Abstract

Background

Prolonged ventilatory support is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Partial support modes, especially pressure support ventilation, are frequently used in clinical practice but are associated with patient–ventilation asynchrony and deliver fixed levels of assist. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA), a mode of partial ventilatory assist that reduces patient–ventilator asynchrony, may be an alternative for weaning. However, the effects of NAVA on weaning outcomes in clinical practice are unclear.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Medline, and Cochrane Library from 2007 to December 2020. Randomized controlled trials and crossover trials that compared NAVA and other modes were identified in this study. The primary outcome was weaning success which was defined as the absence of ventilatory support for more than 48 h. Summary estimates of effect using odds ratio (OR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes with accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI) were expressed.

Results

Seven studies (n = 693 patients) were included. Regarding the primary outcome, patients weaned with NAVA had a higher success rate compared with other partial support modes (OR = 1.93; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.32; P = 0.02). For the secondary outcomes, NAVA may reduce duration of mechanical ventilation (MD = − 2.63; 95% CI − 4.22 to − 1.03; P = 0.001) and hospital mortality (OR = 0.58; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.84; P = 0.004) and prolongs ventilator-free days (MD = 3.48; 95% CI 0.97 to 6.00; P = 0.007) when compared with other modes.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that the NAVA mode may improve the rate of weaning success compared with other partial support modes for difficult to wean patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mechanical ventilation (MV) remains a lifesaving intervention for patients with respiratory failure of different etiologies, and 20–60% of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) required ventilatory support [1, 2]. While invasive MV maintains the airway, its use over a prolonged period is associated with adverse clinical complications and outcomes [3, 4]. In turn, these complications contribute to weaning failure, duration of intubation, and ICU mortality. Consequently, optimizing strategies for weaning and minimizing the duration of invasive MV have been an important goal to reduce morbidity and mortality [5].

Weaning from MV is an essential and universal process for intubated patients in the ICU—it should be considered as early as possible in the course of MV. Weaning refers to the efficient process of withdrawing ventilator support, including discontinuation of MV and removal of the artificial airway [6]. The transition from controlled MV to spontaneous breathing can be achieved by modes of partial ventilatory assist and may minimize the adverse effects of diaphragm inactivity and excessive sedation [7,8,9]. Pressure support ventilation (PSV) is the most widely used mode of partial assistance. However, the imperfectly set and fixed level of inspiratory support in PSV may increase the risk of over- and/or under-assist ventilatory and may lead to diaphragm weakness or excessive diaphragm work [10]. Not to be ignored is the fact that PSV demonstrates patient–ventilator asynchrony (PVA), which occurs in approximately 25% of patients with invasive MV and is known to be associated with prolonged of duration of MV and increased mortality [11,12,13,14].

Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA) is a mode of partial ventilatory assist in which the timing and intensity of the ventilatory assistance are determined by the electrical activity of the diaphragm (Edi) [15], a measurement of respiratory drive. Hence, NAVA delivers inspiratory pressure in proportion to the patient’s inspiratory effort. Previous studies have shown that NAVA can reduce PVA and lung overdistension [16, 17]. In several studies, NAVA has shown physiological benefits compared to PSV with respect to preferential recruitment of the dependent part of lung [18], improved gas exchange and sleep [19, 20], and less sedation requirements [21]. These findings suggest that NAVA—being more physiological—could optimize weaning. However, the evidence on weaning and clinically relevant outcomes for NAVA is limited.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of NAVA for intubated patients with respiratory failure by measuring weaning success and other clinically relevant outcomes.

Methods

We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement for performing the systematic review and meta-analysis [22]. Our study protocol was registered at PROSPERO with the registration number CRD42021225997.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including those with crossover design. Relevant conference abstracts were considered for inclusion after contacting the authors. Studies were eligible if they (i) included adults (aged 18 years or older) with respiratory failure from various etiologies who received invasive MV for least 24 h, (ii) compared NAVA with partial support modes (PSV, assist/control (A/C), or pressure-regulated volume control (PRVC)), and (iii) included patients who were undergoing weaning trials for liberation from MV. We excluded studies that extubated patients directly to non-invasive ventilation.

The primary outcome was weaning success, which was defined as the absence of the requirement for ventilatory support, without reintubation, a cardiac arrest event, or mortality within 48 h after extubation or withdrawal. The secondary outcomes included duration of MV, ventilator-free days at day 28 (VFDs), ICU mortality, hospital mortality, length of hospital stay (hospital LOS), adverse events, and tracheostomy.

