Abstract

Background and aim

The BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes are associated with an inherited susceptibility to breast cancer with a cumulative risk of 60% in BRCA 1 mutation carriers and of 30% in BRCA 2 mutation carriers. Several lifestyle factors could play a role in determining an individual’s risk of breast cancer. Obesity, changes in body size or unhealthy lifestyle habits such as smoking, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity have been evaluated as possible determinants of breast cancer risk. The aim of this study was to explore the current understanding of the role of harmful lifestyle and obesity or weight change in the development of breast cancer in female carriers of BRCA 1/2 mutations.

Methods

Articles were identified from MEDLINE in October 2020 utilizing related keywords; they were then read and notes, study participants, measures, data analysis and results were used to write this review.

Results

Studies with very large case series have been carried out but only few of them have shown consistent results. Additional research would be beneficial to better determine the actual role and impact of such factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common female malignancy worldwide. Approximately 5–10% of breast cancer cases are hereditary and arise from autosomal dominant mutations in specific cancer genes, including the two breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA 1 and BRCA 2. Women who carry these mutations have up to an 80% risk of developing breast cancer [1,2,3]. Identifying modifiable exposures is very important in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers. The onset of breast cancer in these women may be influenced by genetic factors such as AdipoQ gene polymorphism associated to alterations in adipokines [4,5,6]. Evidence suggests that additional modifying factors influence cancer penetrance in BRCA 1/2 mutations carriers. Exposure to environmental factors and unhealthy lifestyle factors, including obesity, change in body size, smoking, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity, have been suggested to increase breast cancer (BC) risk in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers [7,8,9]. An association of these factors has been widely reported to enhance the risk of developing cancer [10]. In a previous study of 2020 (Bruno et al.), we examined the relationships between selected lifestyle, metabolic exposures and BRCA related cancer in 502 women with BRCA mutations and found that increased fat mass and dysmetabolism were significantly associated with BC risk and had a greater effect in BRCA 2 positive women [11]. Obesity may increase BC risk through multiple mechanisms including insulin-resistance, metabolic syndrome, increased production of sex hormones and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). In 2020, Pasanisi et al. reported that a Mediterranean diet with protein restriction is effective in reducing potential modulators of BRCA penetrance [12].

Given the high penetrance of BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutations, prevention and lifestyle changes have an extremely important risk-reducing role in women who have a higher risk of developing breast cancer.

Methods

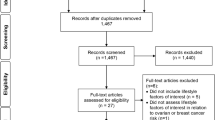

A broad review of the literature was carried out using MEDLINE (via PubMed) and sixteen articles published from 2002 to 2020, were selected from a total of one hundred. Search terms included keywords, combining the conditions (BRCA 1, BRCA 2, mutations, carriers, breast cancer risk), obesity, change in body weight and lifestyle (alcohol, smoking, physical inactivity). We included only original peer-reviewed articles on large prospective, retrospective and cohort studies that investigated obesity and unhealthy lifestyle habits as probable risk factors for the development of breast cancer. The selected articles concerned BRCA1 / 2 mutant women and investigated whether this status could increase the risk of breast cancer in relation to exposure to certain lifestyles. Studies that considered women without BRCA 1/2 mutations (in the case or control group), those with analyses that incorporated untested individuals or tested negative women, series with fewer than 100 patients enrolled, meta-analyses and reviews were excluded from this review (Fig. 1). One reviewer screened the titles and abstracts to select the studies and reviewed the full-text publications to confirm their eligibility and extract the relevant information from the included trials. A predefined spreadsheet (Excel 2007, Microsoft Corporation®) was used for data extraction. The most significant articles for lifestyles considered in this review are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Results

Inheritance of a BRCA 1 or 2 mutation is associated with an increased lifetime risk of breast cancer [13]. The relationship between anthropometric characteristics such as weight gain and /or BMI and breast cancer risk has been examined extensively [14]. In 2014, a meta analysis selected 44 articles, according to established quality criteria, considering smoking and alcohol consumption as a risk factor for the onset of BC. The authors found that subjects who smoked for more than 4 years were at greater BC risk than those who had never smoked (ES = 1.97; 95% CI = 1.43 to 2.72) while no correlation was highlighted in works that investigated the habitual intake of alcohol vs total abstemia (ES = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.50 to 1.23) [15].

