Abstract

Background

Studies of avian haemosporidians allow understanding how these parasites affect wild bird populations, and if their presence is related to factors such as habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, and climate change. Considering the importance of the highland Plateau of Mexico as part of the North American bird migratory route and as a region containing important habitat for numerous bird species, the purpose of this study was to document haemosporidian species richness and how habitat degradation, bird body condition, and distance from water sources correlate with bird parasitemia.

Methods

We assessed the presence of avian haemosporidians in three resident bird species through microscopy and PCR amplification of a fragment of the haemosporidian cytochrome b gene. Average parasitemia was estimated in each species, and its relationship with habitat degradation through grazing, bird body condition and distance from water bodies was assessed.

Results

High levels of parasitemia were recorded in two of the three bird species included in this study. Four lineages of haemosporidians were identified in the study area with nearly 50 % prevalence. Areas with highly degraded shrublands and villages showed higher parasitemia relative to areas with moderately degraded shrublands. No strong relationship between parasitemia and distance from water bodies was observed. There were no significant differences in prevalence and parasitemia between the two bird species infected with the parasites. Two of the sequences obtained from the fragments of the parasite’s cytochrome b gene represent a lineage that had not been previously reported.

Conclusions

Haemosporidian diversity in arid zones of the Mexican highland plateau is high. Shrubland habitat degradation associated to the establishment of small villages, as well as tree extraction and overgrazing in the surroundings of these villages, significantly enhances parasitemia of birds by haemosporidians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Haemosporidan parasites are transmitted by 17 genera of blood-sucking insects of the order Diptera [1, 2]. The study of these parasites allows the understanding of various aspects of avian ecology. Parasites indirectly reduce host fitness by decreasing their reproductive success and increasing breeding energy cost [3]. Therefore, parasitism by haemosporidians constitutes a selective force on bird populations. Consequently, interactions between birds and haemosporidian parasites have become a model of host-parasite relationships in ecology, conservation and vertebrate management [2, 4].

Around the world, presence of haemosporidians has been evaluated in tropical and temperate regions. Worldwide and within regions, prevalence values are highly variable, from 0 to 100 % depending on species, but in general, prevalence values tend to be slightly higher, around 50 to 80 %, in tropical regions [5–8], in comparison with temperate regions of North America and Europe where typical prevalence is around 50 and 70 %, respectively [9–12]. Diversity of haemosporidian lineages is also high throughout the globe but tend to be higher in continents than in islands, and in tropical than in temperate regions [13]. However, only a few haemosporidian parasite studies have focused on the diversity of these organisms in dry regions [3, 4, 14]. Knowledge related to factors influencing patterns of bird parasitism by haemosporidians in dry regions of the Americas is rather limited. One study in Arizona reported prevalence values from 0 to 80 %, and parasitemia by Haemoproteus related to nesting height, but no infections by Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon, and speculated that these results could be related to a number of factors including resistance to parasites, ecological barriers, or the absence of Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon vectors in this environment due to the limited water availability [4]. Furthermore, a study in arid zones of Venezuela reported 41 % haemosporidian prevalence and high species diversity including seven lineages from the genus Plasmodium and ten from Haemoproteus. It was also reported that humidity and temperature influence vector distribution and abundance [3].

There is also evidence that human-driven habitat changes and the increase in global temperatures are facilitating the expansion of parasite distribution ranges. Infection prevalence and parasite species richness respond to interactions between biotic and abiotic factors [3, 8, 15]. These processes create ecological niches that facilitate the establishment of vector populations [15]. Results of comparisons between anthropogenic and relatively undisturbed habitat types have suggested that habitat type and quality may influence the distribution and behavior of the vectors of these parasites, consequently affecting haemosporidian parasite dispersion patterns [15–17]. Others have reported that parasite dispersal may be influenced by habitat features such as proximity to water and climate change [18].

The establishment of villages, as well as tree extraction and overgrazing in the surroundings of these villages are common practices that have induced shrubland habitat degradation in a large proportion of the Mexican high plateau [19]. Therefore, we aimed at evaluating the effect of habitat degradation on parasitemia in resident bird species, and hypothesized that increasing levels of habitat degradation would be correlated with increasing parasitemia [19]. To further understand the underlying mechanisms associated with the effects of habitat degradation on parasitemia through potential negative effects on bird immune system, we assessed the potential correlation between individual bird body condition and parasitemia. Finally, because the construction of artificial ponds for the capture and storage of rainwater is a recurring practice in our study area and in most of the Mexican high plateau, we also evaluated the effect of proximity to water ponds on parasitemia. Our study reports the first records of haemosporidian parasites in avian populations from the highland plateau of Mexico and the effects of environmental variables on parasitemia. Thus, our results may function as the basis for future studies investigating host-parasite interactions between birds and haemosporidians in the region.

