Abstract

Background

Taxonomic identification of ticks obtained during a longitudinal survey of the critically endangered marsupial, Bettongia penicillata Gray, 1837 (woylie, brush-tailed bettong) revealed a new species of Ixodes Latrielle, 1795. Here we provide morphological data for the female and nymphal life stages of this novel species (Ixodes woyliei n. sp.), in combination with molecular characterisation using the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1). In addition, molecular characterisation was conducted on several described Ixodes species and used to provide phylogenetic context.

Results

Ixodes spp. ticks were collected from the two remaining indigenous B. penicillata populations in south-western Australia. Of 624 individual B. penicillata sampled, 290 (47%) were host to ticks of the genus Ixodes; specifically I. woyliei n. sp., I. australiensis Neumann, 1904, I. myrmecobii Roberts, 1962, I. tasmani Neumann, 1899 and I. fecialis Warburton & Nuttall, 1909. Of these, 123 (42%) were host to the newly described I. woyliei n. sp. In addition, 268 individuals from sympatric marsupial species (166 Trichosurus vulpecula hypoleucus Wagner, 1855 (brushtail possum), 89 Dasyurus geoffroii Gould, 1841 (Western quoll) and 13 Isoodon obesulus fusciventer Gray, 1841 (southern brown bandicoot)) were sampled for ectoparasites and of these, I. woyliei n. sp. was only found on two I. o. fusciventer.

Conclusions

Morphological and molecular data have confirmed the first new Australian Ixodes tick species described in over 50 years, Ixodes woyliei n. sp. Based on the long-term data collected, it appears this tick has a strong predilection for B. penicillata, with 42% of Ixodes infections on this host identified as I. woyliei n. sp. The implications for this host-parasite relationship are unclear but there may be potential for a future co-extinction event. In addition, new molecular data have been generated for collected specimens of I. australiensis, I. tasmani and museum specimens of I. victoriensis Nuttall, 1916, which for the first time provides molecular support for the subgenus Endopalpiger Schulze, 1935 as initially defined. These genetic data provide essential information for future studies relying on genotyping for species identification or for those tackling the phylogenetic relationships of Australian Ixodes species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tick species within the genus Ixodes Latreille, 1795 (Ixodidae) have a worldwide distribution and can be found on a variety of hosts including mammals, birds, and occasionally reptiles. Species of Ixodes that generally command the greatest importance are those that are potential pathogens either directly as a cause of anaemia/blood loss or paralysis, and/or indirectly as a vector for disease. The role of ticks as vectors for disease has been the dominant area of research in recent times and many pathogenic protozoan, bacterial and viral agents have been isolated from a range of Ixodes species [1–4]. While the vectorial significance of ticks is well established, there are still many unknowns with respect to the genetic diversity, species delimitation and host distribution of ticks, particularly in wildlife. Recent studies using both morphological and molecular tools have confirmed new tick species from bats, wild boar, peccary, opossums, lizards and foxes [5–9], emphasizing the potential for new discoveries in wildlife populations.

Australian fauna are host to a large number of tick species, many of which are endemic to the Australasian region. Within the Australian lineage of the genus Ixodes there are currently 22 known species, with the latest species being described in 1962 [10–12]. The Australian tick descriptions provided by Roberts [12] remain the cornerstone of taxonomic identification even today, but due to the lack of sufficient specimens available at that time it is very likely that there are undiscovered tick species and unknown host associations.

The ability to discover either new tick species or new host records is greatly enhanced when longitudinal research is conducted on a large number of hosts. Such research has recently been undertaken on the critically endangered marsupial, Bettongia penicillata Gray, 1837 (Potoroidae) (woylie, brush-tailed bettong), of which indigenous populations are now restricted to the south-western corner of Australia. Investigations into rapid population declines experienced by this marsupial commenced in 2006 and are still ongoing [13–15]. Parasite infections were considered a possible contributing factor to these population declines and hence during this ten year period comprehensive ecto- and endoparasite data have been accumulated. Large numbers of ticks were also collected from many individual hosts from a range of other species throughout a range of seasonal conditions over this period.

Taxonomic identification of ticks obtained from trapped B. penicillata revealed a new Ixodes species first detected in 2007 [15] and again following the longitudinal surveillance of several populations from 2014 to 2016 [16]. Morphologically, this unidentified tick was similar to Ixodes species within the subgenus Endopalpiger Schulze, 1935 as described by Roberts [12], of which four species had been described, Ixodes victoriensis Nuttall, 1916, I. australiensis Neumann, 1904, I. tasmani Neumann, 1899 and I. hydromyidis Swan, 1931. Indeed, initial identification of this tick using dichotomous keys developed by Roberts [12] indicated this tick was I. victoriensis, a tick that to date has only been found on wombats and potoroos in Victoria and Tasmania [17]. However, this identification was considered to be incorrect due to significant differences observed between the two species particularly the shape of the scutum, palpal article 1, and spurs on the coxae. These same morphological differences were also recently highlighted by Weaver [17], who examined four specimens labelled as I. victoriensis kept at the Australian National Insect Collection (ANIC). These specimens had been collected from B. penicillata in western Australia, but due to geographical location and subsequent redescription, Weaver [17] considered these to be a misidentification.

Here, we provide morphological data for the female and nymphal life stages of this novel Ixodes species, in combination with molecular characterisation using the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1). Due to minimal genetic information available for Australian Ixodes species, molecular characterisation was also conducted on several described species and used to provide phylogenetic context. The conservation implications for this novel Ixodes species, which appears to have a predilection for an endangered marsupial as a host, are also considered.

