Abstract

Background

Several prediction models of survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) have been published, but no overview of model performance and external validation exists. We performed a systematic review of the available prognostic models for outcome prediction of attempted resuscitation for IHCA using pre-arrest factors to enhance clinical decision-making through improved outcome prediction.

Methods

This systematic review followed the CHARMS and PRISMA guidelines. Medline, Embase, Web of Science were searched up to October 2021. Studies developing, updating or validating a prediction model with pre-arrest factors for any potential clinical outcome of attempted resuscitation for IHCA were included. Studies were appraised critically according to the PROBAST checklist. A random-effects meta-analysis was performed to pool AUROC values of externally validated models.

Results

Out of 2678 initial articles screened, 33 studies were included in this systematic review: 16 model development studies, 5 model updating studies and 12 model validation studies. The most frequently included pre-arrest factors included age, functional status, (metastatic) malignancy, heart disease, cerebrovascular events, respiratory, renal or hepatic insufficiency, hypotension and sepsis. Only six of the developed models have been independently validated in external populations. The GO-FAR score showed the best performance with a pooled AUROC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.69–0.85), versus 0.59 (95%CI 0.50–0.68) for the PAM and 0.62 (95% CI 0.49–0.74) for the PAR.

Conclusions

Several prognostic models for clinical outcome after attempted resuscitation for IHCA have been published. Most have a moderate risk of bias and have not been validated externally. The GO-FAR score showed the most acceptable performance. Future research should focus on updating existing models for use in clinical settings, specifically pre-arrest counselling.

Systematic review registration PROSPERO CRD42021269235. Registered 21 July 2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Advance care directives are becoming increasingly important in modern day medical practice. The possibility of successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in case of cardiac arrest is the quintessential directive to discuss. Expected prognosis after attempted CPR for in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) is an increasingly important part of the dialogue. Providing adequate guidance can be challenging, especially as patients tend to overestimate their likelihood of survival [1]. Even though the likelihood of survival and the chance at good neurological outcome after IHCA remains poor [2]. Ideally, clinicians would be able to identify both patients who have a good chance at qualitative survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation, as well as patients with a low chance of survival, in whom futile resuscitation attempts could be avoided.

Compared to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), there is limited data on outcome after IHCA [3]. Although evidence from OHCA is often extrapolated to IHCA, the epidemiology is different and the determinants of survival and outcome differ accordingly [4]. There is a need for prognostication tools to guide clinicians in decision-making and counselling of patients regarding IHCA. Although several significant peri-arrest prognostic factors for IHCA have been identified, patients and clinicians must rely on pre-arrest factors to establish a CPR-directive [5].

Several risk models were published over the years addressing this clinical dilemma. However, there is still little evidence supporting clinical decision-making [4] and no model has up to now been implemented in clinical practice. An overview of the developed prognostic tools has recently been published, however the focus lay on establishing diagnostic accuracy [6]. The aim of this study was to summarize and appraise prediction models for any clinical outcome after attempted CPR for IHCA using pre-arrest variables, to assess the extent of validation in external populations, and to perform a meta-analysis of the performance of the prognostic models. Clinicians could thus improve the prediction of outcome after IHCA in order to better inform their patients and enhance clinical decision-making.

Methods

This systematic review was designed according to the Checklist for critical Appraisal and data extraction for systematic Reviews of prediction Modelling Studies (CHARMS) and the guidance as described by Debray et al. [7, 8] A protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO (CRD42021269235). Data reporting and review are consistent with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [9]. The review question was formulated using the PICOTS scheme (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Timing and Setting) (Additional file 1: Appendix, Table S1).

Literature search

A systematic search in MEDLINE was performed via PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library for studies published from inception to 22-10-2021. An experienced librarian assisted in developing the search strategy, which included synonyms for [in-hospital cardiac arrest], combined with [prognostic model/prognosis/prediction/outcome assessment]. (Additional file 1: Appendix) The recommendations by Geersing et al. [10] regarding search filters specifically for finding prediction model studies for systematic reviews were followed, as well as those by Bramer et al. using single paragraph searches [11]. Two authors (CGvR, MS) independently screened titles/abstracts and full text articles and discrepancies were resolved by a third author (SH). References of each eligible article were hand searched for potential further inclusion.

