Abstract

Background

There is a growing number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating interventions to prevent or treat delirium in the intensive care unit (ICU). Efforts to improve the conduct of delirium RCTs are underway, but none address issues related to statistical analysis. The purpose of this review is to evaluate heterogeneity in the design and analysis of delirium outcomes and advance methodological recommendations for delirium RCTs in the ICU.

Methods

Relevant databases, including PubMed and Embase, were searched with no restrictions on language or publication date; the search was conducted on July 8, 2019. RCTs conducted on adult ICU patients with delirium as the primary outcome were included where trial results were available. Data on frequency and duration of delirium assessments, delirium outcome definitions, and statistical methods were independently extracted in duplicate. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020141204).

Results

Among 65 eligible RCTs, 44 (68%) targeted the prevention of delirium. The duration of follow-up varied, with 31 (48%) RCTs having ≤7 days of follow-up, and only 24 (37%) conducting delirium assessments after ICU discharge. The incidence of delirium was the most common outcome (50 RCTs, 77%) for which 8 unique statistical methods were applied. The most common method, applied to 51 of 56 (91%) delirium incidence outcomes, was the two-sample test comparing the proportion of patients who ever experienced delirium. In the presence of censoring of patients at ICU discharge or death, this test may be misleading. The impact of censoring was also not considered in most analyses of the duration of delirium, as evaluated in 24 RCTs, with 21 (88%) delirium duration outcomes analyzed using a non-parametric test or two-sample t test. Composite outcomes (e.g., rank-based delirium- and coma-free days), used in 11 (17%) RCTs, seldom explicitly defined how ICU discharge, and death were incorporated into the definition and were analyzed using non-parametric tests (11 of 13 (85%) composite outcomes).

Conclusions

To improve delirium RCTs, outcomes should be explicitly defined. To account for censoring due to ICU discharge or death, survival analysis methods should be considered for delirium incidence and duration outcomes; non-parametric tests are recommended for rank-based delirium composite outcomes.

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42020141204. Registration date: 7/3/2019.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Delirium is a clinical syndrome in which patients have fluctuating impairments in attention and cognition [1]. This syndrome is highly prevalent among patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), with prevalence ranging from 50 to 80% [2, 3]. Delirium is associated with longer durations of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay, as well as increased risk of mortality [4]. Moreover, delirium is associated with long-term cognitive impairments [5, 6].

The number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating interventions to prevent or treat delirium in ICU patients has been increasing. There are ongoing efforts to establish standards for conducting such RCTs [7, 8]. Moreover, there are efforts to establish a core set of outcomes and associated measurement instruments for delirium RCTs in the ICU (https://deliriumnetwork.org/measurement/#measurement-resources, [9]) given important heterogeneity in these areas among existing RCTs [10].

The development of a core set of outcomes and measurement instruments are key steps towards improving comparability and harmonization across delirium RCTs. As highlighted by an international interprofessional panel [8], improving the conduct of delirium RCTs also requires evaluating heterogeneity in the statistical methods applied to delirium outcomes. Standardization of statistical methods will allow for improved comparison of the effect of interventions while appropriately accounting for key features of RCT design and patient population [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Hence, to advance the understanding of RCT design and statistical analysis of delirium outcomes and to assist with advancing methodologic recommendations, we undertook a systematic review of published delirium RCTs and provide related recommendations for the field.

Methods

This systematic review was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01AG061384), registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020141204) and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guideline ([17], Additional File Section 1).

Search strategy and selection criteria

An experienced medical librarian participated in designing the literature search strategy, which was peer-reviewed by another medical librarian prior to use. We searched the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search strategy was designed around the following key search terms: critical illness, delirium, and randomized trial (Additional File Section 2). There were no restrictions on language or publication date. The search was conducted on July 8, 2019.

The title and abstract of identified citations were independently screened, in duplicate, followed by independent, duplicate screening of the full text of the citations by trained research staff. The first author (EC) adjudicated discrepancies between these reviewers. Citations were included if they were the primary publication of a RCT of any intervention(s) (with any type of control group) individually randomized to patients treated in an ICU, with the primary outcome being delirium evaluated using a validated screening instrument ([18], Additional File Section 3) or diagnostic criteria [1]. In addition, we conducted hand searches of references from eligible citations, of three recent systematic reviews [19,20,21], and the Network for Investigating Delirium: Unifying Scientists (NIDUS) registry of delirium studies (https://deliriumnetwork.org/delirium-research-hub/).

