Abstract

Background

Cognitive problems in people with schizophrenia predict poor functional recovery even with the best possible rehabilitation opportunities and optimal medication. A psychological treatment known as cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) aims to improve cognition in neuropsychiatric disorders, with the ultimate goal of improving functional recovery. Studies suggest that intervening early in the course of the disorder will have the most benefit, so this study will be based in early intervention services, which treat individuals in the first few years following the onset of the disorder. The overall aim is to investigate different methods of CRT.

Methods

This is a multicentre, randomised, single-blinded, controlled trial based in early intervention services in National Health Service Mental Health Trusts in six English research sites. Three different methods of providing CRT (intensive, group, and independent) will be compared with treatment as usual. We will recruit 720 service users aged between 16 and 45 over 3 years who have a research diagnosis of non-affective psychosis and will be at least 3 months from the onset of the first episode of psychosis. The primary outcome measure will be the degree to which participants have achieved their stated goals using the Goal Attainment Scale. Secondary outcome measures will include improvements in cognitive function, social function, self-esteem, and clinical symptoms.

Discussion

It has already been established that cognitive remediation improves cognitive function in people with schizophrenia. Successful implementation in mental health services has the potential to change the recovery trajectory of individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. However, the best mode of implementation, in terms of efficacy, service user and team preference, and cost-effectiveness is still unclear. The CIRCuiTS trial will provide guidance for a large-scale roll-out of CRT to mental health services where cognitive difficulties impact recovery and resilience.

Trial registration

ISRCTN, ISRCTN14678860, Registered on 6 June 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schizophrenia is a relatively common disorder with a lifetime risk of around 1% [1]. It typically has an onset in late adolescence or early adulthood, so can derail the academic, interpersonal and employment achievements that prepare a person for adult roles and responsibilities [1]. It is also associated with an average loss of life-span of up to 20 years [2], poor employment prospects and difficulty in achieving satisfying social relationships. Poor prognosis is established soon after illness onset, with estimates of sustained social and occupational recovery being only 17–25% in the first 5 years [3]. Although positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) are a hallmark of a diagnosis of schizophrenia, cognitive dysfunction is apparent prior to the onset of psychosis and remains unchanged despite symptom remission [4, 5]. Poor cognition in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia is a key predictor of poor functional outcome [6, 7] and impairments are noticeable in about 96% of all outpatients [8]. It is cognitive function at psychosis onset, and not symptom profile or response to treatment, that most strongly predicts social and occupational functioning 4 years later [9]. Cognitive difficulties also limit the rate of improvement using evidence-based rehabilitation, so that those who have the most difficulty will gain least [6]. Interventions that can boost cognition or maintain cognitive reserve would be beneficial, as these improvements are likely to have wide-ranging effects on service outcomes.

Owing to the potential for chronicity and morbidity, the economic burden of schizophrenia is immense. In the UK, it was estimated as £19b in 2012, and for each patient each year as £60k in societal costs and £36k in public sector costs (Schizophrenia Commission 2012 [10]) with similar figures found in the USA [11]. Much of the social burden is due to lost employment, housing and benefits [12]. New UK mental health policies, such as ‘No health without mental health’ [13], stress the need for early intervention to make long-lasting differences in people’s lives. With such a poor prognosis and high costs as well as personal burden, it is vital to explore whether new therapies can improve the recovery trajectory and thus decrease costs. Embedding cognitive treatments early, as in early intervention services (designed for clients who undergo intensive case management over the first 3 years of illness), may confer potentially long-lasting benefits.

Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) was developed to address cognitive problems in people with schizophrenia. The Cognitive Remediation Experts Workshop in 2012 [14] defined it as ‘an intervention targeting cognitive deficit using scientific principles of learning with the ultimate goal of improving functional outcomes’ (p. 1). The largest meta-analysis (> 2000 participants in 40 studies) demonstrated that CRTs provide durable benefits in global cognition (effect size, 0.45) and functioning (Cohen’s d effect size, 0.42) [15] against any control group. New evidence and systematic reviews were taken into consideration by the Scottish Guideline Network for Healthcare Improvement Scotland [16] (extending the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines of 2014 [17]) and CRT is now recommended in Scotland. Because of this wealth of evidence, other countries, such as Australia, Italy and Japan, and the New York State mental health services now include it in their guidance.

Cognitive remediation experts [14] recommend that ‘the effect on functioning is enhanced when provided in a context (formal or informal) that provides support and opportunity for extending everyday functioning’ p. 1. This is based on evidence that CRT boosted outcomes in other evidence-based therapies [18, 19]. One study, based in an early invention for psychosis services, also demonstrated that CRT can halve the number of cognitive behaviour therapy sessions needed for the same symptom reduction, reducing costs [19]. Early intervention services provide multimodal therapies, as well as contact with social and employment services. They therefore offer formal and informal opportunities for the translation of gains, as well as the potential to boost CRT outcome and improve the potential for changing recovery trajectories and sustaining benefits.