Methods

Tick collection and morphological identification

Ixodes spp. ticks were collected from 2006 to 2016 from the two remaining indigenous B. penicillata populations in south-western Australia (Dryandra Woodland and the Upper Warren Region), and a translocated population near Perth (Karakamia Wildlife Sanctuary) (Fig. 1). Ticks were also collected from sympatric species in Dryandra Woodland and the Upper Warren, including Trichosurus vulpecula hypoleucus Wagner, 1855 (koomal, brush tail possum), Dasyurus geoffroii Gould, 1841 (chuditch, western quoll) and Isoodon obesulus fusciventer Gray, 1841 (quenda, southern brown bandicoot). The tick collection held at Murdoch University Parasitology Section Museum was also scrutinized for unidentified Ixodes spp. that could potentially belong to the new tick species. Specimens of I. victoriensis currently held at ANIC were obtained for morphological comparisons. All tick specimens were preserved in 70% ethanol and later identified using keys developed by Roberts [12].

Morphometric data were based on 12 adult female specimens (four unfed, seven partially fed and one engorged) and 14 nymph specimens (nine unfed, four fed and one engorged). To date male specimens of the new species have not been collected. All except two nymphs were collected from B. penicillata located in the Dryandra Woodland and the Upper Warren region and one animal housed at Perth Zoo. The two exceptions were museum specimens collected from Macrotis lagotis Reid, 1837 (greater bilby) housed at Kanyana Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre Perth W.A. Measurements (in millimetres unless indicated otherwise) were taken from specimens temporarily mounted on slides. Selected specimens were cleared in lactophenol for photographing with line drawings done to scale from these images.

Six specimens were also prepared for observation by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Samples were fully dehydrated in 100% anhydrous ethanol and critical point dried, before being mounted on stubs with carbon tape and coated with ~20 nm gold. All imaging was done at 10–15 kV on a Zeiss field emission SEM.

DNA extraction

Adult female and nymph specimens identified as the new Ixodes species were chosen for molecular characterisation, along with specimens identified as I. australiensis, I. tasmani, I. victoriensis, I. myrmecobii and I. fecialis. Ethanol-preserved ticks were rehydrated in a series of decreasing ethanol concentrations. Specifically specimens were successively placed for 1 h each in 50%, 30% and 10% ethanol with the final hour in 100% dH20. Following rehydration, specimens were roughly dissected with fresh disposable scalpel blades before being frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground as finely as possible. All specimens were then digested with proteinase K overnight at 56 °C before DNA extraction using the Maxwell® 16 instrument (Promega, Madison, USA) or with the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Hilden, Germany).

PCR amplification and sequencing

All tick specimens were amplified by PCR at the cox1 gene with minor modifications from a previously described protocol [18]. PCR reactions were performed in 25 μl volumes consisting of 1–2 μl of extracted DNA, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1× reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCL, pH 8.5 at 25 °C, 50 mM KCl), 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.4 μM of each primer, and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Fisher Biotec, Perth, Australia). Amplification conditions for cox1 involved a denaturing step of 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 45 s, 50–51 °C for 60 s and 72 °C for 60 s, followed by a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified using an Agencourt AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, USA) and sequence reactions were performed using the Big Dye Terminator Version 3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were electrophoresed on an ABI 3730 96 capillary machine.

Phylogenetic analyses

Resultant sequences were compared with available published sequences on GenBank using the basic alignment search tool (BLAST) with further analysis of sequence alignments conducted in Sequencher® V5.2.4 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, USA). Additional sequences retrieved from GenBank representing I. holocyclus Neumann, 1899 (AB075955, HM545841), I. cornuatus Roberts, 1960 (KM821527, HM545846), I. hirsti Hassall, 1931 (KM821524), I. fecialis, (FJ571509), I. uriae White, 1852 (NC006078) and Rhipicephalus sanguineus Latrielle, 1806 (JX416308) were included in the phylogenetic analyses conducted in MEGA7 [19]. Phylogenetic trees were inferred with the neighbour-joining method, with a bootstrapping of 1,000 replicates and evolutionary distances calculated using the Kimura 2-parameter method [20, 21]. In addition analyses were conducted using the maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony methods [22].

Results

Detection of Ixodes spp.

Of 624 individual B. penicillata sampled between 2006 and 2016, 290 (47%) were host to ticks of the genus Ixodes. Of these, 123 (42%) were host to the new species described below (Table 1). In addition, 268 individuals of sympatric species (166 T. v. hypoleucus, 89 D. geoffroii and 13 I. o. fusciventer) were sampled for ectoparasites and of these, the new species was found on two I. o. fusciventer (Table 1). Within the museum collection held at Murdoch University, additional specimens of the new species were identified from five individual B. penicillata and one M. lagotis. Further information regarding the hosts of these museum specimens was not available.

Family Ixodidae Dugés, 1834

Genus Ixodes Latreille, 1795

Ixodes woyliei n. sp

Type-host: Bettongia penicillata Gray, 1837 (Potoroidae) (woylie, brush-tailed bettong).

Other hosts: Isoodon obesulus fusciventer Shaw, 1797 (Peramelidae) (quenda, southern brown bandicoot) and Macrotis lagotis Reid, 1837 (Peramelidae) (greater bilby).

Type-locality: Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia, Australia (32°47'S, 116°58'E).

