Abstract

Background

Severe hypercalcemia is rare in newborns; even though often asymptomatic, it may have important sequelae. Hypophosphatemia can occur in infants experiencing intrauterine malnutrition, sepsis and early high-energy parenteral nutrition (PN) and can cause severe hypercalcemia through an unknown mechanism. Monitoring and supplementation of phosphate (PO4) and calcium (Ca) in the first week of life in preterm infants are still debated.

Case presentation

We report on a female baby born at 29 weeks’ gestation with intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) experiencing sustained severe hypercalcemia (up to 24 mg/dl corrected Ca) due to hypophosphatemia while on phosphorus-free PN. Hypercalcemia did not improve after hyperhydration and furosemide but responded to infusion of PO4. Eventually, the infant experienced symptomatic hypocalcaemia (ionized Ca 3.4 mg/dl), likely exacerbated by contemporary infusion of albumin. Subsequently, a normalization of both parathyroid hormone (PTH) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was observed.

Conclusions

Although severe hypercalcemia is extremely rare in neonates, clinicians should be aware of the possible occurrence of this life-threatening condition in infants with or at risk to develop hypophosphatemia. Hypophosphatemic hypercalcemia can only be managed with infusion of PO4, with strict monitoring of Ca and PO4 concentrations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Severe hypercalcemia in newborns is a rare event and, even though generally well tolerated, it may be lethal or cause several complications, such as bradycardia, seizures, renal and brain calcifications [1,2,3,4,5]. Therefore, appropriate investigations and treatment strategies should be promptly established.

Extremely (E-) or very (V-) low birth weight (LBW) neonates, especially if born small for gestational age (SGA) are more prone to develop hypophosphatemic hypercalcemia [1], due to a complex combination of factors, such as depleted phosphate (PO4) stores, renal immaturity, increased infection risk and early high-energy parenteral nutrition (PN) [2,3,4]. However, due to the rarity of the condition, the exact mechanism underlying the association between hypophosphatemia and severe hypercalcemia is still poorly understood.

Optimal monitoring and nutritional strategies to prevent early hypophosphatemia in premature infants are still debated. Indeed, inadequate supply of PO4 in the first days of life represent a relevant issue [2, 4], particularly in countries like Italy, where the main PO4 source for PN (D-Fructose-1,6-diphosphate) is no longer available.

We report on a SGA ELBW neonate experiencing severe hypercalcemia due to hypophosphatemia with the aim of discussing pathogenesis, treatment and prevention of this rare condition.

Case presentation

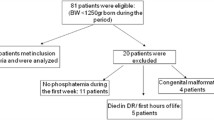

A female baby was born at 29 weeks’ gestation by coesarian section because of placental vascular dysfunction and severe intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), weighing 600 g (SGA). Her mother was receiving 2000 IU of vitamin D3 and 450 mg of magnesium per day and had no electrolytes abnormalities. Family history was negative for calcium (Ca) metabolism disorders. She developed respiratory distress necessitating mechanical ventilation for 2 days, followed by non-invasive ventilation. Spontaneous closure of ductus arteriosus was observed. C-reactive protein was raised at 12 h of life, but normalized 3 days after starting antibiotics. Blood culture was negative. She received PO4-free total PN for 2 days, containing amino acids up to 2.5 g/kg/day and Ca 0.5 mmol/kg/day. On day 3 of life, minimal enteral feeding was started using boluses of plain expressed breast milk (EBM), with gradual increase in the volume. Over the first 5 days of life, serum Ca concentrations were normal (between 7.8 mg/dl and 8.5 mg/dl).

Since day 6, she became hypercalcemic and Ca concentrations rose progressively (Fig. 1). Despite decrease and eventual discontinuation of parenteral Ca and Vitamin D delivery, corrected Ca concentrations reached a peak of 24 mg/dl. Diagnostic work-up revealed PO4 1.4 mg/dl (nv 4.4–8), magnesium 2.2 mg/dl (nv 1.7–2.5), sodium 137 mmol/L, potassium 3.8 mmol/L, albumin 1.8 g/dl (nv 3.3–4.5), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 377 IU/L (nv 77–375), creatinine 1.06 mg/dl, urea 0.75 g/l, urine Ca/creatinine ratio 2.8 mmol/mmol (nv 0.09–2.2), urine PO4/creatinine ratio 1 mmol/mmol (nv 1.2–19), calcitonin 27 pg/ml (nv 0.8–9.9), normal thyroid function and suppressed parathyroid hormone (PTH) 4.8 pg/ml (nv 7.5–53.5), suggesting PTH-independent hypercalcemia. The infant was asymptomatic, except for mild polyuria.

