Abstract

Background

Acute otitis media is one of the most common infectious diseases in the paediatric age and although its complications such as acute mastoiditis have become rare thanks to improvements in therapeutic approaches, possible serious complications such as septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint may develop. A prompt diagnosis and adequate treatment are essential to achieving the best outcome and avoiding serious sequelae. We describe a case occurring in a previously healthy 6-year-old female and review the literature currently available on this topic.

Case presentation

The patient presented a right temporomandibular septic arthritis with initial mandibular bone involvement secondary to acute otitis media. She presented with torcicollis, trismus, right preauricular swelling over the temporomandibular joint and was successfully treated with antibiotic treatment alone.

Conclusions

Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint is a rare complication of acute otitis media or acute mastoiditis in children. It should be suspected in patients presenting with trismus, preauricular swelling or fever. No guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease are currently available.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

More than 80% of children under 3 years of age experiences at least one episode of acute otitis media (AOM) and about one third of children has a recurrence by the age of 3 years, making AOM one of the most common paediatric infectious disease [1, 2]. Moreover, in Italy it has been shown that the incidence of AOM in children under 5 years of age in outpatient care is around 16% [3]. One of the most important complications of AOM in the paediatric age is mastoiditis [4].

Other severe complications include subperiosteal abscess, facial paralysis, serous and suppurative labyrinthitis, sigmoid sinus thrombosis, epidural or intracerebral abscess, meningitis, petrous apicitis, and otitic hydrocephalus. Fortunately, modern treatment options make these complications rare in developed countries [5].

Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a rare complication of AOM with or without otomastoiditis in children; however, a prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are crucial to reducing the risk of complications such as TMJ ankylosis and achieving the best outcome [6]. There are currently no guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of TMJ septic arthritis.

Here we report the case of a previously healthy child with right TMJ septic arthritis secondary to AOM. We also review literature reports of otogenic cases of TMJ septic arthritis in children, published in English since 2000, in order to discuss the main clinical findings and the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for this condition.

Case presentation

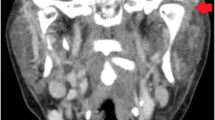

A previously healthy and fully immunised six-year-old girl was admitted to our hospital with right otalgia, progressive trismus and right neck pain for the previous 3 days. She had been on oral antibiotic treatment for right AOM with amoxicillin-clavulanate (80 mg/kg/day) for 2 days without improvement. There was no history of trauma. On admission, the child was in good general conditions and presented with torcicollis, trismus, right preauricular swelling over the temporomandibular joint. On otoscopy right tympanic hyperemia with the evidence of middle ear fluid consistent with AOM was observed. Significant pain on chewing and right-sided cervical lymphadenopathy were also reported. She was apyretic and the rest of her clinical examination was normal. An ultrasound scan revealed a fluid collection of 4 mm in size in the right TMJ. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and neck confirmed the presence of effusion in the right TMJ, consistent with the diagnosis of septic arthritis, with surrounding lymphadenopathy and initial signs of bone rarefaction of the right mandibular condyle. An opacity of the right mastoid was detected radiologically, but there were no clinical signs of mastoiditis. These findings were also confirmed by the subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck (Fig. 1a). On admission, laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 23,420/mm3 with neutrophil predominance and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) of 8.1 mg/dL (normal value < 0.5 mg/dL). A blood culture was also performed but resulted negative. On the basis of these findings, broad spectrum intravenous antibiotic treatment with ceftriaxone (75 mg/kg/day) was introduced, but 3 days later it was replaced with a combination of piperacillin-tazobactam (100 mg/kg/day) and vancomycin (40 mg/kg/day) due to minimal clinical improvement. This antibiotic regimen was well tolerated by the patient and it was continued for a total of 4 weeks with a gradual resolution of the symptoms and normalisation of the white blood cell count and CRP. The patient was discharged in good general conditions under an oral antibiotic treatment with clindamycin (20 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks. The MRI of the head and neck performed 1 month later revealed a further improvement in joint effusion and a reduction in bone involvement (Fig. 1b); ten months after onset a complete resolution was observed on MRI (Fig. 1c).