Other localities: Karakamia Wildlife Sanctuary, Western Australia, Australia (31°48'S, 116°15'E) and the Upper Warren Region, Western Australia, Australia (34°21'41"S, 116°18'22"E).

Type-specimens: Holotype: female ex B. penicillata, Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia, Australia (32°47'S 116°58'E), December 2015, deposited at the West Australian Museum (WAM T142602). Paratypes: Total 25, 11 females and 14 nymphs ex B. penicillata. Eight females (P1–P8) collected from Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia, Australia (32°47'S, 116°58'E), June 2016 (P1, P2, P7, P8), September 2015 (P3, P4), February 2015 (P5, P6); 2 females (P9, P10) collected from Karakamia Wildlife Sanctuary, Western Australia, Australia (31°48'S, 116°15'E) July 2006; and one female (P11) collected from the Upper Warren Region Western Australia, Australia (34°21'41"S, 116°18'22"E). Seven nymphs (P12–P18) collected from Upper Warren Region, Western Australia, Australia (34°21'41"S, 116°18'22"E) September 2014 and December 2014, 4 nymphs (P19–P22) collected from Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia, Australia (32°47'S, 116°58'E), September 1994 and October 1993, one (P23) collected from Perth Zoo and two (P23–25) collected from Kanyana Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre, Perth. Seven paratype specimens (P1, P2, P7, P8, P15–P17) have been deposited at the Australian National Insect Collection (ANIC 48-006275 – ANIC 48-006277) and five paratype specimens (P9, P10, P12–P14) have been deposited at the Western Australian Museum (WAM T142603-WAM T142604).

Representative DNA sequences: Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1): GenBank accession numbers KX673875–KX673881.

ZooBank registration: Details of Ixodes woyliei n. sp. have been submitted to ZooBank and the Life Science Identifier (LSID) for the article is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1DB97319-FF74-4380-9D49-988BA3467342 and LSID for the new name is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:7FC91916-ACBC-4832-8788-19CCBB8EF7B1.

Etymology: The species name Ixodes woyliei refers to the common name of the host B. penicillata (commonly known as the woylie) for which this tick appears to have a high predilection. Woylie is the Aboriginal name given by the Noongar people who live in the south-west corner of Western Australia [23].

Description

General. Golden brown medium-sized ticks with greatly enlarged palpal article 1, over crowded hypostome dentition mainly 6/6 and 5/5, coxae all armed with strong pointed spurs, and anal groove open posteriorly.

Female. Idiosoma (Fig. 2): Unfed specimens oval and elongate, widest just posteriorly of spiracles. Body length measured dorsally from midway between scapular points to most posterior margin range from 2.4–3.3, width 1.4–2.2 (Fig. 2a). Partially fed specimens length range from 3.3–5.3, width 1.9–2.5, engorged specimens attaining length 11, width 6.5. Dorsal setae are short (<25 μm), lay within a uniform moderate covering of shallow punctations, marginal grooves are well defined. The scutum about as long as wide, widest point posterior to mid-length, anterolateral and posterolateral margins are mildly sinuous with posterior angle broadly rounded, lateral carinae present (Figs. 2c and 5c). Scutal length range from 1.2–1.5, width 1.2–1.6. Punctations are shallow and moderate in number, becoming coarser in cervical grooves, lateral rugae and along the posterior margin; scutal setae are minute (<8 μm). Cervical grooves well defined anteriorly becoming shallow posteriorly and extending to, or almost to the scutal margin. Scapulae are large and bluntly pointed. Ventral setae are longer than dorsal (<40 μm) with two rows of longer setae (>40 μm) around the lateral side of the spiracular plate. Genital aperture is level with the anterior margin of coxa III, but moving towards second intercoxal space on engorgement (Fig. 2b). Spiracular plates suboval, length 0.16–0.30, with approximately 3–4 rows of goblets, macular eccentric (Fig. 4b). Anal groove is horseshoe shaped, rounded anteriorly, curving gently and convergently posteriorly but becoming slightly divergent near body margin and remaining widely open (Fig. 2d). Both the internal and external margin of the anal groove epicutical surface possess several rows of inward facing spines, overlapping across the divide of the anal groove and running laterally for most of its length. This feature has not been mentioned previously but appears to be typical for all Ixodes species that we have been able to examine.

Gnathosoma (Fig. 3) Basis dorsally, short, 0.36–0.60 in length by 0.40–0.55 in width. Length measurement taken from top of the palpi to the posterior margin of the cornua. Dorsal basis capituli subrectangular, with one median depression and a lateral depression on each side, the depressed areas being separated by carinae, posterior margin slightly undulating with small indistinct cornua (Figs. 3a and 5b). Porose areas large, suboval, lying in lateral depressions, widely separated by the median depression. Basis ventrally about as long as wide with small but distinct auriculae. Palps short and article 1 greatly enlarged, extending inwardly to partially ensheathe base of mouthparts, ventrally with a strong posterolateral salience. Articles 2 and 3 are without apparent suture, total length 0.29–0.35, width 0.07–0.15 (Figs. 3b and 5a). Hypostome length ranges from 0.17–0.33, width 0.15–0.17, spatulate, broad anteriorly, with sharply pointed large denticles, mainly 6/6 and 5/5. Dentition formula essentially 12/12 of small over crowded denticles at the corona, dropping in number but increasing in size to 6/6 and 5/5 by anterior third and reducing to 4/4, 3/3 with crenulations running down to the base (Fig. 3c).

