Abstract

Background

Pretreatment is a vital step upon biochemical conversion of lignocellulose materials into biofuels. An acid catalyzed thermochemical treatment is the most commonly employed method for this purpose. Alternatively, ionic liquids (ILs), a class of neoteric solvents, provide unique opportunities as solvents for the pretreatment of a wide range of lignocellulose materials. In the present study, four ionic liquid solvents (ILs), two switchable ILs (SILs) DBU–MEA–SO2 and DBU–MEA–CO2, as well as two ‘classical’ ILs [Amim][HCO2] and [AMMorp][OAc], were applied in the pretreatment of five different lignocellulosic materials: Spruce (Picea abies) wood, Pine (Pinus sylvestris) stem wood, Birch (Betula pendula) wood, Reed canary grass (RCG, Phalaris arundinacea), and Pine bark. Pure cellulosic substrate, Avicel, was also included in the study. The investigations were carried out in comparison to acid pretreatments. The efficiency of different pretreatments was then evaluated in terms of sugar release and ethanol fermentation.

Results

Excellent glucan-to-glucose conversion levels (between 75 and 97 %, depending on the biomass and pretreatment process applied) were obtained after the enzymatic hydrolysis of IL-treated substrates. This corresponded between 13 and 77 % for the combined acid treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis. With the exception of 77 % for pine bark, the glucan conversions for the non-treated lignocelluloses were much lower. Upon enzymatic hydrolysis of IL-treated lignocelluloses, a maximum of 92 % hemicelluloses were also released. As expected, the ethanol production upon fermentation of hydrolysates reflected their sugar concentrations, respectively.

Conclusions

Utilization of various ILs as pretreatment solvents for different lignocelluloses was explored. SIL DBU–MEA–SO2 was found to be superior solvent for the pretreatment of lignocelluloses, especially in case of softwood substrates (i.e., spruce and pine). In case of birch and RCG, the hydrolysis efficiency of the SIL DBU–MEA–CO2 was similar or even better than that of DBU–MEA–SO2. Further, the IL [AMMorp][OAc] was found as comparably efficient as DBU–MEA–CO2. Pine bark was highly amorphous and none of the pretreatments applied resulted in clear benefits to improve the product yields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Second-generation biorefineries based on the exploitation of lignocellulose as the main carbon source, have the potential to produce a variety of products, including bio-fuels, value-added chemicals, materials, heat and electricity [1–3]. However, laboratory scale experiments often report limited product yields due to the complex structure and high crystallinity of the feedstock. As known, lignocelluloses are mainly composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. Cellulose and hemicelluloses are carbohydrate polysaccharides while lignin is a complex aromatic polymer [4]. In combination, these three main components form a complex structure of vegetal biomass. In a typical biomass conversion process, the raw material is pre-treated to improve the accessibility of polysaccharides for their further conversion into monosaccharides. This is typically performed via processing of biomass in environmentally harmful chemicals, such as sulfuric acid that facilitates the hydrolysis and extraction of sugars leaving most of the lignin in the solid residue. Alternatively, lignin can be removed by the use of alkaline solutions or organic solvents, leaving solids rich in sugar polysaccharides. Already, a number of pretreatment methods based on the use of different solvents, e.g., acids, alkali, organic solvents and/or other techniques like steam explosion, ammonia fiber explosion, etc. have been introduced for lignocellulose disruption and are well reviewed [5–11]. The lignin-rich residues obtained from an acid pretreatment can be used as low-value boiler fuel to produce heat and electricity [12]. Moreover, lignin can also be considered as a valuable source of carbon and if selectively removed and recovered it can be used to produce high value derivatives ([5, 6, 13]). After completed pretreatment, enzymes can be used to further degrade and hydrolyze the polysaccharides into monosaccharides which can then be used to produce various products such as alcoholic fuels (e.g., ethanol, butanol) via fermentation [14–17].

If the applied pretreatment is inefficient, the downstream hydrolysis and fermentation are likely to give low product yields [12]. Pretreatment is, therefore, a very important step in lignocellulose conversion processes. Thus, the refinement of lignocellulose pretreatment technologies is necessary to further facilitate enzymatic degradation of polysaccharides, improve product yields, and move closer to an economically viable lignocellulose biorefinery.

Ionic liquids (ILs), salts composed of organic cations and either organic or inorganic anions [18]; these neoteric solvents have lately attracted significant attention due to their ability to dissolve a wide range of organic and inorganic compounds, including lignocellulosic materials [19, 20]. Because of their unique physicochemical properties and potential for associated environmental benefits, ILs are considered to be of interest as potential alternatives to the traditional lignocellulose pretreatment solvents and a variety of ILs have been applied in fractionation and dissolution different lignocelluloses [6, 8, 21–23]. Nevertheless, many ILs are expensive [24] and biomass treatment was in many cases performed at rather low temperatures and with retention times of up to several days [6]. Thus, design of low-cost ILs [24] that efficiently work at high temperatures and with a short processing time is of interest. Among the investigated ones, the use of inexpensive acidic ILs that can be produced on bulk scale is potentially a sustainable approach of lignocellulosic biomass conversion without addition of catalyst [25, 26].

The new acidic switchable ILs (SILs) DBU–MEA–SO2 (DBU: 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene; MEA: monoethanolamine) and DBU–MEA–CO2 have been reported to be efficient for optimal fractionation and selective removal of almost all lignin from the Nordic woody biomass [27, 28]. In addition, among the more commonly applied cellulose-dissolving ILs (CILs) such as [C2mim][OAc] [29–32] and [C4mim]Cl [29, 30], [Amim][HCO2] and [AMMorp][OAc] were proven to be efficient for the dissolution of lignocellulose substrates [33, 34]. Hence, the present study focuses on investigation of above mentioned four (S)ILs in pretreatment, at high temperatures and with a short processing time.

