Abstract

Background

Patients presenting with acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) of unknown aetiology, probably the earliest presentation of chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu), have been treated with oral prednisolone and doxycycline by physicians in Sri Lanka. This trial assessed the effectiveness of prednisolone and doxycycline based on eGFR changes at 6 months in patients with AIN of unknown aetiology.

Method

A randomized clinical trial with a 2 × 2 factorial design for patients presenting with AIN of unknown aetiology (n = 59) was enacted to compare treatments with; A-prednisolone, B-doxycycline, C-both treatments together, and D-neither. The primary outcome was a recovery of patients’ presenting renal function to eGFR categories: 61–90 ml/min/1.73m2 (complete remission– CR) to 31–60 ml/min/1.73m2 (partial remission– PR) and 0–30 ml/min/1.73m2 no remission (NR) by 6 months. A secondary outcome was progression-free survival (not reaching < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR), by 6–36 months. Analysis was by intention to treat.

Results

Seventy patients compatible with a clinical diagnosis of AIN were biopsied for eligibility; 59 AIN of unknown aetiology were enrolled, A = 15, B = 15, C = 14 and D = 15 randomly allocated to each group. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups. The number of patients with CR, PR and NR, respectively, by 6 months, in group A 3:8:2, group B 2:8:3 and group C 8:5:0 was compared with group D 8:6:1. There were no significant differences found between groups A vs. D (p = 0.2), B vs. D (p = 0.1) and C vs. D (p = 0.4).

In an exploratory analysis, progression-free survival in prednisolone-treated (A + C) arms was 0/29 (100%) in comparison to 25/30 (83%) in those not so treated (B + D) arms, and the log-rank test was p = 0.02, whereas no such difference found (p = 0.60) between doxycycline-treated (B + C) arms 27/29 (93%) vs those not so treated (A + D) arms 27/30 (90%).

Conclusion

Prednisolone and doxycycline were not beneficial for the earliest presentation of CKDu at 6 months. However, there is a potential benefit of prednisolone on the long-term outcome of CKDu. An adequately powered steroid trial using patients reaching < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR by 3 years, as an outcome is warranted for AIN of unknown aetiology.

Trial registration

Sri Lanka Clinical Trial Registry SLCTR/2014/007, Registered on the 31st of March 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Endemic chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu) which is prevalent in Sri Lanka and many other tropical countries rank amongst diabetes mellitus and essential hypertension in causing chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1,2,3,4,5]. This condition in Sri Lanka and Nicaragua shares many demographical and clinicopathological similarities that young male agricultural workers who perform strenuous labour in hot and humid working conditions are the worst affected [6, 7]. High levels of fluoride, calcium and magnesium carbonates in drinking water may be a causative factor in Sri Lanka as would exposure to infections with Leptospira and Hantavirus, along with agrochemicals, heavy metals, ochratoxins, cyanobacterial toxins and heat stress [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

CKDu is primarily a chronic interstitial disease which may have resulted from acute or subacute, low-grade recurrent interstitial nephritis [15,16,17]. Episodes of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) have been clearly demonstrated in the endemic populations of Sri Lanka and Nicaragua, demographics and pathology of these nephropathies are similar [18,19,20]. It is thought that immunomodulatory therapy is likely to decelerate the fibrotic process and hence the severity of irreversible kidney damage [21, 22].

After leptospirosis outbreaks in the dry zone of Sri Lanka in 2008 and 2011, leptospirosis was found to be endemic in a region where CKDu is also endemic [23]. Since a high proportion of CKDu patients are farmers, there is a possibility of exposure to urine and body fluids of Leptospira-infected animals during their farming activities [11]. AIN is the main pathology of renal leptospirosis which may present in a clinical form or cause subclinical infection [24, 25]. Considering leptospirosis as a possible cause for AIN of unknown aetiology, clinicians were tending to treat with doxycycline in addition to steroids, with no substantial evidence of its effectiveness.

