Abstract

Background

The genus Spelaeomyia includes four African species considered as being cavernicolous: Spelaeomyia darlingi, Spelaeomyia mirabilis, Spelaeomyia emilii and Spelaeomyia moucheti. Despite a potential role in Leishmania major leishmaniasis transmission in Mali, no molecular studies and only few morphological studies have addressed relationships between species of Spelaeomyia.

Methods

Specimens of Sa. moucheti were collected in two different sites in Gabon. Spelaeomyia emilii and Sa. darlingi specimens came from Gabon and Mali. Specimens of Sa. mirabilis were collected in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Gabon. All specimens were caught using CDC miniature light traps, then dissected, both heads and genitalia were kept for morphological analysis and the rest of the bodies were kept for molecular processing and analyses.

Results

Some unidentified males are associated to Sa. moucheti females using molecular tools and are described for the first time. A new morphological feature is observed on the spermathecae of the female and new drawings are provided. For the first time a phylogenetic analysis is carried out on rDNA and mtDNA markers and it shows that Sa. moucheti is the sister species of Sa. mirabilis.

Conclusions

Spelaeomyia moucheti is the sister species of Sa. mirabilis. This result is in agreement with the sharing of morphological characters between these closely related species. Moreover, these two species are not as cavernicolous as literature previously indicated. They were caught in open rainforest in Gabon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Spelaeomyia Theodor was created as a subgenus of Sergentomyia França & Parrot [1] and defined as a strictly cavernicolous group of phlebotomine sand flies. It was erected at the generic level by Artemiev during a revision of the classification of Phlebotominae [2] and then commonly considered by systematicians at this taxonomic level [3–6].

The genus includes four species, all recorded in sub-Saharan continental Africa [7]: Spelaeomyia darlingi (Parrot & Wanson, 1939) designated as the type-species of the genus, Sa. mirabilis (Kirk & Lewis, 1954), Sa. emilii (Vattier-Bernard, 1966) and Sa. moucheti (Vattier-Bernard & Abonnenc, 1967). This genus has been under-studied despite the possible role of its species in Leishmania major leishmaniasis transmission in Mali [8] possibly due to their supposed cavernicolous ecology and trophic specialization on bats.

Our sampling includes all the known species of the genus. In order to assess the taxonomic relationships among members of the genus Spelaeomyia, we carried out a molecular phylogeny based on ribosomal and mitochondrial markers.

Methods

Sand fly sampling

The different specimens used in our study come from various sampling projects. We had access to Sa. mirabilis during a project of molecular systematics. An epidemiological study in Mali [9] allowed us to collect some Sa. darlingi. Furthermore, it was during a recent faunistic research project aimed at the study of the Culicinae fauna of Gabon that we caught some Sa. mirabilis, Sa. emilii, females of Sa. moucheti and unknown males. All specimens were collected using CDC Miniature Light Trap incandescent lights (John W. Hock Company, Gainesville, Florida, USA) from dusk to dawn outside caves and on a 24-h basis inside caves.

Preparation of samples for morphological study

The sand flies were preserved in 100 % ethanol and then the whole carcasses (thoraces, wings and legs) were kept for molecular studies, while heads and genitalia were dissected and mounted in Euparal after different successive baths: 2 h in 10 % potassium hydroxide; 2 h in distillated water; 10 h in a Marc-André solution [7]; 10 h in distillated water; 20 min in 70 % ethanol; 20 min in 90 % ethanol; 20 min in 100 % ethanol; and 10 h in a beech wood solution. The spermathecae of the Sa. moucheti females were first removed from the abdomen and then observed with a simple clearing of heated Marc-André solution (90 °C).

Specimens were observed using BX 53 (Olympus, Japan) and Leica DM2000 microscopes. Measurements (in micrometers unless otherwise indicated) were taken using the Stream motion software (Olympus, Japan) and a video camera (Leica and Olympus, respectively) connected to the microscope. The figures were drawn by hand using a drawing tube connected to the microscope.

