Abstract

The physical and chemical structure of activated carbon (AC) varies with the carbonization temperature, activation process and time. The texture and toughness of the starting raw material also determine the morphology of AC produced. The Brunauer-Emmet-Teller surface area (SBET) is small for AC produced at low temperatures but increases from 500 to 700 °C, and generally drops in activated carbons synthesized > 700 °C. Mild chemical activators and low activator concentrations tend to generate AC with high SBET compared to strong and concentrated oxidizing chemicals, acids and bases. Activated carbon from soft starting materials such as cereals and mushrooms have larger SBET approximately twice that of tough materials such as stem berks, shells and bones. The residual functional groups observed in AC vary widely with the starting material and tend to reduce under extreme carbonization temperatures and the use of highly concentrated chemical activators. Further, the adsorption capacity of AC shows dependency on the size of the adsorbate where large organic molecules such as methylene blue are highly adsorbed compared to relatively small adsorbates such as phenol and metal ions. Adsorption also varies with adsorbate concentration, temperature and other matrix parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human population growth accompanied by economic and industrial developments continuously demand clean and fresh water supplies. Manufacturing, mining and agriculture release pollutants with detrimental effects on man and the environment. Heavy metals in water have toxic effects resulting in death and chronic illness. Reports show a cancer risk of ~ 76% and ~ 15.7% was caused by cadmium and arsenic, respectively from the adsorption of the metals from the soil in paddy rice [1]. Most hazardous non-essential heavy metals and metalloids, for example, arsenic, lead, cadmium, and mercury have been reported in food crops and are deleterious in various respects [2, 3]. Oil exploration sites register the highest pollutants [4, 5]. There are also health hazards of fertilizers, pesticides, antibiotics and dyes from industrial discharge [6]. Therefore, it is crucial to find an environmentally benign approach to curb water pollution. Common water treatment techniques include; magnetic separation [7], flocculation [8], filtration [9], reverse osmosis [10] and adsorption [11, 12]. Physicochemical treatments that involve coagulation-flocculation processes were generally found to be unable to remove pharmaceuticals and personal care products [13].

Adsorption processes are generally cheap, easy to operate, and highly efficient. During an adsorption-based wastewater treatment process, organic and inorganic pollutants (adsorbates) are attracted to the outer and inner surfaces of the porous materials (adsorbents), through mass transfer and diffusion from the aqueous media to the active adsorbing sites of the adsorbents. The mechanisms are either chemisorption involving ionic interactions or physisorption such as Van der Waals and π–π interactions or both [14,15,16]. Several materials such as clays, zeolites and carbon have been used as adsorbents but the structure of the latter (carbon) can be predicted and tuned to meet specific adsorption needs where a target pollutant can be removed efficiently.

Carbon with four electrons to complete its octet gives it unique properties among which the ability to form multiple bonds with the saturation of electrons like in the case of the diamond where it is a non-conductor of electricity or a more interesting arrangement with unsaturation and hence free electrons that enable electrical conductivity in graphite and amorphous carbon. Perhaps the other unique feature is the ability of carbon atoms to bond with an irregular fashion in charcoal or a regular packing to form crystals, for instance, the graphitic form such as fullerenes first discovered by Kroto [17], graphene and carbon nanotubes first synthesized by Iijima [18] which can have open ends or one end capped with half fullerene (Fig. 1).

(a) Graphite made of layers of graphene; (b) Fullerene made of graphene layer joined end to end; (c) Multi-walled carbon nanotube with concentric hollow graphene rings; (d) Single-walled carbon nanotube with a half-fullerene endcap [19]

The hollow and enclosed nature of crystalline carbon has versatile applications in material storage, for instance, hydrogen [20]. Electric charge storage where carbon nanomaterial from plastic wastes was used to make supercapacitors has been reported [21]. Perhaps the most interesting is the amorphous form of carbon which despite the irregular arrangement tend to have carbon atoms stuck together with crevices and internal micropores in the structure where both organic and inorganic compounds in liquid and gas phase can be stored via physical and chemical linkages which is enhanced by the presence of other functional groups especially for activated carbon derived from biomass. Activated carbon has a large surface area and creates voids of varying pore volumes depending on the raw material carbonized. This is visible as dark spots in images from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 2). Microporosity of carbon has been utilized in water purification and the removal of organic compounds such as dye in wastewater from textile industries.