Data extraction and quality assessment

The final data elements for extraction, and associated REDCap database, were derived after three rounds of iterative pilot testing. Data elements were extracted independently, in duplicate, with discrepancies resolved via consensus among the data extractors. Key RCT characteristics were extracted, including trial type (prevention only, treatment only, or both prevention and treatment), sample size, funding source, country, patient population, ICU type, and patient characteristics. Data on the delirium screening or diagnostic instrument, delirium assessment frequency, and duration of assessment were extracted. Delirium outcomes, a priori classified into four categories (Additional File Section 4) were recorded, as was outcome type (primary, secondary, or reported but not named as a primary or secondary outcome), and the statistical method(s) applied (Additional File Section 5). Similar data were collected for patient mortality and ICU length of stay. We recorded whether an analysis of the primary delirium outcome included adjustment for baseline variables, regardless of whether this analysis was the primary analysis or a secondary analysis. Study results for all delirium outcomes, mortality, and ICU length of stay were reported. The risk of bias was independently assessed by two raters, using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [22]. Study team members with training in epidemiology (MDH, DN, MOH) or biostatistics (XL, EC) extracted all data elements related to delirium outcome definition(s) and statistical analysis methods, in addition to completing the risk of bias assessment.

Data synthesis and analysis

The data were evaluated to identify potential outliers and missing values. All missing values were reviewed by study team members (MK, NA, and EC) and resolved when possible using a full-text review or contacting corresponding authors. Delirium outcomes and statistical methods were categorized by two biostatisticians with masters or doctoral training in biostatistics (EC and XL). Summary statistics of extracted data were computed for all studies and by trial type. In addition, recognizing key differences in surgery (cardiac and general surgery) and critically ill patients, i.e., mechanically ventilated, acute respiratory failure, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (MV, ARF, ARDS) patients, the statistical methods applied to delirium outcomes were summarized separately for RCTs conducted among surgery (cardiac and general surgery) vs. critically ill patients.

Results

Study characteristics

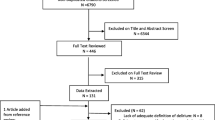

The comprehensive search strategy identified 15,242 citations. After removing duplicates, we reviewed the title and abstract of 11,805 citations and subsequently completed the full-text review of 808 citations. We identified 65 delirium RCTs, published between 2003 and 2019 (quartiles: 2003, 2016, 2017), that met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Of these, 44 (68%), 12 (18%), and 9 (14%) focused on delirium prevention only, treatment only, or both prevention and treatment, respectively (Table 1). The majority of the 65 RCTs were two-arm trials (a single intervention with the control group, n= 54, 83%) with 9 (14%) multi-arm and 2 (3%) factorial trials. The RCTs, including 12 foreign language papers (9 Chinese, 1 Italian, 1 Persian, and 1 Turkish), were conducted predominantly in the USA (n=16, 25%), China (12, 18%), and Iran (8, 12%), with only 20 (31%) reporting government-funding. Two members of the study team members (XL and NA) who were native speakers reviewed the Chinese and Persian articles. We reached out to bilingual collaborators who have expertise in delirium/research to help with the Italian and Turkish articles. The three most common patient populations were cardiac surgery (22, 34%), surgery (19, 29%), and ARF (17, 26%) patients. Among the 65 RCTs, the median (interquartile range) of the average patient age was 62 (59, 69) years old, and the median proportion of males was 62% (53%, 72%).

Literature Search Flow Chart. *We hand searched all the references of the eligible articles, the NIDUS bibliography (https://deliriumnetwork.org/delirium-research-hub/), and articles from relevant systematic reviews [19,20,21] and compared to the deduplicated articles from the electronic database search

Delirium assessments

The majority of RCTs (42, 65%) used the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) to assess delirium (Table 2). Assessments occurred once, twice, and more than twice per day in 23 (35%), 28 (43%), and 11 (17%) of eligible RCTs, respectively. The maximum duration for which delirium was assessed (i.e., the duration of follow-up) and was highly variable, with 3 days being the most common duration, used in 13 (20%) RCTs. Delirium was assessed for a maximum of ≤7 days in 31 (48%) RCTs, with 8 (12%) RCTs assessing delirium until ICU discharge. Delirium assessments were conducted only during the patient’s ICU stay for 41 (63%) RCTs, with a greater proportion of trials conducted among critically ill patients compared to surgery patients terminating delirium assessments at ICU discharge (14 of 17, 82% vs. 21 of 41, 51%, respectively). A single RCT reported a change in the frequency of delirium assessments following ICU discharge (twice daily during the ICU stay to daily while in the ward) [23].