Selection criteria

Studies specifically developing, validating and/or updating a multivariable prognostic model for any clinical outcome after attempted resuscitation for IHCA were included. A study was considered eligible following the definition of prognostic model studies as proposed by the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction models for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement [12]. Eligible studies should specifically report the development, update or recalibration, or external validation of prognostic models to predict outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest using pre-arrest factors and report model performance measures. No language restrictions were imposed.

Outcome assessment

Eligible outcomes were any possible clinical outcome after IHCA, such as the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival to discharge (or longer term survival) and neurological outcome (Cognitive Performance Category: CPC). Studies only including peri-arrest factors were excluded, as these prognostic factors are not available at the time of advance care planning. Studies exclusively describing data of patients after ROSC or studies of mixed OHCA/IHCA populations without separate reporting for IHCA-patients were also excluded.

Definitions and terminology

A prognostic model was defined as ‘a formal combination of multiple prognostic factors from which risks of a specific end point can be calculated for individual patients’ [13]. A good clinical prediction model should discriminate between patients who do and do not experience a specific event (discrimination), make accurate predictions (calibration) and perform well across different patient populations (generalisability) [14, 15]. Discrimination is often expressed by the concordance statistic (C-statistic)—the chance that a randomly selected patient who experiences an event has a higher score in the model than a random patient who does not. For binary outcomes, the C-statistic is equal to the area under the operating receiver curve (AUC). Calibration compares the predicted probability of survival with actual survival [16]. It is often visualised with a calibration plot and/ or goodness-of-fit (GOF) as quantified by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Other measures of model performance are sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value, accuracy, R2-statistic and Brier score.

Data extraction

A standardised form following the CHARMS checklist was developed in which two authors independently extracted data (CGvR, MS) [7]. Articles were categorised into development, updating/recalibration and validation subgroups. For all eligible articles, the following information was extracted: first author and year of publication, model name, study population, sample size, source of data (i.e. study design, date of enrolment), number of centres, countries of inclusion, predicted outcome, factors in the model, model performance and information on validation. For development/update studies, model development method, number of prognostic factors screened and final model presentation were collected. Separate individual prognostic factors of the models were tabulated.

Statistical analysis

For prediction models that had been externally validated in multiple studies, a random-effect meta-analysis was performed of the reported AUC’s to yield a pooled AUC for each prediction model [8]. 95% confidence intervals (CI) and (approximate) 95% prediction intervals (PI) were calculated to quantify uncertainty and the presence of between-study heterogeneity. Analyses were performed in R version 4.2.1 using the package metamisc.

Quality assessment

The Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) was used to apply the risk of bias assessment of the studies developing or validating prognostic models [17]. Assessment of methodological quality was done separately by two authors (CGvR, MS).

Results

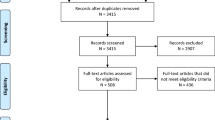

A total of 2678 studies were screened (Fig. 1). Flow diagram of literature search and included studies.) and 33 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis of this systematic review: 16 model development studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], five model updating studies [34,35,36,37,38] and 12 model validation studies [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] (Tables 1, 2 and 4). All studies included patients that received CPR for IHCA. In five studies [20, 21, 25, 26, 31], multiple models were developed resulting in a total of 22 developed models in 16 studies. Of these, seven studies reported (internal) validation of the developed model and three of the five model updating studies reported validation in the original paper (Table 2). Most models were developed or updated using registries as source of data (9/21 studies) or data from retrospective cohorts (7/21 studies). Three studies used a prospective cohort, and in two studies, the source of data was not mentioned (Table 1).

Model development and updating studies

The most frequently predicted outcome was survival to discharge (11 studies), followed by ROSC (8 studies), as shown in Table 1. Survival to discharge with a CPC of 1 (2 studies) [21, 22] or ≤ 2 (3 studies) [34,35,36] was also reported as predicted outcome. Two studies included 3-months survival in their outcomes [25, 32]. Sample size varied from 122 to 92.706 patients. The model updating studies either updated the Good Outcome Following Attempted Resuscitation (GO-FAR) Score (n = 3) [34,35,36] or the Pre-Arrest Morbidity (PAM) Index (n = 2) [37, 38].

