Abstract

Background

Countries of eastern Europe are considered, due to several risk factors, more vulnerable to infections with newly (re)emerging pathogens. During the last decade, in several European countries, reports of autochthonous cases of ocular thelaziosis due to Thelazia callipaeda have been published, posing a great concern from both veterinary and public health perspective. However, in the Republic of Moldova only limited epidemiological data are available regarding zoonotic vector-borne pathogens and, until now, no data exist on the zoonotic nematode T. callipaeda.

Methods

In September 2018, an 11-year-old dog, mixed-breed, intact male was referred to a private veterinary clinic from Chișinău, Republic of Moldova, with a history of 2 weeks of an ocular condition affecting the right eye. The ophthalmological exam revealed the presence of nematode parasites in the conjunctival sac and under the third eyelid. The collected parasites were identified by morphological techniques and molecular analysis.

Results

A total of 7 nematodes were collected, and 5 females and 2 males of T. callipaeda were identified morphologically. The BLAST analysis confirmed the low genetic variability of this parasite in Europe. The travel history of the patient allowed us to confirm the autochthonous character of the case.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of thelaziosis in dogs from the Republic of Moldova, which confirms the spreading trend of T. callipaeda and the existence of an autochthonous transmission cycle of this zoonotic parasite in the country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Canine vector-borne diseases (CVBDs) of zoonotic concern consist in a group of illnesses affecting both human and canine populations. They are caused by aetiological agents of variable pathogenicity and are transmitted by arthropod vectors. CVBDs rapid spreading worldwide in areas considered previously as non-endemic or with sporadic cases, the important role of dogs in the modern society involving a close and long-lasting contact with humans, and the favourable environmental conditions for development of vectors have led to an increasing veterinary and public health interest in these diseases [1]. Different favouring factors such as climate change, urbanization, land use, etc., have increased the exposure risk for both dogs and humans in many areas worldwide [1].

However, despite the high general interest and number of studies conducted to assess CVBD’s epidemiology, the mechanisms involved in these diseases transmission and clinical expression, and the complex role of asymptomatic dogs are not completely understood [1, 2]. This is mainly due to insufficient data on vectors and pathogens distribution, and the lack of recent and updated surveillance studies [1]. Among CVBDs, ocular thelaziosis is regarded as having a moderate zoonotic relevance [1]. In Europe and Asia, the sole aetiological agent, Thelazia callipaeda, is a parasite localised in the conjunctival sacs, naso-lacrimal ducts, under the eyelids and the nictitating membrane in different species of mammals, predominantly in domestic and wild carnivores, and also in humans [3, 4]. This nematode is responsible for ocular symptoms of variable severity: epiphora, local pruritus and congestion, photophobia, mild to severe conjunctivitis and keratitis, which can evolve to cornea opacification and even ulceration in the absence of diagnosis and therapy [4, 5].

Although until 2005 the complete life-cycle of this parasite was not known, nowadays, the biology is elucidated in both the intermediate and definitive hosts [5,6,7]. Thelazia callipaeda is transmitted by male Phortica variegata (Drosophilidae) that feed on the definitive hosts’ lachrymal secretions. In the lachrymal secretions of parasitized mammals, first-stage larvae (L1) are released by adult females after mating. During the feeding process, the flies become infected with L1, which undergo a series of transformations and become infective L3 stage in the body of the intermediate host. L3 larvae are inoculated to the receptive host during the feeding process, and consecutively develop to adults [4, 7]. The parasite was known for decades as the “oriental eye worm” due to its distribution limited to different territories of Asia and the former Soviet Union [3]. In Europe, T. callipaeda was first reported in dogs in Italy [8]. Regarded initially as a “new” agent of an ocular condition in various species of domestic and wild mammals, and also in humans, it is now considered endemic in many regions of different European countries such as Spain, Portugal, Italy, France and Switzerland [9,10,11,12,13]. However, in the last decade, in many other countries (Croatia, Romania, Hungary, Bosnia and Herzegovina) previously considered outside of the distribution area, autochthonous cases of ocular thelaziosis caused by T. callipaeda in dogs were reported, highlighting an eastern spreading of this parasite [14]. Moreover, in the same time frame, reports in other host species (e.g. cats, wild cats, mustelids, golden jackals, foxes, lagomorphs) have been published [12, 15]. It is now clear that there is a positive relation between animal and human cases. In areas where the disease is highly prevalent in pets (cats and dogs) and wild carnivores (especially in foxes, that seem to play an important role in the epidemiology of T. callipaeda), human cases may occur [5, 14]. In different countries of eastern Europe, the socio-economic instability of the last three decades, the low awareness of veterinarians and physicians on newly (re)emerging pathogens and the high density of rural, poor communities, are considered as important risk factors for neglected diseases. Infection with T. callipaeda is considered as one of these diseases [14]. Moreover, there is a lack in scientific data regarding vector-borne pathogens’ epidemiology in these geographical areas.