Risk of bias

Of the 65 RCTs, 14 (22%) had a high risk of bias for at least one of the 5 categories that were evaluated. High risk of bias for the 5 categories are presented in Additional File Figure 1 and Additional File Table 2, with highlights herein: 7 (11%) RCTs were categorized as high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and 5 (8%) for incomplete outcome data with respect to the primary delirium outcome.

Delirium outcomes

Of the 65 RCTs, 61 (94%) reported a single primary delirium outcome and 4 reported delirium as a co-primary outcome. In addition, 29 (45%) RCTs reported a delirium-related outcome as a secondary outcome; with 20 and 8 reporting 1 or 2 secondary delirium outcomes, respectively. In the sections below, we report on the use of the four categories of delirium outcomes: delirium incidence, delirium composite outcome, delirium duration, and delirium severity, as well as the statistical methods applied to each outcome.

Delirium incidence outcome

There were a total of 56 delirium incidence outcomes reported by 50 (77%) of the 65 trials; 42 (65%), 6 (9%), and 2 (3%) RCTs reported only a primary, both a primary and secondary, or only a secondary delirium incidence outcome, respectively. In 5 RCTs (8%), delirium incidence was evaluated at multiple time points (e.g., 14 and 28 days) within the same trial. We identified two definitions of delirium incidence, whether the patient ever met the criteria for delirium during follow-up and the presence/absence of delirium on each day during the follow-up.

The 56 primary or secondary delirium incidence outcomes were evaluated using 8 unique statistical methods (Table 3). The variation in statistical methods applied to delirium incidence outcomes was similar when comparing RCTs conducted among surgery vs. critically ill patients (6 unique statistical methods, respectively; Additional File Table 4). The most common statistical method, applied to 51 (91%) of 56 outcomes, defined a binary indicator for delirium and used a two-sample test for proportions (e.g., chi-square test or logistic regression) to compare delirium incidence across interventions.

As an alternative, the time to first positive delirium assessment was identified and the hazard of delirium was compared using standard and competing risk survival analysis for 10 (18%) outcomes. When using standard survival analysis methods, patients were censored at the end of the follow-up (e.g., 3 days), upon ICU discharge (for RCTs that did not assess delirium beyond discharge) or upon death. Death was considered a competing risk in the survival analysis for only 1 (10%) of the 10 outcomes [24].

The daily presence/absence of delirium during follow-up was compared across interventions in 4 RCTs (7%) via binomial regression (n=1) [25], longitudinal logistic regression models (n=2) [26, 27], or a joint model for recurrent days of delirium plus the terminating event of ICU discharge/death (n=1) [28, 29].

Only 4 (8%) of the 48 RCTs with a delirium incidence primary outcome reported conducting an analysis, primary or secondary, of delirium incidence that included adjustment for baseline variables [23, 27, 30, 31].

Delirium composite outcome

Delirium-free days (DFD) and delirium- and coma-free days (DCFD) are composite outcomes, similar to ventilator-free days very commonly used in RCTs of mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU [32]. This composite outcome is often defined as the number of days that a patient is alive and free of delirium (or delirium and coma) during a fixed follow-up duration (e.g., 14 days), with patients who die during the follow-up often being assigned a value of 0 for this composite outcome. In trials where delirium is not assessed after ICU discharge, often the days between ICU discharge and the end of follow-up are assumed to be free of delirium. Delirium composite outcomes were reported in 11 (17%) RCTs, with 6 (9%), 2 (3%), and 3 (5%) RCTs reporting a delirium composite as only a primary only, both a primary and secondary (evaluated at different time points) and secondary only, respectively. A majority of the delirium composite outcomes were defined in delirium RCTs conducted on critically ill patients (8 of 11, 73%) (Additional File Table 5).

