Abstract

Background

Hyperglycaemia is associated with adverse outcomes in the intensive care unit, and initial studies suggested outcome benefits of glycaemic control (GC). However, subsequent studies often failed to replicate these results, and they were often unable to achieve consistent, safe control, raising questions about the benefit or harm of GC as well as the nature of the association of glycaemia with mortality and clinical outcomes. In this study, we evaluated if non-survivors are harder to control than survivors and determined if glycaemic outcome is a function of patient condition and eventual outcome or of the glycaemic control provided.

Methods

Clinically validated, model-based, hour-to-hour insulin sensitivity (SI) and its hour-to-hour variability (%ΔSI) were identified over the first 72 h of therapy in 145 patients (119 survivors, 26 non-survivors). In hypothesis testing, we compared distributions of SI and %ΔSI in 6-hourly blocks for survivors and non-survivors. In equivalence testing, we assessed if differences in these distributions, based on blood glucose measurement error, were clinically significant.

Results

SI level was never equivalent between survivors and non-survivors (95% CI of percentage difference in medians outside ±12%). Non-survivors had higher SI, ranging from 9% to 47% higher overall in 6-h blocks, and this difference became statistically significant as glycaemic control progressed. %ΔSI was equivalent between survivors and non-survivors for all 6-hourly blocks (95% CI of difference in medians within ±12%) and decreased in general over time as glycaemic control progressed.

Conclusions

Whereas non-survivors had higher SI levels, variability was equivalent to that of survivors over the first 72 h. These results indicate survivors and non-survivors are equally controllable, given an effective glycaemic control protocol, suggesting that glycaemia level and variability, and thus the association between glycaemia and outcome, are essentially determined by the control provided rather than by underlying patient or metabolic condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rationale

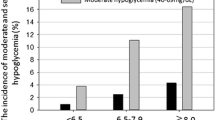

Glycaemic control (GC) in the intensive care unit (ICU) is a controversial subject [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Whereas some studies showed improved mortality with GC within a tight or intermediate range [8,9,10,11,12], several others studies and larger analyses did not reproduce these results [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Increased hypoglycaemia induced by the GC protocol, patient variability and/or protocol compliance further confounds results.

The strong associations of blood glucose (BG) level and/or variability with mortality [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] have been used to make a case for GC. The association of moderate or severe hypoglycaemia with increased mortality [29, 32,33,34] similarly indicates that improved control must be achieved safely, despite high inter- and intra- patient variability [28, 31, 35,36,37,38,39]. The association of high times in intermediate bands with reduced mortality [40,41,42,43,44,45] would indicate that this control quality must be consistent over time and for most (or all) patients, which was achieved in only a few studies considering outcome [8,9,10, 12]. This overall case states that outcomes are driven largely by the quality and consistency of GC.

However, association is not causality. Another, equally valid interpretation of these associations is that non-survivors are harder to control, and thus they have the higher glycaemic levels and variability associated with mortality. Similarly, it may be that patients who die are more variable and are thus more likely, under insulin control, to experience moderate or severe hypoglycaemia as a result of their underlying metabolic variability. Such patients would also have less time in intermediate bands. The equivalent case states that survivors are less variable and thus easier to control, resulting in the more normal, consistent glycaemia associated with improved outcomes. This overall case suggests glycaemia and outcomes are driven by patient condition, regardless of GC protocol, or even that ineffective GC causes harm [5].

Separating these two interpretations would clarify the debate, research and practice in GC. In the first case, do we need better control, including any new sensors and devices, to achieve safe, effective and consistent GC for all patients in any unit? Or, in the second case, are GC and its outcomes merely a reflection of the underlying patient state and thus perhaps less necessary to control beyond a modest lowering? In summary, are patient glycaemia and outcome (predominantly) a function of the GC achieved, or are they driven by patient condition?

Aim and research question

The aim of this study was to separate these two interpretations by asking the question, Are patients who die harder (metabolically) to control than patients who live? If they are harder to control, then it could be considered that patient condition drives glycaemia and outcome. If not, then the quality of control could have the greater influence.

This question is addressed through a retrospective analysis of clinical data and metabolic level and variability using a clinically validated metabolic model [46,47,48,49]. Lower metabolic level, captured as lower insulin sensitivity (SI), indicates that increased insulin is required to lower BG, which increases hypoglycaemic risk if there is variability. Greater metabolic variability, captured as greater hour-to-hour percentage change in insulin sensitivity (%ΔSI), translates to greater outcome glycaemic variability in response to insulin. Thus, both measures capture the level of difficulty in GC, where a constant level of SI could be readily titrated to an optimal insulin dose, but unpredictable patient variability can result in excessive hyper- and hypo- glycaemia and glycaemic variability.

In short, do non-survivors have lower SI and/or greater %ΔSI, indicative of being harder to control than survivors? A positive answer would indicate that the well-known associations between glycaemia and outcome are driven more predominantly by patient condition. If non-survivors were similarly difficult or easier to control than survivors, it would indicate that the quality of GC achieved predominates in determining glycaemia and outcome.

Methods

To answer the research question, metabolic state and variability were analysed using model-based SI. Key outcomes included the following:

-

Difference and/or equivalence of SI in survivors and non-survivors

-

Difference and/or equivalence of %ΔSI in survivors and non-survivors

These outcomes are compared in 6-h blocks across the first 72 h of patient GC in the ICU.

Patient cohort

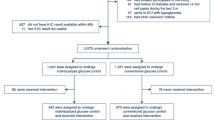

Retrospective clinical data from 371 patients on the Specialised Relative Insulin Nutrition Tables (SPRINT) GC protocol in the Christchurch Hospital Department of Intensive Care between August 2005 and April 2007 [10] were analysed. The SPRINT protocol modulated both insulin and nutrition, averaging approximately 16 BG measures per day. Figure 1 shows the inclusion criteria for study analysis. Of 371 patients, 231 patients were started on SPRINT within 12 h of ICU admission, and 145 underwent at least 24 h of insulin therapy. These patients make up Cohort 1, with demographic data listed in Table 1.