Methods

Study area

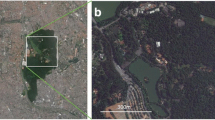

The study area is located between the municipalities of Charcas and Catorce, in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosi. Three communal-owned areas (ejidos) were included in the study: La Cardoncita (LC), Presa de Santa Gertrudis (PSG), and Guadalupe Victoria (GV) (UTM: E271793.37 N2610708.64, E278059.47 N2599525.12, E276057.75 N2582923.98 Zone 14 N). All study sites were embedded in a region known as “Zona Ixtlera” (Fig. 1), where trees of the genus Yucca have been historically extracted to obtain fiber, locally known as “Ixtle”, which is used for manufacture of ropes and other crafts. The vegetation in the area is characterized by the presence of rosette microphylous scrublands dominated by Yucca spp. in the tree layer, and Larrea tridentata and Flourensia cernua in the shrub layer [20]. A high diversity of species from the family Cactaceae is also present. The area contains gentle slopes and low mountains that facilitate storm water runoff to the lowlands. Annual rainfall averages 350 mm, and annual average temperature ranges from 10 to 20 °C [21, 22]. Altitude ranges from 2000 to 2300 m.

In the early 1930’s, a large portion of the expropriated land within the Mexican territory was given to local communities, and thus tenure in these lands was established in the “ejido” scheme. At this time, regional economies incentivized Yucca extraction for “Ixtle” production. Overgrazing was also established as an additional form of local economic subsistence. Because these economic activities continue to date, shrubland habitat degradation through the growth of villages, extraction of tree species, and overgrazing in their surrounding still prevail, thus creating a habitat gradient consisting of at least the following habitat types [19]: (i) “Isotal”, thereafter moderately degraded shrublands, where grazing and tree extraction is moderate; (ii) microphylous shrublands dominated by creosote bush in which the tree layer has been eliminated and intense goat grazing is ongoing, thereafter highly degraded shrublands; and (iii) villages where the natural vegetation has been almost completely removed and substituted by houses and unpaved roads. Three sampling sites representative of these levels of habitat degradation were established in each ejido. In each study site, bird communities were surveyed, and blood samples from birds were taken according to the methods described below.

Sampling

In the non-breeding (August to November) season of 2012, and during the reproductive (March to May) and non-breeding (September to November) seasons of 2013, birds were captured in each of the nine sampling sites. For this purpose, twenty 2.5 × 12 m ornithological mist nets were placed at random locations in each sampling site with the following restrictions: nets should be located at no less than 300 m from all habitat edges in order to avoid possible edge effects, all nets could be revised by one person in a period of 15 to 20 min, and no two nets would be located facing each other. This allowed us to revise nets quickly in order to avoid injuries to birds, and to maintain independence among nets. From each individual of Haemorhous mexicanus (house finch), Melozone fusca (canyon towhee), and Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus (cactus wren) a blood sample of approximately 200 μl was taken by jugular vein puncture [23]. Blood samples were stored in eppendorf tubes with 1 ml of Longmire buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaCl, 0.5 % SDS) which allows storage of blood samples at room temperature without compromising DNA integrity [24]. Additionally, wing cord and body mass of all captured individuals were measured following the procedures recommended by Ralph et al. [25].

Microscopy and blood smears

Blood smears were prepared following standard techniques for haemosporidian studies [1]. Slides were examined using an optical Motic BA400 microscope with a 100× objective amplification. Parasitemia was quantified for each smear based on 100 random fields, approximately 150 erythrocytes/field = 15,000 total erythrocytes, in which the number of infected cells was recorded. Parasite identification procedures followed the characteristics described by Valkiūnas [1], specifically examining the state of development of micro and macro-gametocytes, meronts, and the presence of pigment granules.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from each blood sample using the DNeasy blood & tissue isolation kit (Qiagen, Venlo Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To verify DNA integrity, extractions were screened on 1 % agarose gels and the quality and quantity of the extracted DNA was assessed with a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Molecular diagnosis by PCR

Presence or absence of haemosporidian parasites was determined in each sample through amplification of fragments of approximately 480 bp of the parasite cytochrome-b gene using HaemF (5'-ATG GTG CTT TCG ATA TAT GCA TG-3') and HaemR2 (5'-GCA TTA TCT GGA TGT GAT AAT GGT-3') primers [26]. 25 μl PCR reactions were carried out; each reaction contained 20–50 ng of total DNA, 1× PCR buffer II (100 mM Tris–HCl, pH8.3, 500 mM KCl), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.125 mM each dNTP, 0.6 μM of each primer and 0.6 U of AmpliTaq (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). The reactions were conducted according to the protocol developed by Bensch et al. [26] as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 45 s, and final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. All reactions were carried out in a 2720 (ABI, Foster, CA) or MJMini (BioRad, Hercules, California thermocycler) thermal cyclers. PCR products were examined by 1 % agarose gel electrophoresis and the ones with the expected size were purified for sequencing. Haemosporidian parasite prevalence was estimated using the R package “Prevalence” [27] that uses a sensitivity, the probability that a truly infected individual reacts positively, and specificity, the probability that an individual truly uninfected yields negative results, diagnostic test. This test corrects the bias due to possible false positives and false negatives [28], obtaining an unbiased estimate of the real prevalence of infection through Bayesian inference using the following equation:

where: π is the true prevalence, P is the apparent prevalence, D is the status of infection, TP is true positive, FN is false negative, FP is false positive, and TN is true negative.

