Abstract

Background

Fast-track surgery (FTS), also known as enhanced recovery after surgery, is a multidisciplinary approach to accelerate recovery, reduce complications, minimise hospital stay without increasing readmission rates, and reduce health care costs, all without compromising patient safety. The advantages of FTS in abdominal surgery most likely extend to gynaecological surgery, but this is an assumption, as FTS in elective gynaecological surgery has not been well studied. No consensus guidelines have been developed for gynaecological oncological surgery although surgeons have attempted to introduce slightly modified FTS programmes for patients undergoing such surgery. To our knowledge, there are no published randomised controlled trials; however, some studies have shown that FTS in gynaecological oncological surgery leads to early hospital discharge with high levels of patient satisfaction. The aim of this study is whether FTS reduces the length of stay in hospital compared to traditional management. The secondary aim is whether FTS is associated with any increase in post-surgical complications compared to traditional management (for both open and laparoscopic surgery).

Methods/design

This trial will prospectively compare FTS and traditional management protocols. The primary endpoint is the length of post-operative hospitalisation (days, mean ± standard deviation), defined as the number of days between the date of discharge and the date of surgery. The secondary endpoints are complications in both groups (FTS versus traditional protocol) occurring during the first 3 months post-operatively including infection (wound infection, lung infection, intraperitoneal infection), post-operative nausea and vomiting, ileus, post-operative haemorrhage, post-operative thrombosis, and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Enquiry II score.

Discussion

The advantages of FTS most likely extend to gynaecology, although, to our knowledge, there are no randomised controlled trials. The aim of this study is to compare the post-operative length of hospitalisation after major gynaecological or gynaecological oncological surgery and to analyse patients’ post-operative complications. This trial may reveal whether FTS leads to early hospital discharge with few complications after gynaecological surgery.

Trial registration number

NCT02687412. Approval Number: SCCHEC20160001. Date of registration: registered on 23 February 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Fast-track surgery (FTS), also known as enhanced recovery after surgery, was initiated in 1995 by Bardram et al. [1]. FTS is a multidisciplinary approach to accelerate recovery, reduce complications, minimise hospital stay without increasing re-admission rates, and reduce healthcare costs, all without compromising patient safety [2]. FTS has been adopted by gynaecological, colorectal and upper GI specialities worldwide, and has been used successfully in non-malignant gynaecological surgery [3, 4], and is especially effective in elective colorectal surgery [5-7].

The speed of post-operative recovery is influenced by multiple factors including pain, post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), paralytic ileus, fatigue, and sleep disturbances. A multimodal approach to prevent and minimise these factors is considered essential to enhance recovery [2, 5, 6, 8]. Fast-track principles include providing the patient with thorough pre-operative information and education concerning pre-, intra- and post-operative care, the use of safe and short-acting anaesthetics, optimal dynamic pain relief with minimal use of opioids, management of PONV, enteral nutrition and early mobilisation, and the use of minimally invasive surgery [9].

The advantages of FTS documented in abdominal surgery most likely extend to gynaecological surgery; however, this is an assumption because FTS in elective gynaecological surgery has not been well studied. One study has shown that FTS in gynaecological oncology provides early hospital discharge and high levels of patient satisfaction [10]. However, no consensus guidelines have been developed for gynaecological oncological surgery although surgeons have attempted to introduce slightly modified FTS programmes for patients undergoing such surgery. To our knowledge, no randomised controlled trials have been published [3, 11, 12].

In traditional surgical care, patients are often admitted to hospital the day before the planned surgery, undergo pre-operative mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation, and receive ongoing intravenous fluids to maintain fluid balance prior to surgery or anaesthesia. Intra-operatively, patients are often volume-loaded to maintain filling pressures, receive pelvic drains to prevent fluid collection, then spend 2–3 days nil by mouth until bowel sounds return before beginning a graduated diet of clear liquids, free fluids, light diet, and finally a regular diet 5–7 days post-surgery. Patients are discharged an average of 5–7 days post-surgery [13]. FTS or enhanced surgical recovery programmes have been developed and refined in many specialities with documented improved patient outcomes, earlier discharge from hospital, and reduced post-operative length of stay (LOS) [2, 14, 15].