Cognitive remediation studies in younger people demonstrate acceptability and benefit in the short and longer term for cognitive and functional domains [20,21,22]; secondary analyses show greater gains for younger participants [23, 24]. There is ample evidence of biological and cognitive effects in schizophrenia, in which loss of brain grey matter [25, 26] and network disconnectivity occurs early in the disorder, but also evidence that CRT offers neuroprotective effects against grey matter loss [27] and improves brain activation [28]. As CRT has been shown to be effective for younger people and has the potential to improve functioning, it may be most beneficial if interventions are delivered at the earliest opportunity. There was optimism that early intervention services would have longer-term benefits but, despite quick access to multimodal treatments, it has been difficult to demonstrate that short-term improved outcomes were durable [29,30,31], although individual studies show better results [32]. On the whole, the results are like those of Bertelsen and colleagues [33] that, irrespective of receiving early intervention services, 60% of service users were neither working nor studying 5 years after psychosis onset. Clearly the current ingredients of recovery-focused treatments are not achieving their full potential for later function. This trial has also taken a recovery-focused approach and highlights those outcomes of relevance to an individual. Our primary outcome measure is, therefore, the important functional goal as chosen by the participant.

Cognitive remediation therapy is an evidence-based intervention but what is not obvious is the mode of implementation necessary and who would benefit most from different therapeutic modalities. Cognitive remediation therapies have been provided with high therapist involvement or very little, and at different intensity levels. We therefore developed the arms of the trial to represent the most frequently used implementation methods. The first is an intensive therapy that has previously been used by our team [34], which depends on continuous therapist support. The second arm is one adopted in many studies, where treatment is provided in a group with therapeutic support [35]. We have shown that our current therapy is suitable for such a group-intervention [36] approach. The final arm is one that depends on more independent access to therapy and has been used in several trials with differing effects [37, 38]. The main differences between these implementation methods is the level of therapist support and therefore the costs of implementation, with the most independent being the cheapest. Although the presence or absence of therapist support did not affect cognitive outcomes [14], therapist support has been shown to have tangible effects [39] and service users have positive views about therapists being present during therapy [40, 41]. Balancing the cost of the service, service user preferences and outcomes has not been tested as there have been no direct comparisons using the same cognitive remediation programme with differing levels of therapist support. The question of what is the best implementation method therefore has clinical equipoise. Cognitive remediation therapies have also generally been tested in single-centre studies so the effect of differing background services on outcomes has also not been tested. Therefore, this large, multicentre trial was developed, with the main aim of determining the best way of introducing CRT for psychosis into UK National Health Service (NHS) early intervention services in order to optimise individual functional outcomes and costs.

We consulted people with experience of using mental health services at every stage of trial development as well as clinicians and carers, mindful of the finding of Ennis and Wykes [42] that patient involvement is associated with study success. For example, clinicians do not routinely introduce the idea of cognitive difficulties at psychosis onset to service users. To address this sensitive issue, we consulted service users, carers and mental health clinicians through focus groups and developed three study leaflets, which were approved by an ethics committee, to accompany the participant information sheet. We also consulted the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre Young Person’s Mental Health Research Advisory group about the design, wording of the protocol, participant information sheet, consent form and other promotional material for the trial.

Trial aims and objectives

The aim is to determine the best method of introducing CRT for psychosis in UK NHS early intervention services to optimise individual functional outcomes and costs. The objectives are to compare three methods of CRT delivery on: (a) the degree to which participants have achieved their stated goals using the Goal Attainment Scale as the primary outcome measure; (b) improvement in cognition, social function, self-esteem and symptoms (the secondary outcome measures); (c) cost-effectiveness; )d) satisfaction of the service users and staff involved in the implementation.

Methods

Trial design

This is a multicentre, blinded, randomised, controlled trial conducted in the early intervention services of UK NHS Mental Health Trusts. Three different methods of providing CRT (intensive, group or independent) and treatment as usual within each of six research sites will be compared on their ability to improve real-world outcomes. In addition, implementation methods will be compared on their acceptability to service users, and the cognitive, clinical and real-world outcomes and cost-effectiveness, using a net-benefit approach. The site is designed to compare different services; catchment areas of the participating trusts range from high-density inner city to suburban and so cover diverse populations and different service backgrounds. Outcomes are measured at 0 (baseline), 15 (post-treatment) and 39 (follow-up) weeks after randomisation (see Additional file 1).

Trial governance

The oversight of the trial is undertaken by a steering committee which, in addition to statistical and trial advisors, includes a service user and carer. In addition, an ECLIPSE service user advisory group meets three times a year to advise on any problems and to provide feedback on trial progress. The trial was registered at ISRCTN (ref.: 14678860), a primary clinical trial registry recognised by the World Health Organization and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. The trial was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the National Research Ethics Service NHS Committee (Camden and King’s Cross Research Ethical Committee, ref. 15/LO/1960).