Results

Chemical composition of different lignocelluloses

The composition of structural carbohydrates, lignin and extractives of different lignocelluloses used in this study are presented in Table 1. The values in Table 1 are comparable to those reported in the literature [7, 35–37]. Softwood substrates, i.e., spruce and pine, are rich in glucomannans, while both birch (a hard wood substrate) and reed canary grass are rich in glucoxylanes (Table 1). On the contrary, pine bark contains high amounts of arabinoglucans (Table 1). As expected, lignin content of softwood substrates was higher than that of hardwood and reed canary grass. Nevertheless, pine bark displayed the highest lignin content of 40.3 % (dry wt). Pine bark was also exclusively rich in extractives [19.4 % (dry wt)] while the extractives content of other substrates was maximally 4 % (dry wt) (Table 1).

Enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated and non-treated Avicel cellulose

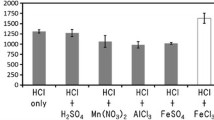

In Initial experiments, a model crystalline cellulose Avicel was treated with various IL solvents at a severity factor (SF) of 2.5 and subsequently subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis. As control, Avicel was hydrolyzed without any pretreatment. After 48 h of enzymatic hydrolysis, the glucose yields (g glucose released/g maximum available glucose) were 0.68, 0.69, 0.81, 0.70, and 0.80 for the non-treated and the samples treated with DBU–MEA–SO2, DBU–MEA–CO2, [Amim][HCO2] and [AMMorp][OAc], respectively. Compared to non-treated material, the glucose production rates (GPRs, calculated from the first 4 h of hydrolysis) were 44, 10 and 42 % higher for the Avicel treated with DBU–MEA–CO2, [Amim][HCO2] and [AMMorp][OAc], respectively (Fig. 1). Hence, use of DBU–MEA–CO2 and [AMMorp][OAc] resulted in most successful treatments for Avicel cellulose, whereas treatment with DBU–MEA–SO2 did not result in any improvement in subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of non-treated, acid pre-hydrolyzed, and IL-treated lignocellulose substrates

Soft wood substrates

In case of softwood substrates such as spruce wood and pine stem wood, an acid pre-hydrolysis was not beneficial for the subsequent enzymatic degradation (Figs. 2a, b, 4a, b). The GPRs (~0.6 g L−1 h−1) and the glucose yields (11–13 %) were similar for the enzymatic hydrolysis of non-treated and the solids of acid pre-hydrolysis (S-APH).

Glucose production rates (GPRs) during 4-h enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose substrates. a Spruce wood; b Pine stem wood; c Birch wood. Enzymatic hydrolysis experiments were performed with either non-treated or H2SO4-treated (SF 4.1), or (S)IL-treated lignocelluloses. (S)IL treatments were performed at (A) SF 2.5 (B) SF 3.7 and (C) SF 4.1

Glucose production rates (GPRs) during 4-h enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose substrates. a Reed canary grass; and b Pine bark. Enzymatic hydrolysis experiments were performed with either non-treated or H2SO4-treated (SF 4.1), or (S)IL-treated lignocelluloses. (S)IL treatments were performed at (A) SF 2.5 (B) SF 3.7 and (C) SF 4.1

Sugar yield (g sugars released/g available sugars) obtained from the hydrolysis of lignocellulose materials. Blue bars represent glucose and yellow bars represent total reducing sugars. a Spruce wood; b Pine stem wood; c Birch wood. Enzymatic hydrolysis experiments were performed with either non-treated or H2SO4-treated (SF 4.1), or (S)IL-treated lignocelluloses. (S)IL treatments were performed at (A) SF 2.5 (B) SF 3.7 and (C) SF 4.1. AH is acid hydrolysate, i.e., liquid fraction obtained from the acid pre-hydrolysis and EH is enzymatic hydrolysate of acid-treated solids

Sugar yield (g sugars released/g available sugars) obtained from the hydrolysis of lignocellulose materials. Blue bars represent glucose and yellow bars represent total reducing sugars. a Reed canary grass; and b Pine bark. Enzymatic hydrolysis experiments were performed with either non-treated or H2SO4-treated (SF 4.1), or (S)IL-treated lignocelluloses. (S)IL treatments were performed at (A) SF 2.5 (B) SF 3.7 and (C) SF 4.1. AH is acid hydrolysate, i.e., liquid fraction obtained from the acid pre-hydrolysis and EH is enzymatic hydrolysate of acid-treated solids

Compared with both non-treated and acid pre-hydrolyzed, softwood substrates originating from IL treatments were readily degraded by enzymes—hydrolysis rates were significantly enhanced and high sugar conversions were observed (Figs. 2a, b, 4a, b). Upon enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated substrates, the GPRs and glucose yields were enhanced to a maximum of 1.1–2.7 g L−1 h−1 and 28–75 % for spruce wood, and 1.3–3.6 g L−1 h−1 and 39–93 % for pine stem wood. In addition, the hemicellulose recovery 61 and 71 % from the enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL spruce and pine, respectively, were slightly higher than that of 57 and 65 % recovered from the combined acid pre-hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis.

DBU–MEA–SO2 was the best solvent for the pretreatment of softwood substrates, followed by DBU–MEA–CO2 and [AMMorp][OAc]. It should be noted, that IL [AMMorp][OAc] appeared to be in the same magnitude of order as DBU–MEA–CO2.

Hardwood substrate

Acid pre-hydrolysis of hard wood such as birch was beneficial and improved the subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis (Figs. 2c, 4c). The GPR increased from 0.5 to 0.7 g L−1 h−1 and the glucose yields from 10 to 20 % in S-APH samples compared to non-treated birch wood.