Legs (Fig. 4): Slender and moderate length. Coxa I transversely elongate with a strong pointed external spur. Coxae II, III, and IV somewhat square with progressively smaller pointed external spurs, all coxae with few setae, syncoxae absent (Figs. 4a and 5f). Length of tarsus I 0.3–0.5 with few long setae (<50 μm) and some small (<20 μm) (Figs. 4c and 5d, e). Haller’s organ, anterior pit suboval with seven sensilla arranged in a cluster in the centre, posterior capsule opening slightly above the pit and divided by a low ridge with up to five sensilla seen within (Fig. 4d). Length of tarsus IV is 0.4–0.5.

Nymph. Idiosoma (Fig. 6): Unfed specimens oval and elongate, widest about mid length between coxae III and IV, well-defined marginal grooves and minute dorsal setae (<10) within uniformly scattered punctations (Fig. 6a). Body length measured dorsally from midway between the scapular points to most posterior margin range from 1.3–1.6, width range 0.78–1.1. Fed specimen length range from 1.7–2.2, width 0.97–1.6, with engorged specimens attaining length 4.0, width 2.0. Scutum wider than long, with posterior angle broadly rounded, lateral carinae present (Figs. 6c and 9c). Scutal length ranges from 0.52–0.63, width 0.63–0.75. Punctations are shallow and moderate in number, becoming coarser in cervical grooves, lateral rugae and along the posterior margin; scutal setae are minute (<8 μm). Cervical grooves are well defined anteriorly becoming shallow posteriorly and extending to, or almost to the scutal margin. Scapulae are large and bluntly pointed. Ventral setae are slightly longer than dorsal mostly (<15 μm) with some longer setae (>20 μm) around the spiracular plate (Fig. 6b). Spiracles suboval, length 0.095–0.10, width 0.065–0.12 with c.3–4 rows of goblets covering the whole surface (Fig. 8b). Anal groove is horseshoe shaped, rounded anteriorly, curving gently and convergently posteriorly but becoming slightly divergent near body margin and remaining widely open (Fig. 6d). Both the internal and external margin of the anal groove epicutical possess several rows of inward facing spines as seen in the adult female.

Gnathosoma (Fig. 7): Basis dorsal length measurement taken from the top of the palpi to the posterior margin of the basis, length 0.19–0.26, width 0.22–0.26 in width. Dorsal basis capituli subrectangular, posterolateral angles roundly pointed (Figs. 7a ad 9b). Basis ventrally rounded posteriorly with small auriculae. Palps short and article 1 greatly enlarged, extending inwardly to partially ensheathe base of mouthparts, ventrally with a strong posterolateral salience. Articles 2 and 3 without apparent suture total length 0.15–0.17 by width 0.055–0.080 (Figs. 7b and 9a). Hypostome length ranges from 0.13–0.17, width 0.065–0.130, spatulate, broad anteriorly, with sharply pointed denticles, mainly 3/3. Dentition formula essentially 6/6 small denticles at corona then decreasing in number, but increasing in size to 4/4 followed by about 8 rows of 3/3 (Fig. 7c).

Legs (Fig. 8): Slender and of moderate length. Coxa I transversely elongate with a strong pointed external spur. Coxae II, III, and IV somewhat square with progressively smaller pointed external spurs, all coxae with few setae, syncoxae absent (Figs. 8a and 9d). Length of tarsus I 0.22–0.30 with few long setae (<40 μm) and some minute (<10 μm) (Fig. 8c). Haller’s organ, anterior pit suboval with seven sensilla arranged in a cluster in the centre, posterior capsule opening slightly above the pit and divided by a low ridge with at least four sensilla visible (Fig. 8b). Length of tarsus IV is 0.20–0.30.

Differential diagnosis

Morphologically, I. woyliei logically conforms to the subgenus Endopalpiger as described by Roberts [12] due to the enlarged palpal article 1 that extends inwardly to partially ensheathe the base of the mouthparts; common to all females within this subgenus. However it is also pertinent to consider the species of Exopalpiger Schulze, 1935 (I. fecialis, I. vestitus Neumann, 1908 and I. antechini Roberts, 1960) as more recently the species of these two subgenera have been amalgamated into Exopalpiger [24]. The species of these two subgenera however can be quite easily differentiated by the palpal article 1 which in Exopalpiger species is enlarged but does not extend inwardly, as seen in I. woyliei n. sp. and the other Endopalpiger species. Further morphological differences are outlined in Table 2. Differentiation of adult females from the other four Endopalpiger species can be achieved by the presence of an open anal groove, the large pointed spurs on each coxa, presence of syncoxae, the large number of denticles on the hypostome, and the shape of the scutum (Table 2). Specifically, the presence of an open anal groove, the lack of syncoxae and greater dentition differentiates I. woyliei n. sp. from I. australiensis, while the presence of spurs on the coxae (armed) differentiates I. woyliei n. sp. from I. tasmani and I. hydromyidis, both of which lack spurs. The most morphologically similar species to I. woyliei n. sp. is I. victoriensis; however these two species can be readily differentiated by dentition and the shape of the scutum, spurs on the coxae, and palpal article 1. Ixodes woyliei n. sp. has a remarkable and complex dentition with small overcrowded denticles at the corona (12/12), dropping in number but increasing in size to mainly a 6/6 and 5/5 dentition whereas I. victoriensis dentition is mostly 5/5, with rows of 4/4 at both anterior and posterior ends [17]. The shape of the scutum in I. woyliei n. sp. is longer than that of I. victoriensis (about as long as wide vs wider than long for I. woyliei), and appears more angular. The coxae of I. woyliei n. sp. are all armed with large, pointed spurs and lack syncoxae, while I. victoriensis coxae are armed with smaller spurs that are not as pointed and possess syncoxae. The enlarged palpal article 1 described for I. woyliei n. sp. has a posterolateral prominence making it more widely rectangular than that seen on I. victoriensis.

