Abstract

Background

Patients with isolated traumatic brain injury (TBI) are likely to benefit from effective prehospital care to prevent secondary brain injury. Only a few studies have focused on the impact of advanced interventions in TBI patients by prehospital physicians. The primary end-point of this study was to assess the possible effect of an on-scene anaesthetist on mortality of TBI patients. A secondary end-point was the neurological outcome of these patients.

Methods

Patients with severe TBI (defined as a head injury resulting in a Glasgow Coma Score of ≤8) from 2005 to 2010 and 2012–2015 in two study locations were determined. Isolated TBI patients transported directly from the accident scene to the university hospital were included. A modified six-month Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS) was defined as death, unfavourable outcome (GOS 2–3) and favourable outcome (GOS 4–5) and used to assess the neurological outcomes. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to predict mortality and good neurological outcome. The following prognostic variables for TBI were available in the prehospital setting: age, on-scene GCS, hypoxia and hypotension. As per the hypothesis that treatment provided by an on-scene anaesthetist would be beneficial to TBI outcomes, physician was added as a potential predictive factor with regard to the prognosis.

Results

The mortality data for 651 patients and neurological outcome data for 634 patients were available for primary and secondary analysis. In the primary analysis higher age (OR 1.06 CI 1.05–1.07), lower on-scene GCS (OR 0.85 CI 0.79–0.92) and the unavailability of an on-scene anaesthetist (OR 1.89 CI 1.20–2.94) were associated with higher mortality together with hypotension (OR 3.92 CI 1.08–14.23). In the secondary analysis lower age (OR 0.95 CI 0.94–0.96), a higher on-scene GCS (OR 1.21 CI 1.20–1.30) and the presence of an on-scene anaesthetist (OR 1.75 CI 1.09–2.80) were demonstrated to be associated with good patient outcomes while hypotension (OR 0.19 CI 0.04–0.82) was associated with poor outcome.

Conclusion

Prehospital on-scene anaesthetist treating severe TBI patients is associated with lower mortality and better neurological outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The incidence of patients admitted to hospital with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in Europe is estimated to be 262/100,000, with average related mortality of 11/100,000 [1]. Approximately 10–20% of all TBIs are moderate or severe, requiring intensive care unit treatment [2, 3]. Severe traumatic brain injury is defined as a head injury resulting in a Glasgow Coma Score of ≤8 [4] and the prognosis for severe TBI is that one in two patients dies as a result or is severely affected as a result of the trauma [5, 6]. In large registry studies, TBI outcomes have been demonstrated to be strongly associated with demographic and trauma-related factors (i.e., age, motor score, pupillary reactivity and computed tomography classification) as well as with secondary factors (hypoxia and arterial hypotension primarily) in large registry studies [6,7,8].

Prehospital assessment and treatment is an important link in providing appropriate care [9] as the prognosis of patients with severe TBI strongly depends on early support of vital functions [10, 11]. In particular, prehospital prevention of hypotension and hypoxia by adequate treatment including a secured airway, normoventilation and prevention of aspiration is strongly associated with improved outcome [12,13,14,15].

The effect of advanced interventions by prehospital physicians on patient outcomes has been examined in only a few controlled studies. Increased survival has been found in patients with major trauma and in cardiac arrest patients [16]. In particular, patients with isolated TBI are also likely to benefit from a prehospital physician treating and preventing secondary brain injury insults [17]. Severe TBI patients treated by on-scene anaesthetists have been shown to have a better prognosis in our previous studies [18, 19]. Thus, the current study objective was to further analyse the previously gathered patient data using binary logistic regression analysis. The hypothesis was that interventions by prehospital anaesthetists would have a positive effect on severe TBI patient outcomes. The primary end-point was to evaluate the possible effect of an on-scene anaesthetist on mortality and as a secondary end-point, the neurological outcome in TBI patients.