Sequence analysis

Sequencing was performed on a 3130 Genetic Analyzer sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) in the National Laboratory of Agricultural, Medical, and Environmental Biotechnology (LANBAMA-IPICYT). The sequences obtained were compared with sequences deposited in public databases such as NCBI and MalAvi [29] to identify the species or genera of organisms causing infection in the samples. All sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (Accession numbers KR818942-KR819003) (for details see Additional file 1). Following the criteria published by Durrant et al. [9], sequences that diverged by two or more nucleotides were considered as different lineages, and to corroborate these as new lineages, we submitted our sequences to the MalAvi database. (GenBank accession numbers KR819002 and KR819003 for CatoC00400_MELFUS01 and CatoC00443_MELFUS01, respectively). Similarity between the obtained and the previously known sequences were determined through a Neighbor Joining (NJ) analysis. Evolutionary distances between sequences were calculated using the three-parameter model of Tamura, specifying the distribution of rate variation among sites γ = 0.263. To construct the cladogram, 1000 replicates were used in a bootstrap test to calculate the percentage of association between taxa. All these analyses were conducted in MEGA version 6 [30]. Because in our sequence analysis we could not detect co-infections, we complemented this analysis with microscopy techniques.

Hydrological analysis

Through visual interpretation of satellite imagery from Google Earth of the study area, all permanent and temporary water bodies present in the study area were located and geo-referenced. Water bodies in our study region are characterized by showing a smooth texture and being bright in aerial imagery. Using QGIS 2.0.1 Dufour software [31], these water bodies were digitized to calculate the total area covered by water. We also used the Dufour QGIS 2.0.1 software [31] and Google Earth imagery to measure distances between each sampling site and the nearest water body.

Statistical analysis

Differences in prevalence among bird species were assessed with a Chi-square test. Parasitemia was compared between bird species using a t test for independent samples specifying the negative binomial distribution for these count data. These tests were only applied to the two species yielding positive parasitemia.

For each bird species, we fitted a series of Generalized Linear Models (GLM’s) to assess the effects of factors influencing parasitemia including habitat degradation [19], distance from nearest water body, and bird body condition. Body condition was determined for each individual bird according to the Peig and Green escalated mass ratio [32], which is based on the relationship between body weight and a linear measure of length (e.g. wing length) of each individual. This has recently proved to be a more reliable indicator of true organismal condition than the most popular index based on the residuals of the ordinary least squares regression of body mass vs any measure of body size. The number of parasitized cells was used as the dependent variable. Because evidence of over dispersion was found, the negative binomial distribution was used for these count data.

We used Akaike’s Information Criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc), and Akaike weights (w i ) to evaluate support for several a priori generalized linear models of our hypotheses related to effects influencing parasitemia [33]. Our set of a priori models explaining parasitemia for the house finch included: 1) a null model with no explanatory variables, 2, 3, and 4) models of habitat degradation, distance from water bodies, and body condition index as the only explanatory variables, 5) a multiplicative model including habitat degradation, bird body condition, and the interaction of these two variables, and 6) a multiplicative model including distance from nearest water body, bird body condition, and the interaction of these two variables. For the canyon towhee we did not consider a model containing bird body condition as the only explanatory variable because the algorithm failed to converge, presumably due to the relatively small sample size. We did not include a multiplicative model containing habitat degradation and distance from water bodies for any of the studied species because results of an exploratory analysis indicated that there was autocorrelation between these two explanatory variables (one way ANOVA, P < 0.01), presumably because distance from water bodies tends to increase with increasing distance from villages. Therefore, distance from water bodies is smallest at villages, intermediate at highly degraded shrublands, and highest at moderately degraded shrublands. It is recommended that whenever two explanatory variables are autocorrelated, one of these variables should be dropped from the model [34]. The null model was used to determine if a random model with no explanatory variables generated a better model than inclusion of any of the remaining variables. We used AICc, Akaike differences (ΔAICc), and w i [33] to rank models from most to least supported by the data. Then, to account for model-selection uncertainty, we calculated model-averaged weighted parameter estimates and their associated standard errors using w i as weights as suggested by Burnham & Anderson [33]. Because some variables were more represented in our set of candidate models than others, we rescaled the w i values following recommendations of Burnham & Anderson [33] to avoid possible model redundancy. Finally, we used weighted parameter estimates and weighted standard errors to construct graphs depicting the response in parasitemia to the variables that were present in the best-supported model and those receiving equivalent support from the data as the best-supported model (ΔAICc ≤ 2). All generalized linear models and chi square tests were conducted using R and the MASS library [35]. Because w i values were rescaled, we obtained log likelihood values from R, and used these values to calculate AIC tables and average weighted parameter estimates in a spreadsheet adhering to the formulas published in Burnham & Anderson [33].