Of the model development studies, 10 included pre- and intra-arrest factors and six exclusively pre-arrest factors (Table 2). All model updating studies only included pre-arrest factors, according to the models they were based on. A tabular overview is provided of the most frequently included pre-arrest factors affecting clinical outcome after attempted resuscitation: age, dependent functional status, (metastatic) malignancy, heart disease, cerebrovascular event, respiratory, renal or hepatic insufficiency, hypotension and sepsis (Table 3) (a full overview of the parameters per model is included in the Additional file 1: Appendix).

Half of the developed/updated models were validated in the same paper either by split-sample (internal) validation [19, 22,23,24, 35] or temporal (external) validation [20, 21, 28, 34]. In one study, a bootstrapping technique was used [36]. For the remaining 11 studies, no internal validation or recalibration had taken place [18, 25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33, 37, 38].

Formally, part of the exclusion criteria was the absence of performance measures, but as the Modified PAM Index (MPI) [37] and Prognosis After Resuscitation (PAR) [38] are frequently validated externally, these studies were included with a disclaimer to the overview for this purpose.

Model validation studies

In the 12 model validation studies, a total of seven risk models were independently validated in external populations (Table 4): the GO-FAR score [22], the PAM Index [32], the PAR score [38], the MPI [37], two classification and regression tree models (CARTI and CARTII) [21] and the APACHE III score [47]. The most frequently externally validated models are the PAM (n = 6) [45,46,47,48,49,50], GO-FAR (n = 5) [39,40,41,42, 44], and PAR (n = 5) [45,46,47,48, 50]. The source of data was most frequently a retrospective cohort (n = 10) and twice [40, 42] registry data were used. Sample size varied from 86 to 62.131 patients. In six instances, the validation study was fully independent, meaning the authors of initial score were not implicated in the validation study [39, 41, 45, 46, 49, 50]. There does not seem to be a difference between reported validation performance of the fully independent validation studies and the other external validation studies. Calibration performance was reported in two studies [40, 42]. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve estimates was calculated in 10 validation studies.

Meta-analysis

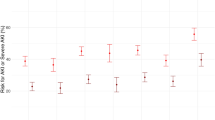

It was possible to calculate a pooled performance of the GO-FAR [39,40,41,42, 44], PAM [45, 47, 48, 50] and PAR [45, 48, 50, 51] scores (Fig. 2. Forest plots of c-statistics in external validation studies.). The GO-FAR score showed the best performance with a pooled AUROC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.69–0.85), versus 0.59 (95%CI 0.50–0.68) for the PAM and 0.62 (95%CI 0.49–0.74) for the PAR.

PROBAST

The assessment of quality with the PROBAST tool showed most risk of bias was present in the ‘analysis’ domain (full assessment in the Additional file 1: Appendix): the number of participants was not always satisfactory, and frequently the way in which missing data were handled was not reported.

Discussion

This systematic review describes prognostic models that use pre-arrest factors to predict outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrest. A comprehensive overview of developed, updated and validated models is presented. Using the best available evidence, i.e. the best performing model, could aid patients and clinicians in making an informed decision whether to attempt or refrain from CPR. Only six models have been validated in external populations. Of these, the GO-FAR score shows the most acceptable performance.

Model development and updating

This systematic review shows that there has been a plethora of prognostic models developed in recent years to predict outcome after IHCA. A total of 27 different prognostic models were published using pre-arrest factors to predict any clinical outcome after IHCA. Approximately half use pre- and intra-arrest factors and the remaining half exclusively pre-arrest factors, which are the models would be more useful in a clinical setting. However, the time at which the factors are assessed often differs from the moment at which the model would be used; as is illustrated by the validation study of the GO-FAR score from Rubins et al. [41]. The authors found the lowest AUC of the GO-FAR score when using it with admission factors, instead of data collected close to the IHCA, which is to be expected as the score was not developed for this moment. However, this demonstrates a potential pitfall of the prognostic models if used in clinical practice. The clinical course of a patient admitted to the hospital is a dynamic process, which in an ideal situation the models would reflect: initially only including pre-arrest factors known at admission and gradually incorporating peri-arrest factors as the clinical situation evolves. A potential problem of prognostic models including both pre-arrest factors and peri-arrest factors is that the peri-arrest factors carry a lot of weight in the model but they are not known at the time of initial counselling. Their importance becomes evident in later clinical decision-making, when deciding whether to (dis)continue a resuscitation attempt. The impact of peri-arrest variables on outcome should be reflected in decision models for termination of CPR, whereas the pre-arrest variables studied in this review should allow for better patient counselling on advance care directives.

