AP, Pascual M. The rise and fall of malaria under land-use change in frontier regions. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1:108.

Castro MC, Baeza A, Codeço CT, Cucunubá ZM, Dal’Asta AP, De Leo GA, et al. Development, environmental degradation, and disease spread in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000526.

MacDonald AJ, Mordecai EA. Amazon deforestation drives malaria transmission, and malaria burden reduces forest clearing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:22212–8.

Arcos AN, Ferreira FAS, Cunha HB, Tadei WP. Characterization of artificial larval habitats of Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Brazilian Central Amazon. Rev Bras Entomol. 2018;62:267–74.

Cohen JM, Menach AL, Pothin E, Eisele TP, Gething PW, Eckhoff PA, Moonen B, Schapira A, Smith SL. Mapping multiple components of malaria risk for improved targeting of elimination interventions. Malar J. 2017;16:459.

Corder RM, Paula GA, Pincelli A, Ferreira MU. Statistical modeling of surveillance data to identify correlates of urban malaria risk: a population-based study in the Amazon Basin. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220980. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220980.

Rek JC, Alegana V, Arinaitwe E, Cameron E, Kamya MR, Katureebe A, et al. Rapid improvements to rural Ugandan housing and their association with malaria from intense to reduced transmission: a cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30010-X.

Canelas T, Castillo-Salgado C, Baquero OS, Ribeiro H. Environmental and socioeconomic analysis of malaria transmission in the Brazilian Amazon, 2010–2015. Rev Saúde Pública. 2019;53:49. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2019053000983.

Sallum MAM, Conn JE, Bergo ES, Laporta GZ, Chaves LSM, Bickersmith SA, . Vector competence, vectorial capacity of Nyssorhynchus darlingi and the basic reproduction number of Plasmodium vivax in agricultural settlements in the Amazonian Region of Brazil. Malar J. 2019;18:117.

Shannon R. Methods for collecting and feeding mosquitos in jungle yellow fever studies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1939;19:131–48.

Massad E, Laporta GZ, Conn JE, Chaves LS, Bergo ES, Guimarães Figueira EA, . The risk of malaria infection for travelers visiting the Brazilian Amazonian region: a mathematical modeling approach. Travel Med Infect Di. 2020;37:101792.

Prussing C, Emerson KJ, Bickersmith SA, Sallum MAM, Conn JE. Minimal genetic differentiation of the malaria vector Nyssorhynchus darlingi associated with forest cover level in Amazonian Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225005.

Forattini OP. Culicidologia médica: Identificação, biologia, epidemiologia. First edition. São Paulo: Ed. USP. 2002.

Bourke BP, Conn JE, Oliveira TMP, Chaves LSM, Bergo ES, Laporta GZ, et al. Exploring malaria vector diversity on the Amazon frontier. Malar J. 2018;17:342.

Foster PG, Oliveira TMP, Bergo ES, Conn JE, Sant’Anna DC, Nagaki SS, et al. Phylogeny of Anophelinae using mitochondrial protein coding genes. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:170758.

Bickersmith AS, Lainhart W, Moreno M, Chu VM, Vinetz JM, Conn JE. A sensitive, specific and reproducible real-time polymerase chain reaction method for detection of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infection in field-collected anophelines. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:573–6.

Laporta GZ, Burattini MN, Levy D, Fukuya LA, Oliveira TMP, Maselli LMF, et al. Plasmodium falciparum in the southeastern Atlantic forest: a challenge to the bromeliad-malaria paradigm? Malar J. 2015;14:181.

Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Datasus. SIVEP-Malária. Sistema Eletrônico do Serviço de Informações ao Cidadão (e-SIC). 2018. https://esic.cgu.gov.br/sistema/site/index.aspx

Mueller-Wilm U, Devignot O, Pessiot L. Sen2Cor. European Space Agency. https://step.esa.int/main/third-party-plugins-2/sen2cor/. 2017.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: release 16. College Station: StataCorp LLC. 2019.

Geoghegan JL, Holmes EC. Predicting virus emergence amid evolutionary noise. Open Biol. 2017;7:170189.