Results

Diagnostic tests

Microscopy analysis revealed the presence of haemosporidian parasites in samples of two bird species, house finches and canyon towhees, whereas in cactus wren samples, only normal erythrocytes were observed. As is typical of the life-cycle of Haemoproteus spp., the asexual stages of these parasites, microgametocytes and macrogametocytes, within erythrocytes from infected birds were observed in most of our samples (Fig. 2). On the other hand, no meronts of Plasmodium were detected in red blood cells, but the presence of Plasmodium was evidenced by PCR amplification in two birds. Haemosporidian prevalence was 47.5 % for the canyon towhee, and 44.3 % for the house finch (Table 1).

In general, molecular diagnosis results matched those obtained from microscopy. However, the PCR amplification yielded six false negatives, four of which might be related to low concentration of parasite DNA that was corroborated through microscopy which yielded < 16 parasitized erythrocytes. Two other false negatives yielding somewhat less moderate parasitemia, consisting of 161 and 280 infected erythrocytes, respectively, were found and might be related to contamination or presence of inhibitors in the PCR reactions in spite of the fact that analyses were conducted using three replicates. Additionally, PCR amplification and sequencing of the DNA fragments of the parasites did not show cases of co-infection, but these were detected with microscopy examination in one of the house finch samples which revealed two cells infected with Plasmodium and eleven with Haemoproteus. The estimated prevalence of infection did not differ between the two species with positive cases (χ 2 = 0.001, df = 1, P = 0.974). The house finch had the highest parasitemia, but this value did not differ significantly between the two species (t = -1.375, df = 141, P = 0.171, Fig. 3).

Parasitemia (number of parasites/100 fields). Parasites were recorded in blood smears of the house finch and the canyon towhee from the “Ixtlera” region in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Black dots correspond to individuals yielding > 100 cells infected by haemosporidian parasites. t = 1.915, df = 55.408, P = 0.0606

Sequence analysis

The amplicon sequencing revealed that in the study area house finches and canyon towhees get infected by at least three different lineages of the genus Haemoproteus. One lineage of the genus Plasmodium was detected in only one sample of each bird species, whilst two sequences from canyon towhee samples differ in eight nucleotides from the reference sequences. According to the method for delimiting lineages published by Bensch et al. [26, 29] these sequences represent a lineage that has not been previously reported. This was indeed corroborated as a new lineage by MalAvi (mbio-serv2.mbioekol.lu.se/Malavi/). The new lineage was designated as MELFUS01. Therefore the sequences belonging to this lineage are in a separate clade based on the similarity between sequences (Fig. 4).

Specific and intraspecific diversity of haemosporidian parasites detected at the “Ixtlera” region. NJ cladogram showing specific and intraspecific diversity of haemosporidian parasite sequences obtained from samples yielding positive results from the house finch and canyon towhee from the “Ixtlera” region of San Luis Potosi. The sequences show similarity to the genus Plasmodium and subgenera Haemoproteus and Parahaemoproteus. CatoC00400 and CatoC00443 (in bold) correspond to a new lineage (MELFUS01). Only representative sequences are shown, for a full list of samples see Additional file 1. Bootstrap values are shown next to nodes. Underlined names correspond to reference sequences published on Genbank (see Additional file 1)

Effect of environmental variables

Through the hydrological analysis, we identified a total of 54 ponds with an average area of 1.2 ± 1.5 ha. Surface covered by water when all ponds are full is approximately 55 ha. Mean distance from water bodies was 1.51 km (standard error, SE = 0.13) for moderately degraded shrublands, 0.51 km (SE = 0.12) for highly degraded shrublands, and 0.24 km (SE = 0.04) for villages.

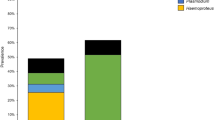

Though the null model was the one receiving the best support from the data for the house finch, the model containing multiplicative effects of body condition and habitat quality, and the model containing body condition index as the only explanatory variable received equivalent support from the data as the best supported model (ΔAICc < 2, Table 2). Based on these models, and on model-averaged parameter estimates (Table 3), parasitemia was highest in highly degraded shrublands, and lower in villages and in moderately degraded shrublands (Fig. 5a). In addition, parasitemia increased with increasing body condition, but the rate of this increase was almost negligible and standard errors were large (Fig. 5b).