Cohort selection from original 371 patients who treated according to the Specialised Relative Insulin Nutrition Tables (SPRINT) protocol. The first comparison compares survivors and non-survivors from Cohort 1, using as much data as possible and excluding patients with a very short intensive care unit (ICU) stay. The second comparison uses Cohort 2 to assess the impact of competing risk due to patient dropout

Glycaemically, survivors and non-survivors had similar times in band. The cohort median BG was statistically different (5.8 vs 5.5 mmol/L, p < 0.01), but this difference is within clinical equivalence (explained in ‘Analyses and statistics’ subsection below) and thus considered not clinically significant. Maximum Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores on Day 1, excluding Glasgow Coma Scale score [50], were higher for non-survivors, as expected, and detailed breakdowns for specific co-morbidities showed similar trends. All other demographics are similar, except for an expected difference in Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score.

To assess any impact of patient dropout, in Cohort 2, we considered only patients who underwent at least 72 h of GC (80 patients). In the first cohort, we assessed as much data as possible, excluding patients with very short ICU stays, whereas in the second cohort, we assessed the impact of competing risk in the analysis of SI and mortality outcome due to patient dropout. Demographic data of Cohort 2 are shown in Table 2 and are similar to those of Cohort 1.

Model-based SI

The physiological model-based glucose-insulin dynamics represented in Fig. 2 are defined by the following equations [49]:

Schematic representation of the glucose-insulin model showing the physiological compartments and clearances, as well as the appearance of exogenous insulin and carbohydrate, and their kinetic pathways. CNS Central nervous system, EGP Endogenous glucose production, PN Parenteral nutrition, SI Insulin sensitivity

The main model variables and parameters are described in Table 3, and the full model details and physiological relevance are presented in Additional file 1. SI is a patient-specific, time-varying parameter that characterises the systemic response to glucose and insulin administration. The SI units used (L/mU/minute) are consistent with a rate parameter for assessing the rate of insulin-mediated glucose removal, where litres per minute is a rate of flow or uptake and mU−1 makes it dependent on current insulin concentration. When SI is multiplied by the average hourly glucose for the period over which SI is calculated, the units become consistent with those used in the gold standard hyperinsulinaemic, euglycaemic clamp assessment of SI [51, 52]. Integral-based fitting [53] is used to determine SI hourly from clinical BG, insulin and nutrition-related data.

SI level is determined hourly for each patient, and the forward SI variability (%ΔSI) is defined as the hour-to-hour percentage change in SI, calculated as follows:

A previous retrospective analysis showed that the SI of critically ill patients was lower and more variable during the first 24 h of the ICU stay, where SI was analysed in 6-h blocks [35, 54]. However, differences between survivors and non-survivors or other clinical outcomes were not analysed.

Analyses and statistics

In this study, we analysed SI over the first 3 days (72 h) of GC and compared the evolution of SI and %ΔSI for survivors and non-survivors. Only patients who received insulin therapy under the SPRINT protocol during the first 12 h of ICU admission are included, so there are only small differences between ICU admission and time on the SPRINT protocol. This choice avoids any bias due to different time since ICU admission, given the evolution seen in previous studies [35, 36, 54] for the cohort as a whole.

SI and %ΔSI were analysed in 6-h blocks. Cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) for each metric were created for survivors and non-survivors over each 6-h block. These CDFs show the overall distribution and are defined exactly as the integral of the probability density function capturing the histogram of the data. Therefore, they clearly define the median and any percentile likelihood (y-axis) for any given SI or %ΔSI values (x-axis).

Hypothesis testing was used to examine differences, with p ≤ 0.05 used as a threshold for statistical significance. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to identify bias and shape difference in distributions of %ΔSI. Although it is not certain if each family of comparisons is strictly independent (i.e., each 6-h block may depend on surrounding blocks), for completeness and to be conservative, a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to generalise the results. In both Cohorts 1 and 2, there were 12 comparisons made, bringing the significance level to p = 0.004 (0.05/12) [55].

Owing to a relatively large number of data points, bootstrapping was used to examine the difference between median SI and median %ΔSI between survivor and non-survivor cohorts [55]. Data were bootstrapped 1000 times with replacement to generate cohorts of the same size as the original data for a given 6-h block. A 95% CI for the difference between median SI values and between median %ΔSI values was generated. Where this CI does not cross zero, differences in medians are statistically significant with p ≤ 0.05 [55]. A 99.6% CI, consistent with using p = 0.004, was taken into account when considering Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Hypothesis testing was used to examine differences between cohorts and to assemble evidence to reject the null hypothesis of data being drawn from the same underlying distribution. However, it cannot provide evidence for equivalence, especially for large sample sizes [55,56,57]. Equivalence testing was used to assess the impact of these differences on clinical decision making, regardless of the underlying statistical significance (p value). Thus, it is important to note that a difference can be statistically significantly different and also equivalent, because the first is a statistical measure and the second is a measure of the clinical impact of the difference in the two distributions.

An analysis was done to determine an equivalence interval for changes in SI, as reflected by clinical significance. This interval thus defines the range within which a difference of medians cannot be distinguished, owing to either measurement error and/or clinical significance. Clinical significance was defined as the change in SI required to exceed BG measurement error (SD ±9.4% [58]) or to cause a change in model-based insulin dose recommendations. These calculations can be found in Additional file 2. In this case, the equivalence range due to measurement error was the narrowest across the range of clinical inputs observed. This choice provides the narrowest range and thus the most conservative or stringent test of equivalence.

The resulting equivalence range for %ΔSI is typically about 12–15%, but it is dependent on BG. Thus, any changes in SI or %ΔSI within these ranges cannot be detected as different from a change due to measurement error and are thus equivalent. Equivalence testing is independent of p values and hypothesis testing.