a STIR coronal image performed in the acute phase shows hyperintensity of the right mandibular condyle consistent with bone oedema/inflammation and minimal effusion in the articular space, suggesting osteoarthritis. b STIR coronal image performed 1 month after discharge shows a reduction in bone hyperintensity and complete reabsorption of the effusion. c STIR coronal image performed 10 months later shows complete recovery of the normal bone intensity of the right mandibular condyle

Discussion and conclusion

Septic arthritis of TMJ is a rare complication of AOM with or without otomastoiditis in children. We identified 34 cases of paediatric TMJ septic arthritis published since 2000 [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Of these, 5 were excluded because the source of the TMJ septic arthritis was not of otogenic origin or was not specified [7, 13, 14]. 8 were case reports, in which 6 cases of TMJ septic arthritis were secondary to AOM, [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Luscan et al. in a prospective study from 2014 to 2015 observed that of 45 patients with acute otomastoiditis, 15 had a TMJ effusion [15]. Finally, in a recent multicentre retrospective study by Burges et al., 9 cases of paediatric TMJ septic arthritis were described. Of these, in 7 cases (78%) the primary middle ear infection was acute mastoiditis, whereas in the two remaining cases the origin of TMJ septic arthritis was AOM [16]. Table 1 summarises the main findings of these reports.

The clinical presentations of TMJ septic arthritis include fever, trismus, preauricular swelling, and TMJ tenderness [13].

In our case, there was no history of fever, but the other main clinical signs were all present.

Although a diagnosis of TMJ septic arthritis can be suspected on the basis of clinical findings, radiological confirmation is essential in order to identify other possible complications. Contrast-enhanced CT is the most frequent imaging technique used in the assessment of TMJ [7, 8, 10,11,12,13]. CT is also easy to perform in children and provides a better distinction between bone and soft tissues [16].

In the case described by Bast et al., MRI was used for diagnosis, whereas Amos et al., in emergent evaluation settings, based their diagnosis on orthopantomography and ultrasound scans [6, 9].

In our case, the ultrasound scan revealed the presence of a fluid collection in the right TMJ, but the CT scan of the head and neck was essential to describing the initial bone involvement. MRI was useful for monitoring the radiological evolution of the condition and preventing our patient from being exposed to radiation.

Laboratory findings often reveal an increase in the white blood cell count and CRP but their specificity and sensitivity are too poor to allow diagnosis without further clinical and radiological data [13]. The most frequent causative organism identified is group A Streptococcus. In one case, it was associated with Staphylococcus epidermidis. In the retrospective study conducted by Burgess et al., of 9 children with TMJ septic arthritis only 3 had an identified causative organism and it was Fusobacterium necrophorum [16]. It is interesting to note that as conventional methods of culturing may not be sensitive enough for the identification of the causative pathogen, Polymerase Chain Reaction was recently described as a useful test for identifying the pathogen [6, 12].

No guidelines on the treatment of TMJ septic arthritis are currently available. Broad spectrum intravenous antibiotic treatment is essential and can be modified on the basis of the antibiograms obtained from the cultural investigations [17]. The duration of the antibiotic treatment is still a matter of debate. In our case, we opted for a 4-week course of intravenous antibiotic followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotic due to initial bone involvement.

Alongside antibiotics, surgery plays a key role in the treatment of septic arthritis in children [18]. Different surgical options are available and these include needle aspiration, aspiration with arthroscopic joint lavage and arthrotomy. However, inadequate evidence is available on what the best surgical treatment option is. Furthermore, surgery should not be considered in patients who respond to ongoing antibiotic treatment, as in our case [17]. Joint aspiration could be useful for decompression, elimination of inflammatory contents, and to facilitate synovial fluid analysis to guide antibiotic therapy, especially in the more severe cases.

Currently, there is no specific data on mandibular physiotherapy; however, different reports have suggested that it could be useful in order to improve condyle excursion and prevent fibrotic adhesions. Active opening and bite exercises in particular could improve maximal incisal opening [13].

To conclude, septic arthritis of the TMJ is a rare but potentially severe complication of AOM or otomastoiditis in children. It should be suspected in the presence of trismus, jaw pain and preauricular swelling, in order to perform radiological examinations to confirm the diagnosis and to initiate adequate antibiotic and, if necessary, surgical treatment. A prompt diagnosis and adequate treatment are essential if severe complications as destruction of the synovial tissues, fibrotic adhesions and joint ankylosis are to be avoided [9].

