Abstract

Background

Angiostrongylus vasorum is a nematode residing in the heart and pulmonary vessels of dogs and wild carnivores. In Europe the red fox is its reservoir, while only three records from wolves have been published. Angiostrongylus vasorum has a worldwide distribution, and many pieces of evidence demonstrate that it is spreading from endemic areas to new ones. In Italy, A. vasorum was reported with increasing frequency in dogs and foxes in the last decades, and now it is considered endemic throughout the country. Angiostrongylus vasorum can be asymptomatic or cause respiratory and circulatory disorders, at times causing severe disseminated infections.

Methods

Between February 2012 and December 2016, 25 wolves found dead in central Italy were submitted to the Istituto Zooprofilattico del Lazio e della Toscana for post-mortem examination. Samples of lungs, heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, mediastinic lymph nodes and brain were collected from each animal for histological examination. When adult and larval nematodes were microscopically seen in lungs, the other organs were processed, and five histological sections for each organ were examined. To confirm parasite identification, lung samples were submitted to a PCR-sequencing protocol targeting the ITS2 region of A. vasorum.

Results

Seven wolves (28.0%) harboured nematode larvae in lung sections. In two of the positive wolves, adult nematodes were visible in pulmonary arteries, in four animals larvae were also detected in other organs. DNA sequencing reactions confirmed parasite identification as A. vasorum in all the cases.

Conclusions

As a result of the high prevalence of A. vasorum reported in wolves in the present study, a focus of high circulation could be hypothesised in central Italy. Nevertheless, the similarly high prevalence in foxes originating from the same areas were reported in previous papers. Histopathological evidence highlights the pathogenic potential of A. vasorum in the wolf, especially in juvenile animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adult Angiostrongylus vasorum (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) reside in the heart and pulmonary vessels of dogs and many wild carnivore species [1,2,3]. Terrestrial gastropods, slugs and snails are the intermediate hosts [1]. In Europe, the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is considered the natural reservoir of this parasite [1, 4, 5]. Angiostrongylus vasorum has a worldwide distribution, and many pieces of evidence point out that it is spreading from endemic areas to new ones [6,7,8,9]. In Italy, A. vasorum was first reported over 20 years ago in red foxes, and since then it has been reported with increasing frequency in dogs and foxes, and now it is considered endemic throughout the country [10, 11].

In the different host species, A. vasorum infection can be asymptomatic or cause respiratory and circulatory disorders [12, 13], at times causing disseminated infections of various severity [5, 14,15,16].

In the last few decades, the wolf (Canis lupus) has undergone a population recovery in Europe, thanks to legal protection and changes in human attitudes [17]. In Italy in particular, this recovery has been noticeable, and the wolf has expanded its distribution from small, isolated populations to the whole country, almost everywhere ecological conditions are suitable [18, 19]. Diseases are considered possible issues in the conservation of wild carnivores, particularly when spillover of pathogens between domestic and wild canids occurs [20, 21], but at present limited data have been published on the health status and parasite fauna of wolves in Europe and Italy.

At present, only three records of A. vasorum from wolves have been published [16, 22, 23]. Hence, in the above-described scenario, it was considered advisable to report new data regarding this parasite infection in this host, reporting a prevalence value and describing the more relevant histopathological findings.

Methods

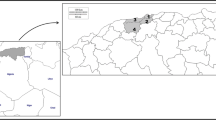

Between February 2012 and December 2016, 25 wolves (13 males and 12 females) found dead in Lazio Region (central Italy) (Fig. 1) were submitted to the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Lazio e della Toscana “M. Aleandri” for post-mortem examination. To ascertain if they were pure wolves or hybrids with the dog, 18 autosomal microsatellite markers were used to genotype each of the 25 animals [24]. The age of each animal was estimated trough teeth wear examination [25] in two classes, 10 being juveniles < 12 months and 15 adults > 12 months.

For histological exams, three samples of lungs and a sample of heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, mediastinic lymph nodes and brain were collected from each animal and fixed in buffered formalin. All lung samples were embedded in paraffin wax and 5 thin sections, stained with haematoxylin and eosin, were prepared for each sample and examined under a microscope. When adult and larval nematodes were microscopically seen in lung samples, the other organs previously fixed in formalin were processed as described above and 5 histological sections for each organ were examined with the aim of evaluating larval dissemination. To confirm parasite identification, lungs of all the wolves with adult nematodes or larval forms in lungs were subjected to a PCR-sequencing protocol, using the primers NC1 and NC2, as described by Gasser et al. [26]. Obtained sequences were compared with those available in the GenBank using the BLASTn tool.