Methods

Study setting

The prehospital treatment and outcomes of patients with severe TBI from 2005 to 2010 and 2012–2015 in two study locations (Helsinki and Uusimaa region and Pirkanmaa region, Finland) were determined in this retrospective cohort study. The Helsinki and Uusimaa area represents a 10-year continuous patient flow in a physician-staffed emergency medical service (EMS) system. The Pirkanmaa patient cohort was divided into two sections: 2005–2010 with no prehospital physician service and 2011–2015 after the implementation of a physician-staffed EMS unit. Previously gathered patient data, in conjunction with previously unused data (representing 18% of the total information), was further analysed using binary logistic regression analysis. The data covering 2011 were excluded as a physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS) was implemented in the Pirkanmaa Hospital District that year and impacted significantly on the local EMS. There were no dedicated medical directors in the Pirkanmaa area until 2010 and EMS crews consulted on-call hospital physicians for treatment guidelines.

The two present EMS systems, described in detail in previous publications [18, 19], serve a total of almost two million inhabitants and comprise basic life support, advanced life support and physician-staffed units. The physician-staffed units respond to medical emergencies as well as trauma calls. The prehospital physicians are anaesthesiologists with extensive experience in prehospital emergency medicine. All severe TBI patients in these regions are admitted to the region’s single university hospital and receive immediate neurosurgical care according to the national guidelines [20].

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of the Pirkanmaa Hospital District (No. R15158). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the research directors of Tampere University Hospital and Helsinki University Hospital. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT02659046) (originally on 15 January 2016 and then updated on 12 December 2017).

Definitions and data collection

Severe TBI was defined as a GCS score ≤ 8, occurring either on scene, during transportation or verified by an on-call neurosurgeon on admission to hospital [21]. Advanced airway management was defined as securing the airway with endotracheal intubation, a supraglottic airway device (laryngeal mask) or surgical airway. Hypoxia was defined as a SpO2 of ≤90% and hypotension as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≤90 mmHg. The definitions are consistent with the latest edition of the Brain Trauma Foundation’s guidelines for the prehospital management of TBI [4].

Included patients were identified from the hospital records based on ICD-10 discharge diagnoses for TBI (S06.2-S06.6 and S06.8). The inclusion criterion for the study was severe, isolated TBI in patients transported directly from the accident scene to the university hospital. Non-Finnish citizens were excluded from the study since follow-up data were not available to perform a neurological outcome evaluation. Patients with multiple injuries and requiring surgical intervention (other than neurosurgery) were also excluded, as were those who were transferred from other hospitals (i.e., inter-hospital transfers).

Age, gender, response time, total prehospital time, mechanism of injury, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, advanced airway management and vital signs on scene and on arrival at the emergency department (ED) were reviewed and cross-referenced with EMS run sheets and ED documentation.

Mortality data were obtained from the national statistical authority, Statistics Finland. A neurological outcome evaluation was performed based on the hospital patient records up to 6 months after the incident. A modified six-month Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS) [22, 23] was used to assess the neurological outcomes. A GOS of 1 denoted death within 6 months, a GOS of 2–3 was indicative of a poor neurological outcome (i.e., needing assistance with daily living activities) and a GOS of 4–5 was suggestive of good neurological recovery (i.e., the ability to lead an independent life). If the outcome was unclear, the research team members reviewed the case and a joint decision was made.

Statistical methods

To describe general characteristics categorical variables are reported as percentage (%), while continuous variables are reported as median and range. Binary logistic regression analysis was used in univariate and multivariable models to predict mortality and a good neurological outcome. The evaluation was performed in the context of a prehospital environment using predictors that were of value in the prehospital treatment phase [17]. The following known conventional prognostic variables [5, 6] for TBI were available in the prehospital setting: age, on-scene GCS, hypoxia and hypotension. As per the hypothesis that treatment provided by an on-scene anaesthetist would be beneficial to TBI outcomes, physician was added as a potential predictive factor with regard to the prognosis. The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was considered to be a p-value of ≤0.050. The data were analysed using SPSS Statistics for Windows® version 21.0.