Five unique statistical methods were applied to the 13 delirium composite outcomes (Additional File Table 5). The most common method, applied to 11 (85%) of the 13 outcomes, was a non-parametric test to compare the distribution of the composite outcome across the intervention groups. The two-sample t test was used to compare the means of 4 (31%) composite outcomes, and Poisson regression was used for 2 (15%) composite outcomes (from the same RCT defined at days 8 and 30) [33]. The joint model, described above, was applied as a secondary analysis of the composite outcome in 1 (8%) RCT [34]. A single RCT was adjusted for baseline variables in the analysis of the delirium composite primary outcome [35].

Delirium duration outcome

Delirium duration was a primary or secondary outcome for 6 (9%) and 18 (28%) of 65 RCTs, respectively (Additional File Table 3). The majority (14 of 18, 78%) of RCTs reporting delirium duration as a secondary outcome were prevention trials. Delirium duration was defined up to a fixed number of days (13, 54%), until ICU discharge (6, 25%), or until hospital discharge (4, 17%).

The 24 delirium duration outcomes were analyzed using 5 unique statistical methods (Additional File Table 6): a non-parametric test (12, 50%), two-sample test for means (9, 38%), survival analysis (3, 13%), Poisson regression (2, 8%) [36, 37], and two-sample test for proportions (1, 4%) [38]. The use of a non-parametric test or two-sample test for means occurred with similar frequency when comparing delirium RCTs conducted among surgery and critically ill patients (Additional File Table 6). A single RCT conducted an analysis of delirium duration that included adjustment for baseline variables [39].

Delirium severity outcome

Delirium severity was the primary outcome for 8 (12%) RCTs (Additional File Table 3), with 5 of 12 (42%) treatment trials having delirium severity as the primary outcome. In addition, 8 (12%) RCTs had delirium severity as a secondary outcome, all of which were RCTs conducted among surgery patients and 7 (88%) of which were prevention trials (Additional File Table 7).

Delirium severity was compared across intervention groups using 2 approaches applying 3 unique statistical methods (Additional File Table 7). The first approach computed the worst delirium severity score during follow-up for each patient and applied a non-parametric test (10 of 16 outcomes, 63%) or a two-sample test for means (3, 19%). Alternatively, a longitudinal regression model was applied to the daily delirium severity scores (5, 31%). No RCT adjusted for baseline variables in the analysis of delirium severity.

Mortality and ICU length of stay

Mortality and ICU length of stay (LOS) are common secondary outcomes, used in 20 (31%) and 31 (48%) of the 65 RCTs, respectively (Additional File Table 3). In addition, approximately 25% of delirium trials reported mortality and ICU LOS even when not named as primary or secondary outcomes. Compared to trials conducted among surgery patients, trials conducted among critically ill patients were more likely to include mortality (11 of 17, 65% vs. 8 of 41, 20%) and ICU LOS (11 of 17, 65% vs. 17 of 41, 41%) as secondary outcomes.

Discussion

This systematic review focused on the design and analysis of delirium outcomes. We identified 65 RCTs conducted among ICU patients with a delirium-related primary outcome, the majority of which were delirium prevention trials, with considerable heterogeneity in both the maximum duration of participant follow-up and whether delirium assessments occurred after ICU discharge. To detect differences in delirium incidence across intervention groups, the most common delirium outcome, 8 unique statistical methods were used. Heterogeneity in statistical methods also occurred with less commonly used delirium outcomes, i.e., delirium composite, delirium duration, and delirium severity, with 5, 5, and 3 unique statistical methods reported, respectively. Heterogeneity in statistical methods was similar across the two main populations of patients enrolled in delirium RCTs; surgery and critically ill patients.

Heterogeneity across delirium RCTs is expected. Features of the target patient population and understanding of the proposed treatment mechanisms should drive choices for the design and selection of delirium outcome(s). Further, multiple statistical methods are often appropriate for analyzing the same delirium outcome and the choice of method(s) may depend on the accessibility of relevant statistical tools for both sample size estimation and data analysis. Given this issue and the goal of advancing methodologic recommendations, our findings support several key considerations for the design and analysis of delirium RCTs, as well as, highlight areas for future research including the need for developing statistical methods specific to the clinical features of delirium and obtaining consensus on the use of these methods among delirium clinical researchers (Table 4).