Similar to softwoods, enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated birch wood was highly efficient. A maximum GPR of 1.4–4.3 g L−1 h−1 and glucose yields of 47–96 % were obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated birch wood (Figs. 2c, 4c). In fact, the hemicellulose recovery max 92 % from the enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated birch wood was comparably higher than the 56 % recovered from the combined acid pre-hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis of birch wood. The tendency of (S)ILs efficiency for birch wood was similar to that of softwood substrates, but the sugar yields (glucose 95–96 %, overall 93–94 %) were similar irrespective of whether they were DBU–MEA–SO2 or DBU–MEA-CO2 (Fig. 4c). However, the GPR maximum 3.3 g L−1 h−1 for the DBU–MEA–CO2-treated birch wood was lower than the 4.3 g L−1 h−1 of DBU–MEA–SO2-treated substrate. The glucose yields for the [AMMorp][OAc]-treated birch wood also reached as high as 91 %, but the maximum GPR was only 2.3 g L−1 h−1.

Agricultural residues

Surprisingly, unlike any investigated lignocellulose substrates, no sugars were released from the enzymatic hydrolysis of non-treated reed canary grass (Figs. 3a, 5a). However, acid pre-hydrolysis of reed canary grass significantly improved its subsequent enzymatic degradation. Enzymatic hydrolysis of S-APH of reed canary grass resulted in 47 % glucose yield with a GPR of 1.8 g L−1 h−1.

The hydrolysis efficiency of reed canary grass was further enhanced by (S)IL treatments. Upon enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated reed canary grass, a maximum GPRs of 2.1–4.6 g L−1 h−1 and glucose yields of 55–97 % were obtained. For reed canary grass, both SILs DBU–MEA–SO2 and DBU–MEA–CO2 were similarly efficient in terms of GPRs and yields. Even though, IL [AMMorp][OAc] was as efficient as SILs still the GPRs for [AMMorp][OAc] treated reed canary grass were slightly lower than for the S-ILs-treated substrates. However, at less sever treatment conditions (i.e. SF 2.5), DBU–MEA–CO2 was better solvent than other (S)ILs, resulting a 4.3 g L−1 h−1 GPR and 94 % glucose yield. Nonetheless, the hemicellulose recovery from the (S)ILs-treated reed canary grass 71 % was lower than the 90 % of recovered from the combined acid pre-hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis.

Pine bark

Enzymatic hydrolysis of non-treated pine bark was readily degraded, as smoothly as samples pre-treated with either acid or any ILs, by cellulase enzymes (Figs. 3b, 5b) giving a GPR of 1.5 g L−1 h−1 and glucose yield of 77 %. Compare to non-treated, acid pre-hydrolysis or (S)IL treatment of pine bark had no or only minimal effect on its subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis. Treatment with S-ILs slightly beneficial and improved GPRs max. 2.2 g L−1 h−1 and glucose yield max. 88 % g L−1 glucose.

However, the hemicellulose recovery 88 % and overall sugar yield 83 % obtained from the acid pre-hydrolysis were significantly higher than obtained from either non-treated (17 or 45 %) or (S)IL-treated (23 and 53 %).

Separate hydrolysis and fermentation of different lignocelluloses after treatment with either sulfuric acid or a SIL DBU–MEA–SO2

Hydrolysates obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of DBU–MEA–SO2 treated or acid pre-hydrolyzed substrates were readily fermented to ethanol. Glucose present in the hydrolysates was completely consumed and converted to ethanol within first 10 h of fermentations (Fig. 6). Ethanol concentrations of 1.2, 1.3, 1.8, 3.5, and 2.7 g L−1 were obtained from the fermentation of enzymatic hydrolysates of acid pre-hydrolyzed spruce wood, pine stem wood, birch wood, reed canary grass, and pine bark, respectively. The corresponding values for the DBU–MEA–SO2 treated substrates were 3.2, 4.6, 7.2, 7.6, and 3.5 g L−1, respectively. Even though the overall sugar production was higher for the combined acid and enzymatic hydrolyzed pine bark (Fig. 5b), still the overall ethanol production 3.4 g L−1 (0.7 g L−1 from acid hydrolysates and 2.7 g L−1 from enzymatic hydrolysates) did not exceed that obtained from the hydrolysates of IL-treated substrate (Fig. 6). Evidently, hemicellulose sugars of acid pre-hydrolysates were not consumed by the microorganism S. cerevisiae and requires an engineered strain that could use not only glucose but also other lignocellulose derived sugars.

Ethanol produced from the fermentations of lignocellulose hydrolysates. Green bars represent ethanol produced from the enzymatic hydrolysates and red bars represent ethanol produced from the liquid fraction of acid pre-hydrolysis. Enzymatic hydrolysis experiments were performed with lignocellulose that were first treated with either H2SO4 (SF 4.1) or with the SIL DBU–MEA–SO2 (SF 4.1)

Discussion

Non-treated and acid pre-hydrolyzed substrates

The acid pre-hydrolysis procedure, used in our study is known to produce enzymatically digestible biomass, did not benefit the subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis of especially softwood substrates. This observation is, however, consistent with observations reported by Ungurean et al. [2]. Compared to non-treated, less sugars were released from the enzymatic hydrolysis of acid pre-hydrolyzed fir wood [2]. However, the main role of dilute acid pretreatment is to solubilize hemicellulose from the biomass and to make cellulose more accessible for cellulases [2] which is also evident from our study (see Additional file 1: Tables S1–S5). The resistance of acid pre-hydrolyzed material to the hydrolytic enzymes was probably due to the changes in substrate crystallinity and increased enzyme binding capacity of lignin—the major feature that affects enzymatic degradation process [38].

