Abstract

Background

Ivermectin is used extensively globally for treatment of helminthic and ectoparasitic infections in animals and humans. The effect of excreted ivermectin on non-target organisms in aquatic and terrestrial environments has been increasingly reported. Due to its low water solubility and adsorption to sediments, the ivermectin exposure-risk to aquatic organisms dwelling in different strata of water bodies varies. This study assessed the survival of larvae of Anopheles gambiae Giles and Culex quinquefasciatus Say, when exposed to low concentrations of ivermectin under laboratory conditions.

Methods

A total of 1800 laboratory reared mosquito larvae of each species were used in the bioassays. Twelve replicates were performed, each testing 6 concentrations of ivermectin (0.0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0 and 10.0 parts per million (ppm)) against third instar larvae of An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus. Larval mortality was recorded at 24 and 48 h post addition of ivermectin.

Results

Survival declined markedly with increase in ivermectin concentration in both species. While mean survival of An. gambiae at 24 h of exposure was 99.6 %, 99.2 % and 61.6 % in 0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 ppm of ivermectin, respectively, the mean survival of Cx. quinquefasciatus at the same dosage and time was 89.2 %, 47.2 % and 0.0 %. A similar pattern, but with higher mortality, was observed after 48 h of exposure. Comparison between the species revealed that Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae were significantly more affected by ivermectin than those of An. gambiae, both at 24 and 48 h.

Conclusions

Low concentrations of ivermectin in the aquatic environment reduced the survival of larvae of An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus, with the effect being more marked in the latter species. It is suggested that this difference may be due to the different water strata occupied by the two species, with ivermectin adsorbed in food that sediment being more readily available to the bottom feeding Cx. quinquefasciatus than the surface feeding An. gambiae larvae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Ivermectin is an important drug for treatment of many helminthic and ectoparasitic infections in animals and humans globally [1]. It has been extensively used in the veterinary field, and its use in humans has recently been scaled up in large programmes to control lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis in endemic areas particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [2, 3]. Due to its effectiveness in treating these infections, many of which are particularly common in the tropics, it has been referred to as a ‘wonder drug’ [4]. However, in addition to the anti-parasitic potentials, ivermectin has a broad spectrum of activity against a wide range of other invertebrates, and its effect in the environment on non-target aquatic and terrestrial organisms has been increasingly documented [5].

In relation to its broad spectrum of activity, the ongoing Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis has reported promising beyond-programme benefits of ivermectin mass drug administration (MDA), including simultaneous curative effects on intestinal and skin parasitic infections [3]. Entomological field studies in the programme areas have moreover documented a decline in survival of female Anopheles gambiae that feed on humans shortly after mass treatment with ivermectin [6–8]. Laboratory studies have confirmed this effect of ivermectin on adult anopheline vector survival, and have also demonstrated a reduced fecundity of these vectors following a blood meal from ivermectin treated humans or cattle [9, 10]. Due to this effect on important malaria vectors in sub-Saharan Africa, ivermectin has been considered as a potential tool for future malaria control [11, 12].

Other studies have demonstrated that non-target organisms in terrestrial environments can be affected by faecal excreta from ivermectin-treated animals, while in aquatic environments they can be affected both directly from excreta dropped in water or indirectly through runoff of ivermectin contaminants [13, 14]. Extensive literature on the effect of ivermectin on non-target organisms living in terrestrial and aquatic environments has been summarized previously [5]. Ivermectin has low water solubility and partitions rapidly in aquatic environments from the water phase to sediment particles [15–17]. Its low water solubility and rapid adsorption to sediments suggest that ivermectin may pose a variable risk of exposure to aquatic organisms living or feeding in different strata of the water body.

In sub-Saharan Africa, An. gambiae is the most important vector of malaria, and this species, as well as Culex quinquefasciatus, are important vectors of lymphatic filariasis. It is possible that the widespread use of MDA with ivermectin could have affected transmission of these infections through an effect on the mosquito vector larvae, and perhaps even could have contributed to the marked change in composition of the vector mosquitoes observed in recent years in north eastern Tanzania [18, 19]. In their aquatic habitat anopheline and culicine larvae feed preferentially in different strata of water but both come to the surface for breathing. While anopheline larvae are mainly surface feeders, culicine larvae feed in the sediment at the bottom of water strata [20]. This feeding behavior may most likely lead to differential ivermectin exposure-risks between the two mosquito species if they reside in ivermectin contaminated habitats. Studies have shown that different species of mosquito larvae are susceptible to low concentrations of ivermectin in laboratory settings as well as in natural mosquito breeding habitats [21, 22]. On this background, the present study assessed and compared the survival of An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito larvae when exposed to low concentrations of ivermectin under laboratory conditions.