This study presents the first autochthonous case of ocular thelaziosis in a dog in the Republic of Moldova and identifies the haplotype circulating in this country, thus extending the knowledge on the epidemiology of T. callipaeda in Europe.

Methods

In September 2018, an 11-year-old dog, mixed-breed, intact male, with a history of ocular condition affecting the right eye for a period of 2 weeks was referred to a private veterinary clinic from Chișinău, the capital city located in the centre of the Republic of Moldova. The dog was born and had lived its entire life in a private yard from a neighbourhood located in north-western Chișinău (47°02′03″N, 28°47′17″E).

A general and an ophthalmological consultation were performed. Physical examination revealed a good condition of the animal. Due to the excessive ocular discharge and blepharospasms, the ophthalmic examination of the right eye was possible only after the administration of a local anaesthetic. The close examination of this eye revealed the presence of translucent and mobile parasites in the conjunctival sac and under the third eyelid. All worms were mechanically removed from the affected eye, by using sterile, blunt tweezers and by flushing of the conjunctival sac with saline solution (0.9% NaCl). The dog was treated by application of a single dose spot-on formulation containing imidacloprid 10% and moxidectin 2.5%. The collected parasites were preserved in tubes with formalin or absolute ethanol for further investigations. The owner provided the travel history of the dog and verbally consented to the usage of the collected material for scientific purpose.

To perform the morphological identification, the specimens stored in formalin were mounted on a glass slide. Microscopic examination was performed using an Olympus BX61 with an adapted DP72 camera. Morphological keys and descriptions available in the literature were used for the parasite identification [16]. The genomic DNA was extracted from specimens (2 females) preserved in absolute ethanol, by using a commercial kit (Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit, Bioline, London, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA samples were further processed by PCR amplification of a 670-bp fragment of the cox1 gene using the NTF/NTR primer pair, as previously described [17]. The amplicons were sequenced using an external service (performed at Macrogen Europe, Amsterdam, NL) and the attained sequences were compared to those available in the GenBank database by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis.

Results

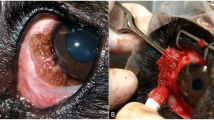

Following the ophthalmological examination, seven nematodes were collected from the right eye; close examination of the eye revealed conjunctivitis, epiphora, periocular alopecia and erosions. The left eye presented no lesions and no parasites were detected. According to the owner, the dog never travelled abroad. All collected nematodes were examined by light microscopy. All parasites presented specific features, which allowed sex and species identification based on published morphological identification keys [16]. Five females and two males of T. callipaeda were identified. The anterior extremity of the recovered worms presented a serrated cuticle with transverse striations (Fig. 1a). The sex was assigned based on several characteristics; T. callipaeda males were characterised by a curved posterior extremity, with pre- and post-cloacal papillae and two unequal spicules (Fig. 1b); females of T. callipaeda presented the vulvar opening situated anterior to the oesophago-intestinal junction, and the proximal end of the uterus contained L1 larvae (Fig. 1c).

a Anterior extremity of recovered worms: a serrated cuticle with transverse striations and a buccal capsule; b Male, posterior extremity with pre- and post-cloacal papillae and two unequal spicules; c Gravid female, with the vulvar opening situated anterior to the esophago-intestinal junction, and the proximal end of the uterus containing L1 larvae

The BLAST analysis of the two sequences revealed a 100% nucleotide similarity to a sequence of T. callipaeda haplotype h1 (GenBank: AM042549) in both cases. The sequence was deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number MN163032.