First, it is important to explicitly define delirium outcomes. Key features of a reported definition should include the maximum duration of follow-up, the frequency of delirium assessments, whether delirium is assessed after ICU discharge, and how patient mortality is incorporated, or accounted for, in the outcome. For example, a delirium RCT conducted among ARF patients may define delirium incidence as whether a patient screens positive for delirium at least once during any twice-daily assessment while alive in the ICU within 14 days of randomization. The definition of delirium composite outcomes should include how mortality is incorporated and how delirium and coma status is defined after ICU discharge, if delirium assessments are terminated at ICU discharge. Further, the consensus from key stakeholders (patients, families, and clinicians) on primary and secondary delirium outcome definitions is warranted and would improve the ability to harmonize results across delirium trials.

Second, statistical analysis methods for delirium outcomes should consider censoring due to ICU discharge and the competing risk of death. The occurrence of discharge creates a statistical and inferential issue known as informative censoring, as discharge can be correlated with delirium incidence, duration, and severity [40,41,42,43] and death precludes the occurrence of or resolution of delirium. The most frequently utilized two-sample test comparing the proportion of patients ever screened positive for delirium during follow-up (delirium incidence) or the mean duration of delirium may be sufficient to detect differences across intervention groups if delirium assessments occur after ICU discharge (or delirium is not expected after ICU discharge) and mortality rates are low, as expected in delirium RCTs conducted among surgery patients. However, when delirium assessments are terminated at ICU discharge with risk for post-discharge delirium or mortality rates are high, as expected in delirium RCTs conducted among critically ill ICU patients, comparisons of proportions or means may be misleading. For example, if patterns of mortality differ across intervention groups, a difference in the proportions may be detected even if the intervention had no impact on the incidence of delirium [12, 43]. Comparing the proportion of ever delirium patients defines the total effect, which includes the direct effect of the intervention on the incidence of delirium plus the effect mediated through death [41, 43, 44]. Comparisons of patterns of censoring or death across the interventions should be provided [45] and alternative survival analysis methods should be considered, but have yet to be fully evaluated for delirium RCTs [43]. Further, in delirium prevention trials conducted among critically ill patients, evaluating only the first occurrence of delirium ignores information from potentially recurring delirium episodes [28]. For this reason, the use of recurrent event survival methods offers an appealing alternative approach and is currently being extended to include the ability to account separately for ICU discharge and death as censoring events [16, 29, 46]. One additional type of censoring that should be considered in delirium RCTs conducted among critically ill patients is coma or deep sedation. Patients may be considered not at risk for delirium, with no delirium assessment conducted, during periods of coma or deep sedation [28], or coma or deep sedation may be considered part of the continuum of the delirium experience and included in the delirium outcome definition [47]. To our knowledge, the impact of treating coma or deep sedation as a censoring event has not been evaluated.

Third, delirium composite outcomes (e.g., days free of delirium and coma to 28 days) are common outcomes in RCTs targeting both prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill patients. In such RCTs, mortality may be ranked as the worst state and assigned a value of zero. In such cases, the average delirium composite outcome is not directly interpretable, requiring additional reporting of the components of the composite outcome (e.g., as secondary outcomes) [48]. Moreover, comparisons across intervention groups should be made using non-parametric tests that focus on the ranking of the numerical values of the composite outcome measure [48]. Further evaluation of composite outcomes is warranted in delirium RCTs that terminate assessments at ICU discharge to understand the behavior of these outcomes (i.e., type I error rate), when interventions may impact both onset and duration of delirium, as well as the length of ICU stay and mortality.

Lastly, baseline variables, which are prognostic for delirium incidence (e.g., age, APACHE II severity of illness score, receiving a sedative drug [49]), are often collected in delirium RCTs. However, only 6 (9%) of the 65 RCTs conducted an analysis, primary or secondary, of the primary delirium outcome that adjusted for baseline variables. Adjusting for baseline variables may improve the precision of statistical comparisons of delirium outcomes across intervention groups (i.e., increase statistical power) [50]. Robust statistical methods for baseline variable adjustment have been developed for a wide range of outcome types (e.g., binary, time to event, and rank-based composites) [51,52,53,54,55]. Exploring the utility of baseline variable adjustment in delirium RCTs is warranted.

