Abstract

Background

Sichuan province is located in the southwest of China, and was previously a malaria-endemic region. Although no indigenous malaria case has been reported since 2011, the number of imported cases is on the rise. Insecticide-based vector control has played a central role in the prevention of malaria epidemics. However, the efficacy of this strategy is gravely challenged by the development of insecticide resistance. Regular monitoring of insecticide resistance is essential to inform evidence-based vector control. Unfortunately, almost no information is currently available on the status of insecticide resistance and associated mechanisms in Anopheles sinensis, the dominant malaria vector in Sichuan. In this study, efforts were invested in detecting the presence and frequency of insecticide resistance-associated mutations in three genes that encode target proteins of several classes of commonly used insecticides.

Methods

A total of 446 adults of An. sinensis, collected from 12 locations across Sichuan province of China, were inspected for resistance-conferring mutations in three genes that respectively encode acetylcholinesterase (AChE), voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC), and GABA receptor (RDL) by DNA Sanger sequencing.

Results

The G119S mutation in AChE was detected at high frequencies (0.40–0.73). The predominant ace-1 genotype was GGC/AGC (119GS) heterozygotes. Diverse variations at codon 1014 were found in VGSC, leading to three different amino acid substitutions (L1014F/C/S). The 1014F was the predominant resistance allele and was distributed in all 12 populations at varying frequencies from 0.03 to 0.86. The A296S mutation in RDL was frequently present in Sichuan, with 296SS accounting for more than 80% of individuals in six of the 12 populations. Notably, in samples collected from Chengdu (DJY) and Deyang (DYMZ), almost 30% of individuals were found to be resistant homozygotes for all three targets.

Conclusions

Resistance-related mutations in three target proteins of the four main classes of insecticides were prevalent in most populations. This survey reveals a worrisome situation of multiple resistance genotypes in Sichuan malaria vector. The data strengthen the need for regular monitoring of insecticide resistance and establishing a region-customized vector intervention strategy.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria represents one of the most severe vector-borne diseases, posing a significant threat to global public health [1]. In 2018, an estimated 228 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide, with most malaria cases found in the WHO African Region (93%), followed by the WHO South-East Asia Region (3.4% of the cases). There were an estimated 405,000 deaths from malaria globally, notably children under the age of 5 years, accounting for 67% of all malaria deaths worldwide [2].

Vector control has played an essential role in the prevention of epidemics caused by indigenous cases and secondary infections induced by imported cases [3]. The control of malaria vectors has relied primarily on the use of various classes of insecticides via either indoor residual spraying (IRS) or treatment of bed nets. Organochlorines, organophosphates, carbamates, and pyrethroids are four groups of insecticides recommended by WHO for indoor residual spraying [4]. These insecticides have been heavily used in agriculture. The intensive use of these insecticides in mosquito-targeted control and in agriculture has led to widespread insecticide resistance in malaria vector species [5].

Sichuan province is located in the southwest of China, with a population of more than 80 million. Except for the northwest region with high altitude and cold weather, the natural environment in most parts of Sichuan is suitable for breeding of malaria vectors [6]. In fact, Sichuan was historically a malaria-endemic region. Thanks to the implementation of the National Malaria Control Programme launched in China in 1955, the malaria morbidity rate in Sichuan decreased from 87.4 per 10,000 people (580,771 patients in total) in 1954 to 0.017 per 10,000 people in 2012, and no indigenous malaria case has been reported since 2011 [6]. However, the number of imported cases is on the rise [6]. For example, a total of 290 imported malaria cases were reported in Sichuan province in 2015 [7], indicating that the risk of malaria resurgence remains.

Anopheles sinensis has become the dominant malaria vector in most regions of China including Sichuan [8, 9]. Given that resistance will diminish the effectiveness of current insecticide-based malaria vector-control interventions, regular insecticide resistance monitoring is essential to inform evidence-based vector control. Unfortunately, currently available information about the status of insecticide resistance in Sichuan An. sinensis is sparse. In this study, efforts were invested to reveal the molecular resistance status by detecting the presence and frequency of resistance alleles of three genes encoding targets of commonly used insecticides (i.e. acetylcholinesterase encoded by the ace-1 gene, voltage-gated sodium channel encoded by the vgsc gene, and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor encoded by the rdl gene) in An. sinensis populations collected from 12 sites across Sichuan province of China.