Li et al. [39] investigated the efficiency of dilute acid treatment of lignocellulose substrate. Results indicated that both non-treated and dilute acid-treated samples display no changes in cellulose structure. Also, significant amount of lignin remained in the acid-treated material. Upon enzymatic hydrolysis, cellulases tend to bind on the lignin-rich surfaces—lignin can irreversibly adsorb cellulases [40] causing loss of cellulose degradation. In addition, acid treatment of spruce wood altered the lignin structure leading to increased enzyme adsorption [41, 42]. Moreover, after acid treatment, lignin or lignin carbohydrate complexes may condense on the surface of cellulose fibers [43], thus rendering the fibers less accessible to enzymes.

However, the positive effect of acid pretreatments of birch wood and canary grass could be attributed to their lignin content which contained less lignin than the softwood substrates (Table 1). However, the inhibition of enzymes lignin did not comply for pine bark. Although pine bark contained high amounts of lignin (40.3 % dry wt.), the non-treated substrates were readily degraded by cellulase enzymes.

Effect of IL treatments

Anugwom et al. [27, 28] investigated the efficiency of SILs MEA–DBU–SO2 and MEA–DBU–CO2 for the fractionation of woody biomass (i.e. spruce and birch) and reported that both these solvents could remove lignin and produce glucan enriched pulps. However, SILs MEA–DBU–SO2 was a better solvent than MEA–DBU–CO2, since it was capable of removing more than 90 % of lignin present in the native substrates whereas MEA–DBU–CO2 could remove only up to 50 % [28]. Furthermore, regeneration of substrates via addition of water as anti-solvent (which is performed in our study) could reject the ILs soluble lignin in the solution [44]. Thus, creating a large cellulose accessible surface area for the subsequent enzymatic degradation with no lignin related enzyme inhibition. The improved enzymatic degradation of MEA–DBU–SO2 was more likely due to its capacity in selectively removing high amounts of lignin rather than its effect on cellulose crystallinity. In case of MEA–DBU–CO2, the improved enzymatic hydrolysis is believed to be due to its synergistic effects. MEA–DBU–CO2 is not only capable of removing lignin but also could reduce cellulose crystallinity as evident from the experiments with Avicel cellulose. However, MEA–DBU–CO2 treatment of soft wood substrates was less effective probably due to its low lignin removing capacity.

Unlike SILs, [AMMorp][OAc] does not remove lignin. Thus, obviously, the GPRs for the [AMMorp][OAc] treated substrates were lower than the SILs-treated substrates (Figs. 2, 3). However, lignin recovery from [AMMorp][OAc]-treated substrates is rather simple whereas it would require additional efforts in case of SILs. The effect of IL [Amim][HCO2] treatments were significantly lower than the any investigated (S)ILs. This is because [Amim][HCO2] was less efficient in dissolving cellulose and it does not remove any lignin.

Nevertheless, despite the potential, recovery and reuse of ILs are important to make the process economically feasible. ILs are still more expensive than the conventional pretreatment solvents [6]. The recycling of ILs up to 10–20 times was claimed to allow for process costs per cycle comparable to conventional solvents, hence making ILs as cheaper alternatives as reusable solvents [45]. ILs are comparatively easy to recycle by simply removing the anti-solvent using techniques such as evaporation or distillation [19, 46, 47]. The low-volatile nature of ILs permits distillation of the volatile substances, thus allowing for recovery [48, 49]. It has been already shown that the ILs can be recovered and reused at least up to 5–7 times without decline in their efficiency [22, 49]. However, recovery and reuse of ILs are often a question considering scaled up production of ILs. Nonetheless, ILs that have undergone cellulose regeneration are composed of not only dissolved IL and the anti-solvent but also contain soluble biomass compounds (e.g., lignin, soluble carbohydrates with low molecular weight, degradation products, extractives and others) that were not precipitated in the regeneration step. Recovery of these dissolved compounds is important; for instance, the recovered lignin may potentially serve as a raw material in the production of polymeric materials, and can be tedious.

Influence of IL treatment conditions on enzymatic hydrolysis

The conditions used for the IL treatments (Table 2) were selected to gain more information about the impact of treatment temperature and residence time on the IL treatments effect on subsequent substrate hydrolysis efficiency.

At a constant amount, i.e., 5 (w/w) % of biomass loading and upon fixed (S)IL pretreatment time, increasing pretreatment temperature favored and greatly enhanced the enzymatic digestion of lignocellulose substrates similar to observations by Hou et al. [50]. After IL treatment of birch and pine wood, at moderate conditions, the substrates were swollen but not dissolved [51]. It is believed that, at low pretreatment temperatures, the IL molecules mainly swell and disrupt cellulose I lattice, with no appreciable amount of cellulose chains being released into the IL solution. It is also speculated that, at low temperatures, the multilayered structures of plant cell wall and lignin network inhibit dissociation of cellulose chains [50]. However, at higher temperatures, the plant cell walls were destroyed and cellulose chains were released into the IL solution and the highly crystalline cellulose I was transformed into less crystalline cellulose II [52]. Hence, evidently, the highest amount of reducing sugars (and best glucose production rates) was obtained for the substrates treated at 160 and 180 °C (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5). Shorter (S)IL treatment time (instead of 90 min 60 min) an increase in temperature (from 160 to 180 °C) had no significant effect in terms of subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis. In conclusion, high temperatures and short residence time upon pretreatment of lignocelluloses gave good results.

In general, from our study it was clear that, except or pine bark, lignin is a major barrier and plays an important role in the sugar extraction from lignocellulose substrates. There was a very close correlation between effect of efficiency of pretreatment solvent and lignin content of the lignocellulose. For example for lignin-rich soft wood substrates, lignin-specific SIL DBU–MEA–SO2 was the most efficient pretreatment solvent. Nevertheless, in case of the species with low lignin content (hard wood and reed canary grass), DBU–MEA–CO2 or [AMMorp][OAc] was the best pretreatment medium. Evidently, the differences in the substrate lignin content have an impact on the results of any pretreatment as reported before [53].