Search strategy

We conducted an electronic search of PubMed, Embase, Medline, and Cochrane Library for all relevant studies from 2007 to December 2020. We restricted the articles to those published in English. The details of the search strategies used for each database are presented in the Additional file 1: Table S1. In addition, we manually retrieved the bibliographies of all relevant studies and reviews to identify potentially eligible studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We merged the search results and removed the duplicate records of the same study. Two authors (XY and XL) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the initial search strategy for potential eligibility and retrieved the potentially relevant studies for full-text review. Data were independently extracted by two authors (XY and YC) using a standardized data collection form. Disagreements were resolved through consensus with a third author (JX).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (XL and YC) assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for RCTs [23] and the checklist proposed by Ding et al. [24] for crossover studies, both independently and in duplicate. Specifically, the methodological quality of crossover studies was assessed with appropriate crossover design, carryover effect, unbiased data, randomized sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other bias. The overall risk of bias was considered to be high if any individual category was high. The overall certainty of evidence for each outcome was assessed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [25]. Disagreements were resolved through a consensus with a third author (JX).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Cochran’s Q test, a Chi-square test, with a threshold P value of less than 0.10 [26]. The impact of heterogeneity on outcomes was assessed using I2 statistic [27]. I2 greater than or equal to 50% was considered as statistically significant heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

The presence of publication bias on the primary outcome was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s test [28].

Data synthesis

For dichotomous variables, the estimated effects were pooled with Mantel–Haenszel method and expressed with the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). For the continuous variables, the estimated effects were pooled with the inverse variance method and expressed with the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. To statistically combine the data from the included studies, the median along with the 25% and 75% percentiles was transformed into means and standard deviation using the method proposed by Liu et al. [29]. The choice between fixed-effect or random-effect models was based on statistical heterogeneity. If P < 0.10 with the Chi-square test or I2 > 50%, a random-effects model was used to pool data; otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used.

Subgroup analysis

For the primary outcome, we conducted subgroup analysis by the weaning state (i.e., simple weaning, difficult weaning, prolonged weaning).

Trial sequential analysis (TSA)

We used TSA to identify the risk of both type 1 and type 2 error due to sparse data and repetitive testing of accumulating data for primary outcome in our meta-analysis [30]. The Lan-DeMets approach was used to estimate the required information size and construct O’Brien–Fleming monitoring boundaries. We defined a statistical significance level of 5%, a power of 80%, and a relative risk reduction of 35%. TSA was conducted by Trial Sequential Analysis software (version 0.9.5.10 Beta 2; Copenhagen Trial Unit, Copenhagen, Denmark).

All statistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Results of the search

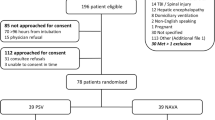

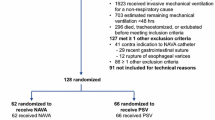

We identified 1678 records in accordance with the search strategy and retrieved the full text of 75 studies for possible eligibility. The flowchart of our search process is presented in Fig. 1. Of the 75 studies, 7 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final quantitative synthesis [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The seven included studies comprised a total of 693 patients. One of them was a published conference abstract [31]. Of note, 4 of the 7 studies were included in the meta-analysis of weaning success [31, 33,34,35].

Included studies

Study characteristics and patient characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. All the included studies were published between 2016 and 2020. Five studies were single-center studies [31,32,33, 35, 37] and 2 were multi-center studies [34, 36]. Among the seven studies, 6 RCTs and 1 crossover trial were identified. Assessment of the risk of bias in included studies is shown in Additional file 1: Figs. S1 and S2. The overall quality of these studies was low–moderate. Blinding of participants and personnel was impossible owing to the essence of study design, but the blinding of outcome assessment was applicable [32]. According to the difficulty and length of weaning process, we divided patients of the included studies into three categories, namely simple weaning, difficult weaning, and prolonged weaning [6]. Two studies included patients who were classified into difficult weaning [31, 35]. COPD patients in one study were assigned to the prolonged weaning group [37]. The remaining four studies included patients with more than one weaning category [32,33,34, 36].