Differential diagnosis of the nymphal stage can be largely achieved as for the adult female (Table 2). A minor exception involves I. australiensis whereby the nymph has an anal groove which remains open, but not as widely as seen in I. woyliei nymphs. However the shape of palpal article one, spurs and presence of syncoxae allow differentiation.

Molecular characterisation

Cox1 gene sequences were obtained for 27 Ixodes spp. ticks; eight I. woyliei n. sp., eight I. australiensis, five I. tasmani, two I. victoriensis, two I. fecialis and two I. myrmecobii (Table 3). All available life-stages for each species were successfully amplified and sequenced. Sequence alignment of the ~800 bp product revealed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) ranging from zero within I. victoriensis to 32 within I. woyliei, although the small sample sizes for some species make this variation in SNPs difficult to interpret.

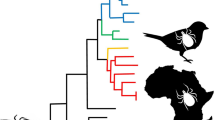

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted with all sequences obtained from this study, along with available published sequences for I. holocyclus, I. cornuatus, I hirsti, I. uriae, I fecialis and Rhipicephalus sanguineus. This allowed for four of the five subgenera within the Australasian Ixodes spp., as described by Roberts [12], to be represented; namely Endopalpiger, Exopalpiger, Sternalixodes Schulze, 1935 and Ceratixodes Neumann, 1902. Trees constructed using neighbour-joining, maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony methods gave a similar topology, hence only the NJ tree is presented here (Fig. 10). The trees displayed consistency in placement of I. woyliei n. sp. as a sister species of I. victoriensis and in clustering with I. australiensis and I. tasmani; all Endopalpiger species. Similarly, the sequences generated from I. myrmecobii specimens consistently clustered with the other species representing the subgenus Sternalixodes, I. holocyclus, I. cornuatus and I. hirsti. Generated sequences for I. fecialis, representing the subgenus Exopalpiger, matched the published sequence (FJ571509) but due to lack of genetic material for other Exopalpiger species a grouping was not conclusive.

Phylogenetic relationships of isolates of Ixodes woyliei n. sp. with other Australasian Ixodes spp. as estimated using cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene sequences. Sequences with accession numbers were obtained from GenBank, all others were generated in this study. Evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method supported with bootstrap test of 1,000 replicates (values > 50% shown). Rhipicephalus sanguineus is used as the outgroup

Discussion

Molecular confirmation of I. woyliei n. sp.

The molecular data generated for I. woyliei n. sp. conclusively supports the taxonomy, with I. woyliei positioned in a monophyletic group with the other Endopalpiger species for which genetic data were obtained, namely I. australiensis, I. tasmani and I. victoriensis. This also provides the first molecular support for the subgenus Endopalpiger. The close morphological relationship between I. woyliei n. sp. and I. victoriensis is also supported genetically, with the two positioning as sister species within this monophyletic grouping. Interestingly, the positioning of the one species of Exopalpiger genotyped, I. fecialis, does not support the monophyletic grouping of Endopalpiger and Exopalpiger as per Camaicas [24] but that of Roberts [12]. However, more genetic data are required to confirm or deny these taxonomic groupings and would require further research.

Genetically it appears that I. woylie n. sp. is a distinct species, but it is also necessary to consider the presence/absence of genetic exchangeability between groups to be confident of species status [25, 26]. Ixodes woyliei, I. australiensis and I. tasmani are sympatric, sharing the same geographical region, habitat and host; yet they remain genetically distinct. This would infer a lack of genetic exchange and therefore distinct species. This is not the case with I. woyliei n. sp. and I. victoriensis, which are separated by geography; I. victoriensis is found only in eastern Australia (Victoria and Tasmania) and I. woyliei only in the south west region of Western Australia, a distance of approximately 3,500 km. This geographical separation reflects the current allopatric distribution of the primary hosts for these species: Vombatus ursinus (the common wombat) for I. victoriensis and B. penicillata for I. woyliei. Until recently, however, these hosts were quite possibly sympatric species. Bettongia penicillata was once the most common and widest ranging of all potoroids covering most of southern Australia, but by the 1970’s was extinct from all regions except the south-western corner of Australia [27]. Theoretically, prior to European settlement genetic exchangeability should have been possible but is not evident in these results, again providing support for species status.

Molecular characterisation has been used extensively both to confirm tick species and to further our understanding of the phylogenetic relationships within various genera [7, 18, 28–32]. To achieve this, commonly used genetic markers have included the 12S and 16S ribosomal DNA, nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2, and the mitochondrial cox1 gene. A recent paper assessing the effectiveness of these genetic markers concluded the cox1 gene was the most successful for tick species [33] and certainly the present study found this gene to be successful in unambiguously distinguishing between Australian Ixodes species.