Methods

Mosquito larvae

Larvae of An. gambiae sensu stricto (a colony originating from Kisumu, Kenya) and Culex quinquefasciatus (a colony originating from Arusha, Tanzania) mosquitoes were used for the laboratory bioassays. Both colonies had been maintained for several generations at the insectary of the National Institute for Medical Research, Amani Research Centre, Tanga, Tanzania, and were previously also used in a study on the effect of human ivermectin treatment on blood feeding adult mosquitoes [10]. They were maintained using recommended standard mosquito rearing techniques [23]. Larvae of An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus were fed with Nutrafin® fish food (Hagen, Taiwan) and Whiskas® cat food (Mars Africa, South Africa), respectively before and during bioassays. Although both foods initially float on the surface of the water, the cat food sinks to the bottom relatively quickly compared to the fish food.

Preparation of ivermectin solutions

An ivermectin stock solution was first prepared by dissolving 200 mg powdered ivermectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) in 20 ml dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (Hybri-Max®, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The resultant 1.0 % (10 mg/ml) stock solution was kept frozen in 2 ml aliquots until use. On the experimental day, one aliquot of stock solution was thawed and serially diluted in distilled water as previously recommended [24]. In brief, a ten-fold dilution series was prepared by first transferring 2 ml of stock solution to 18 ml of distilled water to make a 0.1 % concentration, and by subsequently repeating this procedure by transferring 2 ml of the latest solution to 18 ml of distilled water to make 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 and 0.00001 % concentrations of ivermectin. Control solutions (with no ivermectin) comprised of 2 ml DMSO in 18 ml distilled water.

Larval bioassays

Bioassays with An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae were run simultaneously (in parallel). For each species twelve replicates were performed, with four replicates starting on three separate dates. In each experiment, 6 test cups with mosquito larvae were exposed to six different concentrations of ivermectin (including the negative control). At the beginning of experiments, 25 third instar larvae were transferred from the larvae rearing pans to the labeled disposable plastic test cups with 100 ml of filtered non-chlorinated tap water by use of disposable Pasteur pipettes. By using a pipette with disposable tips, and starting with the lowest concentration, 1 ml of each of the six concentrations of ivermectin solutions were then added to the experimental cups (with mosquito larvae) thus giving final concentrations of 0.0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0 and 10.0 parts per million (ppm; equivalent to mg/liter), respectively. The test cups were held at 28 °C and photoperiods of 12 h light followed by 12 h darkness. Test larvae were provided with larval food at onset of each experiment. Larval mortality was recorded at 24 and 48 h after the addition of ivermectin solutions.

Data analysis

Data were entered in Excel and subsequently analyzed in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22). Survival of An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus was compared using Student’s t-test and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study received ethical approval from the Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research, Tanzania (Ref: NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/1554).

Results

Twelve replicates, each testing 6 concentrations of ivermectin (including the negative control) each with 25 larvae were conducted in parallel for a total of 1800 larvae of both An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus. The mean numbers (and range) of the two species surviving at the different ivermectin concentrations at 24 and 48 h post exposure is shown in Table 1.

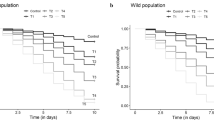

Survival was high in the control groups (0.0 ppm ivermectin concentration), being 100 % and 99.6 % for An. gambiae, and 100 % and 96.4 % for Cx. quinquefasciatus, at 24 and 48 h, respectively. In both species, larval survival declined markedly with increased ivermectin concentration (Fig. 1). For An. gambiae, the mean survival in 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 ppm ivermectin at 24 h was 99.6 % (P = 0.3), 99.2 % (P = 0.07), and 61.6 % (P < 0.001), and at 48 h was 95.2 % (P = 0.004), 81.1 % (P < 0.001), and 3.2 % (P < 0.001) respectively, when compared to the control group. No An. gambiae survived for 24 h in 1.0 and 10.0 ppm ivermectin. For Cx. quinquefasciatus, the mean survival in 0.001 and 0.1 ppm of ivermectin at 24 h was 89.2 % (P = 0.001) and 47.2 % (P = 0.001) and at 48 h it was 80.1 % (P = 0.001) and 18.7 % (P < 0.001), respectively, when compared to the control group. No Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae that survived for 24 h in 0.1, 1.0 or 10.0 ppm ivermectin.

