Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis and condylar resorption of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) has rarely been reported in children as consequence of otologic disease. We describe the management of a case in a 9-year-old female as long-term complication of an otomastoiditis and review the literature currently available on this topic.

Case presentation

A nine-years-old female patient referred to Emergency Room of Bambino Gesù Children’s Research Hospital, IRCCS (Rome,Italy) for an acute pain in the left preauricular area and reduced mandibular movements. In the medical history an otomastoiditis and periorbital cellulitis was reported at the age of six with complete remission of symptoms after antibiotic treatment. No recent history of facial trauma and no previous orthodontic treatment were reported. She was referred to a pediatric dentist that conducted a clinical examination according to the Diagnostic Criteria of Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) and was diagnosed with bilateral myalgia of the masticatory muscles and arthralgia at the level of the left TMJ. Then, a complete diagnostic path was performed that included multidisciplinary examinations by a rheumatologist, infectious disease specialist, ear nose and throat (ENT) doctor, a maxillofacial surgeon and a medical imaging specialist. Differential diagnosis included juvenile idiopathic arthritis, idiopathic condylar resorption, trauma, degenerative joint disease, neurological disease. Finally, unilateral post-infective osteoarthritis of the left TMJ with resorption of mandibular condyle was diagnosed. The patient went through a pharmacological therapy with paracetamol associated to counselling, jaw exercises and occlusal bite plate. After 1 month, the patient showed significant reduction of orofacial pain and functional recovery that was confirmed also one-year post-treatment. The novelty of this clinical case lies in the accurate description of the multidisciplinary approach with clinical examination, the differential diagnosis process and the management of TMD with conservative treatment in a growing patient.

Conclusions

Septic arthritis of temporomandibular joint and condylar resorption were described as complications of acute otitis media and/or otomastoiditis in children. We evidenced the importance of long-term follow-up in children with acute media otitis or otomastoiditis due to the onset of TMJ diseases. Furthermore, in the multidisciplinary management of orofacial pain the role of pediatric dentist is crucial for the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway to avoid serious impairment of mandibular function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Post-infective osteoarthritis is a rare finding in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) where the infection can spread via the haematogenous route or can be transmitted by contiguity [1, 2]. Septic osteoarthritis of the TMJ is a rare complication of acute otitis media and otomastoiditis in children [3,4,5,6]. Clinical presentation of septic osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint varies from one individual to another, it may include trismus, torcicollis, impaired function of the mandible, fever, pre-auricular swelling, pain [3]. Trismus, condylar resorption, pain and impaired function are common findings in other inflammatory conditions of the temporomandibular joints such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, idiopathic condylar resorption, chronic mandibular osteomyelitis and other degenerative joint diseases [7,8,9,10,11]. No previous study reported clinical examination according to the DC/TMD in children affected by post-infective osteoarthritis in the TMJ area. Differential diagnosis may be difficult to perform and addressing pain and function impairment is the main goal. A correct diagnosis is crucial for accurate and effective treatments [7, 10].

In this article, we present the management of a 9 years-old female patient with orofacial pain and impaired mandibular function due to secondary mandibular condylar resorption as a complication of an otomastoiditis. We also reviewed literature of otogenic cases of TMJ septic arthritis in children, published in English since 2000, in order to discuss long-term consequences and management strategies for the improvement of mandibular function.

Search Strategy.

To identify relevant studies from 2000 until today in English language, we systematically searched MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

The search strategy was carried out without language restrictions until 31st August 2021. In PubMed, the following search strategy was used: ((“Temporomandibular Joint”[Mesh]) AND “Arthritis, Infectious”[Mesh]); (“Temporomandibular Joint Disorders”[Mesh]) AND “Arthritis, Infectious”[Mesh]; (“Temporomandibular Joint Disorders”[Mesh]) and septic arthritis (as single words).

In EMABSE, the following search strategy was used: ((Temporomandibular Joint Disorders OR Temporomandibular) AND (Arthritis, Infectious OR septic arthritis).

In Cochrane the following search strategy was used: Temporomandibular Joint Disorders and septic arthritis. All the works whose pathology was not of otological origin were excluded from the research.

The keywords used were: child, osteoarthritis, temporomandibular disorders and temporomandibular joint.