SEM image showing varying surface pore sizes (indicated by red dotted lines) in activated carbon produced from banana peels carbonized at: (a) 600 °C; (b) 700 °C [22]

Perhaps the most interesting is the existence of heteroatoms that remain after carbonization. These result from the action of heat or chemical interaction of chemical activators on functional groups of building parts of plants or animals. Heteroatoms enable chemisorption which not only enhances the adsorption capacity but also increase the range of adsorbates. It is against this background that we envisaged reviewing the correlation of the structural properties of activated carbon to the carbonization conditions and relating it to the nature of the starting raw material and the adsorption capacity.

Structural properties of activated carbon based on the source of carbonized material and conditions

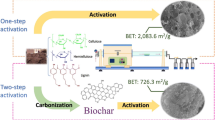

Surface properties of activated carbon such as surface area, pore size and pore volume are essential and an indication of the extent of heterogeneity of AC and give a clue of its internal structure [23], which highly depends on the method of activation and synthesis [24]. Synthesis of activated carbon involves two stages; first, carbonization which involves the thermal decomposition of raw materials under an inert atmosphere to remove functional groups containing heteroatoms resulting in the production of biochar. The second stage is activation which can be by physical reagents using selected gases such as steam and carbon dioxide or chemical activation where oxidizing and dehydrating chemicals are employed [25,26,27]. Activation increases the surface area of biochar which is usually below 300 m2/g after carbonization attributed to clogged pores by tarry materials [28, 29]. However, the extended time during activation at high temperatures tends to lower the yield of AC [30]. The decrease in yield at high temperatures is attributed to the secondary decomposition of biochar but it improves the quality of AC [31]. Nevertheless, chemical activation combines the activation and carbonization processes saving heat energy and hence low temperatures required. It however requires a cleaning process to flush the unreacted chemicals and undesired products [32, 33]. Commonly used chemical activators include ZnCl2, KOH, NaOH, H2SO4 and H3PO4. Chemical activation induces cyclization, dehydration and condensation reactions that promote pyrolytic decomposition and formation of cross-linkages which aid in the creation of both mesopores and micropores [34, 35].

This section summarizes how the structural properties of activated carbon such as surface area, pore size and volume, and residual functional groups present in AC relate to the raw material carbonized, the temperature of carbonization and the chemical activator used. Further, the dependence of the adsorption capacity on the nature of the adsorbate and SBET was also investigated.

Surface area of activated carbon from soft and hard raw materials

The surface area of activated carbon is highly dependent on the softness/hardness of the material to be carbonized (Table 1). Generally, tough materials such as stem barks, bone and shells yield activated carbon with small SBET compared to soft and tender raw materials such as leaves, cereals and soft plants such as mushrooms. This is evident from the relatively small SBET (316–989 m2/g)) for activated carbon derived for instance, from chicken bone (316 m2/g) [36],, black wattle bark (414 m2/g) [37], sugarcane bagasse (692 m2/g) [38] and chestnut oak shells (989 m2/g) [39] as compared to SBET > 1000 m2/g for activated carbon synthesized from rice husks, sorghum and Ganoderma lucidum [40,41,42] which is likely due to the ease for heat penetration that burns the soft materials uniformly (Fig. 3). It is also worth noting that solid lamps such as bones, stem barks and shells have a reduced surface area compared to grains like sorghum and rice husk pellets which might have contributed to the low SBET observed in AC of the latter and vice versa.

Variation of BET surface area with the nature of carbonized material; (a) Soft materials; (b) Tough materials. The data used to generate the graphs was obtained from the literature (Table 1)

It can be observed that irrespective of the raw material being carbonized, SBET decreased with increased temperature and it is relatively low when base activators are used (Table 1). There is no clear correlation between total pore volume and any of the carbonization conditions, however, the pore volume generally increases with an increase in the BET surface area.