Equivalence was tested for SI and %ΔSI over each 6-h interval. For SI, the bootstrapped percentage difference in median SI was compared with the equivalence range. If the 95% CI for the bootstrapped percentage difference in SI medians was within the equivalence range, then equivalence in SI was accepted (⇔). For %ΔSI, the absolute difference in median %ΔSI was examined. If the 95% CI for the bootstrapped difference in median %ΔSI was within the equivalence range, then equivalence in %ΔSI was accepted (⇔). Conversely, in both cases, if the 95% CI was outside the equivalence range, equivalence was thus rejected (×). Finally, equivalence was tested for BG in Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 as a whole, using the reported equivalence range of ±9.4%, which is 1 SD of the relevant BG measurement error [58]. Equivalence testing in this last case determined whether the significant differences in median cohort BG in Tables 1 and 2 were clinically significant.

Results

SI level

Table 4 shows median SI and IQR for survivors and non-survivors in both Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 over the first 72 h. The CDFs for SI over each 6 h block for Cohort 1 are shown in Fig. 3. Overall, SI level increases over time, matching [35], where non-survivors have higher SI than survivors.

In Cohort 1, the difference between median SI levels was not statistically significant (95% CI crosses zero) for the first 48 h, except for 6–11 h and 30–35 h. By Day 3, the differences became significant, except for the 66–71 h block. With the Bonferroni correction applied, only the 6–11 h and 48–53 h blocks remained statistically different. In every 6-h block, non-survivors had higher SI levels than survivors. Figure 4 shows results of the equivalence test for each 6-h block. At no time did the median and 95% CI values for the percentage difference of SI medians in survivors and non-survivors fall within the equivalence range. Therefore, the median SI level was never equivalent in survivors and non-survivors, regardless of p values assessing difference.

Equivalence testing on insulin sensitivity (SI) for each 6 h block for Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. The solid blue lines give equivalence ranges for 9.4% blood glucose error [58] and the blue dotted lines a smaller 7% error reported for the device used in highly controlled tests [105]. Equivalence is accepted if the 95% CI (bars) of bootstrapped percentage differences in median SI values is within the equivalence range, and rejected otherwise (×)

The results were similar for Cohort 2. However, after Bonferroni correction, median SI was statistically different only for hours 48–53. Survivors and non-survivors were never equivalent, and SI was always higher for non-survivors in Cohort 2, all of whom had an ICU length of stay of 3 days or longer.

Figure 5 shows the evolution of median [IQR] SI and BG values over time between survivors and non-survivors for Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. In both cohorts, SI was higher for non-survivors, as reflected in Table 4, and this difference was greater as control progressed. In terms of BG, survivors and non-survivors had similar levels for most hours. Equivalence testing on overall BG distributions between survivors and non-survivors showed the median and 95% CI of the percentage change in median BG were 5.3 [2.6, 7.1] for Cohort 1 and 3.5 [0.9, 5.3] for Cohort 2, which were well within equivalence ranges of 7.0–9.4%. Thus, whereas the differences are statistically different, they confirm that the differences in the median BG values in Tables 1 and 2 are not clinically significant. It is important to note that these two figures do not necessarily reflect SI hour-to-hour variability at a per-patient level. Two patients could have equal variability in a 6-h period but at different hours, and thus appear different in SI level, which explains the need for a separate %ΔSI analysis assessing the hour-to-hour variability.

SI variability (%ΔSI)

Results for %ΔSI are shown in Table 5 and Fig. 6. Overall, SI variability decreased over time (IQR narrows) for both survivors and non-survivors, matching previously reported results [35]. In both Cohort 1 and Cohort 2, %ΔSI was not significantly different (p ≥ 0.11 in 11 of 12 blocks), especially when the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was made (p < 0.004 correction threshold). The 95% CI on median difference in %ΔSI (bias only) can be considered significant only for the 36–41 h and 42–47 h blocks in Cohort 1 and only for the 18–23 and 24–29 h blocks in Cohort 2 (bootstrapping, right-most column of Table 5), but these significances did not hold when the Bonferroni correction was made (99.6% CI). In all cases, these differences were not clinically significant. As shown in Fig. 7, the median and 95% CI change in %ΔSI difference was always within the equivalence range for both Cohorts 1 and 2. Therefore, SI variability assessed as %ΔSI in survivors and non-survivors was equivalent in every 6-h block to 72 h.

Cohort 1 cumulative hour-to-hour percentage changes in insulin sensitivity (%ΔSI) over 6-h time intervals for the first 72 h of glycaemic control. At any level of %ΔSI, the y-axis gives the percentage of %ΔSI values (decimal percentile) below this level. p Values were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

Equivalence testing on insulin sensitivity variability (hour-to-hour percentage change in insulin sensitivity [%ΔSI]) for each 6-h block for Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. The solid lines give equivalence ranges for 9.4% blood glucose error [58], and the dotted lines give a smaller 7% error reported for the device used in highly controlled tests [104]. Equivalence is accepted (⇔ in Table 5 ) if the 95% CI (bars) of bootstrapped difference in median %ΔSI are within the equivalence range, and rejected otherwise (×)

Key results

In summary, the key results are as follows:

-

SI level is not equivalent in any 6-h block within the first 72 h of GC, and it is sometimes statistically different between survivors and non-survivors.

-

SI level is higher in non-survivors than in survivors in every 6-h block for the first 72 h, and this difference becomes statistically significant as GC progresses.

-

SI variability is equivalent between survivors and non-survivors in any 6-h block within the first 72 h of GC.

-

Patient dropout had no impact on results, because Cohort 2 had the same key outcomes.

-

The major results are consistent, regardless of whether the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons is applied.

Thus, whereas survivors and non-survivors differed in their absolute SI, with non-survivors having higher SI, they were equivalent in their %ΔSI.

Discussion

Primary question

Patient-specific SI and SI variability metrics are used to assess underlying controllability between survivors and non-survivors. Both statistical difference and equivalence were tested in comparing these cohorts. Statistical difference (p < 0.05) tests whether the data come from similar or different distributions, whereas, in contrast, equivalence tests whether these values are clinically or physiologically equivalent, regardless of p value.