As Lauridsen et al. rightfully note, in a recent review of test accuracy studies for IHCA prognosis, there is a need for models that aid in prognostication at an early stage of hospital admission, so that patients (and/or family) can be properly informed. They concluded that no score was sufficiently reliable to support its use in clinical practice. Our study provides a comprehensive review of model development, updating and validating, rather than just the diagnostic accuracy of the tools where no distinction between model development and validation is made [6]. We have critically appraised the methodology behind each model using the PROBAST—as is appropriate in this instance—and have managed to perform a meta-analysis of the models’ performances, using methodological guidance on meta-analysis of prediction model performance [8]. We did specifically not include Early Warning Scores, as they are comprised of physiological parameters that are not available at the time on counselling and are used to estimate the risk of deterioration in hospitalised patients rather than the prognosis after IHCA. They proved to be highly inaccurate for prediction of patient survival. Excluding the studies investigating Early Warning Scores, Lauridsen et al. included 20 studies, whereas this systematic review includes 33 studies maybe due to a search strategy more specific for a systematic review of prediction models [10].

Age was included in almost all models as a prognostic factor for outcome after IHCA. Dependent functional status was also a frequently included factor, as were comorbidities (metastatic) malignancy, renal insufficiency and the presence of sepsis. This corresponds with findings of a recent systematic review evaluating the association of single pre-arrest and intra-arrest factors with survival after IHCA, where the pre-arrest factors age, active malignancy and chronic kidney disease were all independently associated with reduced survival [52]. Male sex was also found to be an independent prognostic factor, but it was only in three of the models included in this systematic review. Frailty has recently been found to be a robust prognostic factor for in-hospital mortality after IHCA, which is reflected in this study by dependent functional status or admission from a nursing facility being frequently included prognostic factors [53]. It is however debateable whether frailty and functional dependence are the same thing. This was recently demonstrated in an observational study, where it was found that moderately frail adults demonstrate heterogeneity in functional status [54].

A wide diversity of predicted outcomes is present in the included models, ranging from the occurrence of ROSC to survival to discharge with a good neurological outcome. And although CPC is not a patient-centred outcome measure, it does provide an extra dimension over survival. Given that the GO-FAR performance is still better than other models, future research should attempt to correlate this model’s variables to health-related quality of life (HRQoL). And as previously argued by Haywood et al., all future cardiac arrest research should use uniform reporting of long-term outcomes and HRQoL to allow for better comparison between studies and represent more clinically relevant outcomes [55,56,57].

Model validation

To maximize the potential and clinical usefulness of prognostic models, they must be rigorously developed and—internally and externally—validated, and their impact on clinical practice and patient outcomes must be evaluated. Model development studies should adjust for overfitting by performing internal validation and recalibration. Several techniques for internal validation (reproducibility) are used and include apparent validation (development and validation in the same population), split-sample validation (random division of data in training and test sets) and bootstrapping (random samples of the same size are drawn with replacement). Only half of the studies in this systematic review which developed scores engaged in some form of (mainly internal and split-sample) validation.

However, no score should be applied in clinical settings unless it has been externally validated. External validation (generalisability) of a model can be performed via geographical or temporal validation or a fully independent validation (with other researchers at another centre) [14]. Only six models were subsequently validated in external populations and only a minority of the models assessed calibration or mention recalibration of the presented model. This could mean an overall overestimation of the performance of the other reported prognostic models. Performance is easily overestimated when there is only apparent validation. Therefore, external validation studies are needed to ensure the generalisability of a prognostic model for medical practice [58]. Moreover, only a minority of the models assessed calibration or mention recalibration of the presented model.

Based on the prognostic models identified through this systematic review, the GO-FAR score has the best performance when validated in external populations and is at this time the most robust and tested model. The performance of the PAM, PAR and MPI in external validation studies limits its consideration for clinical use.

As for generalisability; models were predominantly developed in the USA (using GWTG Registry data) and the UK. Several external validation studies were performed in Sweden in the same relatively small retrospective cohort. This emphasises a need for external model validation and updating in different populations, as many countries are not represented in the current body of literature and important cultural differences play an important role in the installing of advance care directives [59].