Discussion

The present study represents the first report of canine ocular thelaziosis caused by T. callipaeda in the Republic of Moldova. Reported initially as sporadic, this disease has rapidly become endemic in different countries of the Mediterranean Basin (i.e. Spain, Portugal, Italy and France) and western Europe (Switzerland). Recently, many other countries from eastern Europe (Croatia, Romania, Hungary and Bosnia and Herzegovina) reported “first autochthonous cases” of canine thelaziosis, confirming the north-eastern spreading of this parasites. So far, the eastern limit of the distribution area of T. callipaeda in Europe was defined by various reports from Greece [18], Bulgaria, Romania [14, 19] and Slovakia [20]. Considering the latest expanding trend and the recent reports from the bordering countries (Romania and Slovakia), the following cases should have been expected from Ukraine and/or Republic of Moldova, where, to the best of our knowledge, the parasite has not been reported yet.

In this frame, the present report confirms the expected spread of this nematode and establishes a new eastern distribution limit in Europe. This finding is of particular importance due to its autochthonous character. Given that the dog had never travelled outside the country and the Republic of Moldova is considered as a suitable location for the development of P. variegata [21], the proven vector of this parasite [6, 7], is an important proof that sustain the existence of an autochthonous transmission cycle of the zoonotic parasite T. callipaeda in the Republic of Moldova. Dogs serve as sentinels for human infection in case of different CVBDs [22], including ocular thelaziosis [5]. The close relationship between the parasites’ biology in dogs, other animal hosts (both wild and domestic) and humans is sustained by the occurrence of human cases in areas where the infection in animals is established and also by the low genetic variability of T. callipaeda in Europe [5]. Although in Asia other 21 haplotypes have been identified [23], so far only the haplotype h1 has been identified in Europe, regardless the host species [23, 24].

The BLAST analysis of our sequences revealed a 100% similarity to a sequence of T. callipaeda haplotype h1, extending the knowledge on this nematode to other territories, where no data were available. This finding also strengthens the hypothesis that in Europe, the spread of the parasite was generated by a single introduction event followed by numerous transmissions [24]. The relatively rapid dissemination of T. callipaeda was facilitated by its high adaptability for survival [24] and by circulation of companion animals, especially dogs, between the European countries [21]. For instance, it is suspected that canine T. callipaeda was initially introduced in Spain through hunting dogs from Italy and/or travelling companion animals from France, both countries being endemic at that time [25]. Moreover, the first case of thelaziosis in the UK was reported in a dog imported from Romania (neighbouring country of the Republic of Moldova). The same study presented two other cases in patients (dogs) with recent history of travel in endemic countries (Italy and France) [26]. All pets, mainly dogs originating in areas were the disease has been reported, may act as sources of T. callipaeda, and by travels or importations can pose a risk for canine and human population in their non-endemic destinations [26].

In most countries (i.e. Italy, France, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia) where T. callipaeda is now present, the history of ocular thelaziosis started with case reports in dogs, that were shortly followed by other reports in various species and/or by epidemiological survey that highlighted a more extensive character of the disease. In the absence of any scientific data regarding thelaziosis in the Republic of Moldova, we can only presume that this report is the first of those to come. Our finding highlights the need for additional large-scale studies that should provide information on the current situation of thelaziosis in this country. In many countries where the disease has been reported, it is believed that the information related to this parasite gained in the veterinary field are more consistent and refined compared with those available in human medicine [5], stressing out the importance of the One Health approach. It is now clear that only by providing updated epidemiological data that can increase the awareness of both veterinarians and physicians, the prevention and the early diagnosis of the diseases are possible.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of autochthons thelaziosis in dogs from the Republic of Moldova. This study extends the current geographical distribution of T. callipaeda, confirms the low genetic variability of the nematode in Europe and highlights the importance of thelaziosis in the differential diagnosis of ocular conditions in both animals and humans from the Republic of Moldova.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CVBD:

-

canine vector-borne disease

- BLAST:

-

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

References

Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Breitschwerdt EB. Managing canine vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern: part one. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:157–63.

Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Breitschwerdt EB. Managing canine vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern: part two. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:228–35.

Anderson RC. Nematode parasites of vertebrates. Their development and transmission. 2nd ed. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 2000.

Otranto D, Traversa D. Thelazia eyeworm: an original endo-and ecto-parasitic nematode. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:1–4.

Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F. Transmission of the eyeworm Thelazia callipaeda: between fantasy and reality. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:273.

Otranto D, Lia RP, Cantacessi C, Testini G, Troccoli A, Shen JL, Wang ZX. Nematode biology and larval development of Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in the drosophilid intermediate host in Europe and China. Parasitology. 2005;131:847–55.

Otranto D, Cantacessi C, Testini G, Lia RP. Phortica variegata as an intermediate host of Thelazia callipaeda under natural conditions: evidence for pathogen transmission by a male arthropod vector. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1167–73.