Methods

Anopheles sinensis adults used in the study were caught around pigsties or cowsheds by light traps (wave length ~ 365 nm) between August and September 2018 from 12 locations across Sichuan province of China. In these regions, rice and vegetables are the main crops, and organophosphates (e.g. dichlorvos) and pyrethroids (e.g. cypermethrin, λ-cyhalothrin) are commonly used insecticides. Brief information about the 12 sample collection locations is listed in Table 1. Mosquitoes were trapped from 20:00 to 8:00 for 1 to 4 consecutive days at each location using 1–3 light traps, and were pooled for analysis. The specimens were morphologically identified and kept in 75 or 95% ethanol at 4 °C. Species identification was confirmed molecularly based on the nucleotide sequences of the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) region of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) as described previously [10].

The genomic DNA (gDNA) of individual mosquitoes, excluding the abdomen, was isolated according to a previously described protocol [11]. Briefly, individual samples were placed in a tube with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer containing 100 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA, with 1% (w/v) SDS, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.15 mM spermine, and 0.1 mg/ml (20 U/mg) proteinase K, and incubated at 60 °C for 20 min. After the addition of 75 µl of 8 M potassium acetate, the samples were mixed and set in an ice bath for 10 min and spun at 14,000×g for 5 min, after which the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Then, 1 ml of absolute ethanol was added and the samples were kept at room temperature for 10 min. The samples were spun at 14,000×g for 10 min. Pellets were washed in 0.5 ml of 70% ethanol and spun at 14,000×g for 5 min. The pellets were dried and then re-suspended in H2O. The concentration of gDNA was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. gDNA samples were stored at −20 °C until use. Gene fragments containing codon 119 of ace-1, codon 1014 of vgsc, and codon 296 of rdl were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Table 2. The PCR mixture (50 μl) consisted of 25 μl of 2× TIANGEN mix, 1 μl of each primer (5 μM), 1 μl of gDNA template, and ddH2O. The reactions were programmed as 95 °C for 2 min, 38 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55–62 °C for 30 s (Table 2), 72 °C for 50 s, and an extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

PCR products from individuals were visualized on agarose gels, and directly sequenced after purification using forward primers by TsingKe Company (Beijing, China). All sequencing data were checked manually. All confirmed DNA sequences were aligned by MUSCLE 3.8 [12], and nucleotide variations were documented. An independent chi-squared test was carried out to compare the overall difference in the allele frequency among An. sinensis populations by GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was estimated using Genepop on the Web v.4.7.5 (https://genepop.curtin.edu.au/).

Results

Distribution and frequency of ace-1 genotypes

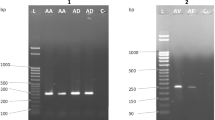

A variation (GGC to AGC) that causes an amino acid substitution (G to S) was observed at the first nucleotide of codon 119 of the ace-1 gene (Fig. 1). The G119S replacement in the AChE can confer resistance to organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate (CM) insecticides. All three possible genotypes (119GG, 119GS, 119SS) were detected (Fig. 1; Table 3). The predominant genotype was the 119GS heterozygote: over 50% of individuals were 119GS in 11 of the 12 tested populations. In contrast, the susceptible homozygotes (119GG) were relatively rare, with frequencies ranging from 0 to 0.31. Appreciable frequencies (0.08–0.46) of resistant homozygotes were detected (Table 3).

Distribution and frequency of kdr genotypes

Variations were detected at the second (T to G or C) and third nucleotide (G to T or C) of codon 1014 of the vgsc gene, leading to three amino acid substitutions at position 1014 (L to F/C/S) (Fig. 2). Ten different genotypes were identified in total, and 1014F was observed to be encoded by either TTC or TTT (Fig. 2). Based on the amino acid at position 1014, three to five different vgsc genotypes were distributed in a specific population (Table 4). Genotypes LL, FF, LF, and LC were widely distributed, while LS and CC were found only in PZH and LZJY, at very low frequency, respectively. LF and FF were the predominant genotypes in most locations.

Distribution and frequency of rdl genotypes

DNA sequencing identified a non-silent mutation at the first nucleotide of codon 296 of the rdl gene, leading to a deduced amino acid substitution of A (GCA) to S (TCA) (Fig. 3). Three different genotypes (296SS, 296AS, and 296AA) were detected in our specimens (Table 5). With the exception of PZH, the frequency of mutant homozygotes was high, with 296SS accounting for more than 80% of individuals in six of the 12 populations. Notably, the wild 296AA homozygote was not detectable in eight of the 12 populations, while 100% of individuals were resistant 296SS homozygotes in DJY and DYMZ.