The objectives of the current clinical trial were to assess the effectiveness of prednisolone or doxycycline treatment, compared to those without such treatment, for patients presenting with AIN of unknown aetiology from CKDu endemic regions of Sri Lanka. Our hypothesis was that these treatments improve a patients’ presenting renal function, either to a complete remission (CR) 61–90 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR or to a partial remission (PR) 60–31 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR by the sixth month of intervention.

Methods

Trial design and patients

This study is a single-centred prospective double-blinded randomized clinical trial. This was a factorial design where two treatments were combined for evaluation in a single study. The trial was conducted at the satellite renal clinics in the North Central Regions and the Dialysis and Transplant unit of Teaching Hospital Kandy, in Sri Lanka.

AIN of unknown aetiology, an acute manifestation of CKDu which is diagnosed after exclusion of known causes for kidney diseases by history, laboratory tests and histology. Adults without any known premorbid kidney diseases from CKDu endemic regions, particularly presenting with recent onset backache, feverishness, dysuria, arthralgia and or dyspepsia were screened by serum creatinine and urinalysis. A clinical history was taken to exclude premorbid renal diseases, and recent exposure to nephrotoxins, such as over-the-counter medications non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and proton pump inhibitors (PPI), and other treatments containing aristolochic acid. Aristolochic acid has been used in Ayurveda and traditional medicine in Sri Lanka as an ingredient of many herbal decoctions [26]. The doses of aristolochic acid preparations used in Sri Lanka are much lower than the doses associated with tubulo-interstitial nephropathy, according to Wijesinghe et al., 2016. However, the use of Aristolochic species for medicinal decoctions in Sri Lanka is considered a potential risk factor for AIN until the safe dose is defined.

Patients were diagnosed as probable AIN in the satellite renal clinics after ascertaining a few elevated serum creatinine measurements (> 116 males and > 98 µmol/L for females) and associated red cells, pus cells, and proteins in urine sediments, often within 2 weeks duration. Urine culture positives excluded. Renal ultrasonography (grayscale) was performed to confirm the presence of renal parenchymal disease, to exclude any obstructive kidney diseases, and to assess whether kidneys were not shrunken and of enough size (> 9 cm bipolar length) for biopsy. The normal sizes of kidneys for healthy individuals of CKDu endemic regions in Sri Lanka are 9.83 (1.49) cm for males and 9.46 (1.63) cm for females [27]. If consent given for biopsy and further treatment by patients, transferred to the tertiary care nephrology unit in Kandy.

Renal biopsies were examined with routine and special stains and direct immunofluorescence staining to detect immune complexes of IgG, A, and M, and complement. AIN was confirmed if there was interstitial inflammation and wide-spread tubulitis away from areas of interstitial and glomerular fibrosis, and tubular atrophy (Fig. 1). In addition, immune complex-mediated glomerular diseases, and other identifiable primary or secondary renal pathologies were excluded from histological evidence.

MAT test with a fourfold or greater rise 2 weeks apart samples have been using to diagnose cases of leptospirosis in Sri Lanka. Besides, a single reading of > 1/400 titre is supportive in clinically suspected cases when the second sample is not feasible. A titre of 1/100 or 1/200 is considered a probable case or a past infection in leptospirosis endemic regions, according to Haake and Levett et al., 2014. Cases of leptospirosis are diagnosed based on the MAT test when other serological tests and PCR amplification are not available for routine practice in low socioeconomical setups in Sri Lanka.

Biopsy-confirmed AIN cases of unknown aetiology were randomized and allocated for treatments. Serial creatinine and urinalysis were performed according to the study protocol.

Interventions and outcomes

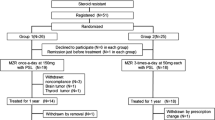

A factorial randomization was done to assign patients to one of four treatment arms (Fig. 2): arm “A” 15 patients (oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/body weight as a single daily dose and a placebo for 1 month, tapered over 5 to 12 weeks); arm “B” 15 patients (oral doxycycline 100 mg twice day and a placebo for 1 month); arm “C” 14 patients (a combination of prednisolone and doxycycline treatments); control arm “D” 15 patients (two placebos for a period of 1 month). The treatments were commenced for all groups with a median (IQR) 20 (17–34) days after onset of symptoms.