Effect of temperature, activator and time of carbonization on total pore volume and surface area of activated carbon

The properties of activated carbon largely depend on the mode of activation and the carbonization temperature. Physical activation employs oxidizing gases like air, carbon dioxide and steam at higher temperatures that imparts pores on the surface of the carbonized material which increases the surface area and enhances the porosity [52]. On the other hand, chemical activation by acidic and basic activators or other oxidizing agents such as potassium permanganate dehydrate or oxidize the raw material of plant or animal origin thereby reducing the moisture content and also altering functional groups which would otherwise be difficult to eliminate during the heating. This leaves mostly the carbon content thus a further increase of the surface area. It is worth noting that activated carbon with small SBET is produced at both low concentrations of the activating agent and low temperature and SBET increases on an increase in temperature and activator concentration but to a certain limit. Extreme temperatures, long heating times and exceedingly higher proportions of the activator tend to reduce the SBET as observed from a study by Wang and group [51] (Fig. 4).

Dependency of BET surface area and total pore volume of activated carbon on: (a) Carbonization temperature; (b) Concentration of chemical activator; (c) Carbonization time. The data used to generate the curves was obtained from recent research findings [51]

The surface texture, pore shape and pore size also vary greatly with carbonization temperature and the concentration of activator used during production of AC. This can be observed of SEM images of AC synthesized from paulownia wood (Figs. 5 and 6).

SEM images of activated carbons prepared from paulownia wood chemically activated using different mass of phosphoric acid to wood powder ratios at 400 °C: (a) 1:1; (b) 2:1; (c) 3:1; (d) 4:1 [53].

It is worth to tell that physical activation significantly affects the structural properties of activated carbon. Higher surface area and larger total pore volume and pore sizes was observed in activated carbon synthesized by chemical activation using potassium hydroxide compared to the one prepared by two-activation process using carbon dioxide as the physical activator in addition to the base (1836 vs. 1628 m2/g, 1.126 vs. 0.999 cm3/g and 0.258 vs. 0.150 cm3/g for mesopores/ 0.805 vs. 0.648 cm3/g for micropores, respectively) [40].

SEM images of activated carbons prepared from paulownia wood carbonized at different temperatures: (a) 300 °C; (b) 400 °C; (c) 500 °C; (d) 600 °C [53].

Effect of carbonization conditions on residual functional groups present in activated carbon

Besides the large surface area and pores, the presence of residual functional groups enhances the adsorption capacity of activated carbon. Hydrogen and electronegative atoms are left after volatilization by heat, and chemical oxidation and other reactions by chemical activators on groups such as phenols, carboxylic acids, alcohols, amines etc. The presence of heteroatoms in activated carbon allows interactions such as electrostatic attractions of metals and hydrogen bonding with pharmaceuticals and other organic pollutants. Therefore, the presence of other atoms/functional groups in activated carbon is vital.

Carbonization conditions especially the temperature and the chemical activator determine the number and nature of functional groups present in activated carbon. The residual hydroxyl stretch is observed in the infrared spectra of almost all synthesized activated carbons except in one instance where a combination of zinc chloride and phosphoric acid were used as chemical activators [45]. This suggests a destructive effect of chemical activators on the functional groups present in the raw material before carbonization. The presence of residual heteroatoms is summarized in Fig. 7.

Residual function groups in activated carbon. The data used to generate the graphs was obtained from the literature (Table 1)

The number of heteroatoms present largely depends on the nature of the starting material, however, their presence in the carbonized material is reduced with an increase in temperature and the oxidizing potential of the activator (Table 1). High heats provide sufficient energy to break chemical bonds, a similar scenario caused by strong oxidizing agents. Nevertheless, the absence of a chemical activator [47] or the use of mild activators such as potassium silicate tends to leave many heteroatoms even at high carbonization temperatures [48]. Generally, heating biomass to carbonaceous materials and their surface activation eliminates the functional groups present in the raw material. However, activation does not alter much heteroatoms present as seen infrared spectra (Fig. 8) of rice husks and the formed char and activated carbon as reported by Yafei and Yuhong [40].