Effects of different factors on parasitemia in house finches. Effect of (a) habitat quality and (b) body condition on parasitemia (number of parasites/100 fields) in house finches from shrubland sites at the “Ixtlera” region of northern San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Error bars and dotted lines indicate ± one standard error around the mean

For the canyon towhee, the model containing habitat quality as the only explanatory variable was the one receiving the best support from the data. Three additional models receiving equivalent support from the data (ΔAICc < 2, Table 4) included the model containing proximity to ponds, the model containing multiplicative effects of habitat quality and bird body condition, and the model containing multiplicative effects of proximity to water bodies and body condition index. Based on the best supported models, and on model-averaged parameter estimates (Table 5), parasitemia for this species was highest in villages and highly degraded shrublands, and low at moderately degraded shrublands (Fig. 6a). Parasitemia increased with distance from water (although standard errors were quite large, Fig. 6b), and with increasing body condition index. This last increase, however, was very slight and standard errors were quite large (Fig. 6c).

Effects of different factors on parasitemia in canyon towhees. Effect of (a) habitat quality, (b) distance from water bodies, and (c) body condition on parasitemia (number of parasites/100 fields) in canyon towhees from shrubland sites at the “Ixtlera” region of northern San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Error bars and dotted lines indicate ± one standard error around the mean

Discussion

The haemosporidian parasite prevalence that we recorded in two resident bird species of the highland plateau of San Luis Potosi are comparable to those previously reported in arid zones [3, 4, 14]. On the other hand, the prevalence values encountered are lower in comparison to those reported by other studies from tropical [5–8] and temperate [10–12] regions. Within individual sites, prevalence varies greatly among bird species. Therefore, future studies considering more bird species from dry areas will provide additional knowledge about within-region variation in prevalence values. In comparison to our results, Deviche et al. [4] failed at registering the genus Plasmodium in bird blood samples from arid Arizona habitats. At present it is difficult to understand the reasons for this difference; though water availability, which is sometimes necessary for the establishment of vector populations, may be a factor into play. Other factors such as exposure to parasites brought by migrants, resistance to parasites, ecological barriers, and other idiosyncrasies of both parasites and vectors may be important, and it is currently impossible to obtain more specific conclusions without further investigations simultaneously considering host and vector distribution and ecology within our study region. Notwithstanding, some literature indicates that Plasmodium prevalence is in general substantially smaller than that of Haemoproteus [36, 37], which is consistent with the lowest prevalence that we found for this genus and with the reports of Deviche et al. [4].

Haemosporidian infection prevalence is variable among bird species and even absent in some [1]. Lack of infection in the cactus wren may be related to one or many extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Potential extrinsic factors include absence of the specific host-parasite assemblage [38], which owes to evolutionary causes, and potential competitive exclusion of vectors by ectoparasites [39]. As reported for other species [4], behavior and some adaptations may be among intrinsic factors influencing our observations. Although the cactus wren tolerates some disturbance, it tends to settle far from human settlements, where vectors may be absent [38]. In addition, it is not highly dependent on sites with available water [40] as it seeks microhabitats with moderate temperatures and its activity decreases to prevent heat stress as the temperature reaches critical levels. Moreover, its physiological adaptations allow it to get water from food to maintain water balance even in extreme temperature conditions [41]. In addition, although cactus wren nesting is not well studied, it may be that it has nest defense strategies as the one reported for Parus caeruleus which uses herb species as a repellent against Culex mosquitoes to protect their nest [42]. Immune capacity may also benefit some species [43] and this could be the case of the cactus wren. Microbicidal capacity, for instance, which may be associated to nutrition quality and age [44, 45], could be a factor into play in our study as all captured cactus wren individuals were adults with no weight, size, or length below normal values for the species. In addition, as has been reported by Girard et al. [46] for other species, previous infection by other pathogens may have stimulated antibody production, which in turn may improve immune response to other infections. Although these could be important factors in a possible resistance of this species to infection by haemosporidians, these hypotheses should be experimentally tested. Such studies should include physiological tests in this species in order to understand its adaptation against such parasites, if any.

Because bird migration has contributed significantly to promoting the establishment of widespread haemosporidian parasite distributions throughout most of the planet [1], future studies should investigate haemosporidian parasites in blood samples from migratory birds using the area, and possible transmission between migratory and resident species, perhaps by banding birds, and simultaneously analyzing samples from residents, migrants, and the vector community. In such study, nestlings and juveniles from resident species that had fledged in our study sites during the times in which migrants were absent, could provide very valuable information. If migrants participate significantly in the parasite transmission process, prevalence in these juveniles would be expected to be significantly lower during the time in which migrants are absent. But caution must be taken in such a study because once a lineage is introduced by migrants, resident birds may function as reservoirs.