Comparison between the species revealed that Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae were more susceptible to ivermectin than those of An. gambiae (Table 1). At 24 h, mean survival in An. gambiae was significantly higher than in Cx. quinquefasciatus at ivermectin concentration of 0.001 (P = 0.002) and 0.01 (P < 0.001) ppm. While ivermectin concentration of 0.1 ppm at 24 h caused 100 % mortality in Cx. quinquefasciatus, the same concentration caused only 38.4 % mortality in An. gambiae. At 48 h, the same pattern was seen, although mortality was higher in both groups.

Discussion

Ivermectin is generally considered one of the most beneficial biopharmaceutical drugs for use on a large scale in veterinary and human medicine [1]. Due to its therapeutic effectiveness and broad spectrum of activity in controlling many tropical parasitic diseases, it has been argued that the scope and use of this drug may possibly expand in the near future [25]. However, the broad spectrum of activity has also raised concerns with respect to its impact on non-target organisms in terrestrial and aquatic environments [5]. Of particular importance in mosquito larvae ecology, the bioavailability of ivermectin in aquatic environments is not homogeneous due to its low water solubility and association with sediments. This study assessed the sensitivity of insectary reared An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito larvae (known to feed in different levels of the water strata) to low concentrations of ivermectin under laboratory conditions.

Ivermectin concentrations in soil, groundwater, surface water and animal dung have previously been documented, and have been shown to vary with soil type and route and frequency of application to domestic animals [26]. Non-target organisms have shown variable sensitivity to ivermectin, with the cladoceran Daphnia magna being particularly sensitive with 50 % mortality after 48 h of exposure to a concentration of 0.0000057 ppm [27]. Relatively higher ivermectin concentrations of 0.18, 0.0075, 0.78 and 4.8 ppm were found to cause 50 % mortality in non-target Amphipoda, Polychaeta, Gastropoda and Actinopterygii, respectively [28–31]. A number of studies have indicated that photo-degradation on water surface and rapid adsorption of ivermectin to sediments play key roles in determining the bioavailability and environmental fate of ivermectin [32, 33]. Other studies have indicated that benthic microcrustaceans and nematodes generally are more sensitive to ivermectin than non-benthic organisms [27, 34], and this has been argued to be due to strong binding of ivermectin to soil particles thus rendering sediment-dwelling and benthic organisms particularly exposed [35].

In the current study, the survival of both An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae declined markedly with increase in ivermectin concentration at both 24 and 48 hours. The study thus confirmed previous observations indicating that ivermectin at low concentrations impairs the survival of larvae of Cx. quinquefasciatus [21, 22, 36], and that an ivermectin-related compound ‘spinosad’ (also a macrocyclic lactone) can be effective in controlling both anopheline and culicine mosquito larvae [37–39]. The current study moreover revealed that Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae were more susceptible to ivermectin than those of An. gambiae at both exposure times. For example, after 24 hours of exposure, an ivermectin concentration of 0.1 ppm caused 100 % larval mortality in Cx. quinquefasciatus but only 38.4 % mortality in An. gambiae. Our findings thus corroborate with those of Romi et al. [38] who showed that the bioinsecticide spinosad impacted more marked activity against larvae of Culex and Aedes than against those of Anophelines.

Inversely, previous experiments with adult mosquitoes of the same two species showed that blood meals taken from ivermectin treated humans significantly reduced survival of An. gambiae but had no effect on Cx. quinquefasciatus [10]. The reason for this reduced sensitivity of adult Cx. quinquefasciatus to ivermectin in blood meals is a subject for further research. However, the difference in susceptibility to ivermectin in aqueous environments between larvae of the same two species of mosquitoes may in part be associated with the physical properties of ivermectin of low water solubility and rapid adsorption to sediments [15, 16], in combination with the sedimentation of the larval feeds. Thus, it is likely that the larval food particles that sink increase ivermectin bioavailability at the bottom while depleting the same at the water surface. Being surface feeders, An. gambiae larvae would be less exposed to ivermectin than the bottom feeding Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae. Although it cannot be excluded that Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae are inherently more susceptible to ivermectin than An. gambiae larvae, it appears likely that the former species is considerably more exposed to the drug due to its bottom feeding habit, and that this may be a major cause for the higher mortality observed for this species. More studies should be carried out in controlled environments to confirm to what extent feeding and dwelling characteristics determine the survival of mosquito larvae in ivermectin contaminated habitats. Field studies should also be undertaken to examine to what extends breeding sites are contaminated in areas with ivermectin mass drug administration and its effect on mosquito larvae.

