Abstract

Background

Endometrial cancer is often the sentinel cancer in women with Lynch syndrome, among which endometrioid endometrial cancer is the most common. We found a Korean case of uterine carcinosarcoma associated with Lynch syndrome. And we reviewed 27 Korean women with endometrial cancer associated with Lynch syndrome already released in case report so far.

Case presentation

The proband, a 45-year-old Korean woman received treatment for endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Her older sister and niece were treated for endometrioid adenocarcinoma and carcinosarcoma, respectively. Family history met the Amsterdam II criteria and immunohistochemical analysis revealed a loss of MLH1 and PMS2. They all harbored a previously unreported germline likely pathogenic variant in c.1367delC in MLH1. They underwent staging operations including total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic/paraaortic lymph node dissection, and washing cytology. All three women were healthy without evidence of relapse for over 4 years.

Conclusion

This report indicates a novel germline c.1367delC variant in MLH1, and presents a Korean case of uterine carcinosarcoma associated with Lynch syndrome. Furthermore, the c.1757_1758insC variant in MLH1 was suggested as a founder mutation in Lynch syndrome in Korean women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes. This condition is associated with malignant tumors in various extra-colonic sites including the uterus, ovaries, stomach, small intestine, urothelium, biliary tract, pancreas, brain, and skin. Uterine endometrial cancer is the second most common manifestation in HNPCC [1].

Tumorigenesis occurs owing to inactivating mutations in genes encoding essential proteins in the MMR pathway, which are primarily associated with the repair of replication errors. Human MMR genes including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, and PMS2 are associated with this condition. In Lynch syndrome, approximately 50% of mutations occur in MLH1, 40% occur in MSH2, and 7% occur in MSH6.2 Fewer mutations have been reported in PMS2 [2]. However, the prevalence of MMR gene mutations in Korean women, especially in endometrial cancer-associated Lynch syndrome, is unclear. Thus far, 20 mutations in MMR genes in 24 cases of Korean women with endometrial cancer associated with Lynch syndrome have been reported.

For effective preventive management, identification of families with Lynch syndrome is very important. Herein, we assessed a Korean family with Lynch syndrome and identified a novel germline MLH1 variant. Moreover, this study summarizes germline variants in MMR genes in 27 Korean women with endometrial cancer associated with Lynch syndrome.

Case report

The proband marked III-7 (Fig. 1), a 45-year-old pre-menopausal woman and her elder sister, a 51-year-old premenopausal woman marked III-6 (Fig. 1), presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Pathological examination revealed endometrioid adenocarcinoma and imaging examination revealed that the disease was confined to the endometrial cavity. They underwent staging operations including total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic/paraaortic lymph node dissection, and washing cytology. Her niece marked IV-5 (Fig. 1), a 28-year-old woman, was diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma and received 500 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate daily for 3 months to preserve fertility. However, the disease progressed and the aforementioned staging operations were performed for the niece. Histological examination revealed carcinosarcoma with lymph node metastasis. She received chemoradiation therapy with cisplatin-ifosfamide. All three women were healthy without evidence of relapse for over 4 years.

Their family history revealed a typical clustering of cancer. Five first- and second-degree relatives had also died of colon, pancreatic, or uterine cancer and four other relatives had also developed stomach, colon, or uterine cancer (Fig. 1). Ten of her relatives were diagnosed with Lynch syndrome-associated cancers across four generations. Therefore, this family meets the Amsterdam II criteria.

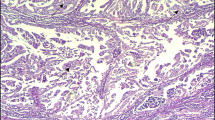

Immunohistochemical analysis of MMR protein was performed in biopsy specimens of patients. MLH1 and PMS2 expression were negative in the proband shown and her niece, indicating the loss of these proteins (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 were deficient in the proband’s elder sister (Fig. 2b). To identify Lynch syndrome, MLH1 (reference sequence: NM 000249) and MSH2 (reference sequence: NM 000251) variants were evaluated using genomic DNA from peripheral blood of the proband. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and Sanger sequencing were performed for genetic analysis (Seoul clinical laboratories, ABI veriti for PCR amplification, ABI 3500DX for Sanger sequencing). A c.1367delC variant was detected in MLH1 (Fig. 3); however, no variant was detected in MSH2. We performed genetic analyses for the MLH1 variant among the proband’s relatives and III-2, III-6, IV-5, and IV-11 displayed the same MLH1 variant (Fig. 1).

Analysis of mismatch repair genes in the proband and proband’s elder sister. A Proband’s immunohistochemical analysis for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 revealed negative staining for MLH1 and PMS2, representing the loss of expression. B Results of immunohistochemical analysis of the proband’s elder sister showed negative staining for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2

Discussion

Herein, we report the case of three Korean women with endometrial malignancy from a family with Lynch syndrome. This study is the first to report the c.1367delC variant in MLH1 in Lynch syndrome. Moreover, one of three women had uterine carcinosarcoma, which, to our knowledge, is a novel finding in relation to Lynch syndrome in Korean women.

This c.1367delC variant corresponds to a likely pathogenic variant according to standards and guidelines of American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics for the interpretation of sequence variants. For the c.1367delC variant to be classified as pathogenic, further studies such as functional analysis are needed.