Sequencing

In the manuscript, we call “Cyt b” a part of the cytochrome b gene, the complete sequence of tRNA-Ser gene and a part of the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 gene. Genomic DNA was extracted from the thoraces, wings, legs and abdomens of individual sand flies using the QIAmp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and modified by crushing sand fly tissues with a piston pellet (Treff, Switzerland), and using an elution volume of 200 μl.

mtDNA amplifications were performed in a 50 μl volume using 5 μl of extracted DNA, 50 pmol of each of the primers, 10 mM of Tris HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 50 mM of KCl, 0.01 % of Triton X 100, 200 μM of dNTP and 1.25 units of Taq polymerase (5 prime, Germany). The cycle profiles were marker dependent. Each PCR began by an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 3 min and ended with a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. Amplification of a fragment of cytochrome b (Cyt b) gene was done by using the primers N1N-PDR: (5′-CA(T/C) ATT CAA CC(A/T) GAA TGA TA-3′) and C3B-PDR: (5′-GGT A(C/T)(A/T) TTG CCT CGA (T/A)TT CG(T/A) TAT GA-3′) following the method previously published [10]: 5 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 40 °C for 60 s and extension at 68 °C for 60 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 44 °C for 60 s and extension at 68 °C for 60 s.

The D1 and D2 fragments of the 28S rDNA were amplified using the primer couple C1′: 5′-ACC CGC TGA ATT TAA GCA T-3′ and D2: 5′-TCC GTG TTT CAA GAC GGG-3′ following the thermal profile: 30 cycles with 1 min 94 °C, 1 min 58 °C, 1 min 68 °C using the primers [11]. The D8 domain of the 28S rDNA was amplified using the primers C7′ (5′-GTG CAG ATC TTG GTG GTA GT-3′) and D8E (5′-GCT TTG TTT TAA TTA AAC AGT-3′) following the thermal profile: 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 48 °C for 40 s and extension at 68 °C for 90 s [12].

Amplicons were analysed by electrophoresis in 1.5 % agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Direct sequencing in both directions was performed using the primers used for DNA amplification. The correction of sequences was done using the programmes Pregap and Gap included in the Staden Package [13].

Molecular analyses

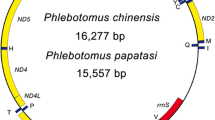

Phlebotomus papatasi, Sergentomyia schwetzi and Sergentomyia boironis were selected as outgroups because the phylogenetical position of the genus Spelaeomyia is doubtful and the selected species belong to two different genera: Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia. Sergentomyia schwetzi is widespread in Africa whereas Se. boironis is endemic from Madagascar. Moreover, sequences for these species were available for each molecular marker.

Sequence alignments were performed using the ClustalW routine included in the Bioedit software [14] and checked “by eye” in order to respect the three following criteria: (i) minimize the number of inferred mutations (number of steps); (ii) prefer substitution to insertion-deletion; and (iii) prefer transitions over transversions, because they have a higher probability of occurrence [15–17].

The molecular datasets were analysed by Bayesian methods with MrBayes 3.2 [18]. Trees were rooted with a sequence for Ph. papatasi (specimen code Ph-papatasi-HM992927) as outgroup. One partition for each codon position of the mitochondrial gene (Cyt b) and one partition for the nuclear genes D1D2 and D8 were implemented to explore the best substitution model, individually and concatenated. The best-fit models of nucleotide substitutions were selected with jModelTest v2.1.4 [19] using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Bayesian analyses were carried out independently for each gene and for the concatenated data (2 million generations, saving trees every 100 generations). The first 25 % of the generated trees were discarded as 'burn-in’. The robustness of trees nodes was assessed by clade posterior probability values (CPP).