Conclusions

Low concentrations of ivermectin in the aquatic environment reduced the survival of larvae of An. gambiae and Cx. quinquefasciatus, with the effect being more marked in the latter than the former species. As ivermectin has low water solubility and adsorb rapidly to sediments in aquatic environment, this difference in mosquito survivorship may be due to the bottom feeding Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae being more heavily exposed to ivermectin than the surface feeding An. gambiae larvae. The observed effects on the larvae suggest that ivermectin finding its way to the environment after administration to humans or animals could indirectly affect the vector populations, with different effect on different species, and thereby the transmission of mosquito-borne infections.

References

Crump A. The advent of ivermectin: people, partnerships, and principles. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:423–45.

Omura S, Crump A. The life and times of ivermectin - a success story. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:984–9.

Ottesen EA, Hooper PJ, Bradley M, Biswas G. The global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: health impact after 8 years. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e317.

Geary TG. Ivermectin 20 years on: Maturation of a wonder drug. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:530–2.

Lumaret J-P, Errouissi F, Floate K, Römbke J, Wardhaugh K. A Review on the Toxicity and Non-Target Effects of Macrocyclic Lactones in Terrestrial and Aquatic Environments. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:1004–60.

Chaccour C, Lines J, Whitty CJM. Effect of ivermectin on Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes fed on humans: the potential of oral insecticides in malaria control. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:113–6.

Sylla M, Kobylinski KC, Gray M, Chapman PL, Sarr MD, Rasgon JL, Foy BD. Mass drug administration of ivermectin in south-eastern Senegal reduces the survivorship of wild-caught, blood fed malaria vectors. Malar J. 2010;9:365.

Kobylinski KC, Sylla M, Chapman PL, Sarr MD, Foy BD. Ivermectin mass drug administration to humans disrupts malaria parasite transmission in Senegalese villages. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:3–5.

Fritz ML, Siegert PY, Walker ED, Bayoh MN, Vulule JR, Miller JR. Toxicity of blood meals from ivermectin-treated cattle to Anopheles gambiae s.l. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:539–47.

Derua YA, Kisinza WN, Simonsen PE. Differential effect of human ivermectin treatment on blood feeding Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:130.

Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, da Silva IM, Rasgon JL, Sylla M. Endectocides for malaria control. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:423–8.

Chaccour CJ, Kobylinski KC, Bassat Q, Bousema T, Drakeley C, Alonso P, Foy BD. Ivermectin to reduce malaria transmission: a research agenda for a promising new tool for elimination. Malar J. 2013;12:153.

Alvinerie M, Sutra JF, Galtier P, Lifschitz A, Virkel G, Sallovitz J, et al. Persistence of ivermectin in plasma and faeces following administration of a sustained-release bolus to cattle. Res Vet Sci. 1999;66:57–61.

Boxall ABA, Fogg LA, Blackwell PA, Kay P, Pemberton EJ, Croxford A. Veterinary medicines in the environment. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2004;180:1–91.

Löffler D, Römbke J, Meller M, Ternes TA. Environmental fate of pharmaceuticals in water/sediment systems. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:5209–18.

Escher BI, Berger C, Bramaz N, Kwon J-H, Richter M, Tsinman O, et al. Membrane-water partitioning, membrane permeability, and baseline toxicity of the parasiticides ivermectin, albendazole, and morantel. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008;27:909–18.

Sanderson H, Laird B, Pope L, Brain R, Wilson C, Johnson D, et al. Assessment of the environmental fate and effects of ivermectin in aquatic mesocosms. Aquat Toxicol. 2007;85:229–40.

Meyrowitsch DW, Pedersen EM, Alifrangis M, Scheike TH, Malecela MN, Magesa SM, Derua YA, Rwegoshora RT, Michael E, Simonsen PE. Is the current decline in malaria burden in sub-Saharan Africa due to a decrease in vector population? Malar J. 2011;10:188.