This study recorded a statistical relation between habitat quality and parasitemia of infected birds. This result might be related to different factors associated to habitat quality such as food availability. Damage to the immune system of birds inhabiting moderately degraded shrublands may also play a role in parasitemia. It has been previously documented that the same acute stress response that allows organisms to survive short-term environmental stressors, such as unusual weather events or the presence of a predator, via the release of corticosterone in birds, may lead to suppression of the immune system and the consequent increase in susceptibility to disease when the source of stress is prolonged, such as under anthropogenic disturbances [47]. Therefore, the higher parasitemia documented here at highly degraded shrublands could be the result of depressed immune system in these habitats. The correlation found between body condition and parasitemia provides additional evidence for the hypothesis that habitat degradation may influence the immune system, which in turn may promote higher parasitemia in house finches and canyon towhees inhabiting degraded habitats. This type of mechanism has been previously reported for other vertebrates [15, 16, 48]. Future studies investigating factors such as status of the immune system, food availability, vector densities in relation to different habitat features, as well as manipulative experiments could help disentangle these factors. Moreover, our results should be viewed with caution because parasitemia may be more related to the stage of infection in which each individual bird is recorded than to environmental factors.

The richness of parasite lineages found in this study is similar to that reported in other arid areas [3, 4]. The presence of different species depends on their environmental needs. Species of the genus Leucocytozoon, for instance, require the existence of well-oxygenated water flows for the successful development of the larval phase of at least some of their vectors such as Similillium spp. which are blood-sucking flies of the family Simulidae [49]. This is probably why this genus is uncommon in arid environments. According to our molecular diagnosis, four different lineages of the genera Plasmodium and Haemoproteus are present in our study area. These lineages have wide distributions; Haemoproteus sp. PYERY01 has been reported at many locations in the entire planet, except for Asia and the Antarctica [29, 50]. On the other hand, Parahaemoproteus sp. ICTLEU01 has been registered only at the American continent, specifically in North America, and at the Galapagos [51, 52]. Similarly, Plasmodium sp. MOLATE01 has been reported only at some places in the USA infecting brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater) and house finches [53, 54]. We found this lineage infecting a new host, the canyon towhee. Haemoproteus sp. SISKIN1 is the most widespread lineage we found. It has been recorded in Lithuania, New York, California, Alaska, Russia and the Czech Republic, in a variety of hosts including Carduelis spinus, Loxia curvirostra, Haemorhous mexicanus, Passer domesticus, Carpodacus erythrinus and Carduelis pinus [54, 55]. Since all these lineages are widely distributed, future investigations should aim at determining the role that both resident and migrant species play in the infectious process in this region.

The similarity analysis showed that two of the sequences obtained had a difference of eight nucleotides compared to the sequence of the closest lineage (Parahaemoproteus ICTLEU01), and more differences regarding Plasmodium and Haemoproteus lineages. According to Bensch et al. lineage delimitation criteria [26, 29], this result suggests the presence of a lineage that has not been previously reported. Therefore, our results contribute to the knowledge of intraspecific diversity of these parasites.

Conclusion

Haemosporidian parasite diversity in the highland plateau of San Luis Potosi includes at least four lineages from two genera, plus two sequences from a lineage that has not been reported previously. Parasitemia varies tremendously between individual species. While some suffer from high parasitemia, for unknown causes, others seem not to be parasitized. According to our results, habitat degradation by the establishment of small villages, and the associated tree extraction and overgrazing in the immediacies of these villages seems to increase parasitemia. Consequently, management practices for the mitigation of these negative effects near the villages such as maintenance of native trees and shrubs within villages, reforestation practices with native trees and shrubs in highly degraded shrublands, and the control of browse by domestic animal species could probably help in controlling parasitemia.

References

Valkiūnas G. Avian malaria parasites and other Haemosporidia. CRC Press; 2005.

Braga ÉM, Silveira P, Belo NO, Valkiũnas G. Recent advances in the study of avian malaria: An overview with an emphasis on the distribution of Plasmodium spp. in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106:3–11.

Belo NO, Rodríguez-Ferraro A, Braga EM, Ricklefs RE. Diversity of avian haemosporidians in arid zones of northern Venezuela. Parasitology. 2012;139:1021–8.

Deviche P, McGraw K, Greiner EC. Interspecific differences in hematozoan infection in Sonoran desert Aimophila sparrows. J Wildl Dis. 2005;41:532–41.

Lutz HL, Hochachka WM, Engel JI, Bell JA, Tkach VV, Bates JM, et al. Parasite prevalence corresponds to host life history in a diverse assemblage of afrotropical birds and haemosporidian parasites. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0121254.

Loiseau C, Iezhova T, Valkiūnas G, Chasar A, Hutchinson A, Buermann W, et al. Spatial variation of haemosporidian parasite infection in African rainforest bird species. J Parasitol. 2010;96:21–9.

Sehgal RNM, Buermann W, Harrigan RJ, Bonneaud C, Loiseau C, Chasar A, et al. Spatially explicit predictions of blood parasites in a widely distributed African rainforest bird. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;278:1025–33.

Lacorte GA, Flix GMF, Pinheiro RRB, Chaves AV, Almeida-Neto G, Neves FS, et al. Exploring the diversity and distribution of neotropical avian malaria parasites - a molecular survey from southeast brazil. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57770.

Durrant KL, Beadell JONS, Ishtiaq F, Graves GR, Olson SL, Gering E, et al. Avian hematozoa in South America: a comparison of temperate and tropical zones. Ornithol Monogr. 2006;60:98–111.