Cancer penetrance associated to weight gain and changes in body composition

Weight gain and unfavorable changes in body composition with a significant increase in percentage body fat and decreased lean body mass are risk factors for breast cancer [16,17,18,19]. The relationship of anthropometric parameters and body weight changes with breast cancer risk has been examined extensively among women in the general population and several studies have investigated the impact of weight gain and cancer risk in women with a BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutation.

In a recent article of 2019, Qian F et al. investigated whether height or body mass index (BMI) could change the risk of developing breast cancer in 11,451 cases of breast cancer in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers. These authors found that height was positively associated with breast cancer risk (per 10 cm increase HR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.0 to 1.17; p = 1.17) while BMI was inversely associated with breast cancer risk (per 5 kg/ m2 increase HR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.90 to 0.98; p = 0.007) [20].

In 2005, a multicenter study by Kotsopoulos J et al. investigated body weight changes and breast cancer risk in a total of 3291 women who carried BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutations and provided information on weight at ages 18, 30 and 40 showing that a weight loss of at least 4.5 kg between ages 18 and 30 was associated with a significant reduction in breast cancer risk (34%) thereafter (OR = 0.66; 95% CI 0.46–0.93). Weight gain later in life was not associated with increased risk [21]. In a multicenter longitudinal cohort study of 2018, Kim SJ et al. investigated the relationship between body size and breast cancer risk in 3734 BRCA mutation carriers and found no association between height, BMI and weight change and breast cancer risk [22]. In a retrospective cohort study published in 2011, Manders P. et al. investigated the association between anthropomentric measures and BC risk in 719,0 women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation in pre and post menopause. The results reported in the work showed a decrease in risk in relation to BMI at 18 years while in postmenopausal age there was an increased risk respect to weight and in particular a higher BC risk in women weighing> 72 kg compared to those with weight < 72 kg, suggesting that postmenopausal mutated women should pay close attention to maintaining their body weight [23]. The summary list of these works is shown in Table 1

Cancer penetrance associated to harmful lifestyle habits

Smoking, drinking alcoholic beverages [24, 25] and physical inactivity [26] are well-known lifestyle risk factors for pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer in the general female population. The association between breast cancer risk and these unhealthy lifestyle choices has been also investigated in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers.

In a recent retrospective and prospective cohort study of 2020, Li H et al. investigated the association between smoking and alcohol consumption and the risk of developing breast cancer in 13,118 BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers and found that the only variable associated with the risk of BC for both carrier groups it was for mutated women who had smoked for at least 5 years before their first pregnancy compared to first-time mothers who had never smoked before. The results, found no correlation between BC cancer risk and alcohol intake in in both groups [27].

In 2020, Kehm RD et al. carried out a prospective cohort study on 15,550 women who had a familial breast cancer risk and investigated the association between recreational physical activity and decreased risk in adult women. The authors tested interactions of physical activity with predicted absolute familial BC risk based on BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation status and concluded that physical activity can reduce the risk of getting BC by about 20% even women with high penetrance due to their genetic family history or medical history [28].

van Erkelens A et al. in a cohort study in 2017, investigated the correlation of unhealthy lifestyles (alcohol intake, smoking and low physical activity) in 268,0 women with BRCa 1 and 2 mutation reporting that 38% of the participants had at least 2 high risk factors for BC, plus age the diagnosis of the mutation correlated with a decrease in physical activity (OR = 0.93/year, 95% CI = 0.86–0.99) and a prevalence of overweight (OR = 1.07/year, 95% CI =1.02–1.13) [29].