Host-parasite ecology

Based on the long-term data collected, it appears this tick has a strong predilection for B. penicillata, with 42% of Ixodes infections identified as I. woyliei n. sp. The two exceptions included two I. o. fusciventer and one M. lagotis, which may represent the ability for this novel species to use alternate sympatric hosts, or perhaps these represent accidental hosts. The I. o. fusciventer observation was made during early sympatric trapping sessions at Karakamia Wildlife Sanctuary in 2006; however I. woyliei was not detected in subsequent trappings of I. o. fusciventer, within two indigenous B. penicillata populations (Dryandra Woodland and the Upper Warren Region). In addition, a recent study investigating parasitism in urban populations of I. o. fusciventer that were not sympatric with B. penicillata sampled 287 individuals and I. woyliei was not detected (Hillman, pers. com.). Less information is available regarding the M. lagotis finding, except that this animal was located in an animal rehabilitation centre that was also known to frequently house B. penicillata. Whether there was a chance of enclosure contamination between these two hosts is speculative, but remains a possibility. Although the sample size for I. o. fusciventer is low and not all sympatric marsupial species (e.g. kangaroos) were sampled, the results suggest that B. penicillata is the preferred host for this tick. This apparent host preference displayed by I. woyliei n. sp. may be explained by an ecological link between a nidiculous tick species and a nest dwelling host. Bettongia penicillata individuals utilise several nests, normally located under grass trees (Xanthorrhea spp.), throughout their home range [34]. Transmission could largely be confined to B. penicillata if ticks detach, undergo development, and relocate to another host within these refuge sites. Depending on the frequency of nest sharing between alternate host species, of which I. o. fusciventer is most ecologically similar [35], this tick may simply be influenced by host specificity to these nests. The nidiculous nature of the new tick species may also explain the absence of male specimens detected from hosts, if mating occurs within nests with minimal time spent on the host.

The vectorial capacity of this novel tick species is unknown. Of particular concern for B. penicillata is the transmission of trypanosomes (protozoan blood parasites), which have been implicated in the recent population declines of this host [36, 37]. However, the Trypanosoma species (T. copemani and T. vergrandis) detected in B. penicillata have also been detected in other marsupials, suggesting that a generalist vector is responsible [38–42]. Ixodes woyliei n. sp. would not be considered a generalist tick and therefore less likely to be the vector for these blood parasites.

When considering the critically endangered status of B. penicillata, having undergone a 90% decline in seven years [13], and the apparent host specificity of I. woyliei, there is a very real risk of a future co-extinction event. Despite the recent dramatic decline in B. penicillata numbers, the data presented here suggest I. woyliei is maintaining a strong connection to B. penicillata. Co-extinction is of increasing importance as we discover more about wildlife host-parasite relationships and the possible flow-on effects these events can cause [43, 44]. Also of consideration for this tick species is the risk of extinction through translocation events. Bettongia penicillata is currently the focus of intense conservation management strategies involving the frequent and wide scale translocation of this species across Australia [45]. Some translocation protocols involve deliberate treatment for parasites (commonly with Ivermectin; [16]) with ticks often eliminated at the point of translocation [46].

If hosts are not treated, the ability of the tick population to establish in a new host population can be reliant on the number of ticks and hosts translocated [47], and suitability of the new ecological habitat for survival during off-host development phases. Within this study the Karakamia Wildlife Sanctuary site consists of a translocated B. penicillata population that also hosts I. woyliei, suggesting these ticks can survive translocation under the right conditions. Whether this tick is able to adapt to a wider geographical region (outside south-western Australia) or is restricted to a specific ecological biome is unknown but in some cases ticks have been found to have a narrower range in habitat than their host [48]. More research is required to understand how the ecology of I. woyliei n. sp. is influencing this strong host association, and what importance this new tick has for its critically endangered marsupial host.

Conclusions

Morphological and molecular data have confirmed the first new Australian Ixodes tick species described in over 50 years, Ixodes woyliei n. sp. which has a high predilection for the critically endangered marsupial B. penicillata. The implications for this host-parasite relationship are unclear but there may be potential for a future co-extinction event. In addition, new molecular data have been generated for I. australiensis, I. tasmani and I. victoriensis and for the first time molecular support has been provided for the subgenus Endopalpiger, as initially described by Roberts [12]. These genetic data may also provide essential information for future studies relying on genotyping for species identification or for those tackling the phylogenetic relationships of Australian Ixodes species.

Abbreviations

- ANIC:

-

Australian National Insect Collection

- cox1:

-

cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene

- WAM:

-

Western Australian Museum

References

Piesman J, Sinsky RJ. Ability of Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) to acquire, maintain, and transmit Lyme disease spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi). J Med Entomol. 1988;25(5):336–9.

Fukunaga M, Takahashi Y, Tsuruta Y, Matsushita O, Ralph D, McClelland M, Nakao M. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Borrelia miyamotoi sp. nov., isolated from the ixodid tick Ixodes persulcatus, the vector for Lyme disease in Japan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1995;45(4):804–10.

Adelson ME, Rao R-VS, Tilton RC, Cabets K, Eskow E, Fein L, et al. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, Bartonella spp., Babesia microti, and Anaplasma phagocytophila in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected in Northern New Jersey. J Clin Micriobiol. 2004;42(6):2799–801.

Attoui H, Stirling JM, Munderloh UG, Billoir F, Brookes SM, Burroughs JN, et al. Complete sequence characterization of the genome of the St Croix River virus, a new orbivirus isolated from cells of Ixodes scapularis. J Gen Virol. 2001;82(4):795–804.