Rossi L, Bertaglia PP. Presence of Thelazia callipaeda Railliet & Henry, 1910 in Piedmont, Italy. Parassitologia. 1989;31:167–72.

Marino V, Gálvez R, Colella V, Sarquis J, Checa R, Montoya A, et al. Detection of Thelazia callipaeda in Phortica variegata and spread of canine thelaziosis to new areas in Spain. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:195.

Maia C, Catarino AL, Almeida B, Ramos C, Campino L, Cardoso L. Emergence of Thelazia callipaeda infection in dogs and cats from East-Central Portugal. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016;63:416–21.

Otranto D, Ferroglio E, Lia RP, Traversa D, Rossi L. Current status and epidemiological observation of Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in dogs, cats and foxes in Italy: a “coincidence” or a parasitic disease of the Old Continent? Vet Parasitol. 2003;116:315–25.

Dorchies P, Chaudieu G, Siméon LA, Cazalot G, Cantacessi C, Otranto D. First reports of autochthonous eyeworm infection by Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in dogs and cat from France. Vet Parasitol. 2007;149:294–7.

Malacrida F, Hegglin D, Bacciarini L, Otranto D, Nägeli F, Nägeli C, et al. Emergence of canine ocular thelaziosis caused by Thelazia callipaeda in southern Switzerland. Vet Parasitol. 2008;157:321–7.

Colella V, Kirkova Z, Fok É, Mihalca AD, Tasić-Otašević S, Hodžić A, et al. Increase in eyeworm infections in eastern Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1513.

Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Mallia E, DiGeronimo PM, Brianti E, Testini G, et al. Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida, Thelaziidae) in wild animals: report of new host species and ecological implications. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166:262–7.

Otranto D, Lia RP, Traversa D, Giannetto S. Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida: Thelaziidae) of carnivores and humans: morphological study by light and scanning electron microscopy. Parassitologia. 2003;45:125–33.

Casiraghi M, Anderson TJC, Bandi C, Bazzocchi C, Genchi C. A phylogenetic analysis of filarial nematodes: comparison with the phylogeny of Wolbachia endosymbionts. Parasitology. 2001;122:93–103.

Diakou A, Di Cesare A, Tzimoulia S, Tzimoulias I, Traversa D. Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida: Thelaziidae): first report in Greece and a case of canine infection. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:2771–5.

Mihalca AD, D’Amico G, Scurtu I, Chirilă R, Matei IA, Ionică AM. Further spreading of canine oriental eyeworm in Europe: first report of Thelazia callipaeda in Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:48.

Čabanová V, Kocák P, Víchová B, Miterpáková M. First autochthonous cases of canine thelaziosis in Slovakia: a new affected area in central Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:179.

Palfreyman J, Graham-Brown J, Caminade C, Gilmore P, Otranto D, Williams DJ. Predicting the distribution of Phortica variegata and potential for Thelazia callipaeda transmission in Europe and the United Kingdom. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:272.

Day MJ. The immunopathology of canine vector-borne diseases. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:48.

Zhang X, Shi YL, Han LL, Xiong C, Yi SQ, Jiang P, et al. Population structure analysis of the neglected parasite Thelazia callipaeda revealed high genetic diversity in Eastern Asia isolates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006165.

Otranto D, Testini G, De Luca F, Hu M, Shamsi S, Gasser RB. Analysis of genetic variability within Thelazia callipaeda (Nematoda: Thelazioidea) from Europe and Asia by sequencing and mutation scanning of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene. Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19:306–13.

Miró G, Montoya A, Hernández L, Dado D, Vázquez MV, Benito M, et al. Thelazia callipaeda: infection in dogs: a new parasite for Spain. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:148.

Graham-Brown J, Gilmore P, Colella V, Moss L, Dixon C, Andrews M, et al. Three cases of imported eyeworm infection in dogs: a new threat for the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 2017;181:346.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work of MOD and GD, was supported by CNCS-UEFISCDI Grant Agency Romania, Grant Numbers PD38/2018 and PD35/2018 respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MOD wrote and designed the manuscript. GD and AMI performed morphological and molecular identification of the parasites. NC performed the clinical examination of the dog and collected the parasites. GD and EV were contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dumitrache, M.O., Ionică, A.M., Voinițchi, E. et al. First report of canine ocular thelaziosis in the Republic of Moldova. Parasites Vectors 12, 505 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3758-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3758-3