SI was statistically different between survivors and non-survivors for five of twelve 6-h periods. However, the cohorts were never clinically equivalent in SI for any period. Non-survivors had higher SI in every period, suggesting that slightly lower insulin doses would be required to achieve normo-glycaemia, which is also seen in the clinical results in Table 1. Key results were the same for both cohorts examined.

%ΔSI was equivalent between survivors and non-survivors for every period, and it was statistically different in only two periods. Equivalent variability under the same GC protocol would be reflected in similar times in glycaemic bands and in glycaemic levels for both survivors and non-survivors, as seen in Table 1. The results were the same for both cohorts. Median BG was higher in survivors (5.5 vs 5.8 mmol/L, p < 0.01 for both cohorts), but this difference was shown to be clinically equivalent in terms of measurement error and, in addition, would not change the clinical interventions.

Whereas SI level tends to determine the total insulin dose titrated, it is variability that determines the risks of insulin therapy and overall controllability. Overall, similar to higher SI for non-survivors and equivalent variability suggest that survivors and non-survivors are equally controllable, given an effective GC protocol. This outcome in turn suggests that the association between glycaemia and outcome is thus predominated by the quality of GC achieved and not by underlying patient variability. This result is important and has implications for GC study design and practice.

Validity of SI metric

The results rely on the validity of the model-based estimate of SI. The reliability of the SI metric is determined by the underlying data and the ability of the model to capture key glucose-insulin dynamics. The Intensive Control Insulin-Nutrition-Glucose (ICING) model used in the present study is structurally very similar to the Dynamic Insulin Sensitivity and Secretion Test model, for which the SI metric has correlated well with the gold standard euglycaemic clamp SI values [59,60,61,62], as have other very similar models using the SI metrics and pharmacodynamics used here [52]. The ICING model and its SI metric have been used successfully and safely to guide insulin therapy across different adult [47, 48, 63, 64] and neonatal [65, 66] intensive care settings and delivery methods. These clinical results suggest that the model is able of capturing and accounting for all major glucose-insulin dynamics, making the SI parameter, and its guiding of care via forward prediction, clinically useful.

In addition, treatment independence of the SI parameter has been assessed using clinical data from independent, matched patient cohorts [46, 67]. In the first case, two cohorts and protocols (Glucontrol [14] and SPRINT [10]) from Liège, Belgium, and Christchurch, New Zealand, were simulated with both protocols, and their glycaemic level and variability were compared with those obtained clinically. Consistency in simulation results across cohorts and high similarity in stochastic plots of SI variability further validated the treatment and cohort independence of SI [68]. In the second case, this similarity and cross-validation were repeated across three medical ICU cohorts, further validating these outcomes [67]. Recent work suggests that it is an underlying similarity in SI variability, independent of absolute SI level, that drives GC outcomes [46, 67, 68]. This similarity thus also drove the observed consistency between clinical results using this model and SI metric for GC in two very different ICUs [64].

Moreover, SI has been shown to assess and reflect clinically expected changes in SI and metabolism for important intensive care interventions. The impact of glucocorticoids [69] and β-blockers [70] on SI level and %ΔSI was shown to be limited in the context of the SPRINT protocol. More specifically, insulin and nutrition inputs were not statistically different in this study between survivors and non-survivors (p > 0.34) (Table 1), where increasing insulin use would reflect increased insulin resistance (lower SI). These results thus suggest that glucocorticoid-mediated influence on SI does not have any net impact on the two groups, as there was such a difference in the study by Pretty et al. [69]. Additionally, the impact of exogenous nutrition and incretin effects seen in changes in SI [71], the impact on SI from haemodialysis altering insulin clearance [72], and finally the insulin resistance observed on and off therapeutic hypothermia [73] were all assessed using hourly identified SI based on the same model. Each of these studies demonstrated the ability of SI and its changes to reflect clinically expected outcomes and correlated with expectations for the given intervention.

Other factors, such as insulin administration form (bolus vs continuous dosing), have little impact on the hourly calculated SI value. In this study, both survivors and non-survivors were treated with bolus doses, eliminating any effect that could exist for this comparison. Glucose sensor errors could have a more measurable impact on SI calculation [74], but the same glucometers were used for all patients, similarly ameliorating this affect. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) delivers observations indicating greater apparent spontaneous variability in BG levels than seen with typical intermittent sampling. However, it is important to note that a major part of this CGM-observed BG variability is due not to patient metabolism but directly to sensor drift, changes in the in situ environment of the sensor, patient position and other factors [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Thus, what is captured by CGM may be either realistic or an artefact or some combination. However, differentiating these systemic errors from real BG variability is not currently possible without another reference measurement at the same rate. As a result, the hourly determined SI values used here are appropriate, particularly with regard to the measurement rate in the data, which cannot capture any real glycaemic variability in the data that occurs and resolves between measurements. Hence, the overall approach used here is appropriate to the data and its sampling rate and does captures very high levels of variability, as seen in Fig. 6 with changes in SI up to 640%. Two examples of SI profiles over time, indicating the actual variability possible, are shown in Additional file 1.

Glucose complexity has been associated with mortality [83, 84] but cannot be measured at the bedside in real time as glycaemic levels, time in band, or variability can. Equally, there is not the strong physiological evidence that would support this association which exists for the other metrics considered, and there are questions about its proper use in analysing continuous glucose data to create these associations [85, 86].

The presented results suggest non-survivors have higher SI, which at first appeared counter-intuitive. However, it can be hypothesised that some non-survivors may have had weaker inflammatory immune responses and/or weaker inflammatory counter-regulatory response to insult. Although the literature commonly points to increased inflammatory markers in non-survivors (e.g., [87, 88]), there is evidence of instances where compromised immune response leads to increased mortality (e.g., [89,90,91,92]). These physiological responses (both inflammatory [93,94,95,96,97,98] and counter-regulatory [94, 99,100,101,102]) drive hyperglycaemia via the inflammatory marker-induced actions that reduced the effective SI values analysed here. They are also two of three major drivers of hyperglycaemia, the third being high glucose itself. Hence, weakened responses in those who die would lead to slightly higher SI and thus may be the cause of the slightly higher SI and slightly lower, clinically speaking, insulin use in this cohort. We do not have evidence to prove this hypothesis, but it would make a good hypothesis for a future study.

