Abstract

Background

Prescribing, monitoring and administration of medicines in care homes could be improved. A cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) is ongoing to evaluate the effectiveness of an independent prescribing pharmacist assuming responsibility for medicines management in care homes compared to usual care.

Aims and Objectives

To conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation of the RCT, in line with Medical Research Council (MRC) process evaluation guidance, to inform interpretation of main trial findings and if the service is found to be effective and efficient, to inform subsequent implementation.

Objectives

-

1.

To describe the intervention as delivered in terms of quality, quantity, adaptations and variations across triads and time.

-

2.

To explore the effects of individual intervention components on the primary outcomes.

-

3.

To investigate the mechanisms of impact.

-

4.

To describe the perceived effectiveness of relevant intervention components [including pharmacist independent prescriber (PIP) training and care home staff training] from participant [general practitioner (GP), care home, PIP and resident/relative] perspectives.

-

5.

To describe the characteristics of GP, care home, PIP and resident participants to assess reach.

-

6.

To estimate the extent to which intervention delivery is normalised among the intervention healthcare professionals and related practice staff.

Methods

A mix of quantitative (surveys, record reviews) and qualitative (interviews) approaches will be used to collect data on the extent of the delivery of detailed tasks required to implement the new service, to collect data to confirm the mechanism of impact as hypothesised in the logic model, to collect explanatory process and final outcome data, and data on contextual factors which could have facilitated or hindered effective and efficient delivery of the service.

Discussion

Recruitment is ongoing and the trial should complete in early 2020. The systematic and comprehensive approach that is being adopted will ensure data is captured on all aspects of the study, and allow a full understanding of the implementation of the service and the RCT findings. With so many interrelated factors involved it is important that a process evaluation is undertaken to enable us to identify which elements of the service were deemed to be effective, explain any differences seen, and identify enablers, barriers and future adaptions.

Trial registration

Date registered: 15 December 2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medication management in care homes is suboptimal [1]. Despite various policy recommendations [2,3,4,5,6,7], the majority of care home residents continue to receive inappropriate medication, and a significant number of administration errors occur [8]. Many residents are on multiple medications, and there is overuse of psychotropic medicines, as well as more general concern such as lack of biochemical monitoring of high-risk drugs including methotrexate, azathioprine, amiodarone, warfarin etc. and lack of regular medication review [9]. Further, there is often poor communication between general practitioner (GPs), care home staff, community pharmacists, residents and their relatives, and a need for training of care home staff, many of whom may not have a theoretical understanding of the requirements for supply, storage, recording and administration of medicines. High staff turnover and the frailty of the resident population are further factors. It has been suggested that errors would be reduced if a single person took on overall responsibility for the medicines management in care homes. Our team proposed this should be a pharmacist independent prescriber (PIP) linked to the care home, and are undertaking a programme of work which has identified logistical and professional barriers to a PIP care home service, and devised solutions to address them [10], devised a training programme for the PIPs to ensure they have the requisite competencies to deliver the service, and identified provisional measures of outcome [11] in preparation for a definitive cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) to compare the outcomes from the PIP service with usual care. A mixed-methods non-randomised feasibility study [12] confirmed the acceptability and feasibility of the processes for participant identification, recruitment and informed consent. The PIP service was found to be acceptable to all stakeholders and benefits were reported by GPs and care home staff. Appropriate outcome measures and tools were confirmed and minor refinements were made to the service specification and RCT protocol. The definitive cluster RCT is ongoing and will complete in May 2020. An internal pilot within the definitive trial has confirmed: (i) the feasibility of recruiting and randomising sufficient GP practices, PIPs, care homes and residents; (ii) the availability of data for primary outcome at 3 months; (iii) confirmation that there are no intervention-related safety concerns and (iv) researcher blinding and unblinding [12].

The definitive RCT was approved by ethics committees in England and Scotland, and registered with the ISRCTN registry (registration number ISRCTN 17847169). A protocol paper (protocol version 5 1.7.18) for the main trial, following SPIRIT guidance, has been submitted to BMC Trials [13]. This current article describes the protocol for the Process Evaluation Protocol that accompanies the definitive RCT; it follows the 2014 guidance on process evaluations [14, 15] and details are in Process Evaluation Protocol version 4 11.12.18 available from the authors on request.