Hypercalcemia did not improve after hyperhydration (220 ml/kg/day) and IV furosemide (1.5 mg/kg every 6 h) (Fig. 1). Given the rather small amount of EBM (16 ml/day), enteral nutrition was continued. Introduction of sodium glycerophosphate in the PN solution (PO4 80 mg/kg/day) resulted in a prompt decrease in Ca concentrations to 10 mg/dl within 24 h, with transient symptoms of hypocalcaemia (ionized Ca 3.4 mg/dl), which could be in part favored by contemporary infusion of albumin (Fig. 1). Therefore, the rate of infusion of sodium glycerophosphate was initially lowered and then a balanced infusion of Ca and PO4 was kept, in order to maintain normal Ca and PO4 concentrations. Four days after the introduction of PO4, PTH normalized (41.5 pg/ml, nv 7.5–53.5), while ALP was slightly raised at 788 IU/L, likely due to transient hypocalcemia. Within 3 weeks, her bone profile fully normalized (ALP 473 IU/L; PTH 39 pg/ml) and, due to good tolerance to formula milk feeds, Ca and PO4 supplements were discontinued. The baby had no evidence of renal or brain calcifications on repeated ultrasound scans nor bone lesions on x-ray.

Discussion and conclusions

We report on a SGA ELBW neonate experiencing sustained severe hypercalcemia since the first week of life, associated with hypophosphatemia while on PN. This case provides insights on the mechanisms of Ca dysregulation in hypophosphatemic infants, emphasizing appropriate investigations, prevention and treatment aspects of this rare condition.

Severe hypercalcemia, defined as total serum Ca > 14 mg/dL [6], is uncommon in newborns. Although often asymptomatic, it may have important sequelae, such as brain calcifications and nephrocalcinosis possibly leading to distal tubular dysfunction, urinary stones, and renal failure [5]. Therefore, this condition requires prompt investigations and therapeutic interventions.

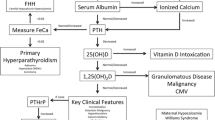

Neonatal hypercalcemia recognizes mainly PTH-independent causes [7, 8], such as sepsis [7], iatrogenic (drugs, vitamin A intoxication or excess Ca intake), maternal [9] or neonatal Vitamin D excess (including subcutaneous fat necrosis, hypophosphatemia, excess intake, and granulomatous diseases), congenital syndromes (eg hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, hypophosphatasia, blue diaper syndrome, Williams syndrome, Jansen metaphyseal chondrodysplasia), severe dysthyroidism or idiopathic [8].

In our case, the late onset and the persistence of severe hypercalcemia despite no administration of Ca and Vitamin D, along with low PO4 concentrations indicate hypophosphatemia as a key pathogenic factor. The mechanisms by which hypophosphatemia can cause hypercalcemia are not completely understood. Inhibition of the secretion of FGF23, leading to increased activity of 1-alfa hydroxylase with production of 1,25(OH)2D [8] or alternatively excess release from bones of Ca along with PO4, aiming to compensate the hypophosphatemic state [10] have been proposed.

Data from our patient indirectly support the first theory. In fact, although Vitamin D metabolites were not measured, the infant initially exhibited biochemical signs of hypervitaminosis D, such as low renal phosphate excretion and ALP concentrations not elevated in spite of hypophosphatemia. Moreover, the prompt reduction in calcium concentrations, along with increase in PTH concentrations up to normal values following phosphate infusion may possibly result from reduced production of active vitamin-D metabolites.

Hypophosphatemic hypercalcemia is rare and may occur more frequently in preterm compared to infants at term [8], especially if IUGR/SGA [3, 11, 12], due to a complex combination of factors peculiar to this category of patients. During the third trimester of pregnancy babies exhibit the fastest bone mineralization with great requirements of Ca and PO4 and thus preterm infants have depleted stores of these electrolytes [13]. Moreover, hypophosphatemia in ELBW may be worsen by a sort of re-feeding syndrome [13], also known as Placental Incompletely Restored Feeding syndrome, occurring after introduction of early high-energy PN in babies experiencing intrauterine nutritional deprivation and characterized by intracellular redistribution and increased reprocessing of electrolytes stimulated by insulin [2, 3, 14, 15]. Finally, hypophosphatemia in neonates can be exacerbated by renal losses, sepsis [4] and use of breast milk (which contains relatively large content of Ca compared to PO4) [16]. Although as mentioned above sepsis may also cause hypercalcemia, likely via production of 1,25(OH)2D by extrarenal macrophages [17] or interleukine-induced bone resorption [18], our case suggests poor relevance of this mechanism, as Ca concentrations continued to rise despite the resolution of early-onset sepsis.

Based on these considerations, monitoring and nutritional strategies for prevention of hypophosphatemia appear of paramount importance.

