Abstract

Background

Aedes aegypti is the principal vector of several important arboviruses. Among the methods of vector control to limit transmission of disease are genetic strategies that involve the release of sterile or genetically modified non-biting males, which has generated interest in manipulating mosquito sex ratios. Sex determination in Ae. aegypti is controlled by a non-recombining Y chromosome-like region called the M locus, yet characterisation of this locus has been thwarted by the repetitive nature of the genome. In 2015, an M locus gene named Nix was identified that displays the qualities of a sex determination switch.

Results

With the use of a whole-genome bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library, we amplified and sequenced a ~200 kb region containing the male-determining gene Nix. In this study, we show that Nix is comprised of two exons separated by a 99 kb intron primarily composed of repetitive DNA, especially transposable elements.

Conclusions

Nix, an unusually large and highly repetitive gene, exhibits features in common with Y chromosome genes in other organisms. We speculate that the lack of recombination at the M locus has allowed the expansion of repeats in a manner characteristic of a sex-limited chromosome, in accordance with proposed models of sex chromosome evolution in insects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

At least 2.5 billion people live in areas where they are at risk of dengue transmission from mosquitoes, principally Ae. aegypti, with an estimated 390 million infections per year [1, 2]. Recently, the emergence of chikungunya and Zika viruses further highlights the public health importance of Ae. aegypti [3, 4]. Future mosquito control strategies may incorporate genetic techniques such as the sustained release of sterile or transgenic “self-limiting” mosquitoes [5, 6]. Given that only female mosquitoes bite and spread disease, there has been substantial interest in manipulating mosquito sex determination using these genetic techniques and others, including gene drive [7, 8]. Therefore, elucidating the genetic basis for sex determination could, for instance, facilitate production of male-only cohorts for release, or allow transformation of mosquitoes with sex-specific “self-limiting” gene cassettes.

Sex determination in insects is variable, and generally not well understood outside of model species [9]. Unlike the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae and Drosophila species, Ae. aegypti does not have heteromorphic (XY) sex chromosomes [10]. Instead, the male phenotype is determined by a non-recombining M locus on one copy of autosome 1 [11,12,13]. This locus is poorly characterised because its highly repetitive nature has confounded attempts to study it based on the existing genome assembly [14]. The initial 1376 Mb Ae. aegypti reference genome was assembled from Sanger sequencing reads in 2007 [15], which are commonly not long enough to span the repetitive transposable elements that comprise a large proportion of the genome [16], and consequently the assembly was relatively low quality [17]. Furthermore, the fact that both male and female genomic DNA was used for genome sequencing reduced the expected coverage of the M locus to one quarter of the autosome 1 sequences, further obscuring candidate M locus sequences [18].

Recently, a team of researchers was nevertheless able to identify Nix, a gene with male-specific, early embryonic expression. Knockout of Nix using CRISPR/Cas9 results in morphological feminisation of male mosquitoes along with feminisation of gene expression and female splice forms of the conserved sex-regulating genes doublesex (dsx) and fruitless (fru), strongly indicating that Nix is the upstream regulator of sexual differentiation [14]. The translated Nix protein contains two RNA recognition motifs and is hypothesised to be a splicing factor, acting either directly on dsx and fru or on currently unknown intermediates [19]. A comparison of sexually dimorphic gene expression in different mosquito tissue types also detected male-specific transcripts of Nix [20]. An ortholog of Nix is present in Ae. albopictus, but it is not known if the two are functionally homologous [21].

To date, Nix has only been characterised as an mRNA transcript. To fully understand this gene’s role in sex determination and to utilise this knowledge for vector control, it is essential to decipher its genomic context. For this purpose, this study identifies and describes the region of the M locus in which Nix is located.

Results

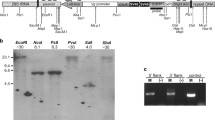

Four BAC clones positive for Nix assembled into a single region of 207 kb with no gaps and a GC content of 40.2% (submitted to the NCBI as accession KY849907). The presence of the Nix gene in the assembled BACs was confirmed by BLASTN. The whole gene was present in tiled BACs, though not completely within individual BAC clones. Neither Nix nor the complete region could be found in the AaegL3 or Aag2 reference genome assemblies. The newly released AaegL5 male assembly contains Nix [22], and the assembled BACs aligned to the corresponding region in AaegL5 with > 99.9% identity, spanning a 2899 bp gap in the AaegL5 genome that is comprised mainly of repeats (Additional file 1: Figures S1, S2). While Nix was originally identified in the genome-sequenced Liverpool strain [14], PCR revealed that it is exclusively present in male genomic DNA from other geographically varied Ae. aegypti populations (Additional file 1: Figure S3), further strengthening the evidence that it is wholly present in the M locus.