Strengths and limitations

This study contains a comprehensive search and extensive analysis using current guidelines for reviewing and assessing bias of prediction model studies [7, 17]. Methodological assessment revealed that the most frequent risk of bias was introduced in the domains source of data, sample size, number of outcomes and analysis (Additional file 1: Appendix.) Limitations pertain mainly to design of the included studies. Only two models were developed with prospective collected data, as is reported to be the superior source of data for the development of prognostic models [13, 17]. Most models were developed using registry data or relatively small retrospective cohorts. Another limitation of this study includes low sensitivity of the search, due to a lack of search terms and indexing for prognostic model studies [10].

Methodological recommendations

An important caveat in interpreting these results and implementing them in practice becomes apparent when examining the prognostic models as the time at which the factors are assessed often differs from the moment at which the model would be used in a clinical setting. A prognostic model meant to be used before starting CPR (at hospital admission, or even prior to that moment) might be more practical and better reflect the moment when the decision-making in advance care planning is taking place and when such a model could be most helpful.

Imputation techniques should be used when data are missing and the full equation of the prognostic model should be presented to allow for external validation and updating by independent research teams and this should be performed in large prospective cohorts. Calibration is an important aspect of performance and should be assessed in future studies, as poorly calibrated models can be unreliable even with good discrimination [16].

There seems to be a gap between the development of prognostic models and the researching of their possible effect on clinical decision-making and maybe even on patient outcomes. Furthermore, clinicians may be eschewing the use of scores due to lack of clear guidance on which score(s) to use, barriers to practical use, or they may find the utility of the scores limited in clinical practice. In spite of the prevalence of risk models, it is known few models have been validated, and even fewer are used regularly in clinical settings [58, 60]. Future research should focus on updating and validating existing prediction models in large external populations, rather than developing new models. After extensive external validation studies of prognostic models, implementation studies are needed to assess their influence in clinical practice [61].

Conclusions

Several prediction models for clinical outcome after attempted resuscitation for IHCA have been published, most have a moderate risk of bias and have not been validated externally. The GO-FAR-score is the only prognostic model included in multiple external validation studies with a decent performance. Future research should focus on updating existing models in large external populations and on their influence on clinical decision-making.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used for the meta-analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, all other data generated of analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

References

Kaldjian LC, Erekson ZD, Haberle TH, Curtis AE, Shinkunas LA, Cannon KT, et al. Code status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adults. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):338–42.

Schluep M, Gravesteijn BY, Stolker RJ, Endeman H, Hoeks SE. One-year survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2018;132:90–100.

Sinha SS, Sukul D, Lazarus JJ, Polavarapu V, Chan PS, Neumar RW, et al. Identifying important gaps in randomized controlled trials of adult cardiac arrest treatments: a systematic review of the published literature. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(6):749–56.

Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-hospital cardiac arrest: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(12):1200–10.

Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, Rochwerg B, Taljaard M, Vaillancourt C, et al. Pre-arrest and intra-arrest prognostic factors associated with survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l6373.

Lauridsen KG, Djärv T, Breckwoldt J, Tjissen JA, Couper K, Greif R, et al. Pre-arrest prediction of survival following in-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Resuscitation. 2022;179:141–51.

Moons KG, de Groot JA, Bouwmeester W, Vergouwe Y, Mallett S, Altman DG, et al. Critical appraisal and data extraction for systematic reviews of prediction modelling studies: the CHARMS checklist. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10):e1001744.

Debray TP, Damen JA, Snell KI, Ensor J, Hooft L, Reitsma JB, et al. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction model performance. BMJ. 2017;356:i6460.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65-94.

Geersing GJ, Bouwmeester W, Zuithoff P, Spijker R, Leeflang M, Moons KG. Search filters for finding prognostic and diagnostic prediction studies in medline to enhance systematic reviews. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e32844.

Bramer WA-O, de Jonge GB, Rethlefsen MA-O, Mast F, Kleijnen J. A systematic approach to searching: an efficient and complete method to develop literature searches. J Med Libr Assoc: JMLA. 2018;106(4):531.

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Br J Surg. 2015;102(3):148–58.

Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, Hayden JA, Perel P, Schroter S, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 3: prognostic model research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(2):e1001381.

Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KG. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. BMJ. 2009;338:b605.

Royston P, Moons KG, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ. 2009;338:b604.