Primary outcome

A total of 4 studies, involving 512 patients, were included in the analysis [31, 33,34,35] for the primary outcome. Two other studies were excluded for lack of data on the weaning success [36, 37]. One crossover trial was excluded due to the potential risk for carryover effect [32]. The meta-analysis using a fixed-effect model showed a statistically significant proportion of patients who received NAVA (217/254) weaned successfully, compared with patients who received other partial support modes (202/258) (OR = 1.93; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.33; P = 0.02) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis was performed to compare the efficiency of NAVA with the weaning categories, and the result showed a statistical difference favoring NAVA (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Among 4 studies including 129 patients who were identified as difficult weaning, there was a significant difference between the patients who underwent NAVA versus other weaning modes, with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.13 to 4.73, P = 0.02).

The certainty of evidence, using the GRADE approach, was moderate (Additional file 1: Table S2). Visual inspection of a funnel plot on weaning success was evaluated and did not suggest the evidence of publication bias (Additional file 1: Fig. S5). TSA suggested the required information size was not reached, but the fact that cumulative z-curve crossed the conventional boundary showed patients undergoing NAVA was more likely to result in successful weaning (Additional file: Fig. S5).

Secondary outcomes

Duration of MV

In 6 studies reporting about 673 patients, 4 studies included the duration of MV from randomization [33,34,35,36] and 2 studies included the duration of MV from intubation [31, 37]. For all 6 studies, we found a statistically significant probability of lower duration of MV supporting patients undergoing NAVA comparing to other partial support modes (MD = − 2.63; 95% CI − 4.22 to − 1.03; P = 0.001), and the heterogeneity was moderate with I2 = 68% (Fig. 3). Furthermore, subgroup analysis showed a statistically significant difference favoring NAVA in duration of MV when described from randomization. The certainty of evidence was moderate due to inconsistency (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Ventilator-free days at day 28

For the 4 studies recruiting 566 patients [34,35,36,37], patients undergoing NAVA had a greater VFDs compared with patients undergoing other partial support modes (MD = 3.48; 95% CI 0.97 to 6.00; P = 0.007) (Fig. 4). The certainty of evidence was moderate due to imprecision (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Hospital mortality

Hospital mortality was evaluated in 5 studies involving 555 patients [31, 33,34,35, 37], and the result demonstrated patients ventilated with NAVA had lower hospital mortality compared to patients ventilated with other partial support modes (OR = 0.58; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.84; P = 0.004) (Fig. 5). The certainty of evidence was moderate due to imprecision (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Other secondary outcomes

There was no statistically significant difference in ICU mortality, hospital LOS, tracheostomy, or adverse events (ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), pneumothorax) (Additional file 1: Fig. S6-S9). The certainty of evidence was moderate due to imprecision (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Discussion

This systematic review identified 7 studies to evaluate the efficacy of NAVA as a weaning mode in intubated patients with previous respiratory failure in terms of the rate of weaning success and other clinically relevant outcomes. The main finding was that, compared with other partial support modes (especially PSV), NAVA was associated with a higher chance of weaning success, lower duration of MV from time of intubation, greater amount of VFDs, and lower hospital mortality. Subgroup analysis suggested that compared with studies involving patients with mixed weaning categories, the benefits of NAVA in terms of weaning success were greater in studies involving patients with difficult weaning.

This systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to evaluate the weaning success in patients undergoing NAVA. Previous physiologic studies have confirmed that NAVA improves patient–ventilator interaction and decreases the occurrence of ventilator under-assist and over-assist [12, 16, 17, 38]. Considering that PVA, a common occurrence in critically ill patients with MV, increases the likelihood of respiratory muscle injury and may be associated with delayed weaning off MV [39], NAVA may be associated with more efficient weaning and has the potential to improve clinical outcomes. However, there is limited evidence on the clinically relevant outcomes for NAVA. Our study demonstrates a biologically plausible association between NAVA and a higher rate of weaning success in intubated patients. However, the efficacy of NAVA in patients with different diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), neuromuscular diseases) was not evaluated in terms of granular data. Additional studies are further needed.