Case presentation

A nine-years-old female patient referred to the Emergency Room of Bambino Gesù Children’s Research Hospital, IRCCS (Rome, Italy) for an acute pain in preauricular area and severe impairment of mandibular function.

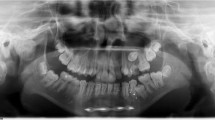

During the medical history, the mother of the patient reported an otomastoiditis and periorbital cellulitis at the age of six recovered after antibiotic treatment with complete remission of symptoms. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) performed 2 years earlier showed condylar symmetry, normal dental formula and absence of significant radiographic alterations (Fig. 1A-C). The patient was referred to maxillofacial surgeon and dental specialist.

The maxillofacial surgeon reported a condition of inflammation with functional limitation during mouth opening and prescribed paracetamol and antibiotic (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) assumption .

At the Dentistry Unit, the patient had complained a pulsating and intermittent pain (Visual Analogic Scale = 9) on the left side located in the preauricular area, at the gonial angle region and in the sub mandibular area for about 4 months. Further investigations included the DC/TMD symptom questionnaire and clinical examination [12, 13]. At the extra oral clinical evaluation, there is no evidence of significant facial asymmetry on the frontal view and the facial profile was orthognathic. At the clinical intraoral examination the patient presented a Class I malocclusion in mixed dentition, lower dental midline shift to the right and absence of any other relevant alteration. (Fig. 2A-C). Dynamic evaluation of the mandibular function showed reduced mouth opening (31 mm) with left uncorrected deviation of the mandible during mouth opening (Fig. 3A) and protrusion, limited right laterotrusion (6 mm) (Fig. 3B) compared to the left one (9 mm) (Fig. 3C). The clinical examination led to the diagnosis of bilateral myalgia and arthralgia of the left temporomandibular joint according to the DC/TMD [11, 12]. A maxillofacial CT showed the left condyle significantly eroded (Fig. 4C) when compared to the previous CT scan. The patient received counselling and instructions about physiotherapy [14,15,16] and pain management continued by administration of paracetamol as needed.

Differential diagnosis included onset of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, idiopathic condylar resorption, osteoarthritis, osteonecrosis. In order to perform a complete diagnosis, the patient was referred to the rheumatologist who performed blood test and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of both temporomandibular joints. This last confirmed morphological alteration of the left condyle and the glenoid fossa with flattening of the articular eminence, presence of mild inflammation and reduced thickness of the disk that was still correctly in place.

At the end of diagnostic path, the diagnosis was post-infective osteoarthritis of the left temporomandibular joint linked to the previous otomastoiditis. A customised passive rigid bite plate was realised, and bedtime use was prescribed (Fig. 5). One month later the full clinical examination according to DC/TMD revealed decrease of pain (Visual Analogic Scale = 4), persistence of arthralgia of the left temporomandibular joint, improvement of the mouth opening (40 mm), persistence of the left uncorrected deviation of the mandible during mouth opening and limited right laterotrusion. Three months later the patient reported improvement in the mandibular function and finally absence of pain (Visual Analogic Scale = 0). One year later the MRI showed absence of further alteration of the left condyle and the temporal bone (Fig. 6) and sensible reduction of the inflammatory infiltration on the left temporomandibular joint . During the last check up the patient showed an additional improvement of the mouth opening (43 mm) and the right and the left laterotrusion movements remain stable but without pain (Fig. 7). The follow up of the patient passed to 6 months in order to evaluate the need of orthodontic therapy closer to the pubertal spurt.

Discussion and conclusions

We identified nine articles [3,4,5,6,7, 17,18,19,20] on TMJ septic arthritis of otogenic origin in children published since 2000 in English literature. Seven articles were case reports [3, 5, 7, 17,18,19,20,21] and they did not evidence any long-term consequences of septic arthritis of TMJ. On the other hand, Luscan et al. [3] observed in a prospective study of 45 patients that 1 patient had an erosion of the temporomandibular condyle and 2 patients presented clinical diagnosis of TMJ ankylosis as long-term complication, 4 and 16 months after otomastoiditis.

Burgess et al. [6] reported nine pediatric cases of otogenic septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in a retrospective study and showed that six patients presented a late ankylosis of TMJ from 0.5 to 4 years after the initial middle ear infection.