Van Calster B, McLernon DJ, van Smeden M, Wynants L, Steyerberg EW, Topic Group ‘Evaluating diagnostic t, et al. Calibration: the Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):230.

Wolff RF, Moons KGM, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood M, Collins GS, et al. PROBAST: a tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(1):51–8.

Swindell WR, Gibson CG. A simple ABCD score to stratify patients with respect to the probability of survival following in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Commun Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11(3):334–42.

Chan PS, Tang Y. Risk-standardizing rates of return of spontaneous circulation for in-hospital cardiac arrest to facilitate hospital comparisons. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(7):e014837.

Harrison DA, Patel K, Nixon E, Soar J, Smith GB, Gwinnutt C, et al. Development and validation of risk models to predict outcomes following in-hospital cardiac arrest attended by a hospital-based resuscitation team. Resuscitation. 2014;85(8):993–1000.

Ebell MH, Afonso AM, Geocadin RG. Prediction of survival to discharge following cardiopulmonary resuscitation using classification and regression trees*. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):2688–97.

Ebell MH, Jang W, Shen Y, Geocadin RG. Development and validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation (GO-FAR) score to predict neurologically intact survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1872–8.

Chan PS, Berg RA, Spertus JA, Schwamm LH, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC, et al. Risk-standardizing survival for in-hospital cardiac arrest to facilitate hospital comparisons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(7):601–9.

Larkin GL, Copes WS, Nathanson BH, Kaye W. Pre-resuscitation factors associated with mortality in 49,130 cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the national registry for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81(3):302–11.

Danciu SC, Klein L, Hosseini MM, Ibrahim L, Coyle BW, Kehoe RF. A predictive model for survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitation. 2004;62(1):35–42.

Cooper S, Evans C. Resuscitation predictor scoring scale for inhospital cardiac arrests. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(1):6–9.

Ambery P, King B, Bannerjee M. Does concurrent or previous illness accurately predict cardiac arrest survival? Resuscitation. 2000;47(3):267–71.

Dodek PM, Wiggs BR. Logistic regression model to predict outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest: validation, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity. Resuscitation. 1998;36(3):201–8.

Ebell MH. Artificial neural networks for predicting failure to survive following in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J FAM PRACT. 1993;36(3):297–303.

Lawrence ME, Price L, Riggs M. Inpatient cardiopulmonary resuscitation: is survival prediction possible? South Med J. 1991;84(12):1462–6.

Marwick TH, Case CC, Siskind V, Woodhouse SP. Prediction of survival from resuscitation: a prognostic index derived from multivariate logistic model analysis. Resuscitation. 1991;22(2):129–37.

George AL Jr, Folk Iii BP, Crecelius PL, Campbell WB. Pre-arrest morbidity and other correlates of survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Am J Med. 1989;87(1):28–34.

Burns R, Graney MJ, Nichols LO. Prediction of in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(6):1318–21.

Hong SI, Kim YJ, Cho YJ, Huh JW, Hong SB, Kim WY. Predictive value of pre-arrest albumin level with GO-FAR score in patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10631.

George N, Thai TN, Chan PS, Ebell MH. Predicting the probability of survival with mild or moderate neurological dysfunction after in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest: the GO-FAR 2 score. Resuscitation. 2020;146:162–9.

Piscator E, Göransson K, Forsberg S, Bottai M, Ebell M, Herlitz J, et al. Prearrest prediction of favourable neurological survival following in-hospital cardiac arrest: the prediction of outcome for in-hospital cardiac arrest (PIHCA) score. Resuscitation. 2019;143:92–9.

Dautzenberg PLBT, Hooyer C, SchonwetterRS DSA. Review; patient related predictors ofcardiopulmonary resuscitation of hospitalised patients. Age Ageing. 1993;22(6):464–75.

Ebell MH. Prearrest predictors of survival following in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 1992;34(5):551–8.

Cho YJ, Kim YJ, Kim MY, Shin YJ, Lee J, Choi E, et al. Validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation (GO-FAR) score in an east Asian population. Resuscitation. 2020;150:36–40.

Thai TN, Ebell MH. Prospective validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation (GO-FAR)score for in-hospital cardiac arrest prognosis. Resuscitation. 2019;140:2–8.