Dependency adsorption capacity of activated carbon on its morphology and the nature of adsorbates

Activated carbon is mostly used in water purification and other contaminated liquids to remove unwanted pollutants [25, 54]. Adsorption depends on the extent of porosity and the electrostatic interactions which indicates dependency on the nature of the adsorbates since they have varying functional groups and sizes that influence the interaction with the carbonaceous materials and the leaching process (desorption), respectively.

The adsorption capacity of activated carbon depends on the nature adsorbate and SBET of the AC (Table 2). For a similar class of compounds, it can be observed that metal ions are weakly adsorbed (< 50 mg/g) compared to organic compounds. In the reported research works, adsorption capacities of 35 mg/g and 33 mg/g of chromium(VI) and nickel(II) ions, respectively were achieved despite the large SBET of AC used [39, 48]. Structural properties; SBET and Vt play a great role in adsorption as observed from the exceedingly high adsorption capacity of methylene blue (935 mg/g) using AC with large SBET (1430 m2/g) [41] compared to 199 mg/g by AC with SBET 579 m2/g [47].

Further, it can also be observed that large molecules are highly adsorbed compared to small adsorbates. Similar to the poor adsorption of the relatively small metal ions, it can be seen that larger organic compounds are highly adsorbed by AC with SBET in the range 400–700 m2/g, for instance, methylene blue (199 mg/g) [47] compared to ≤ 119 mg/g for relatively smaller organic adsorbates for example, phenol, naphthalene and phenanthrene [37, 38, 45] (Fig. 9).

The adsorption behaviour of activated carbon is also highly dependent on the porosity of the material and the adsorbate concentration. At relatively low adsorbate concentration, activated carbon with large pore sizes/volume showed a higher edge to one with relatively small pore sizes and volume. Nevertheless, the performance of both materials was similar with the former having a slight edge which likely due to slow diffusion/leaching of the adsorbed material out of the AC with larger pore volume [40]. The increase in adsorption capacity with an increase in adsorbate concentration was also observed in work reported by Jinlong et al. however, poor adsorption of both methylene blue and ofloxacin was recorded with increasing temperature at low adsorbate concentrations (Fig. 10) [47]. On the contra, at higher adsorbate concentration, enhanced adsorption of ofloxacin was observed at low temperatures which suggests adsorbate-adsorbent interactions dependent on the nature of the adsorbate species since they are made of different chemical composition.

Effect of concentration and temperature on adsorption methylene blue (a) and ofloxacin (b) by fruit-shell activated carbon [47]

Conclusions

The carbonization conditions and nature of starting material determine the morphology of activated carbon. Soft materials tend to give AC with large SBET. Extremely high carbonization temperatures (> 700 °C) and strong chemical activators at high concentrations reduce SBET and also eliminate heteroatoms thereby reducing the residual function groups. For enhanced adsorption capacities of AC, soft materials should be carbonized at relatively low temperatures (< 600 °C) and vice versa. Large organic compounds are highly adsorbed compared to small adsorbates like metal ions. The porosity of carbon influences the diffusion and leaching of materials in and out, respectively. Adsorption performance of AC is also highly dependent on the adsorbate particles present in water, temperature and other physical parameters.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Mao C, Song Y, Chen L, Ji J, Li J, Yuan X, Yang Z, Ayoko GA, Frost RL, Theiss F. Human Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Paddy Rice based on transfer characteristics of Heavy metals from Soil to Rice. CATENA. 2019;175:339–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2018.12.029

Rai PK, Lee SS, Zhang M, Tsang YF, Kim K-H. Heavy metals in Food crops: Health risks, Fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ Int. 2019;125:365–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.067

Gall JE, Boyd RS, Rajakaruna N. Transfer of Heavy metals through terrestrial food webs: a review. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187:201.