Dennis J et al. in 2010 conducted a case-control study of 1925 premenopausal women who carried a BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutation to investigate alcohol consumption and the risk of breast cancer, reporting an inversely proportional association between alcohol intake and increased risk of developing BC only in BRCA1-mutated women, while no association was found in BRCA2-mutated women (OR = 0.82; 95% CI 0.70–0.96) vs OR = 1.00; CI 0.71–1.41) [30].

In 2004, Ghadirian P et al. studied the correlation between smoking and the risk of breast cancer in a large cohort of BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers [31]. The authors, in a case-control study conducted on 1097 BRCA1 and 2 mutated women vs healthy women, found no significant association between the 2 groups considered (mutated vs healthy women) whether they were smokers or ex smokers or the age at which smoking began within 5 years of menarche (OR = 1.03;95% CI = 0.90 to 1.33) or before the first pregnancy concluding that smoking could not be a breast cancer risk in carriers of BRCA mutations.

Two other eligible studies by Ko KP et al. in 2018 and Ginsburg O et al. in 2009 investigated the association between smoking and increased breast cancer risk. The first was a cohort study of 7195 women that demonstrated an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer in women smokers with a BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutation (HR = 1.17; 95% CI 1.01–1.37), [32] and the second was a case control study of 2538 BRCA 1/2 carriers that showed a modest, but significant increase BC risk in BRCA 1 carriers with a past history of smoking (OR = 1.27; 95% CI 1.06–1.50) [33]. McGuire V et al. in 2006 investigated the association between alcohol consumption and increased risk of breast cancerin 323,0 women suggesting no positive association between alcohol intake and breast cancer risk in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers aged [34]. The summary list of these works is shown in Table 2

Cancer penetrance associated to oral contraceptive use

In the general population, multiparity and breastfeeding are among the protective factors of the risk of developing breast cancer, while the use of oral contraceptives could represent a predisposing factor; the data in the literature on the use of contraceptives in mutated women are still discordant but a possible role of estrogens on carcinogenesis has its foundation [35, 36]. The BRCA 1 /2 genes are involved in several functions including DNA damage and repair so the cancer-promoting effects of estrogen can be stronger in mutated BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 genes [37].

In 2018, Schrijver LH et al. investigated the association between the use of oral contraceptives and breast cancer risk in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers in a retrospective and prospective cohort study of 9839 cases. They found no association between the use of oral contraceptives and BC risk in women with a BRCA 1 mutation (HR: =1.08, 95% CI = 0.75 to 1.56) while for BRCA 2 mutation carriers, the authors highlighted an increased risk of developing breast cancer in mutated women taking oral contraceptives (HR: =1.75, 95% CI = 1.03 to 2.97) and this risk was also related to the duration of treatment particularly in the period prior to the first full-term pregnancy [38].

In a 2008 population-based study on 1469 women and 444 control subjects Lee E et al. investigated reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in BRCA 1/2 mutations carriers and non-carriers and reported no association between oral contraceptive use and BC risk in women carrying the mutations [39].

In 2002, in a matched case-control study on 1311 pairs of women with a known BRCA 1/2 mutation Narod SA et al. found an increased risk of breast cancer in women with a BRCA 1 mutation who first used oral contraceptives before age 30, or who used them for more than 5 years, while a similar risk did not appear in BRCA 2 mutation carriers [40]. The summary list of these works is shown in Table 3