The aim of this study is to analyse the post-surgical complications in patients receiving FTS who are discharged earlier than anticipated after major gynaecological or gynaecological oncological surgery.

Methods/design

Objectives and hypothesis

This prospective study will compare FTS and traditional management protocols and test the following hypotheses:

H0: length of stay and post-operative complications are equal in both groups.

H1: length of stay is enhanced in the FTS group and post-operative complications differ between groups.

Study population and eligibility criteria

The trial is designed as a randomised, controlled, non-blinded, single-centre trial in the Department of Gynaecological Oncology of the Si Chuan Cancer Hospital Chengdu, Sichuan, China.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients scheduled for gynaecological oncology surgery (including radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy, hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy, and cytoreductive procedures for both open and laparoscopic surgery);

-

2.

Age: ≥ 18 years;

-

3.

Signed informed consent provided.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients with a documented infection at the time of surgery;

-

2.

Age ≥ 71 years;

-

3.

Patients with ileus at the time of surgery;

-

4.

Patients with hypocoagulability;

-

5.

Patients with psychological disorders, alcohol dependence, or drug abuse history;

-

6.

Patients with primary nephrotic or hepatic disease;

-

7.

Patients with severe hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg.

Criteria for discontinuing

-

1.

The trial appears to be causing unexpected harm or severe adverse events to participants, or evidence that the risks outweigh the benefits, with a discontinuance decision from the ethics committee.

-

2.

The enrollment indicates the trial cannot be completed in the 3-month period.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation is based on the LOS with a standard deviation in the traditional group of 1.5 based on previous studies [16, 17].

We estimate that in a superiority trial with an effect size of 90% and a margin of 10 (alpha 5%, power 90%) where μα = 1.96 and μβ = 1.28, using the equation n = [2(μα + μβ) σ /δ]2, a sample size of 47 patients per group is necessary to detect a difference between the groups. With an expected dropout rate of 20%, we plan to enrol 120 patients in the study.

Method of generating the allocation sequence

Computer-generated random numbers and list of any factors for stratification. To reduce predictability of a random sequence, details of any planned restriction (e.g. blocking) should be provided in a separate document that is unavailable to those who enrol participants or assign interventions.

Post-operative data collection

A daily assessment of the study patients will be made by clinical investigators or a delegated physician. Patients will be randomised when the surgery is booked. All protocol-required information collected during the trial will be entered into the patient’s record including: (1) patient characteristics, (2) hospitalisation information, (3) post-operative information, and (4) complications. Patient characteristics data will include: age, weight, height, body mass index, medical insurance status, blood pressure, glycaemia, lipidemia and performance status. Hospitalisation details will include LOS, the procedure performed, diagnosis, operating time, and intra-operative estimated blood loss. Post-operative details will include time to full tolerance of free fluids (days), time to full tolerance of solid food (days), and time to drain removal (days), admission to ICU, return to operating room, blood transfusion, venous thromboembolism (VTE), readmission to hospital, and malignancy status and hospitalisation expenses.

Complications (Table 1) details will include infection (wound infection, lung infection, intraperitoneal infection), PONV, ileus, post-operative haemorrhage, post-operative thrombosis, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Enquiry (APACHE) II score (Table 2).

Primary and secondary endpoints

Primary endpoints

LOS (days (d), mean ± standard deviation (SD)), which is defined as the number of days between the date of discharge and the date of surgery.

Secondary endpoints

Complications: complications in both groups are assessed during the first 21 days hospitalisation expenses post-operatively and include infection (wound infection, lung infection, intraperitoneal infection), PONV, ileus, post-operative haemorrhage, post-operative thrombosis, and APACHE II score (Table 2).

Ethics, study registration and consent

This trial was approved by an independent ethics committee at Sichuan Cancer Hospital and Research Institute.

Board Affiliation: Sichuan CHRI

Telephone: +86 02885420681; email: scchgcp@163.com

The study procedures, risks, benefits and data management will be discussed with patients before they are asked to provide informed consent to participate.