Results

Molecular analyses

The origin of the specimens of this study and their accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

We performed three analyses: the first with the mitochondrial gene with 402 aligned base pairs (bp), the second with all 1,266 bp nuclear genes (662 for D1D2 and 604 for D8) and a third combined-data analysis of all the molecular data with 1,668 bp.

The symmetrical model with a gamma distributed among-site variation (SYM + G) was indicated as the best-fit model for the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. The general time reversible model with gamma distributed among-site rate variation (GTR + G) was indicated as the best-fit model for both separated and concatenated 28S rDNA markers (D1, D2 and D8). The GTR + G + I model was indicated as the best-fit model for concatenated mtDNA and rDNA.

Trees from Bayesian inference analyses of the concatenated-data, mtDNA, and rDNA are summarized in Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Most nodes of the topologies obtained from concatenated genes (rDNA and Cyt b) are well supported with CPP values comprised between 83 and 100 %. Based on the analyses on both, the rDNA and Cyt b genes, Sa. mirabilis and Sa. moucheti appeared as sister species. However, the positioning of Sa. emilii remained problematic. At first, based on rDNA markers (Fig. 1), Sa. darlingi and Sa. emilii appeared to be sister species. However, in the Cyt b sequences, Sa. darlingi clearly diverged and Sa. emilii ultimately appeared as the sister group of Sa. mirabilis and Sa. moucheti (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, conflict of these discordant nodes is strongly supported by both data types. This strongly supported conflict is resolved in favour of the rDNA in the combined-data tree (Fig. 3).

The newly-generated sequences from the males and females of Sa. moucheti were identical for each marker.

Description of the male of Spelaeomyia moucheti

Locality : La Lopé National Park, Mikongo and Lékédi private park, Bakoumba, Gabon 2013, CDC Light trap.

Voucher material : MIK2, MIK35, MIK141, GAB27, GAB65, and GAB88.

[Measurements based on six specimens; minimum and maximum values are indicated.]

Head (Fig. 4): Interocular suture incomplete. Cibarium with 8–10 teeth arranged on concave arc directed backwards and without denticles. Pigmented patch absent. Pharynx fine, c.200 long, slightly shrunk backwards. Pharyngeal armature not well developed, with some wrinkles and very small denticles. Palpal formula 1-4-2-3-5; third palpal article with about 10 club-like Newstead spines. Ascoid formula: 2/III-XV; ascoids rather long but not going over next articulation; base of ascoid pointing backwards (Fig. 4d). A III (= flagellomere I) 372–385, A IV (= flagellomere II) 222–225, A V (= flagellomere III) 227, A III < A IV + A V; labrum 215–240 μm. A III/labrum = 1.60–1.73. Labial furca closed.

Thorax (Fig. 5d): Wing length 1,998–2,140, width 560–600, length/width ratio 3.55–3.57; α = 432–452; β = 318–328; δ = 95–100; ɣ = 250–300; wing width/ɣ 2.0–2.24; π = 350–360.

Genitalia (Fig. 5): Coxite 414–433 long, bearing a basal lobe on its internal face; basal lobe with about twenty strong setae. Coxite/lateral lobe ratio 7.4–7.9. Style rather long and straight, reducing apically, 247–256, bearing two spines: one terminal and one subterminal. One seta at last third of style present. Paramere simple, 210–240 in total length. Surstyle 449–477 long. Penis short, 47–56, triangular, heavily sclerotized. Genital pump heavily sclerotized, well developed, 194–212. Genital ducts short, 253–286, relatively wide, enlarged at the top.

Updates on the morphology of the female of Spelaeomyia moucheti

It appeared important to us to make a new illustration (Fig. 6a) of the female spermathecae to update those from the original description [20]. The structure of the spermathecae was elucidated due to the application of Marc-André clearing. The spermathecal ducts are fused at their base and the walls of the spermathecae are more sclerotized on the sides than on the apex. Herein we also describe a new morphological feature on the spermathecal ducts that are slightly striate at the apex, just before the bulbous process of the spermathecae. In Fig. 6b the bulbous process of the spermathecae overlapping the apex of the spermathecal duct is illustrated (specimen mounted in Euparal).