Participants

Participants will be recruited from NHS early intervention services across six research sites in England (Birmingham, Coventry and Warwickshire, East Anglia, North London, South London, and Sussex).

Inclusion criteria

-

(a)

Attending an early intervention service and at least 3 months from the onset of the first episode of psychosis; clinical stability, as judged by the clinical team

-

(b)

Aged between 16 and 45

-

(c)

Research diagnosis of non-affective psychosis, i.e. schizophrenia, schizo-affective or schizophreniform disorder following assessment

-

(d)

Ability to give informed consent

These entry criteria were developed following discussion with staff, service users and carers to ensure a pragmatic approach. For example, the requirement for clinical stability will exclude a proportion of service users but this will be the approach used in reality to ensure that individuals can cope with the demands of the therapy, including regular attendance. It is also an entry criterion that both staff and service users recommended for the trial. The age criterion is the one adopted in early intervention services. The decision to consider individuals as potential participants after 3 months is based on the establishment of individuals into treatment in early intervention services following initial stabilisation after the acute episode.

Exclusion criteria

-

(a)

Not able to communicate in English sufficiently to participate in cognitive testing

-

(b)

Suffering from an underlying organic or neurological condition affecting cognition, e.g. traumatic brain injury or seizure disorder

-

(c)

Have a comorbid diagnosis of intellectual disability

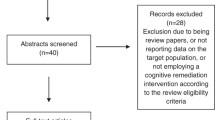

At each site, the early intervention services clinicians will be asked to identify service users with a non-affective psychosis. Early intervention services clinicians will approach patients individually to ascertain permission for the research team to approach. Written consent will be obtained by trained research workers. After a consent form is signed, the researchers confirm the diagnosis by completing the relevant sections of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (sections A ‘Major depressive episode’, D ‘Manic or hypomanic episode’ and L ‘Psychotic disorders’) [43]. Trial withdrawal will be recommended by the early intervention services clinician who provides treatment as usual. Figure 1 provides the participant flow chart; the enrolment schedule is provided in Fig. 2.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments. CANTAB, Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery; CRT, cognitive remediation therapy; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQOL five dimensions questionnaire; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; TAU, treatment as usual; WASI II, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence – Second Edition; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Task; WTAR, Wechsler Test of Adult Reading

Allocation and blinding

Therapists use secure email to send a list of (11–15) consenting and assessed participants to the King’s Clinical Trials Unit, which allocates each participant using pre-generated randomisation lists. The randomised allocations are sent back to the therapist by secure email. The pre-generated randomisation lists are stored by the King’s Clinical Trials Unit in an access-restricted electronic folder that is not accessible to any members of the study team. The therapist informs each of the participants of their allocated trial arm.

Randomisation is stratified by research site in the proportion 4:4:3:4 (Group CRT, independent CRT, intensive CRT, treatment as usual) to make efficient use of therapist resources. Alternative randomisation allocations will be used if 15 participants cannot be recruited within the stipulated 12-week recruitment period, with a minimum block of 11 participants (reducing the proportions in the independent CRT and treatment-as-usual arms only so as not to break the group design constraint or reduce the number of participants in the intensive CRT arm). This flexibility allows more efficient use of therapist time and resources as the therapist time is limited and the intensive therapy absorbs a lot of this resource.

The whole team, apart from the therapists and the randomisation statistician, are blind to participant group allocation. Breaches will be recorded; if a breach is to a research assessor, another research worker will complete the assessment. An audit of the quality of the blinding will be conducted at the end of the study.

Participant data are entered online into a secure electronic data capture system hosted by the King’s Clinical Trials Unit separately from treatment allocation data. Data quality and audit are regularly tested prior to and after data entry. Analysis scripts are agreed and finalised by the senior statistician prior to unblinding.

Interventions

The CRT interventions (intensive, group, independent) will be carried-out using the CIRCuiTS computerised cognitive remediation programme; CIRCuiTS is based on a successful paper-and-pencil therapy and was developed with service users and therapists to increase engagement with younger clients who value computerised therapy [44, 45]. The three CRT delivery modes will differ in the associated hours of therapist contact but all participants will be offered 42 treatment hours. A treatment-as-usual arm will be evaluated, as CRT is not yet recommended in England by NICE; this will allow us to assess cost-effectiveness. All trial participants will continue to receive standard care throughout the trial.

Therapy will be delivered at each site by an experienced assistant psychologist trained in CRT at the trial centre and supervised centrally on a weekly basis. Each therapist will provide all three types of CRT over the therapy period.

-

(a)

Intensive CRT. Participants will receive 10.5 weeks of twice weekly therapy, up to 42 h in total, with sessions lasting between 60 and 180 min, split into three parts: (1) 20–60 min of CRT with a therapist; (2) 20–60 min of in-vivo transfer work (i.e. putting CRT strategies into real life) with a therapist; (3) 20–60 min of independent CRT, set up by the therapist on-site, or off-site in the service user’s own time.