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing was not applicable to this case report because no datasets were generated or analysed during the study.

Abbreviations

- AOM:

-

Acute otitis media

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

References

Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Zielhuis GA, Rosenfeld RM. Otitis media. Lancet. 2004;363(9407):465–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15495-0.

Pelton SI. Otitis media: re-evaluation of diagnosis and treatment in the era of antimicrobial resistance, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, and evolving morbidity. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2005;52(3):711–28, v-vi. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2005.02.013.

Marchisio P, Cantarutti L, Sturkenboom M, Girotto S, Picelli G, Dona D, Scamarcia A, Villa M, Giaquinto C. Pedianet. Burden of acute otitis media in primary care pediatrics in Italy: a secondary data analysis from the Pedianet database. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:185. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-12-185.

Schilder AG, Marom T, Bhutta MF, Casselbrant ML, Coates H, Gisselsson-Solén M, Hall AJ, Marchisio P, Ruohola A, Venekamp RP, Mandel EM. Panel 7: otitis media: treatment and complications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(4_suppl):S88–S105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599816633697.

Mattos JL, Colman KL, Casselbrant ML, Chi DH. Intratemporal and intracranial complications of acute otitis media in a pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(12):2161–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.09.032.

Bast F, Collier S, Chadha P, Collier J. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint as a complication of acute otitis media in a child: a rare case and the importance of real-time PCR for diagnosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(11):1942–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.08.014.

Viraraghavan R, Kelly L, Podstreleny S, Obeid G. Fever and jaw pain in a five-year-old. TMJ septic arthritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(11):1113, 1115–6.

Hadlock TA, Ferraro NF, Rahbar R. Acute mastoiditis with temporomandibular joint effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(1):111–2. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhn.2001.115664.

Amos MJ, Patterson AR, Worrall SF. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in a 6-year-old child. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(3):242–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.04.019.

Gayle EA, Young SM, McKenna SJ, McNaughton CD. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: case reports and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):674–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.01.034.

Tsai C, Deramo J, Shen X, Vandiver K, Mittal V. Luc's abscess and temporomandibular joint septic arthritis: two rare sequelae of acute otitis media. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001348.

Dubron K, Meeus J, Grisar K, Desmet S, Dormaar T, Spaey Y, Politis C. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint after acute otitis media in a child. Quintessence Int. 2017;48(10):809–13. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a39032.

Frojo G, Tadisina KK, Shetty V, Lin AY. Temporomandibular joint septic arthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(1):e1648. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000001648.

Cai XY, Yang C, Zhang ZY, Qiu WL, Chen MJ, Zhang SY. Septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint: a retrospective review of 40 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(4):731–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.060.

Luscan R, Belhous K, Simon F, Boddaert N, Couloigner V, Picard A, Kadlub N. TMJ arthritis is a frequent complication of otomastoiditis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44(12):1984–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2016.09.015.

Burgess A, Celerier C, Breton S, Van den Abbeele T, Kadlub N, Leboulanger N, Garabedian N, Couloigner V. Otogenic temporomandibular arthritis in children. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(5):466–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2016.3977.

Castellazzi L, Mantero M, Esposito S. Update on the Management of Pediatric Acute Osteomyelitis and Septic Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060855.

Pääkkönen M, Peltola H. Simplifying the treatment of acute bacterial bone and joint infections in children. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2011;9:1125–231. https://doi.org/10.1586/eri.11.140.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This case report was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2019 850/01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MLC, LS and SB wrote the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to patient management. GDP and RP contributed to patient management and to the literature review. IC contributed to the literature review. IB performed the radiological studies. ST and AR contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. PM critically revised the manuscript and supervised patient management. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participation

Not applicable, as it is a case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for the publication of this case report was obtained from the patient’s parents. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Castellazzi, M.L., Senatore, L., Di Pietro, G. et al. Otogenic temporomandibular septic arthritis in a child: a case report and a review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr 45, 88 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0682-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0682-2