The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the CKD-EPI creatinine Eq. (2009). Renal function was graded based on estimated GFR (eGFR) categories (ml/min/1.75 m2): stage 1 > 90, stage –2 60–89, stage –3 30–59 (stage –3a 45–59, stage –3b 30–44), and ≥ stage –4 or < 30 eGFR.

The primary outcome was a recovery of patients’ presenting renal function to eGFR categories: 61–90 ml/min/1.73m2 (complete remission– CR), to 31–60 ml/min/1.73m2 (partial remission– PR) and 0–30 ml/min/1.73m2 no remission (NR) by 6 months. A secondary outcome was progression-free survival (patient not reaching < 30 eGFR), between 6 and 36 months after treatments. Other secondary outcomes were remission of proteinuria by the end of 6 months of treatment and requiring renal replacement therapy (RRTs) from baseline to 36 months.

Randomization and blinding

This is a pragmatic clinical trial conducted in the routine clinical setup. Biopsy-confirmed AIN cases of unknown aetiology were reviewed at the nephrology clinic in Kandy with their biopsy reports and explained about the clinical trial to the participants, by one of the two medical officers who were responsible for randomization and allocation of treatments. Those patients who consented for the trial were randomly allocated for treatments. The pharmacist and these two medical officers were not blinded for allocations. These staff members were not involved either in outcome evaluation or data analysis. They maintained separate trial data entry records of patients under their custody for review and re-evaluation of treatment compliance.

At the same time, trial participants and outcome adjudicators of the study had no access to trial records, thereby neither the patients nor the researchers knew who was getting which type of treatment. Furthermore, this was an individually randomized trial in which participants were randomly allocated over time and individually followed up amongst other routine clinic patients, limiting access to compare treatments. However, allocated medications were not concealed according to a double dummy technique.

Implementation

Biopsy proved 59 cases with AIN of unknown aetiology were eligible for the trial from 70 clinically suspected cases. Eleven cases were excluded after biopsy due to eight insufficient kidney tissues for reporting, one normal kidney tissue and two glomerulonephritis. Patients were followed-up monthly at the outpatient clinic until the completion of their allocated 3 months treatments. Prednisolone was discontinued due to gastric side effects in 2 patients (group A), and 3 others (2 from group B and 1 from group C) were lost to follow-up after treatment allocation. At the end of 6 months, 54 patients (92%) completed the allocated treatments, and at the end of 36 months, 45 patients (76%) had completed their allocated treatments and were retained for follow-up of outcome (Fig. 2).

Sample size of 50 cases for each arm was calculated on the assumptions of α = 0.05; power = 0.8, and 20% effect size (to achieve a 20% reduction from 144 (± 52) µmol/L mean serum creatinine). This mean creatinine value was calculated when designing the study, from the serum creatinine values of diagnosed AIN patients in the endemic regions, recorded in the biopsy request forms. We added about 15% loss to follow-up in a trial, for a sample size of 230. However, the broad inclusion criteria of the study failed to bring the required sample size and a meaningful effect to this study at 6 months of assessment. Based on the factorial design, prednisolone-treated patients (arms A + C) and no prednisolone-treated (arms B + D) were merged for an exploratory analysis to assess the outcome by 6–36 months from recruitment which was not prespecified (Fig. 2).

Statistical analysis

Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. Kruskal–Wallis’s test and Mann–Whitney’s test were used to compare the continuous variables. Continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile range (IQR). Survival analyses were performed with Kaplan–Meier curves and the group differences were estimated from the log-rank test. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistics were calculated using IBM SPSS version 20.

Results

Baseline characteristics namely, age, sex, eGFR, proteinuria, MAT titre, and rest of blood and urinary inflammatory markers of all four treatment arms were similar (Table 1). Treatments were commenced for all groups at 20 (17–34) median (IQR) days after the onset of symptoms. In the primary analysis, the number of patients with complete (CR), partial (PR) and no (NR) remission of renal function by 6 months, respectively, in group A 3:8:2, group B 2:8:3 and group C 8:5:0 was compared with group D 8:5:2. There were no significant differences found between groups A vs D (p = 0.2), B vs D (p = 0.1) and C vs D (p = 0.4).