-

(b)

Group CRT. Participants randomised in this arm will be offered 14 weeks of thrice weekly group therapy (up to 42 h of CRT). Group sessions will last up to 90 min, with attendance for at least 20 min considered as a completed session. Groups have closed membership, with four participants per group and one therapist. The sessions will begin and end with group activities, relating to goal setting and metacognition. During the rest of the session, service users will work independently on CIRCuiTS tasks, with the therapist offering help and support on an as-needed basis.

-

(c)

Independent CRT. Participants will receive one individual session with the therapist for orientation followed by up to 41 sessions when they will work independently (up to 42 h of CRT in total). To support the independent sessions, the therapist will offer telephone contact or attendance at drop-in sessions on an as-needed basis to address any questions or problems (but not exceeding 1 h contact time per fortnight). A session will be considered ‘valid’ if it lasts a minimum of 20 min.

-

(d)

Treatment as usual. This will be the standard input offered by the treating team without restrictions. Standard care involves clinical contact with the team on a daily, weekly or monthly basis depending on recovery. It also involves opportunities to be involved in educational or employment programmes, other psychological therapies, e.g. cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis and medical treatments, including drug therapies. Participants randomised to the treatment-as-usual group will not receive CRT therapy.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure of the trial is the degree to which participants achieve their personal goals, as measured by the Goal Attainment Scale [46, 47] 15 and 39 weeks after randomisation. The Goal Attainment Scale is a method of scoring the extent to which participant’s individual goals (set at baseline) are achieved during the intervention. In effect, participants each have their own outcome measure but this is scored in a standardised way to allow statistical analysis. The goals are individually identified to suit the participant, and the levels are individually set around their current and expected levels of performance. The Goal Attainment Scale has been adopted in several studies of psychosocial interventions in mental health [48, 49]. It has been shown to be a reliable method of rating behaviours by self-report, which is comparable, but not identical, to informant and researcher reports, and has wide use in studies of cognitive rehabilitation and in clinical practice [50,51,52].

The secondary outcome measures, some of which are used in the cost-effectiveness analysis, are: (a) social and occupational functioning, as measured by the Time Use Survey [53] and the EuroQOL five dimensions questionnaire [54]; (b) use of services, as measured by the Client Service Receipt Inventory [55]; (c) self-esteem, as measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [56]; and (d) cognition, as measured by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (which includes the following tests: Reaction Time, One-Touch Stockings of Cambridge, Paired-Associates Learning, Attention Switching Task, Rapid Visual Information Processing, Spatial Working Memory and Emotion Recognition Task) and supplemented by the Computerized Wisconsin Card Sorting Task [57], Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [58], Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure [59] and Digit Span forwards and back test [60]. We also collect some background data to investigate treatment mechanisms, including the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence [61] and metacognition measures. A description of these outcomes is presented in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Data are collected by trained research assistants, whose reliability is assessed regularly. Consistency between sites is achieved by regular review by members of the management and research teams as well as data quality checks at the site and by audit through the trial statistician.

Measurement

Power

We have the capacity to recruit 900 patients (from 1500 patients attending 10 services for 3 years) and have allowed for a 20% drop-out pre-randomisation. Using a design with parallel arms of equal size, with 180 patients per arm, provides approximately 80% power for a simple group effect size difference of 0.3. This increases to 91% for outcomes that correlate 0.5 with baseline (both calculated using sampsi in Stata).

Freidlin et al. [62] suggest no great advantage in accounting for multiple testing in a multi-arm trial, and also that the advantages of a larger treatment-as-usual arm are more slight than commonly assumed. Interaction among patients in group delivery is very slight so no allowance for clustering was thought necessary.

The power calculation is based on arms of equal size; the difference in power as a result of the unequal allocation is likely to be small as the use of modestly unequal randomisation ratios only very slightly reduces the power of a study [63].

Analysis

The primary outcome measure will be group differences in Goal Attainment Scale T-score [47] at 15 weeks post-randomisation, tested using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model co-varying for Goal Attainment Scale T-score at baseline and adjusting for site as a fixed effect. Pairwise comparisons will be conducted between each of the CRT arms and treatment as usual, with significance and confidence intervals calculated using nominal values of p. Data will be analysed under intention-to-treat assumptions. Treatment effects for secondary outcomes will be analysed in a similar way. For the primary outcome, given the probable differences in treatment uptake (adherence), local average or complier average treatment effects compared with treatment as usual will also be estimated. Using assigned arm as an instrumental variable, all arms will be examined together to estimate the effect of hours of active CRT. On an assumption of a common per-hour effect across arms, some residual information will be available to estimate residual direct effects of treatment mode.