Derua YA, Alifrangis M, Hosea KMM, Meyrowitsch DW, Magesa SM, Pedersen EM, Simonsen PE. Change in composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex and its possible implications for the transmission of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2012;11:188.

World Health Organization. Manual on practical entomology in malaria. Part 1. Vector bionomics and organization of anti-malaria activities. Geneva: WHO; 1975.

Alves SN, Serrão JE, Mocelin G, de Melo AL. Effect of ivermectin on the life cycle and larval fat body of Culex quinquefasciatus. Brazilian Arch Biol Technol. 2004;47:433–9.

de Freitas RMC, Faria MDA, Alves SN, de Melo AL. Effects of ivermectin on Culex quinquefasciatus larvae. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1996;38:293–7.

Benedict MQ. Methods in Anopheles research. 4th ed. Atlanta: CDC; 2014.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides. WHO Pesticides Evaluation Scheme. WHO/CDS/WHOPES/GCDPP/2005.13. Geneva: WHO; 2005.

Omura S, Crump A. Ivermectin: panacea for resource-poor communities? Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:445–55.

Liebig M, Fernandez AA, Blübaum-Gronau E, Boxall A, Brinke M, Carbonell G, et al. Environmental risk assessment of ivermectin: A case study. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2010;6 Suppl 1:567–87.

Garric J, Vollat B, Duis K, Péry A, Junker T, Ramil M, et al. Effects of the parasiticide ivermectin on the cladoceran Daphnia magna and the green alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata. Chemosphere. 2007;69:903–10.

Davies IM, Gillibrand PA, McHenery JG, Rae GH. Environmental risk of ivermectin to sediment dwelling organisms. Aquaculture. 1998;163:29–46.

Grant A, Briggs AD. Toxicity of ivermectin to estuarine and marine invertebrates. Mar Pollut Bull. 1998;36:540–1.

Davies IM, Rodger GK. A review of the use of ivermectin as a treatment for sea lice [Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Krøyer) and Caligus elongatus Nordmann] infestation in farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquac Res. 2000;31:869–83.

Halley BA, Jacob TA, Lu AYH. The environmental impact of the use of ivermectin: environmental effects and fate. Chemosphere. 1989;18:1543–63.

Halley BA, VandenHeuvel WJ, Wislocki PG. Environmental effects of the usage of avermectins in livestock. Vet Parasitol. 1993;48:109–25.

Prasse C, Löffler D, Ternes TA. Environmental fate of the anthelmintic ivermectin in an aerobic sediment/water system. Chemosphere. 2009;77:1321–5.

Brinke M, Höss S, Fink G, Ternes TA, Heininger P, Traunspurger W. Assessing effects of the pharmaceutical ivermectin on meiobenthic communities using freshwater microcosms. Aquat Toxicol. 2010;99:126–37.

Krogh KA, Björklund E, Loeffler D, Fink G, Halling-Sørensen B, Ternes TA. Development of an analytical method to determine avermectins in water, sediments and soils using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1211:60–9.

Alves SN, Tibúrcio JD, de Melo AL. Suscetibilidade de larvas de Culex quinquefasciatus a diferentes inseticidas. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44:486–9.

Antonio GE, Sánchez D, Williams T, Marina CF. Paradoxical effects of sublethal exposure to the naturally derived insecticide spinosad in the dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Pest Manag Sci. 2009;65:323–6.

Romi R, Proietti S, Di Luca M, Cristofaro M. Laboratory evaluation of the bioinsecticide Spinosad for mosquito control. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2006;22:93–6.

Marina CF, Bond J, Muñoz J, Valle J, Chirino N, Williams T. Spinosad: a biorational mosquito larvicide for use in car tires in southern Mexico. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:95.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the laboratory staff at the Amani Research Centre (Demitrius A. Max, Josephine Nyongole, Stephen Mkongewa, Isaya Kibwana and Kisesa Kassim) for raising the larvae and to John Samwel Fundi for assisting in assembling tools required for the bioassays. The study received financial support from the Danida Research Council, Denmark (FFU grant #09-096LIFE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PES and YAD conceived and designed the study. YAD and BBM coordinated the laboratory experiments. YAD drafted the manuscript with contributions from PES and BBM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Derua, Y.A., Malongo, B.B. & Simonsen, P.E. Effect of ivermectin on the larvae of Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus . Parasites Vectors 9, 131 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1417-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1417-5