In particular, SI is approximately 20% higher, on average, for non-survivors, ranging from about 9–40% over time periods, which is at or within the level of change in SI required to induce, in SPRINT, a 1-U/h change in insulin dose, considering a median of 3 U/h (see Additional file 2: Figure S2.5). Thus, this difference changed few interventions, as seen in Table 1 (median [IQR] of 3 [2, 3] U/h for both survivors and non-survivors), where feed is also similar. Excluding dropout in Cohort 2, the differences remained but were much smaller (approximately 12%). Thus, although SI is higher for non-survivors and not equivalent to SI of survivors, on the basis of the most conservative estimate (percentage change in SI to reach 9.4% BG measurement error), this difference in SI did not have a significant clinical impact in terms of interventions, where an approximately 20–25% change in SI was required to change an intervention (see Additional file 2: Figure S2.5).

One advantage of the model-based SI used here is that it accounts for all insulin and nutrition inputs as well as resulting changes in glycaemia, allowing the SI metric to reflect the underlying ability of the body to use insulin for glucose uptake. Using SI thus allows an objective numerical analysis to be carried out and for results to be generalised to other mixed ICU populations.

Advantages and limitations

A first potential limitation of this work is that, as with all models, the ICING model has ranges for BG and nutrition-insulin interventions in which it is most accurate [103]. These ranges span what is typically observed in the Christchurch Hospital ICU, including BG within the 4–10 mmol/L range and insulin and nutrition treatments within 0–10 U/h and 20–120% of goal feed, respectively. If this analysis were to be repeated in ICUs or with protocols where treatments may commonly be given outside these ranges, or where persistent hyper- and/or hypoglycaemia were common, there would be greater potential for analytical error. However, in this case, the clinical data and inputs all fall within the ideal range for the ICING model.

A significant advantage of this work is that it uses data of sufficient detail and quality for further analysis. Many studies do not record (or report) detailed nutrition and/or insulin inputs, so analyses are limited by either disregarding nutrition in the first place or considering daily averages and effects. This data set included all time-valued changes in insulin and nutrition in 1-2 h intervals, as well as all BG measures, thus allowing a much higher degree of resolution in the calculation of time-varying SI. The limitation is that this analysis would be difficult to repeat with data from other, larger studies because of this lack of detail and/or temporal resolution of the GC data collected.

This study is limited in its retrospective nature and because it was performed with data from a single centre. However, the data cover a relatively large, generalised patient cohort spanning several years of clinical practice. Illness and injury can affect the inflammatory response and thus the SI. The analysis cohorts were therefore selected on the basis of starting GC within the first 12 h of ICU stay to reduce the effect of time-varying degrees of illness and injury on the time-varying analysis of SI.

Conclusions

The results we report show equivalent metabolic variability between survivors and non-survivors and that non-survivors had higher SI. These results are based on a numerical, objective, model-based SI metric which takes into consideration both nutrition-insulin inputs and metabolic outcomes. The underlying data cohort is derived from a mixed medical ICU, and as previous work has shown consistency in variability across different cohorts, countries and centres, it is likely that the results of this study are not specific to the original data set. Overall, these results suggest that glycaemic outcomes and differences between survivors and non-survivors are thus more a function of the control provided rather than the underlying metabolic condition.

This outcome has implications for future study and protocol design in this area. Future work is required to confirm these results and explore the relationship between outcomes and GC.

Abbreviations

- %ΔSI:

-

Hour-to-hour percentage change in insulin sensitivity

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- BG:

-

Blood glucose

- CDF:

-

Cumulative distribution function

- CGM:

-

Continuous glucose monitoring

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- EGP:

-

Endogenous glucose production

- GC:

-

Glycaemic control

- ICING:

-

Intensive Control Insulin-Nutrition-Glucose model

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PN:

-

Parenteral nutrition

- SI:

-

Insulin sensitivity

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SPRINT:

-

Specialised Relative Insulin Nutrition Tables protocol

References

Marik PE. Precision glycemic control in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1433–4.

Schultz MJ, Harmsen RE, Spronk PE. Clinical review: strict or loose glycemic control in critically ill patients - implementing best available evidence from randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2010;14:223.

Gunst J, Van den Berghe G. Blood glucose control in the ICU: don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater! Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1478–81.

Preiser JC, Straaten HM. Glycemic control: please agree to disagree. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1482–4.

Marik PE. Tight glycemic control in acutely ill patients: low evidence of benefit, high evidence of harm! Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1475–7.

Polderman KH, Girbes AR. Intensive insulin therapy: of harm and health, of hypes and hypoglycemia. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:246–8.

Brunkhorst FM, Reinhart K. Intensive insulin therapy in the ICU: benefit versus harm? Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1302.

Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–67.

Krinsley JS. Effect of an intensive glucose management protocol on the mortality of critically ill adult patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:992–1000.

Chase JG, Shaw G, Le Compte A, Lonergan T, Willacy M, Wong XW, et al. Implementation and evaluation of the SPRINT protocol for tight glycaemic control in critically ill patients: a clinical practice change. Crit Care. 2008;12:R49.

Reed CC, Stewart RM, Sherman M, Myers JG, Corneille MG, Larson N, et al. Intensive insulin protocol improves glucose control and is associated with a reduction in intensive care unit mortality. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1048–55.

Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:449–61.

Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–97.

Preiser JC, Devos P, Ruiz-Santana S, Melot C, Annane D, Groeneveld J, et al. A prospective randomised multi-centre controlled trial on tight glucose control by intensive insulin therapy in adult intensive care units: the Glucontrol study. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1738–48.

Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:125–39.

Marik PE, Preiser JC. Toward understanding tight glycemic control in the ICU: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;137:544–51.

Fahy BG, Sheehy AM, Coursin DB. Glucose control in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1769–76.