Study treatment

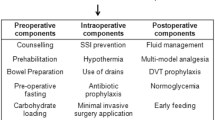

The surgical technique is standardised for the treatment team, and patients’ families are not blinded to the study. Data collectors are not involved in the clinical management of patients to ensure statistical validity and reliability. All surgeries are performed by the same team of surgeons, and patients are treated and nursed by the same treatment team during the pre-operative period. Post-operative complications are based on patient complaints and clinical symptoms. Given that there are no FTS guidelines for gynaecological oncological surgery, we refer to the guidelines for gastrectomy, colorectal surgery, and pancreaticoduodenectomy (Table 2 and Fig. 1) [18–20].

Safety

Gynaecological oncological surgery is highly technically demanding. To avoid bias based on the surgical learning curve, every surgical procedure will be performed or supervised by a senior surgeon. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants.

Methods for avoiding bias

Minimising systemic bias

Patients will be randomised to one of the two groups after admission. Randomisation will be accomplished using balanced permutation blocks by generating random numbers to obtain homogeneity between groups. Opaque, sealed envelopes will be labelled with the randomisation number and will contain a sheet stating the group allocation for the patient. Randomisation envelopes will be used in consecutive order. Basic patient characteristics and the day of randomisation will be documented on a data sheet so that compliance to the randomisation scheme can be checked retrospectively. If patients are excluded from the study after randomisation, their numbers will not be reused. Operating surgeons, attending physicians, nursing staff, and patients and families cannot be blinded in this study, as the procedures differ between groups; however, outcome assessors will not be blinded. The randomisation process will follow the CONSORT guidelines (Fig. 2) [21].

Minimising treatment bias

Gynaecological oncological surgery (including radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy, hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy, and cytoreductive procedures) are standardised in both groups, and all surgeons participating in the study are familiar with these procedures, which are commonly and routinely performed, thus eliminating a learning curve.

Minimising measurement bias

LOS and post-operative complications, which are the primary and secondary endpoints, will be based on data in the patient’s record. Blinding is not necessary, because the LOS is an objective endpoint that cannot be influenced by the patient. Physician blinding is not possible because they perform the surgery.

Patient pathway

All the patients in the trial will go through as depicted in the flowchart (Fig. 2).

Statistical methods

Each patient’s allocation to the analysed population will be defined prior to the analysis and will be documented. In the full analysis set, patients will be analysed as randomised according to the intention-to-treat principle. The intention-to-treat principle implies that the analysis includes all randomised patients. The per protocol analysis set will include all patients without major protocol deviation. Deviations from the protocol will be assessed as major or minor, and patients with major deviations from the protocol will be excluded from the per protocol analysis. The safety analysis set will analyse patients according to the treatment.

The null hypothesis assumes that LOS and post-operative complications are equal in both groups. A binary logistic regression will be used to compare LOS between groups while adjusting for other factors.

Data will be analysed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and expressed as mean ± SD. LOS in the FTS and traditional groups will be compared and analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal distribution). NRS2002 scores between the two groups will be analysed using Wilcoxon’s test (non-normal distribution) or Student’s t test (normal distribution). The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test will be used to analyse the categorical secondary endpoints (complications). P < 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Discussion

FTS has been adopted by most surgical specialties worldwide; however, few studies have assessed FTS in gynaecological malignant surgery [22], and there are currently no randomised controlled trials to support or refute this approach [11]. To our knowledge, no consensus guidelines have been developed for gynaecological oncological surgery although surgeons have attempted to introduce slightly modified FTS programmes for patients undergoing such surgery [3, 11, 12].

Widespread education is needed to improve the rate of implementation of FTS. There are several possible reasons for the lack of implementation including a lack of collaboration within surgical teams and a lack of awareness of or failure to accept and adopt evidence-based findings [8, 9, 23]. Close cooperation between the surgical, anaesthestic, and nursing staff is essential, and the importance of cooperation cannot be overestimated as practice using FTS is needed to achieve further developments in surgical care and post-operative recovery [24, 25]. Fast-track regimens have been well evaluated, generally, regarding medical complications, and they appear to be safe [26].

The aim of this study is to compare LOS and to analyse post-operative complications after major gynaecological or gynaecological oncological surgery. This trial may reveal whether FTS results in early hospital discharge and low complication rates after gynaecological surgery.

Trial status

At the time of writing, we are about to enrol patients, and the anticipated study completion date is May 2017.