In the exploratory analysis, progression-free survival (patients not reaching < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR) of prednisone-treated (A + C arms) patients at 36 months was 100% while 83% for no prednisolone-treated patients (B + D arms). The log-rank test provided a p-value of 0.02 indicating that the difference in survival between those treatment arms was statistically significant. In contrast, progression-free survival of doxycycline-treated (B + C arms) and no-doxycycline-treated (A + D arms) was 27/29 (93%) and 27/30 (90%), respectively, the overall difference between the survival curves over 36 months was not significant (p = 0.62). The Kaplan Meier survival plots for exploratory analysis are depicted in Fig. 3a and b.

When changes in GFR from baseline to 6 months were adjusted for baseline GFR, there was no significant difference found in groups A vs. D (p = 0.87), B vs. D (p = 0.26) and C vs. D (p = 0.45).

One patient in the no prednisolone-treated (B + D arms) required renal replacement therapy by the 3rd month of treatment and later underwent a kidney transplant. Proteinuria was observed only in less than 30% of AIN patients in groups at baseline. It declined over a period of 6 months from ≥ 1 + to nil: 20% of cases in group A, 25% in group B, 8% in group C and 15% in group D. Decline of proteinuria in the number of cases as a percentage between groups was not significant (p = 0.7). Moreover, an exploratory analysis for the primary outcome was done using patients' renal function recovery to > 61 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR, a pairwise comparison done with log-rank test (Fig. 3c). In a subgroup analysis, there were five cases that progressed to > stage 4 CKD at 3 years without receiving prednisolone as a treatment option. Their baseline eGFR were also in the lower range such as 31, 42, 33, 16 and 30 ml/min/1.73m2. In contrast, there were three cases with baseline eGFR < 30 ml/min/m2 who received a course of prednisolone as an intervention. The eGFR of these three cases at 3 years improved and remained high as 50, 37 and 53 ml/min/1.73m2.

Discussion

In this pragmatic clinical trial, prednisolone or doxycycline did not significantly improve renal function, 6 months after the commencement of treatment. A comprehensive understanding of the natural history of a disease is a prerequisite for designing, implementing and interpreting interventional studies. It was challenging to decide on study endpoints (development of CKD, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), renal replacement therapy (RRT) or death), duration of the study and biomarkers or surrogate end points (serum creatinine, eGFR, proteinuria) as this was the first prospective clinical trial on AIN of unknown aetiology with limited information on the natural history of the disease [28].

According to the study results, by 6 months, 55% (30/54) of trial participants have reached < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR, compatible with a CKD. Thus, statistically, it is a good trial outcome with a high event rate to assess interventions of CKDu progression. The event rates as ESRD, RRTs and death were extremely low (1/59) even at the end of 3 years. Considering the slow progression of CKDu, reaching < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 (stage 4 CKD) by 36 months was considered as a secondary outcome in this trial. The event rate for reaching < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR in the no prednisolone-treated patients was 5/30 (17%) by the end of 36 months. According to the subgroup analysis, steroids are beneficial even for cases with low eGFR (< stage 4 CKD) at baseline. Also, CKDu being a primary tubulointerstitial disease, a substantial proteinuria is not a feature of early disease, hence, may not be an appropriate surrogate end point for an interventional clinical trial. A tubular marker (biomarkers of tubular injury) is an optional surrogate for proteinuria [29,30,31].

Steroid treatment is recommended to be commenced early, at least within 7 days from initial injury for better outcomes. Nevertheless, treatments in this trial were commenced at 20 (17–34) median (IQR) days after the onset of symptoms. Until substantial knowledge is available on the time and sources of exposure and detection of suspected toxin(s) in human tissues, it is difficult to target the initial injury. According to this study, the progression in prednisolone-treated patients (none reached < 30 GFR) was relatively slower than not so treated patients (17% reached < 30GFR). Of AIN patients of Nicaragua who were followed up for 90 days after the acute onset of decline in renal function, only 21/247 (8.5%) had progressed to CKD without specific interventions [19]. In contrast, the incident stage 3 CKD at 6 months was 55% in AIN patients in our study. The significant difference in the incidence of CKD beyond months between the two acute nephropathies suggests two different etiologies. However, it is a comparison of two study groups with two different inclusion criteria.