Causal assumptions

The definitive RCT is evaluating the efficacy and efficiency of implementing and delivering a PIP service and comparing outcomes for care home residents who receive the PIP service with outcomes for residents who continue to receive usual care [13]. In total 44 GP/PIP/care home groups (subsequently referred to as triads) and 880 patients will be included in four geographical areas of East Anglia, Leeds, North East Scotland and Northern Ireland. As noted above, the problem is that medicines management in care homes is suboptimal and complex, because the frailty and comorbidities of residents means many are on multiple medications. A logic model was developed (Additional file 1: Appendix 1) to demonstrate how the proposed PIP service could address the various issues. The PIP intervention is described below.

The intervention

At intervention care home(s), PIPs working in collaboration with the relevant GP(s), will assume responsibility for the medicines management of a mean of 20 care home residents living in one or more care homes associated with the GP practice. To ensure competency in professional role and study procedures, the recruited PIPs are qualified independent prescribers, and have attended a 2-day face-to-face training programme, which included an overview of the trial design, project delivery, and preparation for the role; the service specification and completion of the Pharmaceutical Care Plans (PCPs). This was followed by time to develop relationships with medical practices (for those unfamiliar with the practice), care homes and community pharmacists, including performing medication reviews with GPs and observing medication administration by care staff, before final sign-off by clinically qualified professionals independent of the research team.

A service specification for the PIPs has been developed iteratively in the earlier stages of the project, and is attached (Additional file 1: Appendix 2). In summary, it includes:

reviewing a participating resident’s medication and developing and implementing a PCP

assuming prescribing responsibilities

supporting systematic ordering, prescribing and administration processes within each care home, GP practice and supplying pharmacy where needed

providing training to staff in care home and GP practice

communicating with GP practice, care home, supplying community pharmacy and study team

The control arm

At each control care home, medicine management is according to usual practice, in which the GP(s) has responsibility for the medicines management of care home residents living in one or more care homes associated with the GP practice. Pharmacy provision is also according to usual practice in that area.

The CHIPPS RCT process evaluation

The aims of the process evaluation, described in this article are informed by the logic model and the stages of the Medical Research Council (MRC) process evaluation framework [14, 15]. These are listed below.

- 1.

To describe the intervention as delivered in terms of quality, quantity, adaptations and variations across triads and time (Table 1).

- 2.

To explore the effects of individual intervention components on the primary outcomes (Tables 2 and 3).

- 3.

To investigate the mechanisms of impact (Table 2).

- 4.

To describe the perceived effectiveness of relevant intervention components (including PIP training and care home staff training) from participant (GP, care home, PIP and resident/relative) perspectives (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

- 5.

To describe the characteristics of GP, care home, PIP and resident participants to assess reach (Table 4).

- 6.

To estimate the extent to which intervention delivery is normalised among the intervention healthcare professionals and related practice staff (Table 4).

- 7.

If the service is found to be effective and efficient, to inform subsequent implementation.

Methods

Design

In line with the MRC guidance on process evaluation [14, 15] this mixed-methods process evaluation using qualitative and quantitative approaches will collect data on implementation of the intervention, mechanisms of impact, outcomes and contextual factors. The tasks, aims, data and data source for each of these are summarised in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4. All data is collected, from intervention arm participants only, after the 6-month study period is completed for an individual participant.

Implementation

Data will be collected on the effectiveness of the training, and the services delivered by the PIPs (see Table 1 below) to provide an understanding of whether the PIPS were adequately prepared for the role and the fidelity with which it was delivered.

Mechanism of impact

Data will be collected to confirm the mechanism of impact of the intervention in achieving the desired aim of improved patient quality of care (Table 2). This section draws particularly on the logic model and hypotheses for addressing the highlighted issues. Data will only be collected from the intervention group to see if any observed differences in outcomes between the groups can be explained by different components of the PIP service. None of these happen in the control (usual care) group.

Outcomes

The outcomes that are collected and which will be used in the process evaluation are described in Table 3. The selected outcomes are those where there is a clear link to the intervention proposed and where they inform the process.

Contextual factors

Any contextual factors identified which might have affected the delivery and impact of the intervention are described in Table 4. This information may include factors related to individual personnel and organisations as well as macro-level issues such as Care Quality Commission requirements or head office requirements.

Data collection methods

The following text refers to the data sources identified in Tables 1–4 .