Discussion

The presence of BRCA1 and 2 mutations may predispose to a higher risk of breast cancer in the percentage of 60 and 30% respectively. It is important to underline that not all mutated women will certainly develop cancer during their lifetime, but knowing the genetic or environmental risk factors that can increase the subjective predisposition to cancer is of fundamental importance. It has been proposed that several lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, poor nutrition or sedentariness may be potential modulators of BRCA penetrance, but the data reported in the literature are still conflicting and incomplete. The BRCA 1 gene and the BRCA 2 gene located on chromosome 17 and on chromosome 13, respectively (Fig. 2), are tumor suppressors capable of regulating cell proliferation and repairing any damage in DNA replication. It is therefore plausible that carcinogens that are contained, for example, in cigarette smoke or in some food may increase the risk of BC in female carriers of BRCA 1/2 mutations. The carcinogens present in the cigarette have the ability to infiltrate the pulmonary alveolus [41] and the bloodstream flowing into the breast by means of plasma lipoproteins [42, 43]. They are lipophilic, tobacco-related carcinogens can be stored in breast adipose tissue [33, 34] and then metabolized and activated by human mammary epithelial cells [44]. Many authors have reported that cigarette smoke contains various substances harmful to the breast parenchyma highlighting the presence of p53 mutation in the breast parenchyma of smokers compared to non-smokers [45]. On the others hand, heterocyclic amines and acrylamides, foods rich in starch and cooked at high temperatures (e.g., grilled or overcooked meat) or rich in animal protein or milk [11] may be potentially more likely to promote the development of breast cancer and favor BRCA penetrance. Although several studies have largely reported concordant results about the correlation between unhealthy lifestyle habits and sustained weight gain over time and breast cancer risk in the general population, few studies with large series have been conducted on women carrying the BRCA 1 and 2 mutation. This mini review considered 16 studies (12 prospective and 4 retrospective) that highlighted a discrepancy between the effects of some unhealthy lifestyle factors in increasing the risk of breast cancer. Alcohol consumption was not observed to have a key role in the onset of breast cancer while smoking, weight gain and physical inactivity, especially in postmenopausal age, seem to increase the risk of breast cancer.

Conclusion

Numerous factors have been reported to modify breast cancer risk. Our review of the specific literature has highlighted that there are few consistent results across different studies and that additional research would be beneficial to better determine the actual role and impact of such factors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable for that section.

References

King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2. Science. 2003;302(5645):643–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1088759.

Nkondjock A, Ghadirian P. Epidemiology of breast cancer among BRCA mutation carriers: an overview. Cancer Lett. 2004;205(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2003.10.005.

Pruthi S, Gostout BS, Lindor NM. Identification and Management of Women with BRCA mutations or hereditary predisposition for breast and ovarian Cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(12):1111–20. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0414.

Daniele A, Paradiso AV, Divella R, Digennaro M, Patruno M, Tommasi S, et al. The Role of Circulating Adiponectin and SNP276G>T at ADIPOQ Gene in BRCA-mutant Women. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2020;17(3):301–7. https://doi.org/10.21873/cgp.20190 PMID: 32345671; PMCID: PMC7259884.

Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14177 PMID: 25673413; PMCID: PMC4382211.

Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet. 2014;46(11):1173–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3097 Epub 2014 Oct 5. PMID: 25282103; PMCID: PMC4250049.

World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of Cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007.

Harvie M, Hooper L, Howell AH. Central obesity and breast cancer risk: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2003;4(3):157–73. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00108.x.

Pichard C, Plu-Bureau G, Neves ECM, Gompel A. Insulin resistance, obesity and breast cancer risk. Maturitas. 2008;60(1):19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.03.002.

Narod SA. Modifiers of risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(2):113–23. 12635174. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc726.

Bruno E, Oliverio A, Paradiso A, Daniele A, Tommasi S, Terribile DA, et al. Lifestyle Characteristics in Women Carriers of BRCA Mutations: Results From an Italian Trial Cohort. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;S1526–8209(20):30273–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2020.11.002 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33357965.

Pasanisi P, Bruno E, Venturelli E, Morelli D, Oliverio A, Baldassari I, et al. A Dietary Intervention to Lower Serum Levels of IGF-I in BRCA Mutation Carriers. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(9):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10090309 PMID: 30181513; PMCID: PMC6162406.

Bruno E, Oliverio A, Paradiso AV, Daniele A, Tommasi S, Tufaro A, et al. A Mediterranean Dietary Intervention in Female Carriers of BRCA Mutations: Results from an Italian Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3732. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123732 PMID: 33322597; PMCID: PMC7764681.

van den Brandt PA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson L, Folsom AR, et al. Pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies on height, weight, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(6):514–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/152.6.514 PMID: 10997541.