The cost-effectiveness analysis will be conducted from the perspectives of health and social care and society (including informal care, lost employment). Service use, collected using the Client Service Receipt Inventory, will be combined with appropriate unit cost information [64] and added to the intervention costs. Costs will be compared between groups using bootstrapped regression models to address the probable skewed distribution. Cost-effectiveness will be assessed by combining costs and outcome measures (primary outcome measure and quality-adjusted life years) in the form of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

If one arm has lower costs and better outcomes than another, it will be ‘dominant’. However, there will be uncertainty around the estimates of incremental costs and outcomes; this will be explored using cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. The cost-effectiveness planes will be produced by generating and plotting (via bootstrapped regression models) 1000 incremental cost–outcome pairs. This will allow us to determine the probability that each arm has better outcomes and higher costs, better outcomes and lower costs, worse outcomes and lower costs, or worse outcomes and higher costs than the comparator. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves will be generated using the net-benefit approach, whereby the incremental gain in quality-adjusted life years is multiplied by a range of threshold values for a quality-adjusted life year (including those used by NICE) and subtracting the incremental cost. This will be performed on 1000 bootstrapped incremental cost–outcome pairs and the proportion that are above zero will indicate that that one arm is more cost-effective than another. Sensitivity analyses will be conducted by varying key cost parameters. In particular, we will increase or decrease the intervention cost by 10%, 25% and 50% and use alternative methods for valuing informal care (e.g. minimum wage, unit cost of a homecare worker).

Interim analysis

Given that CRT is known to be effective, we want to ensure that we do not adopt all four trial arms if one treatment arm provides little benefit compared with the remainder, so we will carry out an interim intention-to-treat analysis. This will be undertaken by the health economist, using data from the first 195 patients (using the post-therapy data at 15 weeks post-randomisation). This analysis may result in one of the trial arms being closed, with an immediate impact on the randomisation of the next patients.

The decision to drop an arm will be taken by an independent data monitoring committee and will depend on the resultant cost of therapy and other services and goal attainment. The costs will include direct therapy inputs and other services derived from the Client Service Receipt Inventory.

The direct therapy costs will be calculated from data on the number and length of sessions, number of attendees (for group therapy) and unit costs, based on staff grade and overheads. Cost-effectiveness planes will be generated by plotting the 1000 incremental cost–outcome combinations for each pair of comparators. This will tell us the probability that one therapy has (i) lower costs and better outcomes, (ii) lower costs and worse outcomes, (iii) higher costs and better outcomes, or (iv) higher costs and better outcomes than a comparator.

Governance and monitoring

The trial is sponsored by King’s College London, overseen by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) appointed ECLIPSE program steering committee, to which the trial’s independent data monitoring committee report. All members of the data monitoring committee are independent of the trial (are not involved with the trial in any other way and do not have competing interests that could impact the trial). The membership of all the committees can be found in Additional file 2: Table S2. The data monitoring committee is the only body involved in the trial that has access to the unblinded comparative data. It will receive and review the progress and accruing data of the trial and provide advice on the conduct of the trial to the trial steering committee. The role of its members is to monitor these data and make recommendations to the program steering committee on whether there are any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. Further details can be found in the data monitoring committee charter, which is based on DAMOCLES study group guidance [65]. Adverse events are reviewed by local principle investigators and stored locally. Serious adverse events are reported (emailed) within one working day to the local principle investigator and trial co-ordinator using password-protected forms. All serious adverse events are reviewed by a chief investigator to make a decision on whether or not they are definitely, possibly, or not related to the study intervention and whether they are expected or unexpected. All serious adverse events are anonymised and sent to a designated member of the data monitoring committee for their decision on whether they must be reported to the research ethical committee.

Discussion

Service user involvement

Service user involvement is an integral part of this study. Service users not only contributed to the study design but have also helped us develop the information sheets and consent forms and the publicity for the study, as well as advising us on how to approach potential participants. A service user and carer are also part of our steering committee. However, we have also chosen to meet our service user advisory group separately so that we can explain in more detail the issues we face and what our potential solutions might be. They can then provide advice that is not under time pressure or in the context of a large body of academics who may speak in jargon. This method of involvement has been suggested as important to ensure that service users feel they can provide worthwhile feedback [66]. Regular meetings are held to describe the recruitment, challenges and successes and the group is asked to advise on specific issues. The decisions of the user advisory group are then implemented and the minutes are available at meetings of the steering committee. Following advice on the effectiveness of user involvement [67, 68], we will ensure that our user advisory group provides value to our whole research programme by interviewing a sample of investigators each year to uncover and resolve any problems between the user group and the team. We will also ask the service user advisors to provide anonymous feedback on whether they think there are issues that have not been resolved satisfactorily or advice they feel that we ignored.