Plowright RK, Parrish CR, McCallum H, Hudson PJ, Ko AI, Graham AL, et al. Pathways to zoonotic spillover. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:502–10.

Tran A, L’Ambert G, Balança G, Pradier S, Grosbois V, Balenghien T, et al. An integrative eco-epidemiological analysis of West Nile Virus transmission. EcoHealth. 2017;14:474–89.

Moreno M, Saavedra MP, Bickersmith SA, Prussing C, Michalski A, Tong Rios C, et al. Intensive trapping of blood-fed Anopheles darlingi in Amazonian Peru reveals unexpectedly high proportions of avian blood-meals. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005337.

Prussing C, Moreno M, Saavedra MP, Bickersmith SA, Gamboa D, Alava F, et al. Decreasing proportion of Anopheles darlingi biting outdoors between long-lasting insecticidal net distributions in peri-Iquitos, Amazonian Peru. Malar J. 2018;17(1):86.

Saavedra MP, Conn JE, Alava F, Carrasco-Escobar G, Prussing C, Bickersmith SA, et al. Higher risk of malaria transmission outdoors than indoors by Nyssorhynchus darlingi in riverine communities in the Peruvian Amazon. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12:374.

Flores-Mendonza C, Fernández R, Escobedo-Vargas KS, Vela-Perez Q, Schoeler GB. Natural Plasmodium infections in Anopheles darlingi and Anopheles benarrochi (Diptera: Culicidae) from Eastern Peru. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:489–94.

Orjuela LI, Herrera M, Erazo H, Quiñones ML. Especies de Anopheles presentes en el departamento del Putumayo y su infección natural con Plasmodium. Biomedica. 2013;33:42–52.

Póvoa MM, Wirtz RA, Lacerda RNL, Miles MA, Warhurst D. Malaria vectors in the municipality of Serra do Navio, State of Amapá, Amazon region. Brazil Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:179–84.

Quiñones ML, Ruiz F, Calle DA, Harbach RE, Erazo HF, Linton Y-M. Incrimination of Anopheles (Nyssorhynchus) rangeli and An. (Nys.) oswaldoi as natural vectors of Plasmodium vivax in Southern Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:617–23.

Conn JE, Norris DE, Donnelly MJ, Beebe NW, Burkot TR, Coulibaly MB, et al. Entomological monitoring and evaluation: diverse transmission settings of ICEMR projects will require local and regional malaria elimination strategies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:28–41.

Ruiz-Lopez F, Wilkerson RC, Ponsonby DJ, Herrera M, Sallum MAM, Velez ID, et al. Systematics of the oswaldoi complex (Anopheles, Nyssorhynchus) in South America. Parasites Vectors. 2013;6:324.

Branquinho MS, Lagos CBT, Rocha RM, Natal D, Barata JMS, Cochrane AH, et al. Anophelines in the state of Acre, Brazil, infected with Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, the variant P. vivax VK247 and P. malariae. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:391–4.

Branquinho MS, Araújo MS, Natal D, Marrelli MT, Rocha RM, Taveira FAL, et al. Anopheles oswaldoi a potencial malaria vector in Acre, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:233.

da Silva-Nunes M, Codeço CT, Malafronte RS, da Silva NS, Juncansen C, Muniz PT, et al. Malaria on the Amazonian frontier: transmission dynamics, risk factors, spatial distribution, and prospects for control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:624–35.

Chaves LSM, Conn JE, López RVM, Sallum MAM. Abundance of impacted forest patches less than 5 km2 is a key driver of the incidence of malaria in Amazonian Brazil. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7077.

Hiwat H, Bretas G. Ecology of Anopheles darlingi Root with respect to vector importance: a review. Parasites Vectors. 2011;4:177.

Hutchings RS, Sallum MA, Ferreira RL, Hutchings RW. Mosquitoes of the Jaú National Park and their potential importance in Brazilian Amazonia. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:428–41.

Hutchings RSG, Hutchings RW, Menezes IS, Motta MA, Sallum MAM. Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from the Northwestern Brazilian Amazon: Padauari River. J Med Entomol. 2016;53:1330–47.