The Nix gene was found to be made up of two exons with a single intron of 99 kb (Fig. 1). Although large introns are not uncommon in Ae. aegypti (average intron length ~5000 bp) [15], this intron is at the extreme end of intron sizes observed (Additional file 1: Figure S4), especially considering the small size of its protein coding regions (< 1000 bp). The gene structure is confirmed by Illumina RNA-Seq data clearly showing reads spanning the intron between the two exons (Fig. 1). RepeatMasker identified approximately 55% of the sequenced region as repetitive, and the intron region of Nix as 72% repetitive (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Structure and gene expression of the ~207 kb genomic region containing the Nix gene. Nix is shown as two black boxes representing the exons, joined by a black line representing the intron. The top track of a shows the alignment of the sequence to the corresponding region of the reverse complement of the AaegL5 reference genome assembly, with colours representing percentage similarity (red: 100%; orange: > 90%; green: > 80%). Colours on the central track of a represent the classes of repetitive elements (orange: DNA transposons; cyan: Gypsy LTRs; green: Ty1/Copia LTRs). Blue histograms represent the coverage of RNA-Seq reads from male samples on the y axis; red histograms represent the coverage from female samples. b and c show enlargements of the first and second exons of Nix in the dotted regions in a, respectively

Discussion

The genomic data from our assembled M locus region show that Nix is approximately 100 kb in length - exceptionally long even for an insect, and one of the longest in the mosquito genome. This is particularly unusual because Nix is expressed in early embryonic development, before the onset of the syncytial blastoderm stage 3–4 hours after oviposition [14], during which time most active genes have very short introns, or lack them entirely. There is evidence of selection against intron presence in genes expressed in the early Ae. aegypti zygote [23]. In Drosophila, the majority of early-expressed genes have small introns and encode small proteins, suggesting that selection has favoured high transcript turnover during early embryonic development due to the requirement for short cell cycles and rapid division [24]. It might therefore be expected that selection would limit the Nix intron’s expansion to preserve efficient transcription in the zygote.

One possible explanation is the expansion of repetitive DNA. The RepeatMasker results reveal that the Nix region contains a high number of repetitive sequences, especially retrotransposons (Fig. 1, Additional file 2: Table S1). The M locus has accumulated repeats in between protein-coding DNA in a manner characteristic of a sex chromosome, which are prone to degeneration by Muller’s ratchet due to the lack of recombination [25,26,27]. For instance, repetitive sequences comprise almost the entire Anopheles gambiae Y chromosome, and these repetitive sequences show rapid evolutionary divergence [28]. Similarly, certain Y chromosome genes of the plant Silene latifolia have much larger introns than their X chromosome copies due to the insertion of retrotransposons [29]. A more extreme version of this phenomenon is seen in Drosophila, where some Y chromosome genes, such as those involved in spermatogenesis, have gigantic repetitive introns, sometimes in the megabase range, that consequently make them many times larger than typical autosomal genes [30, 31].

It is therefore possible that the lack of recombination may pose constraints on the structure of the M locus, and in the absence of strong selection the Nix gene has degenerated outside the coding regions. Non-recombining sex loci such as the Ae. aegypti M locus may represent an evolutionary precursor to differentiated sex chromosomes, which are thought to emerge when sexually antagonistic alleles accumulate on either chromosome and favour reduced recombination between the two homologs, eventually leading to degeneration and loss of genes on the proto-Y [32]. Recent data appears to show that recombination is reduced along chromosome 1 even outside of the M locus [33], while the fully differentiated Anopheles X and Y chromosomes still display some degree of recombination with each other [28]. Thus, Ae. aegypti may be “further along” this evolutionary trajectory than previously assumed. The presence of additional repeats in our BAC assembly, which was obtained from the My1 mosquito strain, compared to the corresponding region in the AaegL5 genome assembly obtained from the Liverpool strain, suggests that the M locus may vary between strains outside of the Nix exons. Future work could investigate the population-level variation in the size and content of the M locus.

The Ae. aegypti M locus provides an intriguing example of the complexity of evolutionary forces acting on sex chromosomes, and further study of the locus will contribute to understanding the evolution of sex determination in insects and address general questions about the factors impacting gene and genome length. Importantly, these may also yield insights that can be applied to increase the efficiency of genetic strategies for vector control.

Methods

BAC library construction

A BAC library was constructed using living DH10b phage resistant Escherichia coli transfected with the pCC1BAC low copy number vector and Ae. aegypti genomic DNA from a DNA pool of approximately 50 sibling males (Amplicon Express, USA). Average insert size was 130 kb and the estimated coverage was ~5× for autosomal regions (~2.5× for sex specific regions). The male siblings were from one family from the My1 laboratory strain originating in Jinjang, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in the 1960s (described in [34]), after five generations of full-sib mating. Superpools and matrixpools were supplied to allow PCR based screening of the BAC library.