Conclusions

This RCT did not significantly improve the renal function of patients with AIN of unknown aetiology, up to 2 years of follow-up as designed. In the exploratory analysis, there was a slower progression to CKD stage 4 in prednisolone-treated groups. Leptospirosis was accorded as a possible cause for this AIN and adding doxycycline did not have any favourable effect on the outcome. In conclusion, empirical steroid therapy practised by physicians on AIN of unknown aetiology is a potential treatment to delay the progression of CKDu. An adequately powered steroid trial using patients reaching < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR by 3 years, as an outcome is warranted for AIN of unknown aetiology, in addition to surveillance for early detection and interventions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIN:

-

Acute interstitial nephritis

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CKDu:

-

Chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology

- CR:

-

Complete remission

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NR:

-

No remission

- PR:

-

Partial remission

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

References

Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. The Lancet. 2013;382(9888):260–72.

Soderland P, Lovekar S, Weiner DE, Brooks DR, Kaufman JS. Chronic kidney disease associated with environmental toxins and exposures. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(3):254–64.

Jayasumana C. Chronic interstitial nephritis in agricultural communities (CINAC) in Sri Lanka. InSeminars in Nephrology. 2019;39(No. 3):278-83. WB Saunders. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2019.02.006.

Gifford FJ, Gifford RM, Eddleston M, Dhaun N. Endemic nephropathy around the world. Kidney international reports. 2017;2(2):282–92.

Correa-Rotter R. Mesoamerican nephropathy or chronic kidney disease of unknown origin. InChronic kidney disease in disadvantaged populations. 2017:221-228. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804311-0.00022-4.

Lunyera J, Mohottige D, Von Isenburg M, Jeuland M, Patel UD, Stanifer JW. CKD of uncertain etiology: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(3):379–85.

Wijkström J, Jayasumana C, Dassanayake R, et al. Morphological and clinical findings in Sri Lankan patients with chronic kidney disease of unknown cause (CKDu): Similarities and differences with Mesoamerican Nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3): e0193056.

Dissanayake CB, Chandrajith R. Groundwater fluoride as a geochemical marker in the etiology of chronic kidney disease of unknown origin in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Journal of Science. 2017;46(2). http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v46i2.7425.

Dharma-Wardana MW, Amarasiri SL, Dharmawardene N, Panabokke CR. Chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology and groundwater ionicity: study based on Sri Lanka. Environ Geochem Health. 2015;37(2):221–31.

Murray KO, Fischer RS, Chavarria D, Duttmann C, Garcia MN, Gorchakov R, et al. Mesoamerican nephropathy: a neglected tropical disease with an infectious etiology? Elsevier; 2015.

Gamage CD, Sarathkumara YD. Chronic kidney disease of uncertain etiology in Sri Lanka: Are leptospirosis and Hantavirus infection likely causes? Med Hypotheses. 2016;91:16–9.

Yang CW. Leptospirosis renal disease: emerging culprit of chronic kidney disease unknown etiology. Nephron. 2018;138(2):129–36.

Wimalawansa SJ, Dissanayake CB. Factors affecting the environmentally induced, chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology in dry zonal regions in tropical countries—Novel findings. Environments. 2020;7(1):2.

Nanayakkara I, Dissanayake RK, Nanayakkara S. The presence of dehydration in paddy farmers in an area with chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology. Nephrology. 2020;25(2):156–62.

Nanayakkara S, Komiya T, Ratnatunga N, Senevirathna ST, Harada KH, Hitomi T, Gobe G, Muso E, Abeysekera T, Koizumi A. Tubulointerstitial damage as the major pathological lesion in endemic chronic kidney disease among farmers in North Central Province of Sri Lanka. Environ Health Prev Med. 2012;17(3):213–21.

Wijetunge S, Ratnatunga NV, Abeysekera DT, Wazil AW, Selvarajah M, Ratnatunga CN. Retrospective analysis of renal histology in asymptomatic patients with probable chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Medical Journal. 2013 Dec 28;58(4).