Our systematic review has potential limitations. First, there may be errors or uncertainty (due to ambiguity in reporting) in the data abstraction. We sought to minimize by duplicate and independent data abstraction and carefully resolving any discrepancies, as well as utilizing data extractors with training in epidemiology and biostatistics. Second, it is possible that our systematic search or screening process inadvertently omitted some eligible RCTs. However, such omissions are unlikely to have been systematic, and given the size of our review and recurrent observations, is not expected to meaningfully alter our conclusions. Third, we chose to exclude trial registries from the systematic review. We did this so we could capture the primary and secondary analyses actually conducted (rather than those planned/proposed) for each delirium outcome since there are known instances of deviations (sometimes not reported clearly) of actual report vs. trial registry. However, we did review any Appendices/Supplementary Material (including study protocol) when included with the published trial when data elements of interest were not presented in the main manuscript. Fourth, our data collection for statistical methods did not include screening for adherence to CONSORT recommendations on reporting within RCTs [56]. For instance, analyses for binary outcomes should provide both a treatment effect and associated confidence interval with CONSORT recommending reporting both absolute risk difference and relative risk estimates. Our categories of statistical methods for two-sample tests for proportions include approaches, e.g., Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test, that do not necessarily adhere to these recommendations. Lastly, no formal consensus process or methodology was used to create our list of considerations with targets for future work since the focus of the paper is reporting the findings of the systematic review.

Conclusions

Specification of delirium outcome definitions and statistical analysis methods to compare intervention groups require careful consideration of the duration of follow-up, ability to assess delirium after ICU discharge, and expectation of patient mortality. Creating uniform standards for statistical analyses and reporting in delirium RCTs will improve the quality of individual trials and the ability to harmonize results across trials. Further evaluation and development of statistical methods are warranted to promote the selection of appropriate statistical analysis methods.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- NIDUS:

-

Network for Investigation of Delirium: Unifying Scientists

- MV:

-

Mechanically ventilated

- ARF:

-

Acute respiratory failure

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- DFD:

-

Delirium-free days

- DCFD:

-

Delirium- and coma-free days

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, Rockett C, Inouye SK, Sellke FW, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119:229–36.

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–10.

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–62.

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi JL, Thompson BT, Pun NE, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–16.

Mitchell ML, Shum DHK, Mihala G, Murfield JE, Aitken LM. Long-term cognitive impairment and delirium in intensive care: a prospective cohort study. Aust Crit Care. 2018;31(4):204–11.

Trzepacz PT, Bourne R, Zhang S. Designing clinical trials for the treatment of delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):299–307.

Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, Balas MC, Boustani MA, La Calle GH, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(9):1329–39.

Rose L, Agar M, Burry LD, Campbell N, Clarke M, Lee J, et al. Development of core outcome sets for effectiveness trials of interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium (Del-COrS): study protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016371.

Rose L, Agar M, Burry L, Campbell N, Clarke M, Lee J, et al. Reporting of outcomes and outcome measures in studies of interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium in the critically Ill: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(4):e316–24.

Contentin L, Ehrmann S, Giraudeau B. Heterogeneity in the definition of mechanical ventilation duration and ventilator-free days. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(8):998–1002.

Harhay MO, Ratcliffe SJ, Small DS, Suttner LH, Crowther MJ, Halpern SD. Measuring and analyzing length of stay in critical care trials. Med Care. 2019;57(9):e53–9.

Brock GN, Barnes C, Ramirez JA, Myers J. How to handle mortality when investigating length of hospital stay and time to clinical stability. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:144.

Wang C, Scharfstein DO, Colantuoni E, Girard TD, Yan Y. Inference in randomized trials with death and missingness. Biometrics. 2017;73(2):431–40.

Colantuoni E, Scharfstein DO, Wang C, Hashem MD, Leroux A, Needham DM, et al. Statistical methods to compare functional outcomes in RCTs with high mortality. BMJ. 2018;360:j5748.

Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Ely EW, Hopkins RO, Needham DM. Statistical approaches for evaluating interventions to reduce delirium in the ICU. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(7):534–6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Network for Investigation of Delirium: Unifying Scientists (NIDUS). Delirium measurement info cards. 2018. https://deliriumnetwork.org/measurement/delirium-info-cards/.