Quantitative

Data sources related to training and pharmacist competency

Training feedback: At each PIP training event, PIPs are asked to complete a feedback form at the end of the 2-day face-to-face session

Pre-intervention competency: Following the training, PIPs submit their competency framework to one of the study competency assessors who discuss these with the PIP and signs them off as ‘fit to practise’ as a CHIPPS PIP, prescribes further training or that they are not competent to deliver the study

Review of PCPs: Following an agreed process (Additional file 1: Appendices 3 and 4) a random 20% of PCPs are reviewed for appropriateness by study team members who are specialists in care of the elderly. Whilst this process is primarily about safety, the assessment templates also capture data on missed opportunities.

Data sources related to activity

PIP activity log: Intervention PIPs are asked to keep an activity log of their daily activity detailing the time spent on tasks as listed in the service specification (Additional file 1: Appendix 2)

PIP survey: Following each phase, intervention PIPs will be asked to complete a short questionnaire asking about their experiences and the extent to which they delivered aspects of the intervention focusing especially on non-medication review aspects of the service specification (the NoMAD survey [16]).

Data sources related to prescribing

Most of the prescribing-associated data is collected as part of the main trial processes to assess effectiveness and efficiency of the intervention (GP records, healthcare utilisation, falls records, hospitalisations and deaths) and processes are detailed in the main trial protocol (version 5 1.7.18). The following lists additional data collected as part of the process evaluation

Adverse events: Adverse events which are not deemed serious are reported using a standard template emailed to the Clinical Trials Unit. All study participants with a professional role (PIP GP, GP staff and care home staff) are made aware of this template and are asked to use this facility if they suspect any adverse event, whether or not there is a perceived causal relationship with the intervention

PCPs: these are completed by the PIP as a clinical record of their actions including the rationale for these. Data extraction from these will inform the details of medication changes that underpin the global measures such as total number of medicines, British National Formulary categories most involved in changes, and overall Drug Burden Index (DBI). They will also include information on homely remedies and medications available from pharmacies (P medicines) and other retail outlets (general sale list medicines) which could result in therapeutic duplication

Data sources related to variability

Variability may be due to inherent non-modifiable differences across participating organisations, sites and individuals, or to the way the CHIPPS service has been delivered or normalised. The former will be explored using subgroup analyses and the latter by general estimating equations (GEEs) and applying normalisation process theory (NPT) via a NoMAD [16] survey to all participating GPs, PIPS and care home staff at the end of each phase. These are described below.

Subgroup analyses: The following subgroup analyses will be conducted.

- i.

Comparison of intervention effect by care home types, i.e. nursing versus residential.

- ii.

Comparison of intervention effect by the employment status of the PIPs, i.e. those PIPs who were previously employed, and therefore had an established working relationship, with the study GP practice, and those who were not).

For both of the above an interaction term (between treatment and subgrouping factor) will be added to the primary model and formally tested for a non-zero value.

- i.

GEEs: Any effect of the PIP intervention is likely to be mediated through a decrease in the DBI. This will be tested using a GEE, adjusting for group membership (this is in order to remove any effect of the PIP intervention on falls mediated via a different causal route).

NoMAD survey [16]: The NoMAD survey is an implementation measure based on the Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) [17, 18]. The survey form includes preliminary demography and general questions about experiences and satisfaction followed by four sections each relating to one of the NPT domains of coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring.

Qualitative

Feedback from all stakeholders on their experiences and views of the intervention is a core part of this process evaluation. This will help contextualise the intervention and increase understanding of the process of implementation and any variation between sites and stakeholders.

Interviews

At the end of each phase of the intervention a purposive sample of up to three of each of GPs, care home managers, staff, residents and relatives (if available) in each of the four geographical areas will be invited to take part in a semi-structured interview. Sampling will be based on a maximum variation sample to reflect differences in site and PIP characteristics, e.g. PIP employment status, previous PIP experience, demographic profile of care home residents, rural or urban location. All PIPS will be invited to take part in an interview.

Interviews will be guided by a topic guide (Additional file 1: Appendix 5), developed from the qualitative outputs from the earlier non-randomised feasibility study [12]. Topics will include participants’ views of the PIP service implementation and delivery, communication between staff, perceived effectiveness of the intervention and the identification of any unintentional consequences. All aspects of the service will be probed and there will be specific probes for unforeseen effects to understand whether anything else about the service impacted positively or negatively on patient care or cost-effectiveness. In addition to the above topics, the PIP interview will explore their perception of the training programme and its utility.