Rubins JB, Kinzie SD, Rubins DM. Predicting outcomes of in-hospital cardiac arrest: retrospective US validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation score. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2530–5.

Piscator E, Göransson K, Bruchfeld S, Hammar U, el Gharbi S, Ebell M, et al. Predicting neurologically intact survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest-external validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation score. Resuscitation. 2018;128:63–9.

Guilbault RWR, Ohlsson MA, Afonso AM, Ebell MH. External validation of two classification and regression tree models to predict the outcome of inpatient cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;32(5):333–8.

Ohlsson MA, Kennedy LM, Ebell MH, Juhlin T, Melander O. Validation of the good outcome following attempted resuscitation score on in-hospital cardiac arrest in southern Sweden. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:294–7.

Ohlsson MA, Kennedy LM, Juhlin T, Melander O. Evaluation of pre-arrest morbidity score and prognosis after resuscitation score and other clinical variables associated with in-hospital cardiac arrest in southern Sweden. Resuscitation. 2014;85(10):1370–4.

Bowker L, Stewart K. Predicting unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): a comparison of three morbidity scores. Resuscitation. 1999;40(2):89–95.

Ebell MH, Kruse JA, Smith M, Novak J, Drader-Wilcox J. Failure of three decision rules to predict the outcome of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med Decis Mak. 1997;17(2):171–7.

O’Keeffe S, Ebell MH. Prediction of failure to survive following in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: comparison of two predictive instruments. Resuscitation. 1994;28(1):21–5.

Cohn EB, Lefevre F, Yarnold PR, Arron MJ, Martin GJ. Predicting survival from in-hospital CPR: meta-analysis and validation of a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):347–53.

Limpawattana P, Suraditnan C, Aungsakul W, Panitchote A, Patjanasoontorn B, Phunmanee A, et al. A comparison of the ability of morbidity scores to predict unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation in thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2018;101(9):1231–6.

Ebell MH, Kruse JA, Smith M, Novak J, Drader-Wilcox J. Failure of three decision rules to predict the outcome of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med Decis Mak. 1997;17(2):171–7.

Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, Rochwerg B, Taljaard M, Vaillancourt C, et al. Pre-arrest and intra-arrest prognostic factors associated with survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6373.

Mowbray FI, Manlongat D, Correia RH, Strum RP, Fernando SM, McIsaac D, et al. Prognostic association of frailty with post-arrest outcomes following cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2021;167:242–50.

Chong E, Chan M, Tan HN, Lim WS. Heterogeneity in functional status among moderately frail older adults: improving predictive performance using a modified approach of subgrouping the clinical frailty scale. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(2):275–84.

Haywood K, Whitehead L, Nadkarni VM, Achana F, Beesems S, Böttiger BW, et al. COSCA (core outcome set for cardiac arrest) in adults: an advisory statement from the international liaison committee on resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2018;127:147–63.

Whitehead L, Perkins GD, Clarey A, Haywood KL. A systematic review of the outcomes reported in cardiac arrest clinical trials: the need for a core outcome set. Resuscitation. 2015;88:150–7.

Elliott VJ, Rodgers DL, Brett SJ. Systematic review of quality of life and other patient-centred outcomes after cardiac arrest survival. Resuscitation. 2011;82(3):247–56.

Moons KG, Kengne AP, Grobbee DE, Royston P, Vergouwe Y, Altman DG, et al. Risk prediction models: II. External validation, model updating, and impact assessment. Heart. 2012;98(9):691–8.

Gibbs AJO, Malyon AC, Fritz ZBM. Themes and variations: an exploratory international investigation into resuscitation decision-making. Resuscitation. 2016;103:75–81.

Wyatt JC, Altman DG. Commentary: prognostic models: clinically useful or quickly forgotten? Br Med J. 1995;311(7019):1539–41.

Reilly BM, Evans AT. Translating clinical research into clinical practice: impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(3):201–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge W. Bramer for helping with the systematic literature search.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in conceptualising the review question. CG and MS screened and included relevant articles. SH performed the meta-analysis. CG was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary materials: search strategy and PROBAST assessment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Grandbois van Ravenhorst, C., Schluep, M., Endeman, H. et al. Prognostic models for outcome prediction following in-hospital cardiac arrest using pre-arrest factors: a systematic review, meta-analysis and critical appraisal. Crit Care 27, 32 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04306-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04306-y