Apanaskevich DA, Apanaskevich MA. Description of two new species of Dermacentor Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae) from Oriental Asia. Syst Parasitol. 2016;93(2):159–71.

Hornok S, Görföl T, Estók P, Tu VT, Kontschán J. Description of a new tick species, Ixodes collaris n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae), from bats (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae, Rhinolophidae) in Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):1.

Nava S, Mangold AJ, Mastropaolo M, Venzal JM, Oscherov EB, Guglielmone AA. Amblyomma boeroi n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae), a parasite of the Chacoan peccary Catagonus wagneri (Rusconi) (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) in Argentina. Syst Parasitol. 2009;73(3):161–74.

Estrada-Peña A, Nava S, Petney T. Description of all the stages of Ixodes inopinatus n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae). Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014;5(6):734–43.

Krawczak FS, Martins TF, Oliveira CS, Binder LC, Costa FB, Nunes PH, et al. Amblyomma yucumense n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae), a parasite of wild mammals in southern Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2015;52(1):28–37.

Roberts F. Ixodes (Sternalixodes) myrmecobii sp. n. from the numbat Myrmecobious fasciatus fasciatus Waterhouse, in western Australia (Ixodidae). Aust J Entomol. 1962;1(1):42–3.

Barker SC, Walker AR, Campelo D. A list of the 70 species of Australian ticks; diagnostic guides to and species accounts of Ixodes holocyclus (paralysis tick), Ixodes cornuatus (southern paralysis tick) and Rhipicephalus australis (Australian cattle tick); and consideration of the place of Australia in the evolution of ticks with comments on four controversial ideas. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44(12):941–53.

Roberts FSH. Australian Ticks. Melbourne: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation; 1970.

Wayne AF, Maxwell MA, Ward CG, Vellios CV, Wilson I, Wayne JC, Williams MR. Sudden and rapid decline of the abundant marsupial Bettongia penicillata in Australia. Oryx. 2015;49(01):175–85.

Wayne AF, Maxwell MA, Ward CG, Vellios CV, Ward BG, Liddelow GL, et al. Importance of getting the numbers right: quantifying the rapid and substantial decline of an abundant marsupial, Bettongia penicillata. Wildl Res. 2013;40(3):169–83.

Wayne A. Progress report of the Woylie Conservation Research Project: diagnosis of recent woylie (Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi) declines in south-western Australia: a report to the Department of Environment and Conservation Corporate Executive. Kensington, WA: Department of Environment and Conservation; 2008.

Northover AS, Godfrey SS, Lymbery AJ, Morris K, Wayne AF, Thompson RCA. Evaluating the effects of ivermectin treatment on communities of gastrointestinal parasites in translocated woylies (Bettongia penicillata). EcoHealth. 2015;1-11. [Epub ahead of print].

Weaver H. Redescription of Ixodes victoriensis Nuttall, 1916 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) from marsupials in Victoria, Australia. Syst Appl Acarol. 2016;21(6):820–9.

Chitimia L, Lin R-Q, Cosoroaba I, Wu X-Y, Song H-Q, Yuan Z-G, Zhu X-Q. Genetic characterization of ticks from southwestern Romania by sequences of mitochondrial cox1 and nad5 genes. Exp Appl Acarol. 2010;52(3):305–11.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–4.

Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16(2):111–20.

Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–25.

Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics: Oxford University Press; 2000

Abbott I. Aboriginal names of mammal species in south-west Western Australia. CALMscience. 2001;3(4):433–86.

Camicas JL, Hervy JP, Adam F, Morel PC. [The ticks of the world. Nomenclature, described stages, hosts, distribution (Acarida, Ixodidia)]. Paris: Orstom Editions Publisher; 1998. (In French).

Crandall KA, Bininda-Emonds OR, Mace GM, Wayne RK. Considering evolutionary processes in conservation biology. Trends Ecol Evol. 2000;15(7):290–5.

Templeton AR. The meaning of species and speciation: a genetic perspective. In: Otte D, Endler JA, editors. Speciation and its Consequences. Sinauer Associates; 1989;3-27.

Claridge AW, Seebeck JH, Rose R. Bettongs, potoroos and the musky rat-kangaroo: CSIRO Publishing; 2007

Mitani H, Takahashi M, Masuyama M, Fukunaga M. Ixodes philipi (Acari: Ixodidae): phylogenetic status inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene sequence comparison. J Parasitol. 2007;93(3):719–22.

Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Black WC. Comparison of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S ribosomal DNA genes in resolving phylogenetic relationships among hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1999;92(1):117–29.

Song S, Shao R, Atwell R, Barker S, Vankan D. Phylogenetic and phylogeographic relationships in Ixodes holocyclus and Ixodes cornuatus (Acari: Ixodidae) inferred from COX1 and ITS2 sequences. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41(8):871–80.

Beati L, Keirans JE. Analysis of the systematic relationships among ticks of the genera Rhipicephalus and Boophilus (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 12S ribosomal DNA gene sequences and morphological characters. J Parasitol. 2001;87(1):32–48.

Crampton A, McKay I, Barker S. Phylogeny of ticks (Ixodida) inferred from nuclear ribosomal DNA. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26(5):511–7.

Lv J, Wu S, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Feng C, Yuan X, et al. Assessment of four DNA fragments (COI, 16S rDNA, ITS2, 12S rDNA) for species identification of the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):1.

Christensen P. Biology of Bettongia penicillata Gray, 1837, and Macropus eugenii (Desmarest, 1817) in relation to fire. Bulletin of the Woods and Forests Department of Western Australia. 1980;90:1–90.