Van Rooyen J, Lalubin F, Glaizot O, Christe P. Altitudinal variation in haemosporidian parasite distribution in great tit populations. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:139.

Ricklefs RE, Swanson BL, Fallon SM, Martínez-Abraín A, Scheuerlein A, Gray J, et al. Community relationships of avian malaria parasites in southern Missouri. Ecol Monogr. 2005;75:543–59.

Palinauskas V, Markovets MY, Kosarev VV, Efremov VD, Sokolov LV, Valkiūnas G. Occurrence of avian haematozoa in Ekaterinburg and Irkutsk districts of Russia. Ekologija. 2005;4:8–12.

Clark NJ, Clegg SM, Lima MR. A review of global diversity in avian haemosporidians (Plasmodium and Haemoproteus: Haemosporida): New insights from molecular data. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44:329–38.

Bobby Fokidis H, Greiner EC, Deviche P. Interspecific variation in avian blood parasites and haematology associated with urbanization in a desert habitat. J Avian Biol. 2008;39:300–10.

Belo NO, Pinheiro RT, Reis ES, Ricklefs RE, Braga ÉM. Prevalence and lineage diversity of avian haemosporidians from three distinct cerrado habitats in Brazil. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17654.

Patz JA, Graczyk TK, Geller N, Vittor AY. Effects of environmental change on emerging parasitic diseases. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30(12):1395–405.

Vittor AY, Gilman RH, Tielsch J, Glass G, Shields T, Lozano WS, et al. The effect of deforestation on the human-biting rate of Anopheles darlingi, the primary vector of falciparum malaria in the Peruvian Amazon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:3–11.

Lapointe DA, Atkinson CT, Samuel MD. Ecology and conservation biology of avian malaria. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1249:211–26.

Garza-Hurtado R-F. Respuesta de la avifauna a los cambios en la estructura vegetal en un gradiente de degradación del altiplano potosino. 2011. Instituto Potosino de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica A.C.

Rzedowski J. Vegetación del estado de San Luis Potosí. Acta Cient Potosina. 1966;5:1–291.

INEGI. Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. San Luis Potosí, Mexico: INEGI; 2009.

INEGI. Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Charcas, San Luis Potosí, Mexico: INEGI; 2009.

Canales-Delgadillo JC, Scott-Morales L, Korb J. The influence of habitat fragmentation on genetic diversity of a rare bird species that commonly faces environmental fluctuations. J Avian Biol. 2012;43:168–76.

Longmire JL, Lewis AK, Brown NC, Buckingham JM, Clark LM, Jones MD, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of a highly polymorphic centromeric tandem repeat in the family Falconidae. Genomics. 1988;2:14–24.

Ralph CJ, Geupel GR, Pyle P, Martin TE, DeSante DF. Handbook of field methods for monitoring landbirds. USDA Forest Serv/UNL Fac Publ. 1993;144:1–41.

Bensch S, Stjernman M, Hasselquist D, Ostman O, Hansson B, Westerdahl H, et al. Host specificity in avian blood parasites: a study of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus mitochondrial DNA amplified from birds. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:1583–9.

Devleesschauwer B, Torgerson P, Charlier J, Levecke B, Praet N, Dorny P, Berkvens D SN. Prevalence: Tools for prevalence assessment studies. 2013. Available at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/prevalence/index.html.

Speybroeck N, Devleesschauwer B, Joseph LBD. Misclassification errors in prevalence estimation: Bayesian handling with care. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:791–05.

Bensch S, Hellgren O, Pérez-Tris J. MalAvi: A public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9:1353–8.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9.

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Found. Proj. 2015. Available at http://www.qgis.org/es/site/.

Peig J, Green AJ. New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: the scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos. 2009;118:1883–91.

Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2002.

Neter J, Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Li W. Applied linear statistical models. Chicago: Trwin/McGraw-Hill; 1996.

R Development Core Team. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

Beadell JS, Gering E, Austin J, Dumbacher JP, Peirce MA, Pratt TK, et al. Prevalence and differential host-specificity of two avian blood parasite genera in the Australo-Papuan region. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:3829–44.

Scheuerlein A, Ricklefs RE. Prevalence of blood parasites in European passeriform birds. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271:1363–70.

Bennett GF, Bishop MA, Peirce MA. Checklist of the avian species of Plasmodium Marchiafava & Celli, 1985 (Apicomplexa) and their distribution by avian family and Wallcean life zones. Syst Parasitol. 1993;26:171–9.

Martínez-Abraín A, Esparza B, Oro D. Lack of blood parasites in bird species: does absence of blood parasite vectors explain it all? Ardeola. 2004;51(1):225–32.

Yohannes E, Križanauskiené A, Valcu M, Bensch S, Kempenaers B. Prevalence of malaria and related haemosporidian parasites in two shorebird species with different winter habitat distribution. J Ornithol. 2009;150:287–91.