In this article, we present the management of a 9 years-old female patient with reduced mandibular movement, orofacial pain and condylar resorption that arose 2 years later an otomaoiditis.

The clinical presentation of our patient was characterised by many overlapping signs and symptoms making diagnosis difficult to perform at a glance. The patient had no history of trauma and the left otomastoiditis reported occurred about 2 years before the first symptoms of temporomandibular joint involvement. Differential diagnosis is crucial in such cases, where growing patients are involved, because the sequelae of temporomandibular disease may influence growth and mandibular function leading to severe facial asymmetry and permanent mandibular impairment [21, 22]. Dental practitioners need to be able to formulate differential diagnosis hypothesis and to address the patient to the right specialists. Moreover, conservative treatment, including counselling and physiotherapy, helps the patients in managing the acute situation with minimal risks preventing complications such as fibrosis and ankyloses of the temporomandibular joint [14, 15]. To date there is no consensus on treatment of post-infectious osteoarthritis [3]. Nevertheless, there is evidence for physiotherapy in being effective in most of TMDs, improving mobility of the temporomandibular joint and preventing adherences and ankyloses [14, 15]. The bone remodelling resulting from osteoarthritis is a permanent alteration of bone structure. However, condylar cartilage has itself a potential for bone modification and in growing patients there is as well a potential for condylar growth [23]. Modulation of bone remodelling and residual growth in growing patients [24] can be effective in improving facial symmetry by addressing the condylar asymmetry [21, 25]. In order to start any orthopaedic and orthodontic treatment, the inflammatory condition of the temporomandibular joint has to be under control and the mandible has normal function [21, 25, 26]. It is important to inform the patients and the families about these opportunities and to underline the importance of preserving mandibular function.

In our case, the patient improved mandibular function and full recovery of mouth opening without any pain during mandibular movement. Moreover, the conservative therapy and the use of a nocturnal bite plate helped pain management and were effective in reducing both myalgia and arthralgia of the left temporomandibular joint. The one-year control MRI showed stable bone morphology without progression of bone erosion and with no evidence of inflammation. The patient undergoes regular follow-ups. As soon as the pubertal growth spurt starts, we will consider the opportunity of undergoing orthopaedic treatment with a mandibular asymmetrical activator to address condylar asymmetry.

As previously suggested [6], this case highlights the importance of long-term follow-ups in children with acute media otitis or otomastoiditis due to TMJ disorders that can occur up to 4 years later.

Furthermore, in the multidisciplinary management of orofacial pain the role of the pediatric dentist is crucial for the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway to avoid serious impairment of mandibular function.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing was not applicable to this case report because no datasets were generated or analysed during the study.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- DC/TMD:

-

Diagnostic Criteria of Temporomandibular Disorders

- ENT:

-

Ear nose and throat

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- TMD:

-

Temporomandibular Disorders

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

References

Constant M, Nicot R, Maes JM, Raoul G, Ferri J. Temporomandibular joint septic arthritis with secondary condylar resorption. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac Chir Orale. 2016;117(4):294–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revsto.2016.07.018.

Frojo G, Komarraju Tadisina K, Shetty W, Lin AY. temporomandibular joint septic arthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(1):e1648. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000001648 eCollection 2018 Jan.

Castellazzi ML, Senatore L, Di Pietro G, Pinzani R, Torretta S, Coro I, et al. Otogenic temporomandibular septic arthritis in a child: a case report and a review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0682-2.

Luscan R, Belhous K, Simon F, Boddaert N, Couloigner V, Picard A, et al. TMJ arthritis is a frequent complication of otomastoiditis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44(12):1984–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2016.09.015.

Dubron K, Meeus J, Grisar K, Desmet S, Dormaar T, Spaey Y, et al. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint after acute otitis media in a child. Quintessence Int. 2017;48(10):809–13. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a39032.

Burgess A, Celerier C, Breton S, Van den Abbeele T, Kadlub N, Leboulanger N, et al. Otogenic temporomandibular arthritis in children. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(5):466–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2016.3977.

Gayle EA, Young SM, McKenna SJ, McNaughton CD. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: case reports and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):674–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.01.034.

Ernberg M. The role of molecular pain biomarkers in temporomandibular joint internal derangement. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44(6):481–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12480.