Distribution and frequency of triple-target genotype combinations

From the 446 individuals, 34 triple-target genotype combinations were documented (Table 6). Among these, C18 (119GS + 1014LF + 296SS) and C23 (119GS + 1014FF + 296SS) were the most widely distributed combinations. Moreover, the three-target resistance homozygous genotype (C33) was also widely distributed. Most notably, almost 30% of individuals were found to be resistant homozygotes (C33 and C34) for all three targets in DJY and DYMZ.

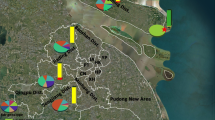

Distribution and frequency of resistance alleles

The frequency of resistance alleles is summarized in Fig. 4. AChE1-119S was found at a frequency ranging between 0.40 and 0.73 (Table 3). VGSC-1014F was the predominant resistance allele in each location, and was distributed in all 12 populations, with frequency varying from 0.03 to 0.86. VGSC-1014C was present in ten populations, with frequency of 0.02–0.15, while VGSC-1014S was observed only in PZH, with a frequency of 0.013 (Table 4). High frequencies of RDL-296S (0.69–1.00) were detected in 11 locations, the exception being PZH (Table 5). Chi-square tests indicated that the insecticide resistance-related mutations were heterogeneously distributed in the 12 populations (Tables 3, 4, 5).

Discussion

The control of disease-borne insects has heavily relied on the use of insecticides. The evolution of insecticide resistance worldwide has been well recognized as a major obstacle in effective vector control [1]. Implementation of vector-control interventions should take into account the resistance situation of local disease vectors. However, there have been almost no published data to inform the status and underlying genetic mechanisms of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector An. sinensis in Sichuan. The current work represents the first extensive survey of target-site mutations in An. sinensis populations across Sichuan.

Acetylcholinesterase is the primary molecular target of organophosphates (OP) and carbamates (CM). The G119S replacement in AChE is associated with OP and CM resistance in several important mosquito species [13,14,15,16,17]. In Sichuan, this conservative mutation was detected in all An. sinensis populations (Table 2 and Fig. 4). This result is in keeping with observations in published literature indicating that the G119S mutation is widely distributed in An. sinensis in Asia [10, 18,19,20,21]. The high frequency (0.40–0.73, with an average of 0.56) of the resistant 119S allele strongly indicates the occurrence of appreciable resistance to OP and CM in these regions.

VGSC is the major target for pyrethroids and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) [21]. Many studies have demonstrated that mutations at codon 1014 of the vgsc gene are able to confer resistance to both pyrethroids and DDT in many arthropod species including anophelines [22, 23]. In An. sinensis, significant positive correlations have been found between kdr allele frequency and bioassay-based resistance phenotype, and three different mutations of VGSC at position 1014 (1014F/C/S) have been documented [20, 21, 24,25,26,27,28]. We found that all three mutations were present in Sichuan. In contrast to the situation with An. sinensis in Guangxi, China, where relatively higher frequencies of 1014C or 1014S than 1014F were observed [21, 27], 1014F is the predominant resistance allele in Sichuan (Table 4; Fig. 4).

The insect gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor RDL subunit encoded by the rdl (resistance to dieldrin) gene plays a central role in neuronal signaling and is involved in various processes [29]. RDL has been the primary target for insecticides of various chemical structures including cyclodienes and fipronil [29], and a potential secondary target for neonicotinoids and pyrethroids [30]. In this study, the A296S mutation was identified and found to be widely distributed in An. sinensis populations across Sichuan (Table 5; Fig. 4). These data would predict a risk of resistance to the old cyclodienes and relatively new phenylpyrazoles in Sichuan populations of An. sinensis.

For vgsc 1014 and rdl 327 loci, genotype frequencies were detected in conformity to HWE (Tables 4 and 5). However, there was a significant departure from the HWE at the ace-1 119 locus in six of the 12 populations (Table 3). Significant heterozygote excess may suggest that there is a heterologous duplication in ace-1 in these populations, although the possibility of selection for heterozygotes in the field cannot be excluded. Duplication of the ace-1 gene has been reported in several mosquito species including Anopheles and Culex [31,32,33,34], but not in An. sinensis, to the best of our knowledge. Previous studies have demonstrated that permanent ace-1 heterozygotes exhibit resistance to both OP and CM, and a reduction of fitness costs [32, 33], whether heterologous duplication is present in An. sinensis ace-1 deserves further investigation.