Wijkström J, González-Quiroz M, Hernandez M, Trujillo Z, Hultenby K, Ring A, Söderberg M, Aragón A, Elinder CG, Wernerson A. Renal morphology, clinical findings, and progression rate in Mesoamerican nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(5):626–36.

Badurdeen Z, Nanayakkara N, Ratnatunga NV, Wazil AW, Abeysekera TD, Rajakrishna PN, et al. chronic kidney disease of uncertain etiology in Sri Lanka is a possible sequel of interstitial nephritis! Clinical nephrology. 2016;86(7):106.

Fischer RS, Mandayam S, Chavarria D, Vangala C, Nolan MS, Garcia LL, et al. Clinical evidence of acute Mesoamerican nephropathy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(4):1247–56.

Fischer RS, Vangala C, Truong L, Mandayam S, Chavarria D, Llanes OMG, et al. Early detection of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in the genesis of Mesoamerican nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2018;93(3):681–90.

Joyce E, Glasner P, Ranganathan S, Swiatecka-Urban A. Tubulointerstitial nephritis: diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(4):577–87.

Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis–a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82(3):149.

Agampodi SB, Dahanayaka NJ, Bandaranayaka AK, Perera M, Priyankara S, Weerawansa P, Matthias MA, Vinetz JM. Regional differences of leptospirosis in Sri Lanka: observations from a flood-associated outbreak in 2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(1): e2626.

Andrade L, de Francesco Daher E, Seguro AC. Leptospiral nephropathy. InSeminars in nephrology. 2008;28(No. 4):383-94. WB Saunders. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.04.008.

Aslan O. Leptospirosis; Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention: A Review. Microbiology Research Journal International. 2016;25:1–5.

Wijesinghe W, Pilapitiya S, Hettiarchchi P, Wijerathne B, Siribaddana S. Regulation of herbal medicine use based on speculation? A case from Sri Lanka. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;7(2):269–71.

Nadeeshani S, Dassanayake R, Kodithuwakku U. Ultrasonic Assessment of Kidney Length in a Sri Lankan Farming Population. Anuradhapura Med J. 2015;9(2Supp):S07. http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/amj.v9i2Supp.7556.

Jewell NP. Natural history of diseases: statistical designs and issues. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100(4):353–61.

Parikh CR, Moledina DG, Coca SG, Thiessen-Philbrook HR, Garg AX. Application of new acute kidney injury biomarkers in human randomized controlled trials. Kidney Int. 2016;89(6):1372–9.

Leaf DE, Waikar SS. Endpoints for clinical trials in acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(1):108–16.

Badurdeen Z, Alli-Shaik A, Ratnatunga NV, Abeysekera TD, Wijetunge S, Hemage RK, Fernando BN, Hettiarachchi TW, Gunaratne J, Nanayakkara N. Serum TGF-β1 and Creatinine for early diagnosis of CKDu phenotypes. Kidney International Reports. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2022.11.004.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the staff of the Nephrology and Renal Transplant unit, Teaching hospital, Kandy, and staff of renal sentinel clinics in the North Central region of Sri Lanka. We thank H.M.N.D. Herat, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Peradeniya, for the preparation of histological slides.

Funding

This trial was carried out under a routine clinical setup using Ministry of Health resources in Sri Lanka. Renal histology was carried out free of charge at the Department of Pathology, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. There were no funds allocated for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NN, TA, AWMW, PNR and JT were responsible for the initiation and development of the trial. NR reported renal biopsies. NN, PNR and JT are involved in the eligibility determination process. DDW, NR, and APDA monitored treatments and adverse events. RK, HA and ZB performed the statistical analysis. ZB developed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review committee of the Faculty of Medicine University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (2012/EC/54 dated 15/11/2012). All aspects of the trial were thoroughly explained to each participant and written informed consent was taken from all the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Badurdeen, Z., Ratnatunga, N., Abeysekera, T. et al. Randomized control trial of prednisolone and doxycycline in patients with acute interstitial nephritis of unknown aetiology. Trials 24, 11 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-07056-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-07056-4