Šimko P. Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic hydrocarbons in smoked meat products and Smoke Flavouring Food Additives. J Chromatogr B. 2002;770(1):3–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4347(01)00438-8

Tongo I, Ogbeide O, Ezemonye L. Human Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in smoked fish species from markets in Southern Nigeria. Toxicol Rep. 2017;4:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2016.12.006

Ahmad T, Danish M. Prospects of Banana Waste utilization in Wastewater Treatment: a review. J Environ Manage. 2018;206:330–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.10.061

Mansour F, Al-Hindi M, Yahfoufi R, Ayoub GM, Ahmad MN. The use of activated Carbon for the removal of pharmaceuticals from Aqueous solutions: a review. Rev Environ Sci Bio/Technology. 2018;17(1):109–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-017-9456-8

Bolisetty S, Peydayesh M, Mezzenga R. Sustainable Technologies for Water Purification from Heavy Metals: review and analysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48(2):463–87. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CS00493E

Teow YH, Mohammad AW. New Generation nanomaterials for Water Desalination: a review. Desalination. 2019;451:2–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.11.041

Yang Z, Zhou Y, Feng Z, Rui X, Zhang T, Zhang ZA. Review on reverse osmosis and nanofiltration membranes for Water Purification. Polym (Basel). 2019;11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11081252

Awad AM, Jalab R, Benamor A, Nasser MS, Ba-Abbad MM, El-Naas M, Mohammad AW. Adsorption of Organic pollutants by Nanomaterial-based adsorbents: an overview. J Mol Liq. 2020;301:112335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112335

Dotto GL, McKay G. Current scenario and challenges in Adsorption for Water Treatment. J Environ Chem Eng. 2020;8(4):103988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2020.103988

Bolong N, Ismail AF, Salim MR, Matsuura TA. Review of the effects of emerging contaminants in Wastewater and options for their removal. Desalination. 2009;239(1):229–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.03.020

Elwakeel KZ, Elgarahy AM, Khan ZA, Almughamisi MS, Al-Bogami AS. Perspectives regarding Metal/Mineral-Incorporating materials for Water Purification: with Special Focus on Cr(Vi) removal. Mater Adv. 2020;1(6):1546–74. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0MA00153H

Jahandar Lashaki M, Atkinson JD, Hashisho Z, Phillips JH, Anderson JE, Nichols M. The role of beaded activated Carbon’s pore size distribution on heel formation during cyclic Adsorption/Desorption of Organic vapors. J Hazard Mater. 2016;315:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.04.071

Rasoulpoor K, Poursattar Marjani A, Nozad E. Competitive chemisorption and physisorption processes of a Walnut Shell Based Semi-IPN Bio-composite Adsorbent for lead ion removal from Water: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Environ Technol Innov. 2020;20:101133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.101133

Kroto HW, Heath JR, O’Brien SC, Curl RF, Smalley RE. Buckminsterfullerene Nat. 1985;C60(6042):162–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/318162a0. 318.

Iijima S. Helical microtubules of Graphitic Carbon. Nature. 1991;354(6348):56–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/354056a0

Proctor JE, Armada DM. A. V. An Introduction to Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315368191

Wang H, Gao Q, Hu J. High Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Porous carbons prepared by using activated Carbon. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(20):7016–22. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja8083225

Kigozi M, Kasozi GN, Mohite SB, Zamisa S, Karpoormath R, Kirabira JB, Tebandeke E. Non-emission Hydrothermal Low-Temperature synthesis of Carbon nanomaterials from Poly (Ethylene Terephthalate) Plastic Waste for excellent Supercapacitor applications. Green Chem Lett Rev. 2023;16(1):2173025. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2023.2173025

Karume I, Bbumba S, Kigozi M, Nabatanzi A, Mukasa IZT, Yiga S. One-Pot removal of pharmaceuticals and Toxic Heavy Metals from Water using Xerogel-Immobilized Quartz/Banana peels-activated Carbon. Green Chem Lett Rev. 2023;16(1):2238726. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2023.2238726