BAC library screening, isolation and sequencing

The BAC library was PCR screened using primers (Nix1F 3'-TTG AGT CTG AAA AGT CTA TGC AA-5', Nix1R 3'-TCG CTC TTC CGT GGC ATT TGA-5', Nix2F 3'-ACG TAG TCG GCA ACT CGA AG-5', Nix2R 3'-CTG GGA CAA ATC GAA CGG AA-5') based on the complete coding sequence of Nix (GenBank: KF732822). The first primer set was also used to screen for Nix in the genomic DNA of six male and six female individuals each from two wildtype Ae. aegypti strains.

Screening of the library resulted in four positive clones - two for each primer pair. These BAC clones were propagated, extracted using a Maxiprep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), pooled before SMRTbell library preparation (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA), and sequenced on a single SMRTcell using P6-C3 chemistry on the PacBio RS II platform (PacBio, USA).

Data analysis

The sequence data was trimmed to remove vector sequences and adaptors prior to assembly with the CANU v1 assembler [35], followed by sequence polishing with QUIVER.

BLASTN was used to assess the uniqueness of the assembled Nix region compared to the Aedes aegypti Liverpool reference genome AaegL3 and the newer Aag2 cell line assembly. Illumina data generated from male and female genomic DNA (accession numbers SRX290472 and SRX290470) and RNA (accession numbers SRX709698-SRX709703) were mapped to a combined reference containing the assembled Nix region added to the AaegL3 genome. DNA samples were mapped with BOWTIE 2.2.1 (using default parameters with -I 200 and -X 500) and RNA-Seq data with TOPHAT 2.1.1 version (using default parameters). RNA-Seq data was processed using the CUFFLINKS 2.2.1 pipeline to look for potential genes and male/female specific expression from the region.

Genes were predicted using AUGUSTUS and the Aedes aegypti model [15], repetitive regions described using REPEATMASKER 4.0.6 and the Ae. aegypti repeat database.

Abbreviations

- AaegL#:

-

Aedes aegypti Liverpool (LVP) strain reference genome assembly, version #

- BAC:

-

Bacterial artificial chromosome

- CRISPR/Cas9:

-

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease

- LTR:

-

Long terminal repeat

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-Seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

Laughlin CA, Morens DM, Cassetti MC, Costero-Saint Denis A, San Martin JL, Whitehead SS, et al. Dengue research opportunities in the Americas. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1121–7.

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–7.

Musso D, Cao-Lormeau VM, Gubler DJ. Zika virus: following the path of dengue and chikungunya? Lancet. 2015;386:243–4.

Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika virus in the Americas - yet another arbovirus threat. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:601–4.

Alphey L. Genetic control of mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 2014;59:205–24.

World Health Organization. Mosquito (vector) control emergency response and preparedness for Zika virus. 2016. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/news/mosquito_vector_control_response/en/ Accessed 25 Apr 2016.

Gilles JRL, Schetelig MF, Scolari F, Marec F, Capurro ML, Franz G, et al. Towards mosquito sterile insect technique programmes: exploring genetic, molecular, mechanical and behavioural methods of sex separation in mosquitoes. Acta Trop. 2014;132:S178–87.

Hoang KP, Teo TM, Ho TX, Le VS. Mechanisms of sex determination and transmission ratio distortion in Aedes aegypti. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:49.

Charlesworth D, Mank JE. The birds and the bees and the flowers and the trees: lessons from genetic mapping of sex determination in plants and animals. Genetics. 2010;186:9–31.

Craig GB, Hickey WA, Vandehey RC. An inherited male-producing factor in Aedes aegypti. Science. 1960;132:1887–9.

Clements AN. The Biology of Mosquitoes. London: Chapman & Hall; 1992.

Newton ME, Wood RJ, Southern DI. Cytological mapping of the M and D loci in the mosquito, Aedes aegypti (L.). Genetica. 1978;48:137–43.

Toups MA, Hahn MW. Retrogenes reveal the direction of sex-chromosome evolution in mosquitoes. Genetics. 2010;186:763–6.

Hall AB, Basu S, Jiang X, Qi Y, Timoshevskiy VA, Biedler JK, et al. A male-determining factor in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2015;348:1268–70.

Nene V, Wortman JR, Lawson D, Haas B, Kodira C, Tu ZJ, et al. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti. a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316:1718–23.

Koren S, Phillippy AM. One chromosome, one contig: complete microbial genomes from long-read sequencing and assembly. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:110–20.

Severson DW, Behura SK. Mosquito genomics: progress and challenges. Annu Rev Entomol. 2012;57:143–66.