Results

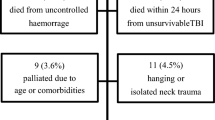

Six hundred and sixty-three patients met the inclusion criterion. The mortality data for 651 patients and neurological outcome data for 634 patients were available for analysis (Fig. 1). Information on the sociodemographic patient characteristics, mechanism of injury, response and total prehospital times is provided in Table 1.

The median on-scene GCS was 5 (≤ 8 in 90%, 9–13 in 8% and 14–15 in 2% of the patients). Patients in the latter two groups deteriorated either on scene or during transportation and were consequently eligible for inclusion. Hypoxia was present on scene in 16% of the patients and hypotension was documented in 3% of them. The incidence of hypoxia (4%) and hypotension (4%) was similar on arrival at the ED. An anaesthetist was present on scene in 72% of the cases and advanced airway management was performed in 74% of the patients. The airway of 97% of the patients was secured in the prehospital setting when an on-scene anaesthetist was present and in 16% of the patients who were not treated by a physician.

Higher age, lower on-scene GCS and the unavailability of an on-scene anaesthetist were associated with higher mortality in univariate analysis. The same variables (age, GCS, an on-scene anaesthetist), together with hypotension, were found to be significant factors for mortality in multivariable analysis (Table 2).

Lower age, a higher on-scene GCS and the presence of an on-scene anaesthetist were linked to good neurological outcomes in univariate analysis. Following multivariable analysis, all of these factors were demonstrated to be significantly associated with good patient outcomes (age, GCS, an on-scene anaesthetist), while hypotension was associated with poor outcomes (Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective observational study, prehospital on-scene anaesthetist treating severe TBI patients was associated with lower mortality and better neurological outcome.

The results supports our previous finding following an evaluation of mortality and neurological outcomes in TBI patients [18, 19]. However, there is lack of consensus on the impact of physician-staffed EMS on trauma patients in the literature and results from existing studies are inconclusive [16, 17, 24,25,26,27].

Early definitive airway control has become an established principle in the management and resuscitation of critically injured patients. This practise is considered to be the standard of care, particularly in patients with head trauma as hypoxemia and hypercapnia can worsen brain injury [28].

Prehospital treatment (i.e., ensuring a secured airway, preventing hypoxemia and enabling controlled ventilation) administered by an on-scene anaesthetist was associated with the observed lower mortality and improved neurological outcome in patients in the current study.

Virtually all patients with severe TBI who were treated by an on-scene anaesthetist had their airways secured in the prehospital setting. This concurs with the finding of a recent study by Gellerfors et al., in which it was shown that prehospital tracheal intubation was completed rapidly, with high success rates and a low incidence of complications when performed by experienced anaesthetists [29].

It has been suggested that the dispatch of physician-staffed EMS could increase on-scene time (OST). It is likely that different prehospital treatment strategies (i.e., “scoop and run” and “stay and play”) and interventions (i.e., airway management performed on scene) influence the OST and, depending on the injury profile, impact on patient outcomes. The literature is also inconclusive regarding the effect of prehospital timeframes on the outcomes of patients with severe TBI [17, 24, 30]. Unfortunately, reliable prehospital OST data were not available in our study.

Hypotension has been shown to have a negative impact on TBI outcomes in previous studies [10, 12]. It has been suggested that SBP values higher than 90 mmHg may benefit patients with isolated, severe TBI [31,32,33,34,35]. Hypotension, or the lack of it, was seen to have a significantly negative impact on survival (i.e., increased mortality) and a significantly positive impact on neurological outcomes, respectively, on multivariable analysis in the current study.