Conduct and analysis

All participants invited to interview will be given an information sheet and consent form prior to participation. Ideally, interviews will be held face to face at a location of the interviewee’s choice, but virtual modes will be considered for logistical reasons. All proceedings will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis will draw on the NPT framework, but an inductive approach will enable recognition of unexpected emergent themes. Data will be managed in NVIVO.

Documentary evidence

Minutes of meetings will provide researcher-reported information on barriers, facilitators and other confounding factors that may have affected delivery of the trial, e.g. (recruitment challenges, reach).

Data integration/synthesis

Once all process and main trial outcomes are reported, all the data sets (qualitative and quantitative) will be integrated [19] using a triangulation approach to consider agreement, partial agreement, silence and dissonance across the findings. This will identify relevant actions, and clarify and relate causal pathways to experiences, providing an enriched means to explain unexpected outcomes, and identify optimal intervention contexts. Should the main RCT findings suggest the CHIPPS service is effective and efficient, the process evaluation will inform recommendations for implementation into routine services. The process evaluation will also be interrogated to understand reasons why the intervention has not been successful, including variable success rates in different sites.

Discussion

This detailed mixed-method process evaluation will provide an in-depth understanding of the interactions, barriers and facilitators which underpin the main study quantitative findings. For example, it will provide evidence of the effectiveness of the training in preparing the PIPs to deliver their role, show to what extent the mechanism of impact – improved medication management – has been implemented and the barriers and facilitators that have been encountered. Learning from these will enable decisions to be made about future roll-out of the PIP service. Further, if the main trial does not demonstrate that there has been an improvement in patient outcomes, it will allow an informed judgement to be made as to whether the service is wrong in principle or whether its implementation has been suboptimal. Our findings will be especially pertinent and timely as PIPs are already being introduced into care homes for roles such as we are evaluating. The systematic and comprehensive approach that is being adopted is in line with the MRC guidance on process evaluations [14, 15]. It will ensure data is captured on all aspects of the study, and allow an understanding of the implementation of the service, confirm its mechanism of impact, explore secondary, possibly explanatory, outcomes and any contextual factors. In summary, with so many interrelated factors involved it is important that a process evaluation is undertaken to enable identifyimg which elements of the service were deemed to be effective and explain any differences seen whilst also identifying adaptions, enablers and barriers.

Trial status

Resident recruitment for the RCT began in February 2018 and will continue until October 2019. Recruitment for the process evaluation started spring 2019 and will continue until June 2020.

Availability of data and materials

Requests for access to the data will be considered, and approved in writing where appropriate, after formal application to the Trial Management Committee/Programme Steering Committee [13]. Considerations for approving access are documented in the Project Management Group/Programme Steering Committee Terms of Reference [13].

References

Alldred D, Raynor D, Hughes C, Barber N, Chen T, Spoor P. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD009095.

Department of Health: Implementation resurce for the use of medicines in care homes for older people. DH Alert [online] 2010.

NHS England. Clinical pharmacists. https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/gpfv/workforce/building-the-general-practice-workforce/cp-gp/. Accessed 10 July 2019.

Scottish Government. Primary Care Services – pharmacists. https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/Health/NHS-Workforce/Pharmacists/Pharmacy. Accessed 10 July 2019.

NHS Wales. Clinical pharmacists in GP practices. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/news/40188. Accessed 10 July 2019.

Health and Social Care Board. Practice based pharmacists. http://www.hscboard.hscni.net/our-work/integrated-care/gps/investment-in-gp-practices/. Accessed 10 July 2019.

Wickware C. Government announces extra role for pharmacists in care homes as part of £3.5bn funding package. Pharm J. 2018;301:7920. https://doi.org/10.1211/PJ.2018.20205790.

Fadya Al-Hamadani. Medicines management in care homes. PhD thesis Cardiff University. http://orca.cf.ac.uk/123409/1/2019fadyaphd.pdf.

Barber N, Alldred D, Raynor D, et al. The care homes use of medicines study: prevalence, causes and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:341–6.