Main challenges

The challenges fall into three areas: a changing context in the NHS; the availability of resources within teams; and block randomisation. Early intervention services have changed since the study was designed, as they now have specified waiting times and follow new NICE guidance on therapy packages. Both changes have affected how referrals are managed within teams. To overcome the new pressures, we will work closely with the clinical teams, team managers and care coordinators to ensure that the trial is not adding to these pressures. First, a full-time cognitive remediation therapist will be included in the early intervention team to provide early intervention staff an opportunity to refer their clients to CRT who might be on a waiting list for other therapy. Second, researchers will assist early intervention staff with risk-assessment reports (e.g. symptom assessments) and share a brief report on participant cognitive measures with the clinical teams, which will help them in their care programme approach for each individual, irrespective of whether they are involved in active therapy. Detailed cognitive assessments are usually not available in early intervention services, so this will be a benefit of choosing to take part in the trial.

Resources are always a difficulty, e.g. there may be a lack of suitable therapy rooms for CRT in some services, and we aim to help teams locate finance to re-use some unfurnished rooms. As CRT is not in NICE guidance, there is also a lack of experienced senior therapists who can provide specific supervision to more junior staff within a trust. We have responded by employing a senior clinical psychologist to offer this additional support across the sites and ensure continuity over the trial.

We developed our original block randomisation so that we could use the therapy resources as efficiently as possible and so blocks were defined as 15 participants. However, we potentially waste therapy resources with slow participant acquisition. Hence, we changed the blocks so that in some circumstances we can reduce the number of individuals who can be randomised. As with all trials there is a need to ensure blind assessment so we have also trained additional staff from each of the sites to provide extra support with some research procedures that might break the blind, e.g. inspecting clinical notes, and we will provide alternative raters in the case of any unblinding.

Participant engagement and dissemination

Relevant research information will be available on the website, which is currently being developed (especially designed with participants in mind), as well as other social media (i.e. Twitter). This website will host presentations and peer-reviewed journal articles as they are produced to ensure accessibility. We will share our findings with our participants and participating teams through this method and also by sending newsletters at regular intervals to update them on the progress of the projects. Following advice from our user advisory group, participants will receive Christmas cards along with other promotional materials.

Providing advice to the NHS

We are mindful that advice on implementation needs to come from different perspectives. Our three implementation models vary by therapist input and we will therefore have some detail on the effects on our key outcome variable, which is defined from the participants’ perspective – their goals as measured by the Goal Attainment Scale. But this is not all we will be measuring. We have the perspective of the service user participants on satisfaction with therapy and the method of provision, including therapy drop-out and the number of sessions received. We are collecting staff views so that we know what they consider appropriate levels of commitment and resource, as well as the organisational facilitators and barriers. We will include a provider perspective through the costs and cost-effectiveness of the different methods of providing therapy. All these perspectives will allow us to provide a balanced view of the different intervention methods so as to optimise their effects.

As well as a comprehensive overall plan for the best implementation method, our data will also allow us to discover whether therapy might need to be tailored to different individuals to provide the best effect. We will therefore investigate whether individual characteristics can predict larger or smaller benefits and, importantly, whether therapy might have a negative effect in some people. We will also investigate whether organisational factors, such as staff resources and background treatments, might affect successful CRT implementation.

All this information will allow: (i) policy makers to plan for this treatment; (ii) individual teams to understand what is required before and during implementation; and (iii) service users to receive the best individualised care to improve their recovery potential. Another of our work packages involves producing and evaluating an online training resource for this form of cognitive remediation. Together with the information on tailoring, this trial will allow smooth roll-out of the therapy into NHS services. Finally, the ECLIPSE programme will provide an implementation guide using the best available data.

Trial status

Research protocol, version 1.3, 1 March 2017.

Recruitment start date, 1 June 2017; predicted recruitment end date, 1 January 2020.

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- CIRCuiTS:

-

Computerised Interactive Remediation of Cognition – Training for Schizophrenia

- CRT:

-

Cognitive remediation therapy

- ECLIPSE:

-

Building Resilience and Recovery through Enhancing Cognition and Quality of Life in the Early Psychoses

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health Research

References

Jaaskelainen E, Haapea M, Rautio N, Juola P, Penttila M, Nordstrom T, Rissanen I, Husa A, Keskinen E, Marttila R, et al. Twenty years of schizophrenia research in the Northern Finland birth cohort 1966: a systematic review. Schizophr Res Treat. 2015;2015:524875.

Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, Broadbent MTM, Fernandes AC, Lee WE, Hotopf M, Stewart R. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19590.

Wunderink L, Sytema S, Nienhuis FJ, Wiersma D. Clinical recovery in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:362–9.

Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Poulton R, Harrington H, Murray RM. Childhood developmental risk factors for schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders in the Dunedin birth cohort. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:26–7.

Leeson VC, Sharma P, Harrison M, Ron MA, Barnes TRE, Joyce EM. IQ trajectory, cognitive reserve, and clinical outcome following a first episode of psychosis: a 3-year longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:768–77.

Wykes T. Predicting symptomatic and behavioral outcomes of community care. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:486–92.

Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK. Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:41–51.

Morice R, Delahunty A. Frontal executive impairments in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:125–37.

Leeson VC, Harrison I, Ron MA, Barnes TRE, Joyce EM. The effect of cannabis use and cognitive reserve on age at onset and psychosis outcomes in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:873–80.