Updates on the ecology of samples collected in Gabon

Genus Spelaeomyia is known to be strictly cavernicolous, but in Gabon we collected Sa. mirabilis only in the rainforest, Sa. moucheti, in both habitats (but in greater number outside caves) and Sa. emilii only in caves.

Discussion

Spelaeomyia has been defined as a group of cavernicolous sand flies, according to the following characters [1]: style with two spines of which one is terminal and with a small seta; process with long hairs near the base of the coxite; penis sheet rudimentary; genital filaments short and thick with terminal process; legs very long; cibarial armature consisting of a row of long pointed teeth; pharynx unarmed; spermathecae irregularly crinkled sack.

Lewis & Kirk [21] redefined later the genus Spelaeomyia as follows: several erect hairs on the second to sixth abdominal tergites; style with one or two spines and a small seta; a paired process, with short hairs, and a median process between bases of coxites; penis sheath of unusual shape, either very short and blunt or very long and pointed; penis filament with a flat hyaline process near tip; legs very long; buccal cavity with no more than 14 principal teeth some of them widely separated; a sensory papilla on antennal segments III, IV and V; pharynx unarmed; spermathecae irregularly crinkled sack.

This definition needs to be modified: (i) the males of Sa. darlingi and Sa. emilii exhibit only one distal spine on the style and their coxal setae cannot be considered as a spine in our opinion; (ii) Sa. darlingi has long genital filaments; (iii) the penis of Sa. darlingi is long and pointed. Moreover, the females are characterized by their sensorial trough (translation of the French “dépression sensorielle” used by French-speaking authors observing this structure) at the distal part of the abdomen, first observed in Sa. mirabilis [22] and then confirmed in all species of the genus Spelaeomyia [7]. The ecological data also need to be modified. Based on literature [7, 22–24], the genus Spelaeomyia is strictly cavernicolous. In our prospections in Gabon, Sa. emilii was indeed exclusively collected in caves. However, Sa. mirabilis was only recorded in rainforest biotopes. Spelaeomyia moucheti were found in caves but they were mainly collected in rainforests. Therefore, it is wrong to consider Sa. mirabilis and Sa. moucheti as strictly cavernicolous species.

The unknown males are considered and described as those of Sa. moucheti because: (i) they were captured with females of Sa. moucheti, the same day, in the same traps; (ii) both belong to the same genus, and we suppose, to the same species; and (iii) the mtDNA cytochrome b, rDNA D1D2 and D8 sequences obtained from these males and from Sa. moucheti females are exactly similar. With the description of the male of Sa. moucheti, we propose an identification key to the species of Spelaeomyia based on male morphology:

-

1

Style with one spine (terminal) ........................................ 2

Style with at least two spines (one terminal, one subterminal) ....................................................................... 3

-

2

Paramere simple, blunt ending; coxal setae directly on the coxite; genital filaments short .................... Sa. emilii

Paramere rounded at the top, with a superior finger-like process at the middle; coxal setae on a long process; genital filaments long .......................................... Sa. darlingi

-

3

Paramere with a tuft of grouped setae at the top; genital ducts with a process at the end ..................... Sa. mirabilis

No tuft of setae at the top of the paramere; genital ducts without a process but apically widened .............................................................................. Sa. moucheti

We strongly consider Sa. moucheti as the sister species of Sa. mirabilis whereas the position of Sa. darlingi and Sa. emilii as sister species was not resolved. If we look for morphological characters, Sa. moucheti and Sa. mirabilis share long ascoids reaching the next articulation and exhibit two spines on the style and a short penis. Here, the morphological characters are in agreement with the results from analyses of molecular markers. Spelaeomyia darlingi and Sa. emilii share only one spine on the style and have relatively short ascoids.