Ricklefs RE, Hainsworth RF. Temperature dependent behavior of the cactus wren. Ecology. 1968;49:227–33.

Lafuma L, Lambrechts MM, Raymond M. Aromatic plants in bird nests as a protection against blood-sucking flying insects? Behav Processes. 2001;56:113–20.

Ricklefs RE. Embryonic development period and the prevalence of avian blood parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4722–5.

Smith VH, Jones TP, Smith MS. Host nutrition and infectious disease: an ecological view. Front Ecol Environ. 2005;3(5):268–74.

Irene Tieleman B, Williams JB, Ricklefs RE, Klasing KC. Constitutive innate immunity is a component of the pace-of-life syndrome in tropical birds. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272:1715–20.

Girard J, Goldberg TL, Hamer GL. Field investigation of innate immunity in passerine birds in suburban Chicago, Illinois, USA. J Wildl Dis. 2011;47:603–11.

Ellis RD, McWhorter TJ, Maron M. Integrating landscape ecology and conservation physiology. Landsc Ecol. 2012;27(1):1–12.

van der Hoek W, Konradsen F, Amerasinghe PH, Perera D, Piyaratne MK, Amerasinghe FP. Towards a risk map of malaria for Sri Lanka: the importance of house location relative to vector breeding sites. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:280–5.

Butler JF, Hogsette JA. Black flies, Simulium spp. (Insecta: Diptera: Simuliidae). Lincoln, NE: Publications from USDA-ARS/UNL faculty; Paper 995. 1998.

Marzal A, García-Longoria L, Cárdenas Callirgos JM, Sehgal RN. Invasive avian malaria as an emerging parasitic disease in native birds of Peru. Biol Invasions. 2014;17(1):39–45.

Outlaw DC, Ricklefs RE. On the phylogenetic relationships of haemosporidian parasites from raptorial birds (Falconiformes and Strigiformes). J Parasitol. 2009;95:1171–6.

Levin II, Zwiers P, Deem SL, Geest EA, Higashiguchi JM, Iezhova TA, et al. Multiple lineages of avian malaria parasites (Plasmodium) in the Galapagos Islands and evidence for arrival via migratory birds. Conserv Biol. 2013;27:1366–77.

Beadell JS, Ishtiaq F, Covas R, Melo M, Warren BH, Atkinson CT, et al. Global phylogeographic limits of Hawaii’s avian malaria. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2006;273:2935–44.

Kimura M, Dhondt AA, Irby JL. Phylogeographic structuring of Plasmodium lineages across the North American range of the house finch (Carpodacus mexicanus). J Parasitol. 2006;92:1043–9.

Oakgrove KS, Harrigan RJ, Loiseau C, Guers S, Seppi B, Sehgal RNM. Distribution, diversity and drivers of blood-borne parasite co-infections in Alaskan bird populations. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44:717–27.

Acknowledgement

This work is part of a Research Project funded by the Basic Science CONACYT program (project number CB-2012-1-183377). MTR-P thanks CONACYT for the scholarship awarded for the completion of this study and financial support by FORDECYT/193512/2012. We thank Dr. Gerardo Argüello-Astorga who provided us space and material support for the project’s execution, as well as helpful suggestions, and G. Valkiūnas who granted us access to a lab in the Nature Research Center, Vilnius, Lithuania and provided help interpreting parasite images. All authors thank Carlos Armando, Jachar Arreola and Karina Monzalvo who helped in the field work. The collection of samples was made using a permit granted by SEMARNAT with number FAUT −0157.

Authors’ contributions

JCC-D, LCV, MTR-P, and LRR, conceived the study, MTR-P, JCC-D and LCV collected samples; MTR-P and JCC-D processed samples and generated molecular and sequencing data; MTR-P, LRR and JCC-D aligned and analyzed the sequences; MTR-P and JCC-D processed and analyzed blood smears; MTR-P and JCC-D analyzed the results, MTR-P and JCC-D prepared the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics statement

All fieldwork was conducted using a bird capture permit issued by SEMARNAT, the Secretariat for Environmental Management and Natural Resources of Mexico (Permit number FAUT-0157). We complied with all Mexican and international regulations required for conducting wildlife research in the field including those from IUCN and CITES. No individuals were harmed during data collection, and all individuals were released on the capture location after samples and measurements were taken.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

GenBank accession numbers. Sequences 1 to 10 correspond to reference sequences in the NJ cladogram, 11 to 27 correspond to sequences obtained from samples of the canyon towhee (M. fusca) and 28 to 72 are sequences obtained from samples of the house finch (H. mexicanus). Sequences in bold are shown in the NJ cladogram. (CSV 4 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Reinoso-Pérez, M.T., Canales-Delgadillo, J.C., Chapa-Vargas, L. et al. Haemosporidian parasite prevalence, parasitemia, and diversity in three resident bird species at a shrubland dominated landscape of the Mexican highland plateau. Parasites Vectors 9, 307 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1569-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1569-3