Schizophrenia Commission. The abandoned illness. Rethink. 2012. https://www.rethink.org/media/514093/TSC_main_report_14_nov.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

Insel TR. Assessing the economic costs of serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatr. 2008;165:663–5.

Mangalore R. Cost of schizophrenia in England. London: Personal Social Services Research Unit; 2006.

Her Majesty's Government. No health without mental health: a cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. Crown. 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213761/dh_124058.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

Cognitive Remediation Experts Workshop. Cognitive Remediation Experts Workshop Meeting. Florence: Schizophrenia International Research Society; 2012.

Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatr. 2011;168:472–85.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of schizophrenia: a national clinical guideline. 2013. http://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-131-management-of-schizophrenia.html. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

NICE. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. National Institute for Care and Excellence. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG178. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, Wolfe R, Pascaris A. Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatr. 2007;164:437–41.

Drake R, Day CR, Picucci R, Warburton J, Larkin W, Husain M, Reeder C, Wykes T, Marshall M. Combing cognitive remediation and cognitive-behavioral therapy after first episode schizophrenia: a naturalistic, randomised, controlled trial. Florence: Schizophrenia International Research Society; 2012.

Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Cooley SJ, DiBarry AL, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS. Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia: effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1468–76.

Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. One-year durability of the effects of cognitive enhancement therapy on functional outcome in early schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:210–6.

Wykes T, Newton E, Landau S, Rice C, Thompson N, Frangou S. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007;94:221–30.

Corbera S, Wexler BE, Poltorak A, Thime WR, Kurtz MM. Cognitive remediation for adults with schizophrenia: does age matter? Psychiatry Res. 2017;247:21–7.

Wykes T, Reeder C, Landau S, Matthiasson P, Haworth E, Hutchinson C. Does age matter? Effects of cognitive rehabilitation across the age span. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:252–8.

Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, Gochman P, Blumenthal J, Nicolson R, Toga AW, Rapoport JL. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11650–5.

Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M. Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their relationship to clinical outcome – a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:585–94.

Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Cho RY, Prasad KMR, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. Neuroprotective effects of cognitive enhancement therapy against gray matter loss in early schizophrenia results from a 2-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:674–82.

Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, Bray P, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J. Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy – functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:144–52.

Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, Christensen TO, Krarup G, Jorgensen P, Nordentoft M. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:762–71.

Nordentoft M, Ohlenschlaeger J, Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Bertelsen M. Deinstitutionalization revisited: a 5-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of hospital-based rehabilitation versus specialized assertive intervention (OPUS) versus standard treatment for patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1619–26.

Gafoor R, Nitsch D, McCrone P, Craig TKJ, Garety PA, Power P, McGuire P. Effect of early intervention on 5-year outcome in non-affective psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:372–6.

Amminger GP, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, Harris MG, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Herrman H, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD. Outcome in early-onset schizophrenia revisited: findings from the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre long-term follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;131:112–9.

Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, Le Quach P, Christensen TO, Krarup G, Jorgensen P, Nordentoft M. Course of illness in a sample of 265 patients with first-episode psychosis – five-year follow-up of the Danish OPUS trial. Schizophr Res. 2009;107:173–8.

Reeder C, Huddy V, Cella M, Taylor R, Greenwood K, Landau S, Wykes T. A new generation computerised metacognitive cognitive remediation programme for schizophrenia (CIRCuiTS): a randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2720–30.

Twamley EW, Thomas KR, Burton CZ, Vella L, Jeste DV, Heaton RK, McGurk SR. Compensatory cognitive training for people with severe mental illnesses in supported employment: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.005.

Cella M, Reeder C, Wykes T. Group cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: exploring the role of therapist support and metacognition. Psychol Psychother. 2016;89:1–14.

Loewy R, Fisher M, Schlosser D, Carter C, Niendam T, Ragland JD, Biaganti B, Amirfathi F, Vinogradov S. Improved cognition and positive symptoms with targeted auditory processing training in recent-onset schizophrenia. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:114.

Donohoe G, Dillon R, Hargreaves A, Mothersill O, Castorina M, Furey E, Fagan AJ, Meaney JF, Fitzmaurice B, Hallahan B, et al. Effectiveness of a low support, remotely accessible, cognitive remediation training programme for chronic psychosis: cognitive, functional and cortical outcomes from a single blind randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001982.

Cella M, Wykes T. The nuts and bolts of cognitive remediation: exploring how different training components relate to cognitive and functional gains. Schizophr Res. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.09.012.

Rose D, Wykes T, Farrier D, Doran A-M, Sporle T, Bogner D. What do clients think of cognitive remediation therapy?: a consumer-led investigation of satisfaction and side effects. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2008;11:181–204.

Contreras NA, Lee S, Tan EJ, Castle DJ, Rossell SL. How is cognitive remediation training perceived by people with schizophrenia? A qualitative study examining personal experiences. J Ment Health. 2016;25:260–6.