Established monitoring protocols are currently lacking. It has been suggested that, evaluation of PO4 concentration and other biochemical features of re-feeding syndrome should be performed by the third day of life in infants at risk, including VLBW or ELBW neonates receiving PN and repeated every 2 or 3 days [4, 13] or even twice daily before stabilization [19], by using reference ranges appropriate to preterm neonates [20].

Although PO4 supplementation is recommended from the third day of life [19], it has been shown that early introduction (even from the first day of life) in ELBW infants is safe [21,22,23] and results in lower incidence of Ca abnormalities and severe hypercalcemia, as well as in improved Ca retention [16, 24,25,26]. In addition, it might protect from negative effects exerted by hypophosphatemia on energy balance of several organs [4]. Nevertheless, there is a discrepancy between current recommendations on parenteral mineral supplementation. In fact, while guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend PN supply of Ca and PO4 of 1.5–2 mmol/kg/day with Ca:PO4 ratio 1.1–1.3:1 [27], the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition recommend 0.8–2 mmol/kg/day of Ca, and 1–2 mmol/kg/day of PO4, with a Ca: PO4 ratio of 0.8–1:1 [19]. In this respect, several studies [2, 25, 26] indicate that equimolar Ca:PO4 ratio might be more appropriate to meet the great PO4 requirement in the early post-natal period in VLBW infants. Indeed, in the study by Christman et al. [26] hypophosphatemia was detected in up to 34% of babies, despite providing the maximum recommended doses of PO4 for preterm infants with a Ca:PO4 ratio of 1.56. Recently, concern has been raised in countries like Italy where D-Fructose-1,6-diphosphate, the most common PO4 source for PN, is no longer available, and its alternative sodium glycerophosphate has to be imported from abroad. Furthermore, a relationship between amino acid intake and the risk of hypophosphatemia has been noted in preterm infants [2]. Although this suggests that PO4 requirement calculation should also take into account amino acid supply, current evidence is limited to provide clear recommendations in these patients [28].

As far as it concerns treatment, consistent with previous reports [29, 30], our case highlights that hypophosphatemic hypercalcemia does not benefit from treatments commonly used for PTH-indipendent hypercalcemia (such as hyperhydration, furosemide, subcutaneous calcitonin, steroids), but improves dramatically after iv or even oral [29] administration of PO4. Although in theory a drop in ionized calcium may be observed during correction of hypophosphatemia, so far this has never been reported in neonatal hypophosphatemic hypercalcemia. Therefore, given that we used common therapeutic doses of PO4, we hypothesize that contemporary infusion of albumin might have favored symptomatic hypocalcemia. Finally, our case highlights the need for regular check of Ca and PO4 concentrations, even every 2 hours [4], during PO4 infusion.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware of the possible occurrence of life-threatening severe hypercalcemia in infants with or at risk to develop hypophosphatemia. Our case provides additional information regarding the mechanisms of Ca dysregulation in hypophosphatemic infants and confirms that hypophosphatemic hypercalcemia can only be managed with infusion of PO4. Current strategies for monitoring of phosphatemia and for adequate PO4 supplementation of in the first weeks of life in premature infants need to be implemented.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- PN:

-

Parenteral nutrition

- PO4:

-

Phosphate

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- IUGR:

-

Intrauterine growth retardation

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ELBW:

-

Extremely low birth weight

- VLBW:

-

Very low birth weight

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- EBM:

-

Expressed breast milk

References

Ehrenkranz RA. Early nutritional support and outcomes in ELBW infants. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(1):21–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.014.

Bonsante F, Iacobelli S, Latorre G, Rigo J, De Felice C, Robillard PY, et al. Initial amino acid intake influences phosphorus and calcium homeostasis in preterm infants: it is time to change the composition of the early parenteral nutrition. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72880. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072880.

Ichikawa G, Watabe Y, Suzumura H, Sairenchi T, Muto T, Arisaka O. Hypophosphatemia in small for gestational age extremely low birth weight infants receiving parenteral nutrition in the first week after birth. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25(3-4):317–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2011-0485.

Pająk A, Królak-Olejnik B, Szafrańska A. Early hypophosphatemia in very low birth weight preterm infants. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27(6):841–7. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/70081.

Rodd C, Goodyer P. Hypercalcemia of the newborn: etiology, evaluation, and management. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13(6):542–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004670050654.

Bushinsky DA, Monk RD. Electrolyte quintet: calcium. Lancet. 1998;352(9124):306–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12331-5.

McNeilly JD, Boal R, Shaikh MG, Ahmed SF. Frequency and aetiology of hypercalcaemia. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(4):344–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2015-309029.