Hutchings RSG, Hutchings RW, Menezes IS, Motta MA, Sallum MAM. Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from the Northwestern Brazilian Amazon: Araçá River. J Med Entomol. 2018;55:1188–209.

Hutchings RSG, Hutchings RW, Menezes IS, Sallum MAM. Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) From the Southwestern Brazilian amazon: Liberdade and Gregório Rivers. J Med Entomol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjaa100.

Gao D, van den Drissche P, Cosner C. Habitat fragmentation promotes malaria persistence. J Math Biol. 2019;67:2255–80.

dos Reis IC, Codeço CT, Degener CM, Keppeler EC, Muniz MM, Oliveira FGS, et al. Contribution of fish farming ponds to the production of immature Anopheles spp. in a malaria-endemic Amazonian town. Malar J. 2015;14:452.

Reis IC, Honório NA, Barros FS, Barcellos C, Kitron U, Camara DC, et al. Epidemic and endemic malaria transmission related to fish farming ponds in the Amazon Frontier. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137521.

Maheu-Giroux M, Casapía M, Soto-Calle VE, Ford LB, Buckeridge DL, Coomes OT, et al. Risk of malaria transmission from fishponds in the Peruvian Amazon. Acta Trop. 2010;115:112–8.

Howard AF, Omlin FX. Abandoning small-scale fish farming in western Kenya leads to higher malaria vector abundance. Acta Trop. 2008;105:67–73.

Vezenegho SB, Adde A, de Pommier Santi V, Issaly J, Carinci R, Gaborit P, et al. High malaria transmission in a forested malaria focus in French Guiana: how can exophagic Anopheles darlingi thwart vector control and prevention measures? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111:561–9.

Moreno JE, Rubio-Palis Y, Páez E, Pérez E, Sánchez V. Abundance, biting behaviour and parous rate of anopheline mosquito species in relation to malaria incidence in gold-mining areas of southern Venezuela. Med Vet Entomol. 2007;21:339–49.

Zimmerman RH, Lounibos LP, Nishimur AN, Galardo AKR, Galardo CD, Arruda ME. Nightly biting cycles of malaria vectors in a heterogeneous transmission area of eastern Amazonian Brazil. Malar J. 2013;12:262.

Barbosa LMC, Souto RNP, Dos Anjos Ferreira RM, Scarpassa VM. Behavioral patterns, parity rate and natural infection analysis in anopheline species involved in the transmission of malaria in the northeastern Brazilian Amazon region. Acta Trop. 2016;164:216–25.

Vittor AY, Gilman RH, Tielsch J, Glass G, Shields T, Lozano WS, et al. The effect of deforestation on the human-biting rate of Anopheles darlingi, the primary vector of Falciparum Malaria in the Peruvian Amazon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:3–11.

Barros FSM, Arruda ME, Vasconcelos SD, Luitgards-Moura JF, Confalonieri U, Rosa-Freitas MG, et al. Parity and age composition for Anopheles darlingi Root (Diptera: Culicidae) and Anopheles albitarsis Lynch-Arribálzaga (Diptera: Culicidae) of the northern Amazon Basin. Brazil J Vect Ecol. 2007;32:54–68.

Rund SS, O’Donnell AJ, Gentile JE, Reece SE. Daily rhythms in mosquitoes and their consequences for malaria transmission. Insects. 2016;7(2):14.

Schneider P, Rund SSC, Smith NL, Prior KF, O’Donnell AJ, Reece SE. Adaptive periodicity in the infectivity of malaria gametocytes to mosquitoes. Proc Biol Sci. 1888;2018(285):20181876.

Baird JK. Asia-Pacific malaria is singular, pervasive, diverse and invisible. Int J Parasitol. 2017;47:371–7.

Benelli G, Beier J. Current vector control challenges in the fight against malaria. Acta Trop. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.06.028.