Friebel TM, Domchek SM, Rebbeck TR. Modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J National Cancer Institute. 2004;106(6):dju091. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju091.

Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R. Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obes Rev. 2011;12(4):282–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00805.x Epub 2010 Sep 29. PMID: 20880127.

Wang JS, Cai H, Wang CY, Zhang J, Zhang MX. Body weight changes in breast cancer patients following adjuvant chemotherapy and contributing factors. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2(1):105–10. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2013.209 Epub 2013 Oct 30. PMID: 24649316; PMCID: PMC3915700.

Shachar SS, Deal AM, Weinberg M, Williams GR, Nyrop KA, Popuri K, et al. Body Composition as a Predictor of Toxicity in Patients Receiving Anthracycline and Taxane-Based Chemotherapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(14):3537–43. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2266 Epub 2017 Jan 31. PMID: 28143874; PMCID: PMC5511549.

Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Longnecker MP, Baron J, Greenberg ER, et al. Body size and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(11):1011–9. 9169910. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009057.

Qian F, Wang S, Mitchell J, McGuffog L, Barrowdale D, Leslie G, et al. Height and Body Mass Index as Modifiers of Breast Cancer Risk in BRCA 1/2 Mutation Carriers: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(4):350–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy132 PMID: 30312457; PMCID: PMC6449171.

Kotsopoulos J, Olopado OI, Ghadirian P, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, et al. Changes in body weight and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(5):R833–43. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1293 Epub 2005 Aug 19. PMID: 16168130; PMCID: PMC1242151.

Kim SJ, Huzarski T, Gronwald J, Singer CF, Møller P, Lynch HT, et al. Prospective evaluation of body size and breast cancer risk among BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):987–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy039 PMID: 29547931; PMCID: PMC6005062.

Manders P, Pijpe A, Hooning MJ, Kluijt I, Vasen HF, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. Body weight and risk of breast cancer in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(1):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-1120-8 Epub 2010 Aug 21. PMID: 20730487.

Zhang SM, Lee IM, Manson JE, Cook NR, Willett WC, Buring JE. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in the Women’s health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(6):667–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwk054 Epub 2007 Jan 4. PMID: 17204515.

Bennicke K, Conrad C, Sabroe S, Sørensen HT. Cigarette smoking and breast cancer. BMJ. 1995;310(6992):1431–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.310.6992.1431 PMID: 7613275; PMCID: PMC2549812.

Narod SA. Modifiers of risk of hereditary breast cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25(43):5832–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1209870 PMID: 16998497.

Li H, Terry MB, Antoniou AC, Phillips KA, Kast K, Mooij TM, et al. Alcohol Consumption, Cigarette Smoking, and Risk of Breast Cancer for BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 Mutation Carriers: Results from The BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(2):368–78. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0546 Epub 2019 Dec 2. PMID: 31792088.

Kehm RD, Genkinger JM, MacInnis RJ, John EM, Phillips KA, Dite GS, et al. Recreational Physical Activity Is Associated with Reduced Breast Cancer Risk in Adult Women at High Risk for Breast Cancer: A Cohort Study of Women Selected for Familial and Genetic Risk. Cancer Res. 2020;80(1):116–25. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.

van Erkelens A, Derks L, Sie AS, Egbers L, Woldringh G, Prins JB, et al. Lifestyle Risk Factors for Breast Cancer in BRCA 1/2-Mutation Carriers Around Childbearing Age. J Genet Couns. 2017;26(4):785–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-016-0049-4 Epub 2016 Dec 13. PMID: 27966054; PMCID: PMC5502067.

Dennis J, Krewski D, Côté FS, Fafard E, Little J, Ghadirian P. Breast cancer risk in relation to alcohol consumption and BRCA gene mutations--a case-only study of gene-environment interaction. Breast J. 2011;17(5):477–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01133.x Epub 2011 Jul 15. PMID: 21762248. .CAN-19-1847. Epub 2019 Oct 2. PMID: 31578201; PMCID: PMC7236618.