Results

No genetic admixture with dogs for any of the 25 wolves was found. Seven wolves (28.0%) harboured nematode larvae in lung sections. In two of these, adult nematodes were visible in pulmonary arteries in lung sections (Fig. 2), and in 4 animals larvae were also detected in other organs (Table 1). Due to the previous report of A. vasorum in wolves from the same study area [16], anatomical localisation of adult worms in pulmonary vessels and finding of nematode larvae and histopathological changes in one of the examined organs led to the suspicion of an A. vasorum infection. DNA sequencing reactions, performed on 7 PCR positive samples, resulted in sequences roughly 480 bp in length. BLASTn analysis for all 7 sequences showed an identity of 99% (query coverage of 100%) with the ITS2 region of A. vasorum (GenBank: EU627597.1), confirming parasite identification (Table 1). Overall, A. vasorum prevalence was 38.5% among male specimens and 16.7% among female ones and 40.0% among juvenile wolves and 20.0% among adult ones.

At necropsy, all 7 positive wolves showed fatal traumatic lesions, with multiple bone fractures, and it was possible to ascertain that they all died due to fatal injuries. In Wolves 1, 4 and 6 a few congested and small consolidated areas were present in the pulmonary diaphragmatic lobes. Lungs of Wolf 2 showed several extensive areas of reddish-brown coloration with increased consistency in the diaphragmatic lobes and foci of pleural fibrosis with adhesions to the parietal pleura. In Wolf 3, only a whitish and firm pulmonary nodular lesion was seen. No gross changes were detected in lungs of wolves 5 and 7, as well as in any of the other organs of all seven wolves.

Microscopically, parasitic pulmonary lesions were represented by small and scattered or confluent granulomatous foci, with lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, granulocytes and a few multinucleated giant cells surrounding eggs or parasitic larvae. In Wolf 2, extensive areas of lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic pneumonia associated with necrosis and eggs and larval debris were seen. In Wolves 4 and 6, one or more adult worms were detected in pulmonary arteries (Fig. 2), frequently associated to organised thrombi. Larvae were also observed (Table 1) in 2 out of 7 kidneys, in glomerular capillaries or inside small cortical granulomas (Fig. 3a), in meningeal and encephalic vessels (Fig. 3b), in 1 out of 7 brains and in a subcapsular lymphatic sinus in 1 out of 7 mediastinic lymph nodes. In these cases, mild to moderate lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with few eosinophils accompanied the presence of the larvae. In some animals, despite no larvae were observed, small lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates with few eosinophils were seen in sections of different organs, brain and kidney in particular (Table 1). In the brain, mild to moderate flogosis was multifocally present in the leptomeninges and occasionally as perivascular cuffings in cerebral parenchyma. The kidney showed mild interstitial nephritis; inflammatory cells were sometimes located around the glomeruli or as small inflammatory nodules in the renal cortex.

Discussion

When considering the lack of previous reports of A. vasorum in the wolf, the prevalence reported in the present study (28.0%) is surprisingly high. Two of the three previous reports of this host/parasite association were case reports [16, 22], not reporting prevalence values. The only previous prevalence reported in the literature is 3.1% [23] in Croatian wolves. Nevertheless, the two prevalence values are hardly comparable, due to the different techniques adopted. Hermosilla et al. [23] detected A. vasorum larvae from wolf faecal samples using the sodium acetate-acetic acid formalin technique and, as stated by the same Authors, this technique is not the most sensitive for the detection of lungworm larvae in faeces, thus their prevalence may be underestimated. The prevalence reported in the present study could be considered more realistic, due to the objectivity of recovering parasites at post mortem examination and the confirmation of their identification via molecular assays. Nevertheless, as adopted necropsy procedures were not specifically aimed at A. vasorum detection (i.e. pulmonary arteries were not systematically opened), false negatives can’t be ruled out. At present, A. vasorum in the wolf have been reported in a wide geographical range, from Spain on the west to Croatia to the east, indicating that the wolf should be considered one of the natural hosts of this nematode in Europe. Lack of reports from other areas are probably ascribable to the low wolf populations present in most of the geographical range of this species in Europe [27] and, in general, to the low number of wolves investigated for parasites.