Burry L, Hutton B, Williamson DR, Mehta S, Adhikari NK, Cheng W, et al. Pharmacological interventions for the treatment of delirium in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9(9):CD011749.

Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM. Antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):2171-2173]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4):705–14.

Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, Wilson LM, Zhang A, Robinson KA, et al. Antipsychotics for treating delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(7):485–95.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2011. Available at: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/table_8_5_a_the_cochrane_collaborations_tool_for_assessing.htm.

Sauër AM, Slooter AJ, Veldhuijzen DS, van Eijk MM, Devlin JW, van Dijk D. Intraoperative dexamethasone and delirium after cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(5):1046–52.

Hakim SM, Othman AI, Naoum DO. Early treatment with risperidone for subsyndromal delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery in the elderly: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(5):987–97.

Al-Qadheeb NS, Skrobik Y, Schumaker G, Pacheco MN, Roberts RJ, Ruthazer RR, et al. Preventing ICU subsyndromal delirium conversion to delirium with low-dose IV haloperidol: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(3):583–91.

Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, Schmidt GA, Wright PE, Canonico AE, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):428–37.

Potharajaroen S, Tangwongchai S, Tayjasanant T, Thawitsri T, Anderson G, Maes M. Bright light and oxygen therapies decrease delirium risk in critically ill surgical patients by targeting sleep and acid-base disturbances. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:21–7.

Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Hough CL, Wozniak AW, Jackson JC, et al. Rosuvastatin for delirium and cognitive impairment in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: an ancillary study to a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(3):203–12.

Rondeau V, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Brouste V, Soubeyran P. Joint frailty models for recurring events and death using maximum penalized likelihood estimation: application on cancer events. Biostatistics. 2007;8(4):708–21.

Abbasi S, Farsaei S, Ghasemi D, Mansourian M. Potential role of exogenous melatonin supplement in delirium prevention in critically ill patients: a double-blind randomized pilot study. Iran J Pharm Res. 2018;17(4):1571–80.

Avidan MS, Maybrier HR, Abdallah AB, Jacobsohn E, Vlisides PE, Pryor KO, et al. Intraoperative ketamine for prevention of postoperative delirium or pain after major surgery in older adults: an international, multicentre, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):267–75.

Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1772–7.

Campbell NL, Perkins AJ, Khan BA, Gao S, Farber MO, Khan S, et al. Deprescribing in the pharmacologic management of delirium: a randomized trial in the intensive care unit. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):695–702.

Page VJ, Casarin A, Ely EW, Zhao XB, McDowell C, Murphy L, et al. Evaluation of early administration of simvastatin in the prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation (MoDUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):727–37 Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(4):e15.

Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, Hough CL, Rock P, Gong MN, et al. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506–16.

Álvarez EA, Garrido MA, Tobar EA, Prieto SA, Vergara SO, Briceño CD, et al. Occupational therapy for delirium management in elderly patients without mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Crit Care. 2017;37:85–90.

Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Campbell NL, Gao S, Khan SH, Wang S, et al. Preventing postoperative delirium after major noncardiac thoracic surgery-a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(12):2289–97.

Bakri MH, Ismail EA, Ibrahim A. Comparison of dexmedetomidine or ondansetron with haloperidol for treatment of postoperative delirium in trauma patients admitted to intensive care unit: randomized controlled trial. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2015;19:118–23.

van Eijk MM, Roes KC, Honing ML, Kuiper MA, Karakus A, van der Jagt M, et al. Effect of rivastigmine as an adjunct to usual care with haloperidol on duration of delirium and mortality in critically ill patients: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1829–37.

Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–9.

Geskus RB. Data analysis with competing risks and intermediate states. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2016.

Wolkewitz M, Cooper BS, Bonten MJ, Barnett AG, Schumacher M. Interpreting and comparing risks in the presence of competing events. BMJ. 2014;349:g5060.

Young JG, Stensrud MJ, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Hernan MA. A causal framework for classical statistical estimands in failure-time settings with competing events. Stat Med. 2020;39(8):1199–236.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509.

Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopind M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(6):648–53.