Conclusions

The potential of different (S)ILs as pretreatment solvents upon conversion of several lignocelluloses into bioethanol was investigated. It was demonstrated that (S)IL treatments could significantly improve the enzymatic hydrolysis of biomass. SILs were in relative terms better pretreatment solvents, especially in case of softwood substrates. The SIL DBU–MEA–SO2 was the best pretreatment media for woody substrates liberating both glucose and hemicellulose sugars. Nevertheless, in case of Pine bark, the combined acid treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis gave better results than what could be achieved with any (S)IL preprocessing. However, hydrolysates obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of (S)IL-treated lignocelluloses were readily fermented to ethanol and the yields were up to four times higher compared to the case when combined acid and enzymatic hydrolysis was employed. Thus, (S)IL-mediated preprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass can offer advantages over conventional acid treatments.

However, even though the (S)ILs investigated in this study were highly efficient, still challenges remain in their applications such as recovery of any (S)IL-degraded species (notably lignin and sugar polysaccharides) and potentially challenging recycling of (S)ILs.

Methods

Substrates

A variety of lignocellulose materials, including those of soft wood, hard wood and agriculture residues were targeted in the current study. Norway spruce wood, pine stem wood, birch saw dust, pine bark, and reed canary grass were the species studied. The substrates were first air dried at room temperature until a constant weight and moisture content less than 10 (w/w) %, was achieved. Afterwards, they were milled and sieved to an even particle size <1 mm using a Wiley mill and stored in sealed plastic bags at room temperature until further use. The dry-matter content of the substrates was determined using a Sartorius MA30 Electronic Moisture Analyzer (Germany) through heating by infrared rays and determination of weight loss. Along with native lignocellulose materials, a commercial microcrystalline cellulose substrate Avicel® PH-101 (Sigma-Aldrich) was also used in the investigation for the sake of comparison.

The chemical composition of lignocelluloses in terms of structural carbohydrate content, lignin and extractives were analyzed according to National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) analytical procedures [54, 55].

Ionic liquids

SILs DBU–MEA–SO2 and DBU–MEA–CO2 were prepared as described in Anugwom et al. [27, 28]. An equimolar mixture of DBU and MEA was bubbled with either SO2 or CO2 gas under rigorous stirring and the reactions were performed until the complete formation of SILs. [Amim][HCO2] was synthesised as reported earlier in Soudham et al. [33].

The new IL [AMMorp][OAc] was prepared as follows: Amberlite IRA-400(R-OH) (10.0 g in deionized water) was loaded in a chromatography column (20 × 1.5 cm) and then 1.0 M sodium acetate solution (100 mL) was passed through the column to facilitate ion exchange. After, the column was thoroughly washed with deionized water until the eluent pH ~7 was obtained. The corresponding bromide precursor, N-allyl-N-methylmorpholinium bromide (4.44 g in 50 mL deionized water), solution was carefully loaded and passed through the column followed by deionized water (50 mL). The eluent containing [AMMorp][OAc] was collected and water evaporated. Then the IL was dried at 60 °C under high vacuum (4 × 10−2 mbar) to remove residual water.

Pretreatment procedures

Pretreatment of different cellulosic substrates (50 mg) with either various IL solvents (950 mg) or 1 (w/w) % H2SO4 (950 mg) were performed in 12 mL borosilicate glass tubes with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-lined screw caps. A pressure reactor (Teflon lined stainless steel, homemade, 500 mL) with silicon oil was preheated to a desired treatment temperature using a furnace (T max < 1100 °C) equipped with B 180 controller and NiCr-Ni thermocouple (Nabertherm Muffle furnace, Model No. LVT 9/11, Germany). Glass tubes with cellulosic substrates and ionic liquids were then immersed into the preheated reactor and closed tightly. The reactor was then placed in the furnace and the desired reaction conditions were set (Table 2). After treatment, the reactor was removed from the furnace; the tubes were removed from the reactor and allowed to cool to room temperature. The IL-treated cellulose rich substrates were then precipitated by simply adding 6 g of anti-solvent (in our case deionized water) to the pretreated solutions. Afterwards, the solids were separated by vigorous mixing and centrifugation for 7 min and 3000 rpm (Allegra® 25R centrifuge, BECKMAN COULTER, USA). The IL rich supernatants were decanted and the solids were subsequently washed as described above, using 3 × 6 g anti-solvent and 1 × 6 g 50 mM citrate buffer pH 5.8. These are hereafter referred to as regenerated substrates. In the case of lignocelluloses pre-hydrolyzed with H2SO4, the solid and liquid fractions were separated by centrifugation. The collected liquid fractions (acid hydrolysates—AHs) were stored at –80 °C and the solids were washed with deionized water and citrate buffer as mentioned earlier. The obtained regenerated substrates from IL treatments and the solids from acid pre-hydrolysis (S-AH) were then lyophilized (Alpha 2-4 LSC Freeze Dryer, Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Germany) to remove any residual liquids, thus avoiding uneven dilutions upon their enzymatic hydrolysis.

To compare the efficiency of different treatments used in this study, the parameter severity factor (SF) was employed, which incorporates the treatment time and temperature (see the equation below). It is generally used to assess various individual lignocellulose pretreatment strategies [56].