Ennis L, Wykes T. Impact of patient involvement in mental health research: longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:381–6.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33.

Medalia A, Revheim N. Computer assisted learning in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatr Rehabil Skills. 1999;3:77–98.

Reeder C, Pile V, Crawford P, Cella M, Rose D, Wykes T, Watson A, Huddy V, Callard F. The feasibility and acceptability to service users of CIRCuiTS, a computerized cognitive remediation therapy programme for schizophrenia. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2016;44:288–305.

Kiresuk TJ, Smith A, Cardillo JE. Goal attainment scaling: applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale, Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994.

Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:362–70.

Battle CC, Imber SD, Hoehnsar R, Stone AR, Nash ER, Frank JD. Target complaints as criteria of improvement. Am J Psychother. 1966;20:184.

Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling – general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J. 1968;4:443–53.

Hurn J, Kneebone I, Cropley M. Goal setting as an outcome measure: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:756–72.

Williams RC, Stieg RL. Validity and therapeutic efficacy of individual patient goal attainment procedures in a chronic pain treatment center. Clin J Pain. 1986;2:219–28.

Rockwood K, Joyce B, Stolee P. Use of goal attainment scaling in measuring clinically important change in cognitive rehabilitation patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:581–8.

Lader D, Short S, Gershuny J. The time use survey 2005: how we spend our time. London: Office for National Statistics; 2005.

Beecham J, Knapp M. Costing psychiatric intervention. In: Thornicroft G, editor. Measuring mental health needs. London: Gaskell; 2001.

EuroQol Group. EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Revised edn with a new introduction. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press; 1989.

Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test manual: revised and expanded. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993.

Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Rey A, Osterrieth PA. Translations of excerpts from Andre Rey’s Psychological examination of traumatic encephalopathy and PA Osterrieth’s The complex figure copy test. Clin Neuropsychol. 1993;7(1):4–21.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – 4th Edition (WAIS-IV). San Antonio: NCS Pearson; 2008.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence – 2nd Edition (WAIS-II). San Antonio, TX: NCS Pearson; 2011.

Freidlin B, Korn EL, Gray R, Martin A. Multi-arm clinical trials of new agents: some design considerations. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4368–71.

Pocock SJ. Clinical trials: a practical approach. Chichester: Wiley; 2013.

Department of Health. NHS Reference costs. Crown. 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/nhs-reference-costs. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

Ellenberg SS, Fleming TR, DeMets DL. Data monitoring committees in clinical trials: a practical perspective. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2002.

Staley K. Exploring impact: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Eastleigh: NIHR; 2009.

Crepaz-Keay D. Effective mental health service user involvement: establishing a consensus on indicators of effective involvement in mental health services. DProf thesis, Middlesex University; 2014.

Robotham D, Wykes T, Rose D, Doughty L, Strange S, Neale J, Hotopf M. Service user and carer priorities in a biomedical research centre for mental health. J Ment Health. 2016;25:185–8.

Acknowledgements

TW and AP acknowledge the support of the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. TW also acknowledges her NIHR Senior Investigator Award. EJ acknowledges support of the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals. MB acknowledges part funding by the NIHR CLARHRC West Midlands.

Funding

The ECLIPSE programme grant is funded by the National Institute for Health Research in England (ref. RP-PG-0612-20002).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TW and EJ conceived the study, developed the original trial protocol and created the first draft of the paper. TV coordinated the programme and created the first draft of the paper. AW coordinates the programme and developed the design. AP contributed to the statistical analysis and original trial protocol and edited the draft paper. PM contributed to the design of the study and edited the draft paper. MB and SJ are investigators who contributed to the protocol and edited the draft paper. SS was an investigator who contributed to the original protocol. DS contributed to the design, provided the statistical analysis and edited the paper. DF is an investigator who contributed to the design. MT and KG are investigators. RU and JP are investigators who contributed to design and edited the draft paper. RT contributed to the treatment provision. MC contributed to the treatment design. CR contributed to the original protocol and the treatment design. GA and SD contributed organisational understanding for the design. DR provides service user expertise and also contributed to the development and the design of the study. All authors contributed to both the trial protocol and to this paper by critical review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The main trial (ECLIPSE Study 9: Implementation of Remediation into Early Intervention Services) has been reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the Camden and Kings Cross RES NHS Committee (ref. number 15/LO/1960). Additional file 2 contains the participant information and consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CR and TW created the cognitive remediation programme, CIRCuiTS, used in this trial but have no financial interests. No other authors have any competing financial or non-financial interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

SPIRIT 2013 checklist. (DOCX 41 kb)

Additional file 2:

Supplemental information. Table S1: Description of measures; Table S2: Membership of committees; Participant information sheet; Consent form. (DOCX 978 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wykes, T., Joyce, E., Velikonja, T. et al. The CIRCuiTS study (Implementation of cognitive remediation in early intervention services): protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 19, 183 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2553-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2553-3