Taken together, the results show that several well-known genetic mutations associated with insecticide resistance in An. sinensis are widely distributed with high frequency in Sichuan. This situation may be explained in part by the application of a large amount of insecticides immediately after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and/or insecticide-based vector-control campaigns for building “healthy cities” in recent decades. Moreover, this survey reveals the presence of individuals harboring mutations in more than one insecticidal target (Table 6). Even worse, in DJY and DYMZ, about 30% of individuals were resistant homozygotes for all three targets (Table 6).

Conclusions

In this survey, we found the occurrence of resistance-related mutations in multiple targets of the four main classes of insecticides. Notably, these target site mutations were present at high frequencies in most An. sinensis populations. Geographical heterogeneities of allele frequency among different locations were significant. These findings emphasize the need to establish a location-customized resistance management strategy before implementing insecticide-based malaria control programmes.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets are presented in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AChE:

-

Acetylcholinesterase

- CM:

-

Carbamate insecticides

- GABA:

-

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- kdr :

-

Knockdown resistance

- OC:

-

Organochlorine insecticides

- OP:

-

Organophosphorus insecticides

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PY:

-

Pyrethroid insecticides

- VGSC:

-

Voltage-gated sodium channel

- RDL:

-

Resistance to dieldrin

References

Enayati A, Hemingway J. Malaria management: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:569–91.

WHO. World Malaria Report. Geneva. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019. p. 2019.

Zhang S, Guo S, Feng X, Afelt A, Frutos R, Zhou S, et al. Anopheles vectors in mainland China while approaching malaria elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:889–911.

WHO. Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

WHO. World Malaria Report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2017

Xu GJ, Li L, Yu T, Wu XH. Epidemic situation and progress in eliminating malaria in Sichuan. J Prev Med Inf. 2014;30:783–5.

Li L, Liu Y, Xu GJ, Yu T, Zou Y, Wu XH, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of imported malaria in Sichuan Province in 2015. Chin J Parasitol Para Dis. 2017;35:75–85.

Wu H, Lu L, Meng F, Guo Y, Liu Q. Reports on national surveillance of mosquitoes in China, 2006–2015. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2017;28:409–15.

Guo Y, Wu H, Liu X, Yue Y, Ren D, et al. National vectors surveillance report on mosquitoes in China, 2018. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2019;30:128–33.

Feng X, Yang C, Yang Y, Li J, Lin K, Li M, et al. Distribution and frequency of G119S mutation in ace-1 gene within Anopheles sinensis populations from Guangxi. China Malar J. 2015;14:470–4.

Rinkevich FD, Hedtke SM, Leichter CA, Harris SA, Su C, Brady SG, et al. Multiple origins of kdr-type resistance in the house fly Musca domestica. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52761.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7.

Weill M, Lutfalla G, Mogensen K, Chandre F, Berthomieu A, Berticat C, et al. Insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors. Nature. 2003;423:136–7.

Weill M, Malcolm C, Chandre F, Mogensen K, Berthomieu A, Marquine M, et al. The unique mutation in ace-1 giving high insecticide resistance is easily detectable in mosquito vectors. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13:1–7.

Fournier D. Mutations of acetylcholinesterase which confer insecticide resistance in insect populations. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157:257–65.

Essandoh J, Yawson AE, Weetman D. Acetylcholinesterase (Ace-1) target site mutation 119S is strongly diagnostic of carbamate and organophosphate resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles coluzzii across southern Ghana. Malar J. 2013;12:404.

Misra BR, Gore M. Malathion resistance status and mutations in acetylcholinesterase gene (Ace) in Japanese encephalitis and flariasis vectors from endemic area in India. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:442–6.

Baek JH, Kim HW, Lee WJ, Lee SH. Frequency detection of organophosphate resistance allele in Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae) populations by real-time PCR amplification of specific allele (rtPASA). J Asia-Pac Entomol. 2006;9:375–6.

Chang XL, Zhong DB, Fang Q, Hartsel J, Zhou GF, Shi LN, et al. Multiple resistances and complex mechanisms of Anopheles sinensis mosquito: a major obstacle to mosquito-borne diseases control and elimination in China. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2889.