NAVA and proportional assist ventilation (PAV) are both proportional modes of ventilation readily available in clinical practice and have advantages in reducing PVA [12] and providing the potential for both lung and diaphragm-protective ventilation [40]. Regarding proportional modes of ventilation (either NAVA or PAV, or both), a meta-analysis of 15 studies has shown that proportional modes, when compared with PSV, were associated with a reduction in weaning failure and duration of MV. Reduced duration of mechanical ventilation was found with PAV but not with NAVA [41]. However, our results showed that NAVA was associated with a higher rate of weaning success and lower duration of MV. The potential mechanisms for this effect were speculated as follows: First, PVA is common during MV but underdiagnosed. Previous studies have suggested PVA might lead to lung and vascular injury and thereby was associated with poor clinical outcomes including prolongation of mechanical ventilation [13], increased mortality [42], ICU and hospital stay [43], discomfort [44], and sleep disorders [45]. Recently, most physiological studies have demonstrated that NAVA is associated with a lower asynchrony index (AI) and lower severe asynchrony compared to PSV [12, 45, 46]. Therefore, NAVA may potentially result in weaning success on account of reducing the occurrence of PVA. Second, diaphragm function is a crucial determinant of patients’ outcomes. Mounting evidence demonstrates that ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction (VIDD) is significantly associated with difficult weaning and poor clinical outcomes [47,48,49]. NAVA achieves assisted ventilation by monitoring the electrical activity of diaphragm and reduces VIDD [12, 50]. Worth mentioning, NAVA can prevent over-assistance with the fact that Edi will not disappear completely at high levels of assist because it is required to run the ventilator. NAVA may, therefore, facilitate weaning from MV by preventing or reversing diaphragmatic atrophy [50]. Third, NAVA is considered to reproduce the variability of the neural respiratory drive [40]. Thus, preservation of respiratory variability during NAVA is another potential mechanism for lung protective ventilation and may be an explanation for our results. Fourth, preferential lung recruitment in ARDS is one features of NAVA. Widing et al. [18] found NAVA could decrease recruitment/derecruitment in the ARDS model. [Recruitment/derecruitment can lead to ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).] The study conducted by Blankman et al. [51] to identify the effect of varying levels of assist during PSV and NAVA showed that NAVA had a better promoting effect on the ventilation of the dependent lung region and less over-assistance. Hence, it could be suggested that NAVA shows beneficial effects on weaning by reducing VILI. Fifth, sleep quality may play an important role in the weaning success. Sleep deprivation may be a risk factor for weaning failure due to decreased respiratory muscle endurance and increased incidence of delirium [6, 43]. Furthermore, previous studies found that weaning time was longer in patients with sleep loss [52]. In the Delisle et al. study, the benefit of improved sleep quality was even more pronounced in NAVA than PSV [20]. Sixth, NAVA has the benefit of using lower sedative doses in acute respiratory failure [21]. Evidence suggests that sedation worsens outcomes in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation [53]. In addition, long-term sedation may delay liberation from MV and increase the risk of delirium [54, 55].

The differences of underlying weaning status may affect the role of NAVA on weaning success. Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis in terms of the difficulty and length of the weaning process, namely simple weaning, difficult weaning, and prolonged weaning [6]. In our analysis, two studies included patients with difficult weaning, and two studies included patients with mixed weaning categories. Our results showed that NAVA was associated with higher rate of weaning success in patients with difficult weaning. Therefore, it is speculated that NAVA may have a beneficial effect on patients in which the quality of patient–ventilator interactions is essential, such as patients with difficult weaning. Also, the ventilator allowed monitoring of the diaphragmatic electrical activity in NAVA. So, this group of patients may have a higher rate of successful weaning because of less VIDD. (By monitoring Edi, it is possible to ensure appropriate levels of diaphragm activity and avoids disuse atrophy.)

This meta-analysis also demonstrated that NAVA was associated with a shorter duration of MV and greater VFDs at day 28 compared with other partial support modes. The finding is important as these may facilitate patients’ liberation from MV and discharge from hospital. Previous studies have suggested that severe PVA was associated with worsened outcomes [11, 12, 17]. Therefore, NAVA is speculated to improve these clinically relevant outcomes by reducing PVA, but there is limited evidence to confirm this. In one meta-analysis performed by Chen et al., patients undergoing NAVA had a shorter duration of ventilation than PSV [56]. But in their manuscript, only two studies were included, and the duration of ventilation was not defined clearly.