When considering other individual prognostic factors, age is an important predictor of outcome after brain trauma. The elderly (typically defined as age higher than 64–70 years) have higher mortality and worse functional outcomes compared to younger patients with the oldest patients having the poorest outcomes [36,37,38,39]. A GCS score of 3 at presentation is associated with very poor outcomes. Similarly, an increase in mortality and the worsening of neurological outcomes has been demonstrated in patients with a GCS of ≤8 [40,41,42]. A prehospital assessment of the GCS has been found to be an important and reliable indicator of the severity of TBI and should ideally be measured prior to the administration of sedative or paralytic agents [4]. The assessment should be repeatedly conducted to determine improvement or deterioration over time [4]. The results of the current study are comparable with these earlier findings.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study were that this was a population-based study and that all primary EMS mission patients with severe TBI were treated and cared for in the study university hospitals. The included patients were recruited based on a confirmed diagnosis of severe TBI on discharge. Lastly, the mortality data were obtained from the national statistical authority, Statistics Finland, which publishes official causes of death statistics.

A major limitation of this study is that, due to the design, the improved patient outcome can only be associated with the treatment provided by prehospital physician. To obtain prehospital data and timeframes, the study only included patients from primary EMS missions. Also, neurosurgical and intensive care advances were made as well as a new HEMS unit was implemented to one of the EMS system during the study period, all which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. The prehospital data were not originally documented for the purpose of this study, could not be independently verified and thus could have been biased. Continuous data on patient vital signs for the entire prehospital phase were unavailable. Accordingly, transient hypoxia or hypotension during the prehospital period could not be excluded with absolute certainty. Similarly, an eye assessment (pupils) was not recorded for all of the patients. Thus, all of the prognostic variables used in previous studies were not available for analysis in this study. It is possible that the deaths that occurred in the late stages of the follow-up period were unrelated to the prehospital index event, i.e., secondary disease or injury was the cause. The outcome evaluation was based on an evaluation of the patient records by without the ability to perform a clinical examination or with the help of a questionnaire.

Conclusion

Prehospital on-scene anaesthetist treating severe TBI patients is associated with lower mortality and better neurological outcome.

Abbreviations

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- EMS:

-

Emergency medical services

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- GOS:

-

Glasgow Outcome Score

- HEMS:

-

Helicopter emergency medical service

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

References

Peeters W, van den Brande R, Polinder S, Brazinova A, Steyerberg EW, Lingsma HF, Maas AI. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in Europe. Acta Neurochir. 2015;157:1683–96.

Tagliaferri F, Compagnone C, Korsic M, Servadei F, Kraus J. A systematic review of brain injury epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochir. 2006;148:255–68 discussion 68.

Coronado VG, McGuire LC, Sarmiento K, Bell J, Lionbarger MR, Jones CD, Geller AI, Khoury N, Xu L. Trends in traumatic brain injury in the U.S. and the public health response: 1995-2009. J Saf Res. 2012;43:299–307.

Badjatia N, Carney N, Crocco TJ, Fallat ME, Hennes HM, Jagoda AS, Jernigan S, Letarte PB, Lerner EB, Moriarty TM, Pons PT, Sasser S, Scalea T, Schleien CL, Wright DW, Brain Trauma F, Management BTFCfG. Guidelines for prehospital management of traumatic brain injury 2nd edition. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(Suppl 1):S1–52.

Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHugh GS, Murray GD, Marmarou A, Roberts I, Habbema JD, Maas AI. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e165 discussion e65.

Collaborators MCT, Perel P, Arango M, Clayton T, Edwards P, Komolafe E, Poccock S, Roberts I, Shakur H, Steyerberg E, Yutthakasemsunt S. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336:425–9.

Murray GD, Butcher I, McHugh GS, Lu J, Mushkudiani NA, Maas AI, Marmarou A, Steyerberg EW. Multivariable prognostic analysis in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:329–37.

Chi JH, Knudson MM, Vassar MJ, McCarthy MC, Shapiro MB, Mallet S, Holcroft JJ, Moncrief H, Noble J, Wisner D, Kaups KL, Bennick LD, Manley GT. Prehospital hypoxia affects outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury: a prospective multicenter study. J Trauma. 2006;61:1134–41.

Baxt WG, Moody P. The impact of advanced prehospital emergency care on the mortality of severely brain-injured patients. J Trauma. 1987;27:365–9.

Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, Blunt BA, Baldwin N, Eisenberg HM, Jane JA, Marmarou A, Foulkes MA. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma. 1993;34:216–22.

Stocchetti N, Furlan A, Volta F. Hypoxemia and arterial hypotension at the accident scene in head injury. J Trauma. 1996;40:764–7.

Wang HE, Peitzman AB, Cassidy LD, Adelson PD, Yealy DM. Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation and outcome after traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:439–50.

Murray JA, Demetriades D, Berne TV, Stratton SJ, Cryer HG, Bongard F, Fleming A, Gaspard D. Prehospital intubation in patients with severe head injury. J Trauma. 2000;49:1065–70.

Davis DP. Prehospital intubation of brain-injured patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:142–8.

Davis DP. Early ventilation in traumatic brain injury. Resuscitation. 2008;76:333–40.

Botker MT, Bakke SA, Christensen EF. A systematic review of controlled studies: do physicians increase survival with prehospital treatment? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:12.

Franschman G, Verburg N, Brens-Heldens V, Andriessen TM, Van der Naalt J, Peerdeman SM, Valk JP, Hoogerwerf N, Greuters S, Schober P, Vos PE, Christiaans HM, Boer C. Effects of physician-based emergency medical service dispatch in severe traumatic brain injury on prehospital run time. Injury. 2012;43:1838–42.

Pakkanen T, Virkkunen I, Kamarainen A, Huhtala H, Silfvast T, Virta J, Randell T, Yli-Hankala A. Pre-hospital severe traumatic brain injury - comparison of outcome in paramedic versus physician staffed emergency medical services. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:62.

Pakkanen T, Kamarainen A, Huhtala H, Silfvast T, Nurmi J, Virkkunen I, Yli-Hankala A. Physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical service has a beneficial impact on the incidence of prehospital hypoxia and secured airways on patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25:94.

Traumatic Brain Injury (online). Current Care Guidelines.Working group set up by the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Helsinki: The Finnish Medical Society Duodecim; 2017. [www document]. http://www.kaypahoito.fi/web/english/home. Accessed 21 May 2018].

Marshall LF, Becker DP, Bowers SA, Cayard C, Eisenberg H, Gross CR, Grossman RG, Jane JA, Kunitz SC, Rimel R, Tabaddor K, Warren J. The National Traumatic Coma Data Bank. Part 1: design, purpose, goals, and results. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:276–84.

Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–4.

Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–4.

de Jongh MA, van Stel HF, Schrijvers AJ, Leenen LP, Verhofstad MH. The effect of helicopter emergency medical services on trauma patient mortality in the Netherlands. Injury. 2012;43:1362–7.

Ringburg AN, Thomas SH, Steyerberg EW, van Lieshout EM, Patka P, Schipper IB. Lives saved by helicopter emergency medical services: an overview of literature. Air Med J. 2009;28:298–302.

Frankema SP, Ringburg AN, Steyerberg EW, Edwards MJ, Schipper IB, van Vugt AB. Beneficial effect of helicopter emergency medical services on survival of severely injured patients. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1520–6.

Garner AA, Mann KP, Fearnside M, Poynter E, Gebski V. The Head Injury Retrieval Trial (HIRT): a single-centre randomised controlled trial of physician prehospital management of severe blunt head injury compared with management by paramedics only. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:869–75.

Carney N, Totten AM, O’Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GW, Bell MJ, Bratton SL, Chesnut R, Harris OA, Kissoon N, Rubiano AM, Shutter L, Tasker RC, Vavilala MS, Wilberger J, Wright DW, Ghajar J. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery. 2016;80(1):6–15. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000001432.

Gellerfors M, Fevang E, Backman A, Kruger A, Mikkelsen S, Nurmi J, Rognas L, Sandstrom E, Skallsjo G, Svensen C, Gryth D, Lossius HM. Pre-hospital advanced airway management by anaesthetist and nurse anaesthetist critical care teams: a prospective observational study of 2028 pre-hospital tracheal intubations. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1103–9.