Bond CM, Lane K, Poland F, et al. Care homes independent pharmacist prescribing study (CHIPPS): GP views on the potential role for pharmacist independent prescribers within care homes. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(s2):6.

Millar A, Daffu-O’Reilly A, Hughes CM, et al. Development of a core outcome set for effectiveness trials aimed at optimising prescribing in older adults in care homes. Trials. 2017;18(1):175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1915-6.

Inch J, Notman F, Bond C, et al. A non-randomised feasibility study of independent pharmacist prescribing in care homes. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0465-y#citeas Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

Bond C, Holland R, Alldred D, et al. Protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of independent pharmacist prescribing in care home: the CHIPPS study. Trials. 2020;21:103.

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. London: MRC Population Health Science Research Network; 2014.

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258.

NoMaD survey. http://www.normalizationprocess.org/npt-toolkit/. 2020. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

May C, Finch T, Mair F, et al. Understanding the implementation of complex interventions in health care: the normalization process model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:148.

May C, Mair FS, Finch T, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4:29.

A O’C, E M, J N. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4587.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the research team who have or are contributing daily to deliver the process evaluation (University of East Anglia: Laura Watts, Joanna Williams, Bronwen Harry, Jeanette Blacklock, Caroline Hill, Frances Johnston; University of Aberdeen: Jacqueline Inch, Frances Notman, Lindsay Dalgarno; University of Leeds: Amrit Daffu-O'Reilly; Queen's University Belfast: Mairead McGrattan); PPIRes (Public and Patient Involvement in Research) for being formal collaborators on the grant and for advice on ongoing conduct of the study as represented by Kate Massey (sadly deceased) and Christine Handford. We thank Ian Small lead primary care medicines management pharmacist in Norwich (now retired) and a co-applicant on the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) programme grant. On behalf of the CHIPPS Team, we would also like to acknowledge NHS South Norfolk Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) as the study sponsor and host of PPIRes, and especially Clare Symms, Norfolk & Suffolk Primary and Community Care Research Office for her contribution towards management of the study budget.

Dissemination policy

Trial results will be communicated to participants, other healthcare professionals, the public, and other relevant groups via local dissemination events, briefing papers, publications in academic and professional journals, conference presentations and other invited speaker events. These results will include the relevant findings from the process evaluation. The PPI representatives will be especially involved in advising on dissemination to the residents, relatives and care home stakeholders, and the wider public. The main trial results will be reported on the study website (https://www.uea.ac.uk/chipps) and via social media, e.g. the study Twitter account (@CHIPPS_Study), but these may not include all the process evaluation unless directly relevant.

Funding

This study is funded by the NIHR [Programme Grants for Applied Research (grant reference number RP-PG-0613-20007)]. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Other than receiving routine monitoring reports, the funders have had no further involvement in the design and conduct of the trial or any input to this manuscript. A copy of the manuscript has been sent to them for information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

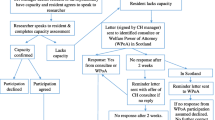

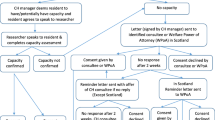

The study has been approved by both the East of England Research Ethics Committee (REC) and the Scottish REC. Approval in both countries was required because of differences in national laws for involving subjects lacking capacity to consent. Research and development approvals have also been secured as necessary for all NHS organisational units involved. All subsequent amendments are submitted as necessary to the relevant committee and not enacted until approval awarded. All participants were formally invited and consented in line with the processes described previosuly.

Consent for publication

No individual person’s data in any form is included in this manuscript. In the reporting of the findings from the process evaluation anonymised quotes may be used. Consent for this has been confirmed.

Competing interests

None of the investigators, grant holders or any of the research team members has any financial or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Appendix 1. CHIPPS Logic Model v8, 31/10/2018 CHIPPS Logic Model v8, 31/10/2018. Appendix 2. Care Homes Independent Pharmacist Prescribing Study (CHIPPS) Service Specification. Appendix 3. Review of Pharmaceutical Care Plans. Appendix 4. CHIPPS PCP reviews – reporting template. Appendix 5. Topic guides for interviews and focus groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bond, C.M., Holland, R., Alldred, D.P. et al. Protocol for the process evaluation of a cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of independent pharmacist prescribing in care home: the CHIPPS study. Trials 21, 439 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04264-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04264-8