Robinson WH, Lepus CM, Wang Q, Raghu H, Mao R, Lindstrom TM, et al. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(10):580–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.136.

Antao C, Dinkar A, Khorate M, Raut DS. Chronic diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis of the mandible. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2019;9(1):188. https://doi.org/10.4103/ams.ams_257_18.

Wolford LM. Idiopathic condylar resorption of the temporomandibular joint in teenage girls (cheerleaders syndrome). Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2001;14(3):246–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2001.11927772.

Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, et al. International RDC/TMD consortium network, international association for dental research; orofacial pain special interest group, International Association for the Study of Pain. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the international RDC/TMD consortium network* and orofacial pain special interest group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6–27. https://doi.org/10.11607/jop.1151.

Peck CC, Goulet JP, Lobbezoo F, Schiffman EL, Alstergren P, Anderson GC, et al. Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(1):2–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12132.

Durham J, Al-Baghdadi M, Baad-Hansen L, Breckons M, Goulet JP, Lobbezoo F, et al. Self-management programmes in temporomandibular disorders: results from an international Delphi process. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43(12):929–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12448.

Lindfors E, Arima T, Baad-Hansen L, et al. Jaw exercises in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders-an international modified Delphi study. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2019;33(4):389–98. https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.2359.

Bucci R, Lobbezoo F, Michelotti A, Koutris M. Two repetitive bouts of intense eccentric-concentric jaw exercises reduce experimental muscle pain in healthy subjects. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(8):575–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12656.

Hadlock TA, Ferraro NF, Rahbar R. Acute mastoiditis with temporomandibular joint effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(1):111–2. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhn.2001.115664.

Amos MJ, Patterson AR, Worrall SF. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in a 6-year-old child. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(3):242–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.04.019.

Bast F, Collier S, Chadha P, Collier J. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint as a complication of acute otitis media in a child: a rare case and the importance of real-time PCR for diagnosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(11):1942–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.08.014.

Tsai C, Deramo J, Shen X, Vandiver K, Mittal V. Luc's abscess and temporomandibular joint septic arthritis: two rare sequelae of acute otitis media. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020 May;36(5):e285–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001348.

Stoustrup P, Pedersen TK, Nørholt SE, Resnick CM, Abramowicz S. Interdisciplinary management of dentofacial deformity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2020;32(1):117–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2019.09.002.

Kang JH, Yang IH, Hyun HK, Lee JY. Dental and skeletal maturation in female adolescents with temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44(11):879–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12547.

Shen G, Darendeliler MA. The adaptive remodeling of condylar cartilage-a transition from chondrogenesis to osteogenesis. J Dent Res. 2005;84(8):691–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910508400802.

Martina R, Cioffi I, Galeotti A, Tagliaferri R, Cimino R, Michelotti A, et al. Efficacy of the Sander bite-jumping appliance in growing patients with mandibular retrusion: a randomized controlled trial. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2013;16(2):116–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr.12013.

Stoustrup P, Küseler A, Kristensen KD, Herlin T, Pedersen TK. Orthopaedic splint treatment can reduce mandibular asymmetry caused by unilateral temporomandibular involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35(2):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjr116.

Carrasco R. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis overview and involvement of the temporomandibular joint: prevalence, systemic therapy. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2015;27(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2014.09.001.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Mr. Gabriele Bacile (Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital IRCCS, Rome,Italy) for the image processing and dental technician Mr. Patrizio Evangelista (Orthonet, Rome, Italy) for the realization of the oral device.

Conflict of interest

There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and authorship of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PF and EA performed the review of literature and equally contributed to the final writing of the manuscript. EA and GV managed the patients during the first visit and follow-ups. ACV contributed in the multidisciplinary path and to the revision of the manuscript. DB helped in managing and interpreting all diagnostic images related to the present case report. AG is the Responsible of the Dentistry Unit of Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital and supervised the entire process, from clinical examination to writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, as it is a case report.

Consent for publication

An informed consent for the publication of this case report was obtained from the patient’s parents.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Festa, P., Arezzo, E., Vallogini, G. et al. “Multidisciplinary management of post- infective osteoarthritis and secondary condylar resorption of temporomandibular joint: a case report in a 9 years-old female patient and a review of literature”. Ital J Pediatr 48, 62 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01255-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01255-0