As an alternative explanation for the high prevalence reported in the present study, a focus of high A. vasorum circulation should be hypothesised in the areas of central Italy from where the wolves originated. Nevertheless, Eleni et al. [11] reported a similarly high prevalence (43.5%) in foxes originating from the same areas, possibly indicating that natural areas of central Italy would be particularly favourable to this parasite. Moreover, considering the whole study area (Fig. 1), it is possible to pinpoint a cluster of positive animals in a restricted area northeast of Rome, an area probably characterised by environmental and climatic conditions (milder temperatures, higher humidity) particularly favourable to gastropods intermediate hosts of A. vasorum [28, 29].

Although low numbers did not allow any statistical analysis, interesting is the difference in prevalence recorded among adult and juvenile wolves and among female and male ones. In dogs higher levels of infection are recorded in young animals [7, 30], possibly due to an incomplete development of the immune system and to the inquisitive attitude of younger dogs, making more probable the ingestion of slugs or snails [12, 30]. Our results fit with these findings in dogs, with juvenile wolves showing a prevalence (40.0%) exactly twice as high compared to adults (20.0%). Regarding sex, we found a prevalence of A. vasorum in male wolves (38.5%) more than twice that in female ones (16.7%). In the literature, no gender predisposition to A. vasorum infection is reported [7] and among 20 dogs found infected in central Italy [31], exactly 50% were males and 50% females. In accordance with our results in wolves, only Chapman et al. [12] reported a higher percentage of male dogs (73.9%) among 23 animals found infected in England.

Angiostrongylus vasorum is known to be (at times) highly pathogenic in dogs [32] and to be able to cause significant pathology in foxes [11]. Hence, this parasite could be considered a potential health issue in regions where it is endemic, and wolves are of conservation concern. Histopathological evidence reported in the present study, consistent with the pathological findings previously reported in wolves [16], confirm the pathogenic potential of A. vasorum in this species, especially in juvenile animals, although the death of these wolves was ascribable to fatal injuries.

References

Morgan ER, Shaw SE, Brennan SF, De Waal TD, Jones BR, Mulchay G. Angiostrongylus vasorum: a real heartbreaker. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:49–51.

Jefferies R, Shaw SE, Viney ME, Morgan ER. Angiostrongylus vasorum from South America and Europe represent distinct lineages. Parasitology. 2009;136:107–15.

Jefferies R, Shaw SE, Willesen J, Viney ME, Morgan ER. Elucidating the spread of the emerging canid nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum between Palearctic and Nearctic ecozones. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10:561–8.

Bolt G, Monrad J, Henriksen P, Dietz HH, Koch J, Bindseil E, et al. The fox (Vulpes vulpes) as a reservoir for canine angiostrongylosis in Denmark. Acta Vet Scand. 1992;33:357–62.

Denk D, Matiasek K, Just FT, Hermanns W, Baiker K, Herbach N, et al. Disseminated angiostrongylosis with fatal cerebral haemorrhages in two dogs in Germany: a clinical case study. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:100–8.

Traversa D, Guglielmini C. Feline aelurostrongylosis and canine angiostrongylosis: a challenging diagnosis for two emerging verminous pneumonia infections. Vet Parasitol. 2008;157:163–74.

Koch J, Willesen JL. Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: an update. Vet J. 2009;179:348–59.

van Doorn DCK, van de Sande AH, Nijsse ER, Eysker M, Ploeger HW. Autochthonous Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs in the Netherlands. Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:163–6.

Hurníková Z, Miterpáková M, Mandelík R. First autochthonous case of canine Angiostrongylus vasorum in Slovakia. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:3505–8.

Traversa D, Di Cesare A, Meloni S, di Regalbono AF, Milillo P, Pampurini F, et al. Canine angiostrongylosis in Italy: occurrence of Angiostrongylus vasorum in dogs with compatible clinical pictures. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:2473–80.

Eleni C, Grifoni G, Di Egidio A, Meoli R, De Liberato C. Pathological findings of Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Central Italy, with the first report of a disseminated infection in this host species. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1247–50.

Chapman PS, Boag AK, Guitina J, Boswood A. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in 23 dogs (1999–2002). J Small Anim Pract. 2004;45:435–40.

Conboy GA. Canine angiostrongylosis: the French heartworm: an emerging threat in North America. Vet Parasitol. 2011;176:382–9.