Our findings also demonstrated a significant association with lower hospital mortality but not ICU mortality and hospital LOS with the use of NAVA compared with other partial support modes. Although it is possible that a higher weaning success may reduce all-cause mortality and shorten the hospital LOS, few data have confirmed this assumption. Potential explanations for these findings may include concomitant complications and different causes of acute respiratory failure among the included patients. Our study also indicated that no significant differences were observed between NAVA and other partial support modes on reduced adverse events (VAP, pneumothorax) and tracheostomy. The possible explanation for the results could be very limited data in included studies. So, larger RCTs are needed to confirm these results.

Our meta-analysis suggests the beneficial effect of NAVA as an alternative to wean, and as well, that NAVA may be associated with lower duration of MV from time of randomization, greater VFDs and lower hospital mortality. The results could be expected given the physiological design of the NAVA mode. It is worth noting that NAVA does have limitations. For example, it is not possible to blind the NAVA arm in studies, since the ventilator screen needs to be viewed, and the patient has an Edi catheter. Also, setting the NAVA level is not a “one size fits all” and is patient-specific. Moreover, NAVA may be associated with a higher prevalence of double triggering in several conditions [12, 16]. Therefore, the above should be kept in mind when interpreting our results.

There are several limitations to our meta-analysis. First, the lack of a detailed weaning protocol implementation in included studies is a major source of heterogeneity which may affect our results. In addition, the included studies involved heterogeneous populations and used variable definitions of outcomes (e.g., duration of MV) despite attempts to reduce clinical heterogeneity. Second, one of the included studies is a crossover trial, which is a theoretical risk that the efficacy of NAVA may be overestimated or underestimated compared with that of other partial support modes. Third, all studies in our analysis had a high risk of performance bias because of the inability to blind the investigators to the method of weaning. So, it is possible that the investigators’ decisions and actions may be influenced, resulting in biased estimates of results. Fourth, not all the data on the tracheostomized patients with successful weaning were included. This may affect the results for the primary outcome in our study. Fifth, five included studies are characterized as small studies of which the sample size was less than 100 patients. Hence, the study effect bias may exist in our results. Further RCTs should be performed to confirm our results.

Conclusions

Ventilation with the NAVA mode may improve the rate of weaning success compared to other partial support modes for difficult to wean patients. The evaluation of duration of MV, ventilator-free days at day 28, hospital mortality, and successful extubation were in favor of NAVA.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- NAVA:

-

Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist

- PVA:

-

Patient–ventilator asynchrony

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- PSV:

-

Pressure support ventilation

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- VIDD:

-

Ventilator-induced diaphragm

- VILI:

-

Ventilator-induced lung injury

- Edi:

-

Electrical activity of the diaphragm

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- PRVC:

-

Pressure-regulated volume control

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- LOS:

-

Length of hospital stay

- VFDs:

-

Ventilator-free days

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Rowan KM. Comparison of medical admissions to intensive care units in the United States and United Kingdom. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(12):1666–73.

Metnitz PG, Metnitz B, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Del Sorbo L, Hoermann C, et al. Epidemiology of mechanical ventilation: analysis of the SAPS 3 database. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(5):816–25.

Béduneau G, Pham T, Schortgen F, Piquilloud L, Zogheib E, Jonas M, et al. WIND (Weaning according to a New Definition) Study Group and the REVA (Réseau Européen de Recherche en Ventilation Artificielle) Network: Epidemiology of weaning outcome according to a new definition: the WIND study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(6):772–83.

Peñuelas O, Frutos-Vivar F, Fernández C, Anzueto A, Epstein SK, Apezteguía C, et al. Ventila Group: characteristics and outcomes of ventilated patients according to time to liberation from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(4):430–7.

MacIntyre NR, Cook DJ, Ely EW Jr, Epstein SK, Fink JB, Heffner JE, et al. Evidence based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support. A collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Association for Respiratory Care and the College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001;120(Suppl 6):375S-S395.

Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, Herridge M, Marsh B, Melot C, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Resp J. 2007;29(5):1033–56.

Hudson MB, Smuder AJ, Nelson WB, Bruells CS, Levine S, Powers SK. Both high level pressure support ventilation and controlled mechanical ventilation induce diaphragm dysfunction and atrophy. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1254–60.

Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, Friscia ME, Budak MT, Rothenberg P, et al. Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1327–35.

Haaksma ME, Tuinman PR, Heunks L. Weaning the patient: between protocols and physiology. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27(1):29–36.

Goligher EC, Dres M, Fan E, Rubenfeld GD, Scales DC, Herridge MS, et al. Mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragm atrophy strongly impacts clinical outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(2):204–13.