Treggiari MM, Karir V, Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Daniel S, Deem SA. Intensive insulin therapy and mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2008;12:R29.

Arabi YM, Dabbagh OC, Tamim HM, Al-Shimemeri AA, Memish ZA, Haddad SH, et al. Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy: a randomized controlled trial in medical and surgical critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3190–7.

De La Rosa C, Donado JH, Restrepo AH, Quintero AM, Gonzalez LG, Saldarriaga NE, et al. Strict glycaemic control in patients hospitalised in a mixed medical and surgical intensive care unit: a randomised clinical trial. Crit Care. 2008;12:R120.

Griesdale DE, de Souza RJ, van Dam RM, Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Malhotra A, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-SUGAR study data. CMAJ. 2009;180:821–7.

Wiener RS, Wiener DC, Larson RJ. Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:933–44.

Preiser JC, Devos P, Chiolero R. Which factors influence glycemic control in the intensive care unit? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:205–10.

Ali NA, O’Brien Jr JM, Dungan K, Phillips G, Marsh CB, Lemeshow S, et al. Glucose variability and mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2316–21.

Egi M, Bellomo R, Stachowski E, French CJ, Hart G. Variability of blood glucose concentration and short-term mortality in critically ill patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:244–52.

Egi M, Finfer S, Bellomo R. Glycemic control in the ICU. Chest. 2011;140:212–20.

Krinsley JS. Glycemic variability: a strong independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3008–13.

Waeschle RM, Moerer O, Hilgers R, Herrmann P, Neumann P, Quintel M. The impact of the severity of sepsis on the risk of hypoglycaemia and glycaemic variability. Crit Care. 2008;12:R129.

Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Jacka MJ, Egi M, Hart GK, George C, ANZICS CORE Management Committee. The impact of early hypoglycemia and blood glucose variability on outcome in critical illness. Crit Care. 2009;13:R91.

Donati A, Damiani E, Domizi R, Botticelli L, Castagnani R, Gabbanelli V, et al. Glycaemic variability, infections and mortality in a medical-surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Resusc. 2014;16:13–23.

Kauffmann RM, Hayes RM, Buske BD, Norris PR, Campion Jr TR, Dortch M, et al. Increasing blood glucose variability heralds hypoglycemia in the critically ill. J Surg Res. 2011;170:257–64.

Krinsley JS, Schultz MJ, Spronk PE, Harmsen RE, van Braam HF, van der Sluijs JP, et al. Mild hypoglycemia is independently associated with increased mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care. 2011;15:R173.

NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1108–18.

Egi M, Bellomo R, Stachowski E, French CJ, Hart GK, Taori G, et al. Hypoglycemia and outcome in critically ill patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:217–24.

Pretty CG, Le Compte AJ, Chase JG, Shaw GM, Preiser JC, Penning S, et al. Variability of insulin sensitivity during the first 4 days of critical illness: implications for tight glycemic control. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2:17.

Langouche L, Vander Perre S, Wouters PJ, D’Hoore A, Hansen TK, Van den Berghe G. Effect of intensive insulin therapy on insulin sensitivity in the critically ill. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3890–7.

Pielmeier U, Rousing ML, Andreassen S, Nielsen BS, Haure P. Decision support for optimized blood glucose control and nutrition in a neurotrauma intensive care unit: preliminary results of clinical advice and prediction accuracy of the Glucosafe system. J Clin Monit Comput. 2012;26:319–28.

Krinsley JS, Bruns DE, Boyd JC. The impact of measurement frequency on the domains of glycemic control in the critically ill - a Monte Carlo simulation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:237–45.

Chase JG, Le Compte AJ, Suhaimi F, Shaw GM, Lynn A, Lin J, et al. Tight glycemic control in critical care – the leading role of insulin sensitivity and patient variability: a review and model-based analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;102:156–71.

Al-Tarifi A, Abou-Shala N, Tamim HM, Rishu AH, Arabi YM. What is the optimal blood glucose target in critically ill patients? A nested cohort study. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:207–11.

Omar AS, Salama A, Allam M, Elgohary Y, Mohammed S, Tuli AK, et al. Association of time in blood glucose range with outcomes following cardiac surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:14.

Krinsley JS, Preiser JC. Time in blood glucose range 70 to 140 mg/dl >80% is strongly associated with increased survival in non-diabetic critically ill adults. Crit Care. 2015;19:179.

Signal M, Le Compte A, Shaw GM, Chase JG. Glycemic levels in critically ill patients: are normoglycemia and low variability associated with improved outcomes? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:1030–7.

Penning S, Chase JG, Preiser JC, Pretty CG, Signal M, Melot C, et al. Does the achievement of an intermediate glycemic target reduce organ failure and mortality? A post hoc analysis of the Glucontrol trial. J Crit Care. 2014;29:374–9.

Penning S, Pretty C, Preiser JC, Shaw GM, Desaive T, Chase JG. Glucose control positively influences patient outcome: a retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2015;30:455–9.

Chase JG, Suhaimi F, Penning S, Preiser JC, Le Compte AJ, Lin J, et al. Validation of a model-based virtual trials method for tight glycemic control in intensive care. Biomed Eng Online. 2010;9:84.

Evans A, Shaw GM, Le Compte A, Tan CS, Ward L, Steel J, et al. Pilot proof of concept clinical trials of Stochastic Targeted (STAR) glycemic control. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:38.

Fisk L, Lecompte A, Penning S, Desaive T, Shaw G, Chase G. STAR development and protocol comparison. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;59:3357–64.

Lin J, Razak NN, Pretty CG, Le Compte A, Docherty P, Parente JD, et al. A physiological Intensive Control Insulin-Nutrition-Glucose (ICING) model validated in critically ill patients. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;102:192–205.

Chase JG, Pretty CG, Pfeifer L, Shaw GM, Preiser JC, Le Compte AJ, et al. Organ failure and tight glycemic control in the SPRINT study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R154.