Qin Q, Li YJ, Zhong DB, Zhou N, Chang XL, Li CY, et al. Insecticide resistance of Anopheles sinensis and An. vagus in Hainan Island, a malaria endemic area of China. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:92.

Yang C, Feng X, Liu N, Li M, Qiu X (2019) Target-site mutations (AChE-G119S and kdr) in Guangxi Anopheles sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border. Parasit Vectors 12(1):77

Dong K, Du YZ, Rinkevich F, Nomura Y, Xu P, Wang LX, et al. Molecular biology of insect sodium channels and pyrethroid resistance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;50:1–17.

Silva APB, Santos JMM, Martins AJ. Mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of anophelines and their association with resistance to pyrethroids—a review. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:450.

Zhong D, Chang X, Zhou G, He Z, Fu F, Yan Z, et al. Relationship between knockdown resistance, metabolic detoxification and organismal resistance to pyrethroids in Anopheles sinensis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55475.

Tan WL, Li CX, Wang ZM, Liu MD, Dong YD, Feng XY, et al. First Detection of multiple knockdown resistance (kdr) like mutations in voltage-gated sodium channel using three new genotyping methods in Anopheles sinensis from Guangxi Province. China J Med Entomol. 2012;49:1012–9.

Wang Y, Yu W, Shi H, Yang Z, Xu J, Ma Y. Historical survey of the kdr mutations in the populations of Anopheles sinensis in China in 1996–2014. Malar J. 2015;14:120–9.

Yang C, Feng X, Huang Z, Li M, Qiu X. Diversity and frequency of kdr mutations within Anopheles sinensis populations from Guangxi. China Malar J. 2016;15:411–8.

Fang Y, Shi W, Wu J, Li Y, Xue J, Zhang Y. Resistance to pyrethroid and organophosphate insecticides, and the geographical distribution and polymorphisms of target-site mutations in voltage-gated sodium channel and acetylcholinesterase 1 genes in Anopheles sinensis populations in Shanghai. China Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:396.

Taylor-Wells J, Brooke BD, Bermudez I, Jones AK. The neonicotinoid imidacloprid, and the pyrethroid deltamethrin, are antagonists of the insect Rdl GABA receptor. J Neurochem. 2015;135:705–9.

Casida JE, Durkin KA. Novel GABA receptor pesticide targets. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2015;121:22–10.

Weetman D, Djogbenou LS, Lucas E. Copy number variation (CNV) and insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: evolving knowledge or an evolving problem? Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018;27:82–8.

Labbe P, Berthomieu A, Berticat C, Alout H, Raymond M, Lenormand T, Weill M. Independent duplications of the acetylcholinesterase gene conferring insecticide resistance in the mosquito Culex pipiens. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1056–67.

Assogba BS, Milesi P, Djogbenou LS, Berthomieu A, Makoundou P, Baba-Moussa LS, Fiston-Lavier AS, Belkhir K, Labbe P, Weill M. The ace-1 locus is amplified in all resistant Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes: fitness consequences of homogeneous and heterogeneous duplications. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e2000618.

Weetman D, Mitchell SN, Wilding CS, Birks DP, Yawson AE, Essandoh J, Mawejje HD, Djogbenou LS, Steen K, Rippon EJ, et al. Contemporary evolution of resistance at the major insecticide target site gene Ace-1 by mutation and copy number variation in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:2656–72.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Xiuye Yang, Jipu Zou, Jing Feng, Jinsong Li, Chunxue Le, Yanjun Zeng, Xiqiang Zeng, Tingting Sang, and Xiping Luo for assistance in mosquito collection. We are grateful to the reviewers for their helpful comments, and to Mr. Ruoyao Ni for help in statistical analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Project of China on Infectious Diseases (No. 2017ZX10303404) and the State Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Pest Insects and Rodents (IPM1915). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WPQ and XHQ conceived the study. NL performed the molecular experiments. NL and XHQ analyzed the data. XHQ, LN, and WPQ wrote the paper. YY, JL, JH, ZC, and ML contributed to sample collection, species classification, and draft discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Qian, W., Liu, N., Yang, Y. et al. A survey of insecticide resistance-conferring mutations in multiple targets in Anopheles sinensis populations across Sichuan, China. Parasites Vectors 14, 169 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04662-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04662-0