In the above equation, t is the treatment time in minutes, T is the treatment temperature, T ref is the reference temperature (i.e., 100 °C) and 14.75 is an empirically determined constant.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

Enzymatic hydrolysis experiments of non-treated and regenerated cellulosic substrates were carried out in 12 mL glass tubes with 930 mg of 50 mM citrate buffer pH 5.8 and 20 mg of Cellic CTec2, activity 128.6 FPU/g, state-of-the-art enzyme mix (Novozymes). Hydrolysis reactions were performed for 48 h in a shaking incubator (IKA® KS 4000, control IKA®-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) set at 50 °C and 200 rpm. At defined time intervals (4, 24, and 48 h after the addition of enzymes), samples of 50 μL (enzymatic hydrolysates—EHs) were collected from the hydrolysis systems and stored at −80 °C.

Separate hydrolysis and fermentation

Lignocellulose samples, 0.25 g (dry weight), were pretreated at a severity factor of 4.1 (Table 2) with either the SIL DBU–MEA–SO2 (4.75 g) or 1 (w/w) % H2SO4 (4.75 g) in 10 mL glass tubes. Hydrolysis of regenerated substrates 0.3 g, obtained after the treatments and lyophilization, was performed in the presence of citrate buffer pH 5.8 (5.58 g) and enzyme (0.12 g) mix. Thus, the pretreatments and enzymatic hydrolysis experiments were performed (as described in earlier sections) with an increased overall reaction volume, but in equal concentrations. After enzymatic hydrolysis, the solid and liquid fractions were separated by centrifugation and the sugar-rich liquid fractions were used for ethanol fermentations as described below.

The yeast S. cerevisiae, Thermosacc inoculum was prepared in a 2 L cotton-plugged shake flask with 1 L YPD medium (10 g L−1 yeast extract, 20 g L−1 peptone, 20 g L−1 d-glucose). The medium was inoculated and incubated with agitation (200 rpm) at 30 °C and the cells were harvested in late exponential growth phase by centrifugation (Hermle Z206A, Hermle Labortechnik GmbH, Wehingen, Germany) at 1500g for 5 min. The harvested cells were concentrated and re-suspended in an appropriate amount of sterile water to achieve a cell density of 27 g L−1 (dry weight). Fermentations of liquid hydrolysates, obtained from both the acid pre-hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis, were performed in 12 mL screw capped plastic tubes. Sugar-rich liquid hydrolysates (2.3 mL of each) were added to the tubes along with 0.05 mL nutrient solution (75 g L−1 yeast extract, 37.5 g L−1 (NH4)2HPO4, 1.875 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 119.1 g L−1 NaH2PO4.H2O), and 0.15 mL of yeast inoculum. Thus, the fermentation broths contained a total liquid volume of 2.5 mL and had a yeast cell density of 1.6 g L−1 dry weight. After inoculation, the tubes were incubated at 30 °C and stirred (at 200 rpm) in an orbital shaking incubator (IKA-Werke) for 24 h. Samples of 100 µL were collected at defined time intervals and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

Analysis

Samples collected from different experiments of this study were centrifuged (Centrifuge: Thermo Scientific, Germany) at 21,000g for 5 min and the supernatants were used for chemical analysis by either using ion chromatography (IC; ICS 3000, Dionex Corporation, USA) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC; DionexTM UltiMate 3000, Dionex Corporation, USA).

The monosaccharide (i.e., arabinose, galactose, glucose, mannose, and xylose) concentrations were analyzed in a similar manner as in Wang et al. [57] by Ion Chromatography using a CarboPac PA1 column (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Ethanol concentrations were measured by HPLC equipped with a Rezex ROA-Organic acid H column (containing sulfonated styrene–divinylbenzene spheres in 8 % cross-link forms, 300 × 7.8 mm, Phenomenex®, USA) as previously described in Soudham et al. [58].

Abbreviations

- [Amim][HCO2]:

-

1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium formate

- [AMMorp][OAc]:

-

N-allyl-N-methylmorpholinium acetate

- [C2mim][OAc]:

-

1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate

- [C4mim]Cl:

-

1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride

- AH:

-

acid hydrolysate

- DBU:

-

1,8-diazabicycloundec-7-ene

- EH:

-

enzymatic hydrolysate

- GPR:

-

glucose production rate

- IL:

-

ionic liquid

- MEA:

-

monoethanolamine

- RCG:

-

reed canary grass

- S-APH:

-

solids obtained from the acid pre-hydrolysis

- SF:

-

severity factor

- SIL:

-

switchable ionic liquid

References

Binder JB, Raines RT (2010) Fermentable sugars by chemical hydrolysis of biomass. PNAS Appl Biol Sci Chem 107:4516–4521

Ungurean M, Fiţigău F, Paul C, Ursoiu A, Peter F (2011) Ionic liquid pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of wood biomass. World Acad Sci Eng Technol 52:387–391

Ragauskas AJ, Beckham GT, Biddy MJ, Chandra R, Chen F, Davis MF, Davison BH, Dixon RA, Gilna P, Keller M, Langan P, Naskar AK, Saddler JN, Tschaplinski TJ, Tuskan GA, Wyman CE (2014) Lignin valorization: improving lignin processing in the biorefinery. Science 344:6185

Zha Y, Punt PJ (2013) Exometabolomics approaches in studying the application of lignocellulosic biomass as fermentation feedstock. Metabolites 3:119–143

Alvira P, Tomás-Pejó E, Ballesteros M, Negro MJ (2010) Pretreatment technologies for an efficient bioethanol production process based on enzymatic hydrolysis: a review. Bioresour Technol 101:4851–4861

Da Costa Lopes AM, João KG, Bogel-Łukasik E, Roseiro LB, Bogel-Łukasik R (2013) Pretreatment and fractionation of wheat straw using various ionic liquids. J Agric Food Chem 61(33):7874–7882

Galbe M, Zacchi G (2007) Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials for efficient bioethanol production. Adv Biochem Engin Biotechnol 108:41–65

Mäki-Arvela P, Anugwoma I, Virtanen P, Sjoholm R, Mikkola JP (2010) Dissolution of lignocellulosic materials and its constituents using ionic liquids—a review. Ind Crops Prod 32:175–201