We reviewed literatures and summarized germline mutations in MMR genes in 27 Korean women with endometrial cancer associated with Lynch syndrome, including the present three cases (Table 1) [1, 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The average diagnostic age for endometrial cancer was 46.3 years. The MLH1 mutation was the primarily harbored mutation (51.9%, n = 14), other mutations included those in MSH2 (37.0%, n = 10) and MSH6 (11.1%, n = 3). These mutation rates are concurrent with those reported previously for Lynch syndrome in Caucasian individuals (n = 448) [2]. However, compared with the mutations rates for colorectal cancers associated with Lynch syndrome in 44 Korean individuals, wherein only four patients with endometrial cancers were included and reported mutation rates of 70.5, 22.7, and 6.8% in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6, respectively [1], the MLH1 mutation rate is greater in colon cancer than in endometrial cancer associated with Lynch syndrome.

The c.1367delC variant in MLH1 in this family has not been previously reported in studies published in English according to our literature survey. Herein, the two variants c.1367delC and c.1780_1781insC in MLH1 were respectively harbored in three women belonging to the same family. The c.1757_1758insC variant in MLH1 being the most common in the three family members (Table 1) and occurring commonly in colorectal cancer associated with Lynch syndrome (11 of 31 families) [1]. Together, the c.1757_1758insC variant in MLH1 could be suggested to be a founder mutation in Lynch syndrome in Korean individuals rather than in individuals in other countries.

Despite the controversy regarding the dominant histologic subtype of endometrial cancer in Lynch syndrome, endometrioid adenocarcinoma is most frequent [14], and a few cases of nonendometrioid adenocarcinoma have been reported [15]. In the present literature review, histological characteristics were determined in 12 cases and three women had non-endometrioid type tumors including serous adenocarcinoma, dedifferentiated adenocarcinoma, and carcinosarcoma. This is the first report of a case of carcinosarcoma associated with Lynch syndrome in Korean women.

In conclusion, this study reports a novel likely pathogenic variant c.1367delC in MLH1 in Lynch syndrome and the case of Korean women with uterine carcinosarcoma associated with Lynch syndrome.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated or analysed during this study are available from electronic medical record of Chung-Ang university hospital. But restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. The data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Chung-Ang university hospital.

Abbreviations

- HNPCC:

-

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

- MMR:

-

Mismatch repair

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Shin YK, Heo SC, Shin JH, Hong SH, Ku JL, Yoo BC, et al. Germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 in Korean hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer families. Hum Mutat. 2004;24(4):351.

Peltomaki P, Vasen H. Mutations associated with HNPCC predisposition — update of ICG-HNPC5C/INSiGHT mutation database. Dis Markers. 2004;20(4-5):269–76.

Han HJ, Maruyama M, Baba S, Park JG, Nakamura Y. Genomic structure of human mismatch repair gene, hMLH1, and its mutation analysis in patients with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(2):237–42.

Shin SH, Yu EJ, Lee YK, Song YS, Seong MW, Park SS. Characteristics of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer patients with double primary cancers in endometrium and colorectum. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58(2):112–6.

Yoon SN, Ku JL, Shin YK, Kim KH, Choi JS, Jang EJ, et al. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in endometrial cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(5):1077–81.

Lim MC, Seo SS, Kang S, Seong MW, Lee BY, Park SY. Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer/Lynch syndrome in Korean patients with endometrial cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(12):1121–7.

Hwang IT. A novel germline mutation of hMLH1 in a Korean hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer family. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1313–8.

Lee HJ, Choi MC, Jang JH, Jung SG, Park H, Joo WD, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of double primary endometrial and colorectal cancers in a single institution. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(5):944–50.

Heo EJ, Park JM, Lee EH, Lee HW, Kim MK. A case of Perimenopausal endometrial Cancer in a woman with MSH2 Germline mutation. J Menopausal Med. 2013;19(3):143–6.

Lee JY, Kim HJ, Lee EH, Lee HW, Kim JW, Kim MK. One case of endometrial cancer occurrence: over 10 years after colon cancer in Lynch family. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56(6):408–11.

Yuan Y, Han H-J, Zheng S, Park JG. Germline mutations of hMLH1 and hMSH2 genes in patients with suspected hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and sporadic early-onset colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(4):434–40.

Bae SY, Kim MK, Kim B-G. Endometrial cancer six years after colon cancer in Lynch syndrome: single institution case in Korea. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(11):870.

Lee HJ, Lee MH, Choi MC, Jung SG, Joo WD, Kim TH, et al. Case report of menopausal woman diagnosed with endometrial Cancer after Colon Cancer with Germline mutation in MSH6 in Korea. J Menopausal Med. 2017;23(1):69–73.

Broaddus RR, Lynch HT, Chen LM, Daniels MS, Conrad P, Munsell MF, et al. Pathologic features of endometrial carcinoma associated with HNPCC: a comparison with sporadic endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106(1):87–94.

Clarke BA, Cooper K. Identifying Lynch syndrome in patients with endometrial carcinoma: shortcomings of morphologic and clinical schemas. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19(4):231–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1D1A1B03033972).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJ analyzed and interpreted the patient data and wrote draft of this paper. HR analyzed genetic data. MK performed the histological examination of the uterus. EJ designed and conceptualized this work and revised the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Subjects have given their written informed consent to publish their case. This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chung-Ang university hospital. (approval No. 1990-001-001).

Consent for publication

No competing financial interests exist.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, YJ., Kim, H.R., Kim, M.K. et al. A novel germline mutation in hMLH1 in three Korean women with endometrial cancer in a family of Lynch syndrome: case report and literature review. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 19, 28 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00185-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00185-y