Stokes VJ, Nielsen MF, Hannan FM, Thakker RV. Hypercalcemic disorders in children. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(11):2157–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3296.

Reynolds A, O'Connell SM, Kenny LC, Dempsey E. Transient neonatal hypercalcaemia secondary to excess maternal vitamin D intake: too much of a good thing. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016219043.

Guellec I, Gascoin G, Beuchee A, Boubred F, Tourneux P, Ramful D, et al. Biological impact of recent guidelines on parenteral nutrition in preterm infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(6):605–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000898.

Brener Dik PH, Galletti MF, Fernández Jonusas SA, Alonso G, Mariani GL, Fustiñana CA. Early hypophosphatemia in preterm infants receiving aggressive parenteral nutrition. J Perinatol. 2015;35(9):712–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.54.

Boubred F, Herlenius E, Bartocci M, Jonsson B, Vanpée M. Extremely preterm infants who are small for gestational age have a high risk of early hypophosphatemia and hypokalemia. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(11):1077–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13093.

Mizumoto H, Mikami M, Oda H, Hata D. Refeeding syndrome in a small-for-dates micro-preemie receiving early parenteral nutrition. Pediatr Int. 2012;54(5):715–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03590.x.

Hearing SD. Refeeding syndrome. BMJ. 2004;328(7445):908–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7445.908.

Marinella MA. The refeeding syndrome and hypophosphatemia. Nutr Rev. 2003;61(9):320–3. https://doi.org/10.1301/nr.2003.sept.320-323.

Hair AB, Chetta KE, Bruno AM, Hawthorne KM, Abrams SA. Delayed introduction of parenteral phosphorus is associated with hypercalcemia in extremely preterm infants. J Nutr. 2016;146(6):1212–6. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.228254.

Lietman SA, Germain-Lee E, Levine MA. Hypercalcaemia in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(4):508–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833b7c23.

Davies JH, Shaw NJ. Investigation and management of hypercalcaemia in children. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(6):533–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2011-301284.

Mihatsch W, Fewtrell M, Goulet O, Molgaard C, Picaud JC, Senterre T. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN working group on pediatric parenteral nutrition. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(6):2360–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.06.950.

Fenton TR, Lyon AW, Rose MS. Cord blood calcium, phosphate, magnesium, and alkaline phosphatase gestational age-specific reference intervals for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-11-76.

Bolisetty S, Pharande P, Nirthanakumaran L, Do TQ, Osborn D, Smyth J, et al. Improved nutrient intake following implementation of the consensus standardized parenteral nutrition formulations in preterm neonates before-after intervention study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):309. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-014-0309-0.

Imel EA, Econs MJ. Approach to the hypophosphatemic patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):696–706. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-1319.

Bustos Lozano G, Soriano-Ramos M, Pinilla Martín MT, Chumillas Calzada S, García Soria CE, Pallás-Alonso CR. Early hypophosphatemia in high-risk preterm infants: efficacy and safety of sodium Glycerophosphate from first day on parenteral nutrition. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2019;43(3):419–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpen.1426.

Senterre T, Abu Zahirah I, Pieltain C, de Halleux V, Rigo J. Electrolyte and mineral homeostasis after optimizing early macronutrient intakes in VLBW infants on parenteral nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(4):491–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000854.

Mulla S, Stirling S, Cowey S, Close R, Pullan S, Howe R, et al. Severe hypercalcaemia and hypophosphataemia with an optimised preterm parenteral nutrition formulation in two epochs of differing phosphate supplementation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102(5):F451–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-311107.

Christmann V, de Grauw AM, Visser R, Matthijsse RP, van Goudoever JB, van Heijst AF. Early postnatal calcium and phosphorus metabolism in preterm infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(4):398–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000251.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Nutritional needs of the preterm infant. In: Kleinman RE, editor. Pediatric Nutrition. 7th ed. IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2014. p. 86–90.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neonatal parenteral nutrition Ratio of phosphate to amino acids. NICE guideline NG154. 2020. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng154/evidence/d10-ratio-of-phosphate-to-amino-acids-pdf-254996313880.

Nesargi SV, Bhat SR, Rao PNS, Iyengar A. Hypercalcemia in extremely low birth weight neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79(1):124–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-011-0511-0.

Lyon AJ, McIntosh N, Wheeler K, Brooke OG. Hypercalcaemia in extremely low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59(12):1141–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.59.12.1141.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and have equally participated in drafting of the manuscript and/or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient for publication of this Case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Improda, N., Mazzeo, F., Rossi, A. et al. Severe hypercalcemia associated with hypophosphatemia in very premature infants: a case report. Ital J Pediatr 47, 155 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-021-01104-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-021-01104-6