Murias G, Lucangelo U, Blanch L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22(1):53–9.

Pettenuzzo T, Aoyama H, Englesakis M, Tomlinson G, Fan E. Effect of neurally adjusted ventilatory assist on patient-ventilator interaction in mechanically ventilated adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(7):e602–9.

de Wit M, Miller KB, Green DA, Ostman HE, Gennings C, Epstein SK. Ineffective triggering predicts increased duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2740–5.

Thille AW, Rodriguez P, Cabello B, Lellouche F, Brochard L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during assisted mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(10):1515–22.

Sinderby C, Navalesi P, Beck J, Skrobik Y, Comtois N, Friberg S, et al. Neural control of mechanical ventilation in respiratory failure. Nat Med. 1999;5(12):1433–6.

Schmidt M, Kindler F, Cecchini J, Poitou T, Morawiec E, Persichini R, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist and proportional assist ventilation both improve patient-ventilator interaction. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):56.

Piquilloud L, Vignaux L, Bialais E, Roeseler J, Sottiaux T, Laterre PF, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist improves patient-ventilator interaction. Intensive Care Med. 2010;37(2):263–71.

Widing CH, Pellegrini M, Larsson A, Perchiazzi G. The effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on transpulmonary pressure and recruitment-derecruitment during neurally adjusted ventilator assist: a continuous computed tomography study in an animal model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1392.

Coisel Y, Chanques G, Jung B, Constantin JM, Capdevila X, Matecki S, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in critically ill postoperative patients: a crossover randomized study. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:925–35.

Delisle S, Ouellet P, Bellemare P, Tétrault JP, Arsenault P. Sleep quality in mechanically ventilated patients: comparison between NAVA and PSV modes. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1(1):42.

Vaschetto R, Cammarota G, Colombo D, Longhini F, Grossi F, Giovanniello A, et al. Effects of propofol on patient-ventilator synchrony and interaction during pressure support ventilation and neurally adjusted ventilatory assist. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(1):74–82.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-34.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.0 [updated February 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Ding H, Hu GL, Zheng XY, Chen Q, Threapleton DE, Zhou ZH. The method quality of cross-over studies involved in Cochrane Systematic Reviews. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0120519.

Ryan RHS. How to GRADE the quality of the evidence. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group; 2016. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Accessed April 2019.

Pereira TV, Patsopoulos NA, Salanti G, Ioannidis JP. Critical interpretation of Cochran’s Q test depends on power and prior assumptions about heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):149–61.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–94.

Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(6):1785–805.

Wetterslev J, Jakobsen JC, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis in systematic reviews with meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):39.

Fakher M, Kamal H, Yehia M, Abdelwahab K, Abdelfatah A. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation during SBT in patients with difficult weaning. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(Suppl 3):001668.

Ferreira JC, Diniz-Silva F, Moriya HT, Alencar AM, Amato MBP, Carvalho CRR. Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist (NAVA) or Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV) during spontaneous breathing trials in critically ill patients: a crossover trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):139.

Hadfield DJ, Rose L, Reid F, Cornelius V, Hart N, Finney C, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation: a randomized controlled feasibility trial performed in patients at risk of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):220.

Kacmarek RM, Villar J, Parrilla D, Alba F, Solano R, Liu S, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in acute respiratory failure: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(12):2327–37.

Liu L, Xu X, Sun Q, Yu Y, Xia F, Xie J, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation in diffiult weaning. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1482–93.

Demoule A, Clavel M, Rolland-Debord C, Perbet S, Terzi N, Kouatchet A, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist as an alternative to pressure support ventilation in adults: a French multicentre randomized trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(11):1723–32.

Kuo NY, Tu ML, Hung TY, Liu SF, Chung YH, Lin MC, et al. A randomized clinical trial of neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus conventional weaning mode in patients with COPD and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:945–51.

Doorduin J, Sinderby CA, Beck J, van der Hoeven JG, Heunks LMA. Assisted ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome—lung-distending pressure and patient-ventilator interaction. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(1):181–90.

Rolland-Debord C, Bureau C, Poitou T, Belin L, Clavel M, Perbet S, et al. Prevalence and prognosis impact of patient-ventilator asynchrony in early phase of weaning according to two detection methods. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(6):989–97.