Ministério da Saúde. Guia para o planejamento das ações de captura de anofelinos pela técnica de atração por humano protegido (TAHP) e acompanhamento dos riscos à saúde do profissional capturador. https://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=https-3A__bvsms.saude.gov.br_bvs_publicacoes_guia-5Fplanejamento-5Facoes-5Fcaptura-5Fanofelinos-5Ftecnica-5Fatracao-5Fhumano-5Fprotegido.pdf&d=DwIGaQ&c=vh6FgFnduejNhPPD0fl_yRaSfZy8CWbWnIf4XJhSqx8&r=LGl9Hene6XU63t3qE6EBOE3m4WF4AqLWyPol8LeniCewJ5S-5MMlfHeDglIy7Ym1&m=TLOaNSz30tRLtwvyqsWnFXDH1szRjEsJmRz5JI-2XXs&s=n_R9bCkFnELrAvq4gYrUCbC0yqkvTEUQDzeuH4pgqdM&e=. 2019. Accessed 13 Apr 2021

Acknowledgements

MAMS is grateful to the staff of the municipalities responsible for malaria control for providing useful information that guided field collections in Cruzeiro do Sul, Mâncio Lima, Lábrea, Machadinho D’Oeste, Acrelândia, Pacajá and Itacoatiara. The authors greatly appreciate the cooperation of all inhabitants of the rural settlements, as well as of the staff of the Vector Malaria Control of the municipalities, who generously helped the authors contact the members of the communities where malaria is a trap for maintaining cycles of poverty, inequality and human suffering. Without their help this study would not have been possible.

Funding

This work has been funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo—FAPESP Grant No. 2014/26229–7 to MAMS and EM; Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa—CNPq no. 301877/2016–5 to MAMS; the National Institutes of Health, USA, Grant 2R01AI110112-06A1 to JEC; GZL is supported by FAPESP Grant No. 2014/09774–1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAMS, JEC, EM and GZL conceived of the study. TMPO and SB conducted real-time PCR identification of anopheline females. MAMS, ESB, GZL and LSMC planned and conducted the field collections, including the human landing catches. MAMS identified field specimens. TMPO conducted statistical tests with input by JLF, GZL and MAMS. TMPO, MAMS, EM, GZL and JEC wrote the manuscript, with valuable contributions from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol regarding the HLC was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of São Paulo in June 2014, approval number 159/14, Department of Legal Medicine, Medical Ethics, Social and Occupational Medicine of the College of Medicine. Mosquito collectors (MAMS, ESB, LSC and GZR) followed the recommendation from the Ministry of Health [80].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Figure S1.

Drawing illustrating the peridomestic and forest edge habitats where the barrier screen and Shannon trap mosquito collections were carried out.

Additional file 2. Table S1.

Species of the subfamily Anophelinae collected in peri-domestic and forest edge habitats in rural settlements across the Brazilian Amazon.

Additional file 3. Figure S2.

Hourly distribution and number of Anophelinae and Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes in 12 h collections in peridomestic habitat. Collections of 12 h were performed in Cruzeiro do Sul, Acrelândia and Mâncio Lima municipalities, Acre state, Brazil.

Additional file 4. Figure S3.

Hourly distribution and number of Anophelinae and Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes in 6-h collections in peridomestic habitat. Collections of 6 h were performed in Lábrea (Acre state), Itacoatiara (Amazonas state), Machadinho D’Oeste (Rondônia state), Pacajá (Pará state) municipalities, Brazil. Note differences in y-axis scales.

Additional file 5. Table S2.

Final model of the negative binomial regression analysis for the response variable: number of local malaria cases.

Additional file 6. Table S3.

Final multiple models of the negative binomial regression analysis for the response variable: number of infected mosquitoes.

Additional file 7. Table S4.

Negative binomial regression analysis. Number of Ny. darlingi in the different collection intervals.

Additional file 8. Table S5.

Final multiple models of the binomial logistic regression analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, T.M.P., Laporta, G.Z., Bergo, E.S. et al. Vector role and human biting activity of Anophelinae mosquitoes in different landscapes in the Brazilian Amazon. Parasites Vectors 14, 236 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04725-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04725-2