Ringburg AN, Spanjersberg WR, Frankema SP, Steyerberg EW, Patka P, Schipper IB. Helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS): impact on on-scene times. J Trauma. 2007;63:258–62.

Spaite DW, Hu C, Bobrow BJ, Chikani V, Sherrill D, Barnhart B, Gaither JB, Denninghoff KR, Viscusi C, Mullins T, Adelson PD. Mortality and prehospital blood pressure in patients with major traumatic brain injury: implications for the hypotension threshold. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:360–8.

Brenner M, Stein DM, Hu PF, Aarabi B, Sheth K, Scalea TM. Traditional systolic blood pressure targets underestimate hypotension-induced secondary brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1135–9.

Berry C, Ley EJ, Bukur M, Malinoski D, Margulies DR, Mirocha J, Salim A. Redefining hypotension in traumatic brain injury. Injury. 2012;43:1833–7.

Fuller G, Hasler RM, Mealing N, Lawrence T, Woodford M, Juni P, Lecky F. The association between admission systolic blood pressure and mortality in significant traumatic brain injury: a multi-centre cohort study. Injury. 2014;45:612–7.

Butcher I, Maas AI, Lu J, Marmarou A, Murray GD, Mushkudiani NA, McHugh GS, Steyerberg EW. Prognostic value of admission blood pressure in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:294–302.

Mosenthal AC, Lavery RF, Addis M, Kaul S, Ross S, Marburger R, Deitch EA, Livingston DH. Isolated traumatic brain injury: age is an independent predictor of mortality and early outcome. J Trauma. 2002;52:907–11.

Susman M, DiRusso SM, Sullivan T, Risucci D, Nealon P, Cuff S, Haider A, Benzil D. Traumatic brain injury in the elderly: increased mortality and worse functional outcome at discharge despite lower injury severity. J Trauma. 2002;53:219–23 discussion 23-4.

Rakier A, Soustiel JF, Gilburd J, Zaaroor M, Alkalai N, Welblum E, Feinsod M. Head injury in the elderly. Harefuah. 1995;128:474–7 528-7.

Mamelak AN, Pitts LH, Damron S. Predicting survival from head trauma 24 hours after injury: a practical method with therapeutic implications. J Trauma. 1996;41:91–9.

Sadaka F, Jadhav A, Miller M, Saifo A, O’Brien J, Trottier S. Is it possible to recover from traumatic brain injury and a Glasgow coma scale score of 3 at emergency department presentation? Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(9):1624–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.051. Epub 2018 Jan 31.

Tien HC, Cunha JR, Wu SN, Chughtai T, Tremblay LN, Brenneman FD, Rizoli SB. Do trauma patients with a Glasgow coma scale score of 3 and bilateral fixed and dilated pupils have any chance of survival? J Trauma. 2006;60:274–8.

Kotwica Z, Jakubowski JK. Head-injured adult patients with GCS of 3 on admission--who have a chance to survive? Acta Neurochir. 1995;133:56–9.

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author would like to express his gratitude to M.D., PhD Antti Kämäräinen, M.D., PhD Ilkka Virkkunen and professor Arvi Yli-Hankala for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

This study is dedicated to the memory of Janne Virta, M.D.

Funding

This study was supported by a study grant from FinnHEMS ltd, Research and Development Unit.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Declarations

The study was conducted in the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District, Finland and in the Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TP the concept and design of the study, acquisition and evaluation of the data and corresponding author. JN the concept and design of the study, evaluation of the data and the manuscript. HH statistical analyses. TS evaluation of the data and the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District (No. R15158). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the research directors of Tampere University Hospital and Helsinki University Hospital. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT02659046) (originally on 15 January 2016 and then updated on 12 December 2017).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pakkanen, T., Nurmi, J., Huhtala, H. et al. Prehospital on-scene anaesthetist treating severe traumatic brain injury patients is associated with lower mortality and better neurological outcome. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 27, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0590-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0590-x