Negrin A, Cherubini GB, Steeves E. Angiostrongylus vasorum causing meningitis and detection of parasite larvae in the cerebrospinal fluid of a pug dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2008;49:468–71.

Lepri E, Veronesi F, Traversa D, Conti MB, Marchesi MC, Miglio A, et al. Disseminated angiostrongylosis with massive cardiac and cerebral involvement in a dog from Italy. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:505–8.

Eleni C, De Liberato C, Azam D, Morgan ER, Traversa D. Angiostrongylus vasorum in wolves in Italy. Int J Parasitol: Paras Wildl. 2014;3:12–4.

Boitani L. Wolf conservation and recovery. In: Mech LD, Boitani L, editors. Wolves: behaviour ecology and conservation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003. p. 317–40.

Lucchini V, Galov A, Randi E. Evidence of genetic distinction and long-term population decline in wolves (Canis lupus) in the Italian Apennines. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:523–36.

Galaverni M, Caniglia R, Fabbri E, Lapalombella S, Randi E. MHC variability in an isolated wolf population in Italy. J Hered. 2013;104:601–12.

Craft ME, Volz E, Packer C, Meyers LA. Distinguishing epidemic waves from disease spillover in a wildlife population. Proc R Soc London B. 2009;276:1777–85.

Alexander KA, McNutt JW, Briggs MB, Standers PE, Funston P, Hemson G, et al. Multi-host pathogens and carnivore management in southern Africa. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;33:249–65.

Segovia JM, Torres J, Miguel J. Helminths in the wolf, Canis lupus, from north-western Spain. J Helminthol. 2001;75:183–92.

Hermosilla C, Kleinertz S, Silva LMR, Hirzmann J, Huber D, Kusak J, et al. Protozoan and helminth parasite fauna of free-living Croatian wild wolves (Canis lupus) analysed by scat collection. Vet Parasitol. 2017;233:14–9.

Lorenzini R, Fanelli R, Grifoni G, Scholl F, Fico R. Wolf-dog crossbreeding: “smelling” a hybrid may not be easy. Mamm Biol. 2014;79:149–56.

Landon DB, Waite CA, Peterson RO, Mech LD. Evaluation of age determination techniques for gray wolves. J Wildl Manag. 1998;62:674–82.

Gasser RB, Chilton NB, Hoste H, Beveridge I. Rapid sequencing of rDNA from single worms and eggs of parasitic helminths. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2525–6.

Chapron G. Wolf - Europe summary. In: Kaczensky P, Chapron G, Von Arx M, Huber D, Andrén H, Linnell J, editors. Status, management and distribution of large carnivores - bear, lynx, wolf and wolverine - in Europe. European Commission; 2012. p. 40–53.

Barutzki D, Schaper R. Natural infections of Angiostrongylus vasorum and Crenosoma vulpis in dogs in Germany (2007–2009). Parasitol Res. 2009;105:39–48.

Taubert A, Pantchev N, Vrhovec MG, Bauer C, Hermosilla C. Lungworm infections (Angiostrongylus vasorum, Crenosoma vulpis, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus) in dogs and cats in Germany and Denmark in 2003–2007. Vet Parasitol. 2009;159:175–80.

Morgan ER, Jefferies R, van Otterdijk L, McEniry RB, Allen F, Bakewell M, Shaw SE. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs: presentation and risk factors. Vet Parasitol. 2010;173:255–61.

Tieri E, Pomilio F, Di Francesco G, Saletti MA, Totaro P, Troilo M, et al. Angiostrongylus vasorum in 20 dogs in the province of Chieti, Italy. Vet It. 2011;47:77–88.

Ferdushy T, Hasan MT. Angiostrongylus vasorum: the “French heartworm”. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:765–71.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. A representative sequence is submitted to the GenBank database under the accession number EU627597.1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CD identified parasites in tissue sections and wrote the manuscript. CE identified parasites in tissue sections, described pathological findings and wrote the manuscript. PC wrote the manuscript. RM examined histological sections. RL performed molecular identification of parasites. PR analysed geographical distribution of wolves. GC, CC, AM, FS and GB performed necropsies and described macroscopic lesions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

De Liberato, C., Grifoni, G., Lorenzetti, R. et al. Angiostrongylus vasorum in wolves in Italy: prevalence and pathological findings. Parasites Vectors 10, 386 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2307-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2307-1