Lotz TF, Chase JG, McAuley KA, Lee DS, Lin J, Hann CE, et al. Transient and steady-state euglycemic clamp validation of a model for glycemic control and insulin sensitivity testing. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8:338–46.

Lotz TF, Chase JG, McAuley KA, Shaw GM, Wong XW, Lin J, et al. Monte Carlo analysis of a new model-based method for insulin sensitivity testing. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2008;89:215–25.

Hann CE, Chase JG, Lin J, Lotz T, Doran CV, Shaw GM. Integral-based parameter identification for long-term dynamic verification of a glucose-insulin system model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;77:259–70.

Thomas F, Pretty CG, Fisk L, Shaw GM, Chase JG, Desaive T. Reducing the impact of insulin sensitivity variability on glycaemic outcomes using separate stochastic models within the STAR glycaemic protocol. Biomed Eng Online. 2014;13:43.

Motulsky H. Intuitive biostatistics: a nonmathematical guide to statistical thinking. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Motulsky H. Common misconceptions about data analysis and statistics. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:2126–32.

Goodman SN. Toward evidence-based medical statistics. 1: The P value fallacy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:995–1004.

Freckmann G, Baumstark A, Jendrike N, Zschornack E, Kocher S, Tshiananga J, Heister F, et al. System accuracy evaluation of 27 blood glucose monitoring systems according to DIN EN ISO 15197. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:221–31.

McAuley KA, Berkeley JE, Docherty PD, Lotz TF, Te Morenga LA, Shaw GM, et al. The dynamic insulin sensitivity and secretion test—a novel measure of insulin sensitivity. Metabolism. 2011;60:1748–56.

Lotz TF, Chase JG, McAuley KA, Shaw GM, Docherty PD, Berkeley JE, et al. Design and clinical pilot testing of the model-based Dynamic Insulin Sensitivity and Secretion Test (DISST). J Diab Sci Technol. 2010;4:1408–23.

Docherty PD, Chase JG, Lotz T, Hann CE, Shaw GM, Berkeley JE, et al. DISTq: an iterative analysis of glucose data for low-cost, real-time and accurate estimation of insulin sensitivity. Open Med Inform J. 2009;3:65–76.

Docherty PD, Chase JG, Lotz TF, Hann CE, Shaw GM, Berkeley JE, et al. Independent cohort cross-validation of the real-time DISTq estimation of insulin sensitivity. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;102:94–104.

Evans A, Le Compte A, Tan CS, Ward L, Steel J, Pretty CG, et al. Stochastic targeted (STAR) glycemic control: design, safety, and performance. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:102–15.

Stewart KW, Pretty CG, Tomlinson H, Thomas FL, Homlok J, Noemi SN, et al. Safety, efficacy and clinical generalization of the STAR protocol: a retrospective analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:24.

Dickson JL, LeCompte AJ, Floyd RP, Chase JG, Lynn A, Shaw GM. Development and optimisation of stochastic targeted (STAR) glycaemic control for pre-term infants in neonatal intensive care. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2013;8:215–21.

Le Compte A, Chase JG, Lynn A, Hann C, Shaw G, Wong XW, et al. Blood glucose controller for neonatal intensive care: virtual trials development and first clinical trials. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:1066–81.

Dickson JL, Stewart KW, Pretty CG, Flechet M, Desaive T, Penning S, et al. Generalisability of a virtual trials method for glycaemic control in intensive care. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. doi:10.1109/TBME.2017.2686432.

Suhaimi F, Le Compte A, Preiser JC, Shaw GM, Massion P, Radermecker R, et al. What makes tight glycemic control tight? The impact of variability and nutrition in two clinical studies. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4:284–98.

Pretty C, Chase JG, Lin J, Shaw GM, Le Compte A, Razak N, et al. Impact of glucocorticoids on insulin resistance in the critically ill. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;102:172–80.

Pretty CG. Analysis, classification and management of insulin sensitivity variability in a glucose-insulin system model for critical illness. Christchurch: Dissertation, University of Canterbury, Department of Mechanical Engineering; 2012.

Jamaludin UK, Docherty PD, Chase JG, Le Compte A, Shaw GM, Desaive T, et al. Observation of incretin effects during enteral feed transitions of critically ill patients. ESPEN J. 2012;7:e154–9.

Jamaludin UK, Docherty PD, Chase JG, Shaw GM. Impact of haemodialysis on insulin kinetics of acute kidney injury patients in critical care. J Med Biol Eng. 2015;35:125–33.

Sah Pri A, Chase JG, Pretty CG, Shaw GM, Preiser JC, Vincent JL, et al. Evolution of insulin sensitivity and its variability in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients treated with hypothermia. Crit Care. 2014;18:586.

Pretty CG, Signal M, Fisk L, Penning S, Le Compte A, Shaw GM, et al. Impact of sensor and measurement timing errors on model-based insulin sensitivity. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2014;114:e79–86.

Signal M, Fisk L, Shaw GM, Chase JG. Concurrent continuous glucose monitoring in critically ill patients: interim results and observations. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1652–3.

Signal M, Pretty CG, Chase JG, Le Compte A, Shaw GM. Continuous glucose monitors and the burden of tight glycemic control in critical care: can they cure the time cost? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4:625–35.

Facchinetti A, Del Favero S, Sparacino G, Castle JR, Ward WK, Cobelli C. Modeling the glucose sensor error. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2014;61:620–9.

Reifman J, Rajaraman S, Gribok A, Ward WK. Predictive monitoring for improved management of glucose levels. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1:478–86.

Zimmermann JB, Lehmann M, Hofer S, Husing J, Alles C, Werner J, et al. Design of a prospective clinical study on the agreement between the Continuous GlucoseMonitor, a novel device for CONTinuous ASSessment of blood GLUcose levels, and the RAPIDLab® 1265 blood gas analyser: the CONTASSGLU study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012;12:24.

Breton M, Kovatchev B. Analysis, modeling, and simulation of the accuracy of continuous glucose sensors. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:853–62.

Kuure-Kinsey M, Palerm CC, Bequette BW. A dual-rate Kalman filter for continuous glucose monitoring. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;1:63–6.