Bhatia SK, Shethna HK. A modified pore filling isotherm with application in determination of pore size distributions. Langmuir. 1994;10(9):3230–43. https://doi.org/10.1021/la00021a055

Savova D, Apak E, Ekinci E, Yardim F, Petrov N, Budinova T, Razvigorova M, Minkova V. Biomass Conversion to Carbon adsorbents and Gas. Biomass Bioenergy. 2001;21(2):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0961-9534(01)00027-7

Wong S, Ngadi N, Inuwa IM, Hassan O. Recent advances in applications of activated Carbon from Biowaste for Wastewater Treatment: a short review. J Clean Prod. 2018;175:361–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.059

Ukanwa KS, Patchigolla K, Sakrabani R, Anthony E, Mandavgane S. A review of chemicals to produce activated Carbon from Agricultural Waste Biomass. Sustainability. 2019;11(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226204

Danish M, Ahmad TA, Review on. Utilization of Wood Biomass as a sustainable precursor for activated Carbon Production and Application. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;87:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.02.003

Rashidi NA, Yusup SA, Review on. Recent Technological Advancement in the activated Carbon Production from Oil Palm Wastes. Chem Eng J. 2017;314:277–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.11.059

Yahya MA, Al-Qodah Z, Ngah CWZ. Agricultural Bio-waste materials as potential sustainable precursors used for activated Carbon production: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;46:218–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.051

Ao W, Fu J, Mao X, Kang Q, Ran C, Liu Y, Zhang H, Gao Z, Li J, Liu G, et al. Microwave assisted Preparation of activated Carbon from Biomass: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;92:958–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.051

Reza MS, Islam SN, Afroze S, Abu Bakar MS, Sukri RS, Rahman S, Azad AK. Evaluation of the Bioenergy Potential of Invasive Pennisetum Purpureum through Pyrolysis and Thermogravimetric Analysis. Energy Ecol Environ. 2020;5(2):118–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-019-00139-0

Danish M, Hashim R, Ibrahim MNM, Sulaiman O. Effect of Acidic Activating agents on Surface Area and Surface Functional groups of activated carbons produced from Acacia Mangium Wood. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2013;104:418–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.06.003

Maciá-Agulló JA, Moore BC, Cazorla-Amorós D, Linares-Solano A. Activation of coal Tar Pitch Carbon fibres: physical activation vs. Chemical activation. Carbon N Y. 2004;42(7):1367–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2004.01.013

Heidari A, Younesi H, Rashidi A, Ghoreyshi A. Adsorptive removal of CO2 on highly Microporous activated Carbons prepared from Eucalyptus Camaldulensis Wood: Effect of Chemical activation. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2014;45(2):579–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2013.06.007

Budinova T, Ekinci E, Yardim F, Grimm A, Björnbom E, Minkova V, Goranova M. Characterization and application of activated Carbon produced by H3PO4 and water vapor activation. Fuel Process Technol. 2006;87(10):899–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2006.06.005

Oladipo AA, Ifebajo AO. Highly efficient magnetic chicken bone biochar for removal of tetracycline and fluorescent dye from Wastewater: two-stage Adsorber Analysis. J Environ Manage. 2018;209:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.030

Lütke SF, Igansi AV, Pegoraro L, Dotto GL, Pinto LAA, Cadaval TRS. Preparation of activated Carbon from Black Wattle Bark Waste and its application for Phenol Adsorption. J Environ Chem Eng. 2019;7(5):103396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103396

Eslami A, Borghei SM, Rashidi A, Takdastan A. Preparation of activated Carbon dots from Sugarcane Bagasse for Naphthalene removal from Aqueous solutions. Sep Sci Technol. 2018;53(16):2536–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2018.1462832

Niazi L, Lashanizadegan A, Sharififard H. Chestnut Oak shells activated Carbon: Preparation, characterization and application for cr (VI) removal from Dilute Aqueous solutions. J Clean Prod. 2018;185:554–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.026