Strongly supported conflicts (for which conflicting clades are strongly supported by each type of data) tend to be uncommon and may be resolved in favor of either mtDNA or nucDNA in almost equal frequency. Combined analyses of mtDNA and nucDNA are common [25], but the consequences of combining these data are largely unexplored. This trend is somewhat unsettling given that the use of mtDNA is somewhat controversial, and given the possibility that mtDNA might dominate combined analyses due to larger numbers of variable characters [25].

Conclusions

The description of the male of Sa. moucheti is proposed and supported by molecular homologies with females. An update on the morphology of the female of Sa. moucheti is made and advice is given on the observation of spermathecae. Molecular and morphological data showed that Sa. moucheti is closely related to Sa. mirabilis. A new identification key for species of Spelaeomyia is proposed based on male morphology. New ecological data suggest that the genus Spelaeomyia is not strictly cavernicolous and some of its members are adapted to various environments. Additional studies regarding taxa in sand flies, particularly for the species of the genus Spelaeomyia, remain necessary. A study of the consequences of combining nuclear and mitochondrial data for phylogenetic analysis would be required as well.

Abbreviations

CIRMF, Centre International de Recherches Médicales de Franceville; Cyt b, in the manuscript, we call “Cyt b” a part of the cytochrome b gene, the complete sequence of tRNA-Ser gene and a part of the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 gene; IRD, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement; Sa, Spelaeomyia; Se, Sergentomyia

References

Theodor O. Classification of the old world species of the subfamily Phlebotominae (Diptera: Psychodidae). Bull Ent Res. 1948;39:85–118.

Artemiev M. A classification of the subfamily Phlebotominae. Parassitologia. 1991;33(suppl):69–77.

Galati E. Phlebotominae (Diptera, Psychodidae) Classificação, Morfologia, Terminologia e Identificação de Adultos. Apostila. Bioecologia e Identificação de Phlebotominae. Vol. I. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2013.

Galati EAB. Phylogenic systematics of Phlebotominae (Diptera, Psychodidae) with emphasis of American groups. Biol Dir Malariol y San Amb. 1995;35 Suppl 1:133–42.

Léger N, Depaquit J. Systématique et biogéographie des Phlébotomes (Diptera: Psychodidae). Ann Soc Entomol France. 2002;38(n.s):163–75.

Marcondes CB. A proposal of generic and subgeneric abbreviations for phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) of the World. Entomol News. 2007;118:351–6.

Abonnenc E. Les phlébotomes de la région éthiopienne (Diptera, Psychodidae). Cah ORSTOM. Sér Ent Méd Parasitol. 1972;55:239.

Berdjane-Brouk Z, Kone AK, Djimde AA, Charrel RN, Ravel C, Delaunay P, et al. First detection of Leishmania major DNA in Sergentomyia (Spelaeomyia) darlingi from cutaneous leishmaniasis foci in Mali. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28266.

Berdjane-Brouk Z, Charrel RN, Hamrioui B, Izri A. First detection of Leishmania infantum DNA in Phlebotomus longicuspis Nitzulescu, 1930 from visceral leishmaniasis endemic focus in Algeria. Parasitol Res. 2012;111(1):419–22.

Esseghir S, Ready PD, Killick-Kendrick R, Ben-Ismail R. Mitochondrial haplotypes and geographical vicariance of Phlebotomus vectors of Leishmania major. Insect Mol Biol. 1997;6(3):211–25.

Randrianambinintsoa FJ, Leger N, Robert V, Depaquit J. Paraphyly of the subgenus Sintonius (Diptera, Psychodidae, Sergentomyia): status of the Malagasy species. Creation of a new subgenus and description of a new species. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98065.

Depaquit J, Léger N, Randrianambinintsoa FJ. Paraphyly of the subgenus Anaphlebotomus and creation of Madaphlebotomus subg. nov. (Phlebotominae: Phlebotomus). Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29(2):159–70.