Lunn DJ, Wei C, Hovorka R. Fitting dynamic models with forcing functions: application to continuous glucose monitoring in insulin therapy. Stat Med. 2011;30:2234–50.

Brunner R, Adelsmayr G, Herkner H, Madl C, Holzinger U. Glycemic variability and glucose complexity in critically ill patients: a retrospective analysis of continuous glucose monitoring data. Crit Care. 2012;16:R175.

Lundelin K, Vigil L, Bua S, Gomez-Mestre I, Honrubia T, Varela M. Differences in complexity of glycemic profile in survivors and nonsurvivors in an intensive care unit: a pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:849–54.

Thomas F, Signal M, Chase JG. Using continuous glucose monitoring data and detrended fluctuation analysis to determine patient condition: a review. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:1327–35.

Signal M, Thomas F, Shaw GM, Chase JG. Complexity of continuous glucose monitoring data in critically ill patients: continuous glucose monitoring devices, sensor locations, and detrended fluctuation analysis methods. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1492–506.

Kinasewitz GT, Yan SB, Basson B, Comp P, Russell JA, Cariou A, et al. Universal changes in biomarkers of coagulation and inflammation occur in patients with severe sepsis, regardless of causative micro-organism [ISRCTN74215569]. Crit Care. 2004;8:R82–90.

Pachaly MA, do Nascimento MM, Suliman ME, Hayashi SY, Riella MC, Manfro RC, et al. Interleukin-6 is a better predictor of mortality as compared to C-reactive protein, homocysteine, pentosidine and advanced oxidation protein products in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2008;26:204–10.

Hall MW, Geyer SM, Guo CY, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Jouvet P, Ferdinands J, et al. Innate immune function and mortality in critically ill children with influenza: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:224–36.

Stanojcic M, Chen P, Xiu F, Jeschke MG. Impaired immune response in elderly burn patients: new insights into the immune-senescence phenotype. Ann Surg. 2016;264:195–202.

Cabrera-Cancio MR. Infections and the compromised immune status in the chronically critically ill patient: prevention strategies. Respir Care. 2012;57:979–92.

Kumar M, Roe K, Nerurkar PV, Namekar M, Orillo B, Verma S, et al. Impaired virus clearance, compromised immune response and increased mortality in type 2 diabetic mice infected with West Nile virus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44682.

Weekers F, Giulietti AP, Michalaki M, Coopmans W, Van Herck E, Mathieu C, et al. Metabolic, endocrine, and immune effects of stress hyperglycemia in a rabbit model of prolonged critical illness. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5329–38.

Langouche L, Vanhorebeek I, Van den Berghe G. The role of insulin therapy in critically ill patients. Treat Endocrinol. 2005;4:353–60.

Butler SO, Btaiche IF, Alaniz C. Relationship between hyperglycemia and infection in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:963–76.

Fernandez-Real JM, Broch M, Richart C, Vendrell J, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ricart W. CD14 monocyte receptor, involved in the inflammatory cascade, and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1780–4.

Spindler MP, Ho AM, Tridgell D, McCulloch-Olson M, Gersuk V, Ni C, et al. Acute hyperglycemia impairs IL-6 expression in humans. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2016;4:91–7.

Turina M, Fry DE, Polk Jr HC. Acute hyperglycemia and the innate immune system: clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1624–33.

Krogh-Madsen R, Moller K, Dela F, Kronborg G, Jauffred S, Pedersen BK. Effect of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia on the response of IL-6, TNF-α, and FFAs to low-dose endotoxemia in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E766–72.

McCowen KC, Malhotra A, Bistrian BR. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:107–24.

Dandona P, Mohanty P, Chaudhuri A, Garg R, Aljada A. Insulin infusion in acute illness. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2069–72.

Vanhorebeek I, Langouche L, Van den Berghe G. Glycemic and nonglycemic effects of insulin: how do they contribute to a better outcome of critical illness? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:304–11.

Chase JG, Andreassen S, Pielmeier U, Hann CE, McAuley KA, Mann JI. A glucose-insulin pharmacodynamic surface modeling validation and comparison of metabolic system models. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2009;4:355–63.

Chase JG, LeCompte A, Shaw GM, Blakemore A, Wong J, Lin J, et al. A benchmark data set for model-based glycemic control in critical care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2:584–94.

Scandinavian Evaluation of Laboratory Equipment for Primary Health Care (SKUP). Glucocard X-Meter: meter and test strips designed for glucose self-measurement manufactered by ARKRAY, Inc. Bergen: University of Bergen; 2006.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) and Royal Society of New Zealand Marie Curie International Research Staff Exchange Scheme (IRSES) programme; the MedTech Centre of Research Excellence (CoRE) and Tertiary Education Commission (TEC); and the New Zealand National Science Challenge 7, Science for Technological Innovation.

Availability of data and materials

The data reported are not publicly available. However, a subset is freely available elsewhere in an article published in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology [104], and the authors can make it available in de-identified form on request.

Authors’ contributions

VU carried out the main analysis and drafted the manuscript, with significant input from JLD, JGC and TD in results interpretation, methodological and statistical design, and manuscript formulation. GMS provided the initial clinical data, ongoing clinical interpretation of results, and input into the final manuscript. All authors had input into the redaction process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. Data is de-identified, and consent for its use and publication is approved by the Upper South Regional Ethics Committee.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

SPRINT was implemented as standard practice, and data audit and analysis were approved by the Upper South Regional Ethics Committee.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Metabolic system model and insulin sensitivity. This file presents additional details on the physiological model and methods used to calculate a patient’s time-varying insulin sensitivity used in this study. (DOCX 375 kb)

Additional file 2:

Clinical significance calculations. This file presents the underlying calculations used to define the clinical ‘equivalence range’ used in this study. (DOCX 68 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Uyttendaele, V., Dickson, J.L., Shaw, G.M. et al. Untangling glycaemia and mortality in critical care. Crit Care 21, 152 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1725-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1725-y