Broughton S, Dickman C. The effect of supplementary food on home range of the southern brown bandicoot, Isoodon obesulus (Marsupialia: Peramelidae. Aust J Ecol. 1991;16(1):71–8.

Smith A, Clark P, Averis S, Lymbery A, Wayne A, Morris K, Thompson R. Trypanosomes in a declining species of threatened Australian marsupial, the brush-tailed bettong Bettongia penicillata (Marsupialia: Potoroidae). Parasitology. 2008;135(11):1329–35.

Thompson CK, Wayne AF, Godfrey SS, Thompson RA. Temporal and spatial dynamics of trypanosomes infecting the brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata): a cautionary note of disease-induced population decline. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):1.

Thompson CK, Botero A, Wayne AF, Godfrey SS, Lymbery AJ, Thompson RA. Morphological polymorphism of Trypanosoma copemani and description of the genetically diverse T. vegrandis sp. nov. from the critically endangered Australian potoroid, the brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata (Gray, 1837). Parasit Vectors. 2013;6(1):1.

McInnes L, Hanger J, Simmons G, Reid S, Ryan U. Novel trypanosome Trypanosoma gilletti sp. (Euglenozoa: Trypanosomatidae) and the extension of the host range of Trypanosoma copemani to include the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Parasitology. 2011;138(01):59–70.

Austen J, Jefferies R, Friend J, Ryan U, Adams P, Reid S. Morphological and molecular characterization of Trypanosoma copemani n. sp. (Trypanosomatidae) isolated from Gilbert’s potoroo (Potorous gilbertii) and quokka (Setonix brachyurus). Parasitology. 2009;136(07):783–92.

Botero A, Thompson CK, Peacock CS, Clode PL, Nicholls PK, Wayne AF, et al. Trypanosomes genetic diversity, polyparasitism and the population decline of the critically endangered Australian marsupial, the brush tailed bettong or woylie (Bettongia penicillata). Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2013;2:77–89.

Noyes H, Stevens J, Teixeira M, Phelan J, Holz P. A nested PCR for the ssrRNA gene detects Trypanosoma binneyi in the platypus and Trypanosoma sp. in wombats and kangaroos in Australia 1. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29(2):331–9.

Colwell DD, Otranto D, Stevens JR. Oestrid flies: eradication and extinction versus biodiversity. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25(11):500–4.

Gómez A, Nichols E. Neglected wild life: parasitic biodiversity as a conservation target. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2013;2:222–7.

Morris K, Page M, Kay R, Renwick J, Desmond A, Comer S, et al. Forty years of fauna translocations in Western Australia: lessons learned. Advances in Reintroduction Biology of Australian and New Zealand Fauna. 2015;217

Durden LA, Keirans JE. Host-parasite coextinction and the plight of tick conservation. Am Entomol. 1996;42(2):87–91.

Moir ML, Vesk PA, Brennan KE, Poulin R, Hughes L, Keith DA, et al. Considering extinction of dependent species during translocation, ex situ conservation, and assisted migration of threatened hosts. Conserv Biol. 2012;26(2):199–207.

Kolonin G. Mammals as hosts of ixodid ticks (Acarina, Ixodidae). Entomol Rev. 2007;87(4):401–12.

Acknowledgments

We thank Colin Ward, Marika Maxwell, Chris Vellios, and other Parks and Wildlife staff along with Sarah Keatley and numerous Murdoch University volunteers for their assistance with the collection of these specimens. We also thank Lyn Kirilak for technical assistance in preparing SEM samples and the use of the jointly funded (University, and State and Commonwealth Governments) Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research Facility at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation & Analysis, The University of Western Australia. We would also like to thank Russell Hobbs for valuable advice and feedback on the morphometric data presented.

Funding

The samples included in this study were collected as a part of the larger Woylie Conservation Research Project and its components that were variously funded by the Department of Parks and Wildlife (WA), state (Natural Resource Management, Western Australia) and federal [Caring for Our Country and the Australian Research Council (LP 130101073 and LP 0775356)] government-funded projects, and as a part of the Woylie Disease Investigation Project.

Availability of data and material

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. All molecular data generated in this study have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers KX673858–KX673883. The type-material is submitted to ANIC (accession numbers ANIC48-006275–ANIC48-0077) and WAM (accession numbers WAM T14602–WAM T14604).

Authors’ contributions

AA, AE and AT conceived and designed the tick identification study, AW, AT, AL, HB, YA, AN, SG and KM designed the broader woylie study, AW, HB, AN and SG undertook field work and sample collection AE, HB,YA and AA identified collected tick specimens, AE and PC undertook morphological imaging and provided morphometric data, AA conducted genetic characterisation and drafted the manuscript with input from all co-authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

All trapped animals were managed and handled using procedures formally approved by the Murdoch University Animal Ethics Committee (AEC numbers: NS11852-06; W2172-08, W2350-10 and RW 2659) and Department of Parks and Wildlife Animal Ethics Committee (AEC numbers: DPaW DECAEC 8/2006, 52/2009 and 57/2012) in compliance with the Australian Code of Practice for the use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ash, A., Elliot, A., Godfrey, S. et al. Morphological and molecular description of Ixodes woyliei n. sp. (Ixodidae) with consideration for co-extinction with its critically endangered marsupial host. Parasites Vectors 10, 70 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-1997-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-1997-8