Hall AB, Timoshevskiy VA, Sharakhova MV, Jiang X, Basu S, Anderson MAE, et al. Insights into the preservation of the homomorphic sex-determining chromosome of Aedes aegypti from the discovery of a male-biased gene tightly linked to the M-locus. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:179–91.

Adelman ZN, Tu Z. Control of mosquito-borne infectious diseases: sex and gene drive. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:219–29.

Matthews BJ, McBride CS, DeGennaro M, Despo O, Vosshall LB. The neurotranscriptome of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:32.

Chen X-G, Jiang X, Gu J, Xu M, Wu Y, Deng Y, et al. Genome sequence of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, reveals insights into its biology, genetics, and evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E5907–15.

Matthews BJ, Dudchenko O, Kingan S, Koren S, Antoshechkin I, Crawford JE, et al. Improved Aedes aegypti mosquito reference genome assembly enables biological discovery and vector control. bioRxiv. 2017;240747

Biedler JK, Hu W, Tae H, Tu Z. Identification of early zygotic genes in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti and discovery of a motif involved in early zygotic genome activation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33933.

Artieri CG, Fraser HB. Transcript length mediates developmental timing of gene expression across Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:2879–89.

Muller HJ. The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutat Res. 1964;1:2–9.

Charlesworth B. Evolution of sex chromosomes. Science. 1991;251:1030–3.

Kaiser VB, Bachtrog D. Evolution of sex chromosomes in insects. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:91–112.

Hall AB, Papathanos P-A, Sharma A, Cheng C, Akbari OS, Assour L, et al. Radical remodeling of the Y chromosome in a recent radiation of malaria mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2114–23.

Marais GAB, Nicolas M, Bergero R, Chambrier P, Kejnovsky E, Monéger F, et al. Evidence for degeneration of the Y chromosome in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Curr Biol. 2008;18:545–9.

Bachtrog D. Y-chromosome evolution: emerging insights into processes of Y-chromosome degeneration. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:113–24.

Carvalho AB, Dobo BA, Vibranovski MD, Clark AG. Identification of five new genes on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13225–30.

Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G. Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity (Edinb). 2005;95:118–28.

Fontaine A, Filipović I, Fansiri T, Hoffmann AA, Cheng C, Kirkpatrick M, et al. Extensive genetic differentiation between homomorphic sex chromosomes in the mosquito vector, Aedes aegypti. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:2322–35.

Lacroix R, McKemey AR, Raduan N, Kwee Wee L, Hong Ming W, Guat Ney T, et al. Open field release of genetically engineered sterile male Aedes aegypti in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42771.

Berlin K, Koren S, Chin C-S, Drake JP, Landolin JM, Phillippy AM. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:623–30.

Acknowledgments

PacBio sequencing was conducted at the Centre for Genomics Research, University of Liverpool with the assistance of Dr Margaret Hughes and Dr John Kenny. We thank Dr Andrea Betancourt and Dr Ilik Saccheri for comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) PhD training grant BB/M503460/1 (JT & ACD) and BBSRC grant BB/M001512/1 (KM & ACD).

Availability of data and materials

The assembly is available in NCBI GenBank under accession number KY849907 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KY849907). The FASTQ files for the RNA-Seq and genomic DNA reads used to map to the assembly are archived in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers SRX290472 and SRX290470 (genomic DNA) and SRX709698-SRX709703 (RNA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT, RK and AEvH contributed equally to this work. KM and ACD designed the study and obtained funding, with contribution from JT. KM provided mosquito samples. ERS and ACD commissioned the BAC library construction. AEvH and JT screened the BAC library and extracted DNA. AEvH performed BAC scaffolding. ACD oversaw sequencing and assembled the DNA sequence. RK performed the mapping and developed computational strategies for data analysis. JT performed the repeat masking. JT and ACD wrote the paper, with contribution from AEvH. JT, RK and ACD produced the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JT is a sponsored student (through the BBSRC Industrial CASE studentship) and KM is an employee of Oxitec Ltd., respectively, which therefore provided stipend or salary and other support for the research program.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Alignment of the 207 kb BAC region to the corresponding region in the AaegL5 male reference assembly. Figure S2. Alignment of the 207 kb BAC region to chromosome 1 of the AaegL5 male reference assembly. Figure S3. PCR screening of the M locus gene Nix in male and female DNA of wild type Aedes aegypti strains. Figure S4. Intron size distribution in Aedes aegypti Liverpool reference genome AaegL3. (PDF 249 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Types and abundance of repeats in the 207kb assembled M locus region and 99 kb Nix intron, identified by RepeatMasker using the Aedes aegypti repeat library. (XLSX 10 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, J., Krishna, R., van’t Hof, A.E. et al. The sequence of a male-specific genome region containing the sex determination switch in Aedes aegypti. Parasites Vectors 11, 549 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3090-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3090-3