Sathitsuksanoh N, George A, Zhang YHP (2012) New lignocellulose pretreatments using cellulose solvents: a review. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. doi:10.1002/jctb.3959

Zhang B, Shahbazi A (2011) Recent developments in pretreatment technologies for production of lignocellulosic biofuels. J Pet Environ Biotechnol 2(2):111

Zhu S, Yu P, Wang Q, Cheng B, Chen J, Wu Y (2013) Breaking the barriers of lignocellulosic ethanol production using ionic liquid technology. Bioresources 8(2):1510–1512

Bozell JJ (2010) An evolution from pretreatment to fractionation will enable successful development of the integrated biorefinery. Bioresources 5(3):1326–1327

Argyropoulos DS, Raleigh NC (2013) High value lignin derivatives, polymers, and copolymers and use thereof in thermoplastic, thermoset, composite, and carbon fiber applications. USPTO Patent: US 13771653. October 3

Kumar S, Singh SP, Mishra IM, Adhikari DK (2009) Recent advances in production of bioethanol from lignocellulosic biomass. Chem Eng Technol 32(4):517–526

Raganati F, Curth S, Götz P, Olivieri G, Marzocchella A (2012) Butanol production from lignocellulosic-based hexoses and pentoses by fermentation of Clostridium Acetobutylicum. Chem Eng Trans 27:91–96

Tashiro Y, Yoshida T, Noguchi T, Sonomoto K (2013) Recent advances and future prospects for increased butanol production by acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation. Eng Life Sci 00:1–14

Wyman CE (1994) Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: technology, economics, and opportunities. Bioresour Technol 50:3–16

Liu CZ, Feng Wang, Stiles AR, Guo C (2012) Ionic liquids for biofuel production: opportunities and challenges. Appl Energy 92:406–414

Brandt A, Gräsvik J, Halletta JP, Welton T (2013) Deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass with ionic liquids. Green Chem 15(3):550–583

Leskinen T, King AW, Kilpeläinen I, Argyropoulos DS (2013) Fractionation of lignocellulosic materials using ionic liquids: Part 2. Effect of particle size on the mechanisms of fractionation. Ind Eng Chem Res 52(11):3958–3966

Da Costa Lopes AM, João KG, Morais AR C, Bogel-Łukasik E, Bogel-Łukasik R (2013b) Ionic liquids as a tool for lignocellulosic biomass fractionation. Sustain Chem Process 1. doi:10.1186/2043-7129-1-3

Da Costa Lopes AM, Joao KG, Rubik DF, Bogel-Łukasik E, Duarte LC, Andreaus J, Bogel-Łukasik R (2013) Pre-treatment of lignocellulosic biomass using ionic liquids: wheat straw fractionation. Bioresour Technol 142:198–208

Magalhães da Silva SP, da Costa Lopes AM, Roseiro LB, Bogel-Lukasik R (2013) Novel pre-treatment and fractionation method for lignocellulosic biomass using ionic liquids. RSC Adv 3:16040–16050

George A, Brandt A, Tran K, Zahari SMS-NS, Klein-Marcuschamer D, Sun N, Sathitsuksanoh N, Shi J, Stavila V, Parthasarathi R, Singh S, Holmes BM, Welton T, Simmons BA, Hallett JP (2015) Design of low-cost ionic liquids for lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. Green Chem 17:1728–1734

Chen L, Sharifzadeh M, MacDowell N, Welton T, Shah N, Hallett JP (2014) Inexpensive ionic liquids: [HSO4]−-based solvent production at bulk scale. Green Chem 16(6):3098–3106

Da Costa Lopes AM, Bogel-Łukasik R (2015) Acidic ionic liquids as sustainable approach of cellulose and lignocellulosic biomass conversion without additional catalysts. Chem Sus Chem 8:947–965

Anugwom I, Eta V, Virtanen P, Maki-Arvela P, Hedenstrom M, Yibo M, Hummel M, Sixta H, Mikkola JP (2014) Towards optimal selective fractionation for Nordic woody biomass using novel amine–organic superbase derived switchable ionic liquids (SILs). Biomass Bioenergy 70:373–381

Anugwom I, Eta V, Virtanen P, Mki-Arvela P, Hedenstrçm M, Hummel M, Sixta H, Mikkola JP (2014) Switchable ionic liquids as delignification solvents for lignocellulosic materials. Chem Sus Chem 7:1170–1176

Groff D, George A, Sun N, Sathitsuksanoh N, Bokinsky G, Simmons BA, Holmes BM, Keasling JD (2013) Acid enhanced ionic liquid pretreatment of biomass. Green Chem 15:1264–1267

Lozano P, Bernal B, Recioa I, Belleville M-P (2012) A cyclic process for full enzymatic saccharification of pretreated cellulose with full recovery and reuse of the ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride. Green Chem 14:2631–2637

Sun N, Rahman M, Qin Y, Maxim ML, Rodríguez H, Rogers RD (2009) Complete dissolution and partial delignification of wood in the ionic liquid1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate. Green Chem 11:646–655

Ungurean M, Csanádi Z, Gubicza L, Péter F (2014) An integrated process of ionic liquid pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass with immobilised cellulase. Bioresources 9(4):6100–6116

Soudham VP, Gräsvik J, Alriksson B, Mikkola J-P, Jönsson LJ (2013) Enzymatic hydrolysis of Norway spruce and sugarcane bagasse after treatment with 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium formate. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 88(12):2209–2215

Su W (2012) A study of cellulose dissolution in ionic liquidwater brines. Umeå University. Available <http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:545389/FULLTEXT01.pdf>

Nunes E, Quilhó T, Pereira H (1999) Anatomy and chemical composition of Pinus pinea L. bark. Ann For Sci 56:479–484