Abbreviations

- APACHE II score:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- FTS:

-

fast-track surgery

- LOS:

-

postoperative length of hospitalisation

- PONV:

-

postoperative nausea and vomiting

References

Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Jensen P, Crawford ME, Kehlet H. Recovery after laparoscopic colonic surgery with epidural analgesia, and early oral nutrition and mobilisation. Lancet. 1995;345:763–4.

Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248:189–98.

Acheson N, Crawford R. The impact of mode of anaesthesia on postoperative recovery from fast-track abdominal hysterectomy: a randomised clinical trial. BJOG. 2011;118:271–3.

Yoong W, Sivashanmugarajan V, Relph S, Bell A, Fajemirokun E, Davies T, et al. Can enhanced recovery pathways improve outcomes of vaginal hysterectomy? Cohort control study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:83–9.

Carter J, Szabo R, Sim WW, Pather S, Philp S, Nattress K, et al. Fast track surgery: a clinical audit. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:159–63.

Kehlet H. Fast-track surgery-an update on physiological care principles to enhance recovery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:585–90.

Verheijen PM, Vd Ven AW, Davids PH, Vd Wall BJ, Pronk A. Feasibility of enhanced recovery programme in various patient groups. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:507–11.

Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to postoperative recovery. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:355–8.

Kehlet H. Fast-track colorectal surgery. Lancet. 2008;371:791–3.

Philp S, Carter J, Pather S, Barnett C, D'Abrew N, White K. Patients’ satisfaction with fast-track surgery in gynaecological oncology. Eur J Cancer Care. 2015;24:567–73.

Lu D, Wang X, Shi G. Perioperative enhanced recovery programmes for gynaecological cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD008239.

Lv D, Wang X, Shi G. Perioperative enhanced recovery programmes for gynaecological cancer patients. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2010:CD008239.

Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630–41.

Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, Revhaug A, Dejong CH, Lassen K, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24:466–77.

Pruthi RS, Nielsen M, Smith A, Nix J, Schultz H, Wallen EM. Fast track program in patients undergoing radical cystectomy: results in 362 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:93–9.

Carter J. Fast-track surgery in gynaecology and gynaecologic oncology: a review of a rolling clinical audit. ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:368014.

Lin YS. Preliminary results of laparoscopic modified radical hysterectomy in early invasive cervical cancer. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:80–4.

Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, Schafer M, Mariette C, Braga M, et al. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(R)) Society recommendations. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1209–29.

Williamsson C, Karlsson N, Sturesson C, Lindell G, Andersson R, Tingstedt B. Impact of a fast-track surgery programme for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1133–41.

Bona S, Molteni M, Rosati R, Elmore U, Bagnoli P, Monzani R, et al. Introducing an enhanced recovery after surgery program in colorectal surgery: a single center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17578–87.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Consort G. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657–62.

Marx C, Rasmussen T, Jakobsen DH, Ottosen C, Lundvall L, Ottesen B, et al. The effect of accelerated rehabilitation on recovery after surgery for ovarian malignancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:488–92.

Polle SW, Wind J, Fuhring JW, Hofland J, Gouma DJ, Bemelman WA. Implementation of a fast-track perioperative care program: what are the difficulties? Dig Surg. 2007;24:441–9.

Kranke P, Redel A, Schuster F, Muellenbach R, Eberhart LH. Pharmacological interventions and concepts of fast-track perioperative medical care for enhanced recovery programs. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1541–64.

Sjetne IS, Krogstad U, Odegard S, Engh ME. Improving quality by introducing enhanced recovery after surgery in a gynaecological department: consequences for ward nursing practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:236–40.

Wodlin NB, Nilsson L. The development of fast-track principles in gynecological surgery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:17–27.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Tan Chunlu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China, for consultation and inspiration.

Funding

Funding from the Sichuan Province health department medical key subject projects in Sichuan Province.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

LC conceived and designed the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. YS participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. GZ participated in study design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Once the patients are registered into the group, we use a number to represent the names of patients, and we will not publish data to protect the privacy of patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The independent medical ethics committee of Sichuan Cancer Hospital has approved this trial protocol, with the approval number: SCCHEC20160001. All the procedures of this study are under the oversight of the Chinese Ministry of Health

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, L., Shi, Y. & Zhang, G. Fast-track surgery after gynaecological oncological surgery: study protocol for a prospective randomised controlled trial. Trials 17, 597 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1688-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1688-3