Shen Y, Fu Y, KOH-Activated Rice. Husk Char via CO2 pyrolysis for Phenol Adsorption. Mater Today Energy. 2018;9:397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtener.2018.07.005

Wang H, Xie R, Zhang J, Zhao J. Preparation and characterization of distillers’ grain based activated Carbon as low cost Methylene Blue Adsorbent: Mass transfer and equilibrium modeling. Adv Powder Technol. 2018;29(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2017.09.027

Askari R, Mohammadi F, Moharrami A, Afshin S, Rashtbari Y, Vosoughi M, Dargahi A. Synthesis of activated Carbon from Cherry Tree Waste and its application in removing Cationic Red 14 dye from aqueous environments. Appl Water Sci. 2023;13(4):90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-023-01899-1

Razi MAM, Al-Gheethi A, Al-Qaini M, Yousef A. Efficiency of activated Carbon from Palm Kernel Shell for Treatment of Greywater. Arab J Basic Appl Sci. 2018;25(3):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765299.2018.1514142

Ibrahim WMHW, Amini MHM, Sulaiman NS, Kadir WRA. Powdered activated Carbon prepared from Leucaena Leucocephala Biomass for Cadmium Removal in Water purification process. Arab J Basic Appl Sci. 2019;26(1):30–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765299.2018.1533203

Awe AA, Opeolu BO, Fatoki OS, Ayanda OS, Jackson VA, Snyman R. Preparation and Characterisation of activated Carbon from Vitisvinifera Leaf Litter and its Adsorption performance for aqueous phenanthrene. Appl Biol Chem. 2020;63(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-020-00494-1

Mariana M, Mahidin M, Mulana F. and F. A. Utilization of Activated Carbon Prepared from Aceh Coffee Grounds as Bio-Sorbent for Treatment of Fertilizer Industrial Waste Water. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng, 2018, 358.

Wang J, Wang R, Ma J, Sun Y. Study on the application of Shell-activated Carbon for the adsorption of dyes and antibiotics. Water. 2022;14(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/w14223752

Kong J, Gu R, Yuan J, Liu W, Wu J, Fei Z, Yue Q. Adsorption Behavior of Ni(II) onto activated carbons from hide Waste and high-pressure steaming hide Waste. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;156:294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.03.017

Beltrame KK, Cazetta AL, de Souza PSC, Spessato L, Silva TL, Almeida VC. Adsorption of Caffeine on Mesoporous activated Carbon fibers prepared from Pineapple Plant leaves. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;147:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.08.034

Abbas AF, Ahmed MJ. Mesoporous activated Carbon from date stones (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) by one-step microwave assisted K2CO3 pyrolysis. J Water Process Eng. 2016;9:201–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2016.01.004

Wang B, Lan J, Bo C, Gong B, Ou J. Preparation of Ganoderma Lucidum Bran-based Biological activated Carbon for Dual-Functional Adsorption and detection of copper ions. Mater (Basel). 2023;16(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16020689

González-García P. Activated Carbon from Lignocellulosics precursors: a review of the synthesis methods, characterization techniques and applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;82:1393–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.04.117

Yorgun S, Yıldız D. Preparation and characterization of activated carbons from Paulownia Wood by Chemical activation with H3PO4. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2015;53:122–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2015.02.032

Rivera-Utrilla J, Sánchez-Polo M, Ferro-García MÁ, Prados-Joya G, Ocampo-Pérez R. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants and their removal from Water. Rev Chemosphere. 2013;93(7):1268–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.07.059

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge facilitation by Makerere University to access the literature used in writing this review.

Funding

The authors did not receive funding for writing this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.K, I.M and S.B wrote the main manuscript whereas S.T and M.N did a correlation analysis of the structural morphology of carbon to raw materials and dependency of adsorption capacity on adsorbate nature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Karume, I., Bbumba, S., Tewolde, S. et al. Impact of carbonization conditions and adsorbate nature on the performance of activated carbon in water treatment. BMC Chemistry 17, 162 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-023-01091-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-023-01091-1