Räisänen T, Athanassiadis D (2013) Basic chemical composition of the biomass components of pine, spruce and birch. <http://www.biofuelregion.se>

Valentín L, Kluczek-Turpeinen B, Willför S, Hemming J, Hatakka A, Steffen K, Tuomela M (2010) Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) bark composition and degradation by fungi: potential substrate for bioremediation. Bioresour Technol 101:2203–2209

Yang B, Dai Z, Ding SY, Wyman CE (2011) Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulosic biomass. Biofuels 2(4):421–450

Li C, Knierim B, Manisseri C, Arora R, Scheller HV, Auer M, Vogel KP, Simmons BA, Singh S (2010) Comparison of dilute acid and ionic liquid pretreatment of switchgrass: Biomass recalcitrance, delignification and enzymatic saccharification. Bioresour Technol 101(13):4900–4906

Lee SH, Doherty TV, Linhardt RJ, Dordick JS (2009) Ionic liquid-mediated selective extraction of lignin from wood leading to enhanced enzymatic cellulose hydrolysis. Biotechnol Bioeng 102(5):1368–1376

Rahikainen J, Mikander S, Marjamaa K, Tamminen T, Lappas A, Viikari L et al (2011) Inhibition of enzymatic hydrolysis by residual lignins from softwood–study of enzyme binding and inactivation on lignin-rich surface. Biotechnol Bioeng 08(12):2823–2834

Rahikainen J, Martin-Sampedro R, Heikkinen H, Rovio S, Marjamaa K, Tamminen T, Rojas OJ, Kruus K (2013) Inhibitory effect of lignin during cellulose bioconversion: the effect of lignin chemistry on non-productive enzyme adsorption. Bioresour Technol 133:270–278

Zhu L, O’Dwyer JP, Chang VS, Granda CB, Holtzapple MT (2008) Structural features affecting biomass enzymatic digestibility. Bioresour Technol 99:3817–3828

Singh S, Simmons BA, Vogel KP (2009) Visualization of biomass solubilization and cellulose regeneration during ionic liquid pretreatment of switchgrass. Biotechnol Bioeng 104:68–75

Tadesse H, Luque R (2011) Advances on biomass pretreatment using ionic liquids: an overview. Energy Environ Sci 4:3913–3929

Abu-Eishah SI (2011) Ionic liquids recycling for reuse. In: Handy S (ed) Ionic liquids-classes and properties: InTech

Lan Mai N, Ahn K, Koo Y-M (2014) Methods for recovery of ionic liquids—a review. Process Biochem 49:872–881

Vancov T, Alston A-S, Brown T, McIntosh S (2012) Use of ionic liquids in converting lignocellulosic material to biofuels. Renew Energy 45:1–6

Weerachanchai P, Lee JM (2014) Recyclability of an ionic liquid for biomass pretreatment. Bioresour Technol 169:336–343

Hou XD, Smith TJ, Li N, Zong MH (2012) Novel renewable ionic liquids as highly effective solvents for pretreatment of rice straw biomass by selective removal of lignin. Biotechnol Bioeng 109(10):2484–2493

Mou HY, Orblin E, Kruus K, Fardim P (2013) Topochemical pretreatment of wood biomass to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis of polysaccharides to sugars. Bioresour Technol 142:540–545

Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhang R, Liu G, Cheng G (2014) Understanding changes in cellulose crystalline structure of lignocellulosic biomass during ionic liquid pretreatment by XRD. Bioresour Technol 151:402–405

Samayam IP, Hanson BL, Langan P, Schall CA (2011) Ionic-liquid induced changes in cellulose structure associated with enhanced biomass hydrolysis. Biomacromolecules 12 (8):3091–3098

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, Crocker D (1998b) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP). Technical Report NREL/TP-510-42618. Golden, Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Sluiter A, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D (1998a) Determination of extractives in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP). Technical Report NREL/TP-510-42619. Golden, Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Pedersen M, Meyer AS (2010) Lignocellulose pretreatment severity – relating pH to biomatrix opening. New Biotechnol 27(6):739–750

Wang Y, Wei L, Li K, Ma Y, Ma N, Ding S, Wang L, Zhao D, Yan B, Wan W, Zhang Q, Wang X, Wang J, Li H (2014) Lignin dissolution in dialkylimidazolium-based ionic liquid-water mixtures. Bioresour Technol 170:499–505

Soudham VP, Brandberg T, Mikkola JP, Larsson C (2014) Detoxification of acid pretreated spruce hydrolysates with ferrous sulfate and hydrogen peroxide improves enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation. Bioresour Technol 66:559–565

Authors’ contributions

VPS is responsible for designing and performing all the experiments including chemical composition of biomass, pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentations, chemical analysis, and data analysis; also, the manuscript was prepared by him. DGR and IA were responsible for preparing the IL solvents. TB, CL, and J-PM wrote parts of the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Umeå University, Kempe Foundations and Bio4Energy program. This work is a part of activities of the Wallenberg Wood Science Center and the Johan Gadolin Process Chemistry Centre at Åbo Akademi University.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Tables S1–S5. Sugars released from the hydrolysis of lignocellulose materials. Sugars released from the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocelluloses non-treated and treated with either H2SO4 (205 °C for 10 min) or (S)IL solvents at (A) 120 °C for 90 min (B) 160 °C for 90 min and (C) 180 °C for 60 min. Sugars released from the acid pre-hydrolysis are also shown. AH is acid hydrolysate and EH is enzymatic hydrolysate

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Soudham, V.P., Raut, D.G., Anugwom, I. et al. Coupled enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanol fermentation: ionic liquid pretreatment for enhanced yields. Biotechnol Biofuels 8, 135 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-015-0310-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-015-0310-3