Jonkman AH, Rauseo M, Carteaux G, Telias I, Sklar MC, Heunks L, et al. Proportional modes of ventilation: technology to assist physiology. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(12):2301–13.

Kataoka J, Kuriyama A, Norisue Y, Fujitani S. Proportional modes versus pressure support ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):123.

Blanch L, Villagra A, Sales B, Montanya J, Lucangelo U, Lujan M, et al. Asynchronies during mechanical ventilation are associated with mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(4):633–41.

Bosma K, Ferreyra G, Ambrogio C, Pasero D, Mirabella L, Braghiroli A, et al. Patient-ventilator interaction and sleep in mechanically ventilated patients: pressure support versus proportional assist ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1048–54.

de Haro C, Ochagavia A, López-Aguilar J, Fernandez-Gonzalo S, Navarra-Ventura G, Magrans R, et al. Patient-ventilator asynchronies during mechanical ventilation: current knowledge and research priorities. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(Suppl 1):43.

Terzi N, Pelieu I, Guittet L, Ramakers M, Seguin A, Daubin C, et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in patients recovering spontaneous breathing after acute respiratory distress syndrome: Physiological evaluation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(9):1830–7.

Doorduin J, Sinderby CA, Beck J, van der Hoeven JG, Heunks LM. Assisted ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: lung-distending pressure and patient-ventilator interaction. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(1):181–90.

Dres M, Dubé BP, Mayaux J, Delemazure J, Reuter D, Brochard L, et al. Coexistence and impact of limb muscle and diaphragm weakness at time of liberation from mechanical ventilation in medical intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(1):57–66.

Dubé BP, Dres M, Mayaux J, Demiri S, Similowski T, Demoule A. Ultrasound evaluation of diaphragm function in mechanically ventilated patients: comparison to phrenic stimulation and prognostic implications. Thorax. 2017;72(9):811–8.

Jung B, Moury PH, Mahul M, de Jong A, Galia F, Prades A, et al. Diaphragmatic dysfunction in patients with ICU-acquired weakness and its impact on extubation failure. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):853–61.

Vaporidi K. NAVA and PAV+ for lung and diaphragm protection. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020;26(1):41–6.

Blankman P, Hasan D, van Mourik MS, Gommers D. Ventilation distribution measured with EIT at varying levels of pressure support and Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist in patients with ALI. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(6):1057–62.

Dres M, Younes M, Rittayamai N, Kendzerska T, Telias I, Grieco DL, et al. Sleep and pathological wakefulness at the time of liberation from mechanical ventilation (SLEEWE): A prospective multicenter physiological study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(9):1106–15.

Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126–34.

Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, et al. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):21–6.

Barrientos-Vega R, Mar Sánchez-Soria M, Morales-García C, Robas-Gómez A, Cuena-Boy R, Ayensa-Rincon A. Prolonged sedation of critically ill patients with midazolam or propofol: impact on weaning and costs. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(1):33–40.

Chen C, Wen T, Liao W. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation in patient-ventilator interaction and clinical outcomes: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(16):382.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81870066, 81930058); Clinical Science and Technology Specific Projects of Jiangsu Province (BE2020786, BE2019749); National Science and Technology Major Project (2020ZX09201015); and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20171271). Dr. Sinderby is funded in part by the RS McLaughlin Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XY and XL searched the scientific literature and drafted the manuscript. YC and JX contributed to the conception, design, and data interpretation. XY and LL collected the data and performed statistical analyses. HQ and YY contributed to the conception, design, data interpretation, manuscript revision for critical intellectual content, and supervision of the study. JB and CS participated in data interpretation and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Drs. Beck and Sinderby have made inventions related to neural control of mechanical ventilation that are patented. The patents are assigned to the academic institution(s) where inventions were made. The license for these patents belongs to Maquet Critical Care. Future commercial uses of this technology may provide financial benefit to Dr. Beck and Dr. Sinderby through royalties. Dr Beck and Dr Sinderby each own 50% of Neurovent Research Inc (NVR). NVR is a research and development company that builds the equipment and catheters for research studies. NVR has a consulting agreement with Maquet Critical Care.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The main results of search strategy, GRADE evidence profile, risk of bias, reporting bias, TSA, subgroup analysis, and secondary outcomes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, X., Lu, X., Chao, Y. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist as a weaning mode for adults with invasive mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 25, 222 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03644-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03644-z