Ghadirian P, Lubinski J, Lynch H, Neuhausen SL, Weber B, Isaacs C, et al. Smoking and the risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA mutations. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(3):413–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.20106 Erratum in: Int J Cancer. 2005 May 10;114(6):1016. Freidman, Eitan [corrected to Friedman, Eitan]. PMID: 15095307.

Ko KP, Kim SJ, Huzarski T, Gronwald J, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, et al. Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. The association between smoking and cancer incidence in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(11):2263–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31257 Epub 2018 Jan 25. PMID: 29330845; PMCID: PMC6020833.

Ginsburg O, Ghadirian P, Lubinski J, Cybulski C, Lynch H, Neuhausen S, et al. Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Smoking and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 carriers: an update. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114(1):127–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-008-9977-5 Epub 2008 May 16. PMID: 18483851; PMCID: PMC3033012.

McGuire V, John EM, Felberg A, Haile RW, Boyd NF, Thomas DC, et al. Whittemore AS; kConFab Investigators. No increased risk of breast cancer associated with alcohol consumption among carriers of BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutations ages <50 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(8):1565–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0323 PMID: 16896052.

Yager JD, Davidson NE. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(3):270–82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra050776 PMID: 16421368.

Cavalieri E, Frenkel K, Liehr JG, Rogan E, Roy D. Estrogens as endogenous genotoxic agents--DNA adducts and mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000;27(27):75–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024247 PMID: 10963621.

Yoshida K, Miki Y. Role of BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 as regulators of DNA repair, transcription, and cell cycle in response to DNA damage. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(11):866–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02195.x PMID: 15546503.

Schrijver LH, Olsson H, Phillips KA, Terry MB, Goldgar DE, Kast K, et al. Oral Contraceptive Use and Breast Cancer Risk: Retrospective and Prospective Analyses From a BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 Mutation Carrier Cohort Study. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(2):pky023. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pky023 PMID: 31360853; PMCID: PMC6649757.

Lee E, Ma H, McKean-Cowdin R, Van Den Berg D, Bernstein L, Henderson BE, et al. Effect of reproductive factors and oral contraceptives on breast cancer risk in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers and noncarriers: results from a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17(11):3170–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0396 PMID: 18990759.

Plant AL, Benson DM, Smith LC. Cellular uptake and intracellular localization of benzo(a)pyrene by digital fluorescence imaging microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1985;100(4):1295–308. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.100.4.1295.

Shu HP, Bymun EN. Systemic excretion of benzo(a)pyrene in the control and microsomally induced rat: the influence of plasma lipoproteins and albumin as carrier molecules. Cancer Res. 1983;43(2):485–90.

Hecht SS. Tobacco smoke carcinogens and breast cancer. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2002;39(2-3):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/em.10071.

Morris JJ, Seifter E. The role of aromatic hydrocarbons in the genesis of breast cancer. Med Hypotheses. 1992;38(3):177–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9877(92)90090-Y.

MacNicoll AD, Easty GC, Neville AM, Grover PL, Sims P. Metabolism and activation of carcinogenic polycyclic hydrocarbons by human mammary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;95(4):1599–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-291X(80)80081-7.

el-Bayoumy K. Environmental carcinogens that may be involved in human breast cancer etiology. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:585–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank Athina Papa for the language editing.

Funding

Not applicable for that section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Antonella Daniele and Angelo Virgilio Paradiso creators of the review and wrote the paper; Carla Minoia, Miriam Dellino and Salvatore Pisconti parteciped in data collection, Patrizia Pasanisi, Margherita Patruno and Maria Digennaro parteciped in critical revision of manuscript, Rosa Divella, Porzia Casamassima and Eufemia Savino parteciped in study design. All authors approved final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for that section.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Daniele, A., Divella, R., Pilato, B. et al. Can harmful lifestyle, obesity and weight changes increase the risk of breast cancer in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers? A Mini review. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 19, 45 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00199-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00199-6