Cook R, Lawless J. The statistical analysis of recurrent events. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007.

van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Brüggemann RJM, Schoonhoven L, Beishuizen A, Vermeijden JW, et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(7):680–90.

Novack V, Beitler JR, Yitshak-Sade M, Thompson BT, Schoenfeld DA, Rubenfeld G, et al. Alive and ventilator free: a hierarchical, composite outcome for clinical trials in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(2):158–66.

van den Boogaard M, Schoonhoven L, Maseda E, Plowright C, Jones C, Luetz A, et al. Recalibration of the delirium prediction model for ICU patients (PRE-DELIRIC): a multinational observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(3):361–9.

Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med. 2002;21(19):2917–30.

Jiang F, Tian L, Fu H, Hasegawa T, Wei LJ. Robust alternatives to ancova for estimating the treatment effect via a randomized comparative study. J Am Stat Assoc. 2019;114(528):1854–64.

Colantuoni E, Rosenblum M. Leveraging prognostic baseline variables to gain precision in randomized trials. Stat Med. 2015;34(18):2602–17.

Díaz I, Colantuoni E, Hanley DF, Rosenblum M. Improved precision in the analysis of randomized trials with survival outcomes, without assuming proportional hazards. Lifetime Data Anal. 2019;25(3):439–68.

Moore KL, van der Laan MJJ. Increasing power in randomized trials with right censored outcomes through covariate adjustment. Biopharm Stat. 2009;19(6):1099–131.

Benkeser D, Carone M, Gilbert PB. Improved estimation of the cumulative incidence of rare outcomes. Stat Med. 2018;37(2):280–93.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–32.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Carrie Price MLS, Welch Medical Library, Johns Hopkins University, for developing the systematic review search strategy and citation extraction, as well as, Blair Anton MLS, MS, AHIP, Welch Medical Library, Johns Hopkins University, for peer review of the search strategy. The authors would like to thank the following collaborators from the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine or the Outcomes After Critical Illness and Surgery (OACIS) Group, Johns Hopkins University, who conducted hand searches, extracted study characteristics, and recorded study results: Albahi M Malik MBBS, David P Blackwood MD Msc, Sriharsha Singu MBBS, Darin Roberts MD, Elise Caraker BS, Sai Phani Sree Cherukuri MBBS, Pooja Kota MBBS, Rohit Aloor MD, Naga Preethi Kadiri MBBS, Nitin Soni MBBS, Gowthami Sai Kogilathota Jagirdhar MBBS, and Roshan Dinparatisaleh MD.

Funding

MOH was supported by R0HL141678 from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). XL, MK, VDD, DMN, KJN, and EC were supported by R01AG061384 from NIH. DMN was supported by R24HL111895 and R24AG054259 from the NIH. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC, KJN, VDD, and MOH contributed to the design of the systematic review. All authors except KJN contributed to the generation of data collection forms and data collection. EC, XL, MK, NA, and VDD contributed to the data analysis. EC, KJN, MOH, and DMN contributed to the data interpretation. The authors contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

KN reports grants from Hitachi, personal fees from Merck & Co, outside the submitted work; and DMN reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Haisco USA, outside the submitted work; the remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Section 1.

PRISMA checklist. Section 2. Search strategy. Section 3. Inclusion criteria. Section 4. Delirium outcome categories. Section 5. Statistical methods categories. Table 1. Individual study characteristics of the 65 delirium trials. Table 2. Individual study risk of bias assessments. Table 3. Frequency of primary and secondary delirium outcomes, mortality and ICU length of stay in the 65 delirium trials. Table 4. Statistical methods applied to delirium incidence, separately for delirium RCTs conducted among critically ill and surgery patients. Table 5. Statistical methods applied to the delirium composite, for all trials with a delirium composite outcome and separately for trials conducted among critically ill and surgery patients. Table 6. Statistical methods applied to delirium duration, for all trials with a delirium duration outcome and separately for trials conducted among critically ill and surgery patients. Table 7. Statistical methods applied to delirium severity, for all trials with a delirium severity outcome and separately for trials conducted among critically ill and surgery patients. Figure 1. Risk of bias analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Colantuoni, E., Koneru, M., Akhlaghi, N. et al. Heterogeneity in design and analysis of ICU delirium randomized trials: a systematic review. Trials 22, 354 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05299-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05299-1