Bonfield J, Staden R. Experiment files and their application during large-scale sequencing projects. DNA Seq. 1996;6:109–17.

Hall T. Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;4:95–8.

Barriel V. Molecular phylogenies and how to code insertion-deletion events. C R Acad Sci III. 1994;317:693–701.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–9.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–63.

Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–42.

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):772.

Vattier-Bernard G, Abonnenc E. Phlebotomus moucheti (Diptera Psychodidae), espéce nouvelle, eapturee dans les grottes au Cameroun et en Republique Centrafrieaine. Cahiers ORSTOM Ser Entomol Med Parasitol. 1967;05:67–70.

Lewis DJ, Kirk R. Notes on the Phlebotominae of the anglo-egyptian Sudan. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1954;48:33–45.

Vattier-Bernard G. Contribution a l’étude systématique et biologique des Phlébotomes cavernicoles en Afrique intertropicale. 1ère partie. Cahiers ORSTOM Ser Entomol Med Parasitol. 1970;8:175–230.

Vattier BG. Contribution à l’étude systématique et biologique des phlébotomes cavernicoles en Afrique intertropicale : 2ème partie. Cahiers ORSTOM Ser Entomol Medt Parasitol. 1970;8(3):231–88.

Vattier Bernard G, Adam J-P. Connaissances actuelles sur la répartition géographique des phlébotomes cavernicoles africains : considérations sur l’habitat et la biologie. Ann Spéléol. 1969;24(1):143–61.

Fisher-Reid MC, Wiens JJ. What are the consequences of combining nuclear and mitochondrial data for phylogenetic analysis? Lessons from Plethodon salamanders and 13 other vertebrate clades. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11(1):1–20.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the CIRMF (Gabon) and the IRD for the logistical support and funding of this project. We also deeply thank the Ranch de la Lékabi and the Parc de la Lékédi for their assistance during the field survey (Gabon). We also wish to thank Marc Ngangué for his field assistance and Heïdi Lançon for the English revision of the manuscript. Special thanks to Ray Gaab for assisting us during the fieldwork and discussions.

Funding

This research was funded by the CIRMF and the IRD.

Availability of data and material

Sequences for Sa. mirabilis are submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers: MIRA1: KU564275, KU555395, KT266679; MIRA2: KU564276, KU555396, KT266680; MIRA4: KU564277, KU555397, KT266681; MIK26: KU564278, KU555398, KT266682. Sequences for Sa. darlingi are submitted to the GenBank database under accessions numbers:

M20: KU564272, KU555392, KT266677; M21: KU564273, KU555393, KT266678; M60: KU564274, KU555394, KU555391.

Sequences for Sa. emilii are submitted to the GenBank database under accessions numbers: EMIL1: KU564279, KU555399, KT266675; EMIL2: KU564280, KU555400, KT266676. Sequences for Sa. moucheti are submitted to the GenBank database under accessions numbers: GAB27: KU564281, KU555401, KT266683; GAB65: KU564282, KU555402, KT266684; GAB71: KU564283, KU555403, KT266685; GAB84: KU564284, KU555404, KT266686.

Sequences for Se. schwetzi are submitted to the GenBank database under accessions numbers: Se.schwetzi: KU564286, KU555406, KU564287.

Voucher material (male of Spelaeomyia moucheti) is deposited in the IRD MIVEGEC collection in Montpellier, France.

Authors’ contributions

NR and JD motivated and designed the study. CP acquired funding for the field survey. NR, JO, BKM, AI and CP performed the fieldwork. NR and JD performed the identification of sand flies and all the morphological work. LHH and VL performed the molecular biology work and gene sequencing. JD drew the plates. NR, JD and LHH wrote the paper. All authors worked on the successive drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahola, N., Henni, L.H., Obame, J. et al. A molecular study of the genus Spelaeomyia (Diptera: Phlebotominae) with description of the male of Spelaeomyia moucheti . Parasites Vectors 9, 367 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1656-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1656-5