Abstract

Background

Granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) account for approximately 2% of ovarian malignancies and are considered a rare type of ovarian cancer. GCTs are characterized by irregular genital bleeding after menopause due to female hormone production as well as late recurrence around 5–10 years after initial treatment. In this study, we investigated two cases of GCTs to find a biomarker that can be used to evaluate the treatment and predict recurrence.

Case presentation

Case 1 was a 56-year-old woman who presented to our hospital with abdominal pain and distention. An abdominal tumor was found, and GCTs were diagnosed. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels decreased after surgery. Case 2 involved a 51-year-old woman with refractory GCTs. Carboplatin–paclitaxel combination therapy and bevacizumab were administered after the tumor resection. After chemotherapy, a decline in VEGF levels was observed, but serum VEGF levels increased again with disease progression.

Conclusions

VEGF expression may be of clinical importance in GCTs as a clinical biomarker for disease progression, which may be used to determine the efficacy of bevacizumab against GCTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

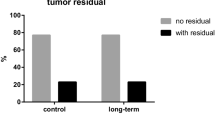

Granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) are rare tumors, representing 2–5% of all ovarian cancers [1]. Due to their rarity, detailed information on their pathogenesis and molecular characteristics is limited [2,3,4]. The standard treatment comprises debulking surgery, including hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy, for all patients with GCTs [1, 3]. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended in patients with advanced stage or stage I disease with high-risk factors, including tumor rupture, advanced age, menopause, and mitotic rate [3, 5]. Recently, a notable survey report on GCTs by Ebina et al. [6] reported the possibility of omitting diagnostic lymph node dissection for patients with pT1 during the initial surgery for pT1 GCTs. For patients with pT2 or higher, systematic dissection is required for the diagnosis of lymph node metastases. Careful observation of the abdominal cavity at the start of surgery is necessary to determine whether total dissection is required, especially in advanced cases with intraperitoneal dissemination, suggesting that achieving zero residual tumors or adequate tumor reduction is associated with improved prognosis. Thus, no residual tumors should be required in the surgical treatment of GCTs to avoid the recurrence. Nevertheless, evidence-based management of aggressive GCTs is limited, and GCTs tend to eventually recur after initial treatment [3]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used for diagnosis, but it has known limitations [7]. Angiogenesis reportedly plays a critical role in the development and progression of GCTs [2, 3], and overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been reported to correlate with shorter disease-specific survival and poorer outcomes [3, 8], which may support the clinical benefits of anti-VEGF therapy [2, 8, 9]. Here, we present two cases of aggressive GCTs in which serum VEGF levels were measured and examined whether serum VEGF levels are predictive of recurrence.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 56-year-old female presented to our hospital with severe abdominal distention, fatigue, nausea, and abdominal pain. She was initially taken to the emergency room. A chest x-ray showed significant pleural effusion in the right lung field, and an abdominal x-ray showed intestinal gas accumulation. She was admitted to the hospital for a thorough examination. She had no medical history or history of allergies. Blood tests performed on admission showed that the patient was severely anemic, with Hb of 5.6; therefore, six red blood cell transfusion units were administered and pleurodesis was performed to remove 1,500 mL of fluid. Cytology of the uterine cervix and endometrium was clear, and transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a substantial pelvic mass. MRI revealed an abdominal mass with a diameter of 30 cm (Fig. 1), ascites, and pleural effusion. Tumor marker levels were as follows: serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125), 776.1 U/mL; CA19-9, 17.9 U/mL; CEA, 2.0 ng/mL; and estradiol, 498.7 pg/mL. Computed tomography (CT) revealed no metastases. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that the preoperative serum VEGF level was 1830 pg/mL. We performed total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy. We found approximately 4,000 mL of yellowish ascites and a left ovarian tumor adhered to the omentum and peritoneum. No abnormal findings were observed in other organs, including the uterus, right ovary, bilateral tubes, and omentum. In addition, no residual disease was observed in the abdomen after the surgery. Grossly, the left ovarian tumor measured 31 cm in diameter and contained a white solid portion with hemorrhage and necrosis (Fig. 2). Pathological findings revealed diffuse proliferation of atypical cells with high N/C ratios, some of which had “coffee bean” nuclei (Fig. 3A), which was pathologically consistent with GCTs. Immunohistochemically, VEGF was highly expressed in the tumor (Fig. 3B). One day after surgery, serum VEGF levels decreased to 750 pg/mL, as determined by ELISA. She was discharged eight days after surgery, and there has been no evidence of recurrence over the 4-year follow-up.

Case 2

The patient was a 51-year-old female. She had undergone laparoscopic right salpingo-oophorectomy in another hospital 19 years prior and had been diagnosed with GCTs. She had undergone tumor resection at our institute for recurrence three times, and subsequently underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with left salpingo-oophorectomy and dissemination resection. Five years after the last surgery, recurrence was noted and tumor resection was performed again. After surgery, carboplatin-paclitaxel combination therapy (CP therapy) was administered. Before the administration of CP therapy, the serum VEGF level was 1680 pg/mL. Increased pleural effusion and ascites were found after the first cycle of CP therapy; therefore, bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against VEGF, was administered in combination with CP therapy. A reduction in ascites and pleural effusion was observed, and CP therapy with bevacizumab was continued. Two months after TC therapy, the serum VEGF level was 107 pg/mL. However, after three cycles of CP therapy, the serum VEGF level was slightly elevated (130.8 pg/mL), and CT revealed tumor dissemination and enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvis. Recurrence was suspected, but as the patient refused additional chemotherapy, palliative therapy was administered. The patient was alive at the 1-year follow-up after administration of CP therapy.

Discussion and conclusions

Surgery is the standard initial treatment for GCTs, and complete tumor resection is recommended for all patients [4]. However, postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy has limited efficacy and novel treatments for GCTs are required. Indeed, although it has been reported that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is unnecessary in FIGO stage IC GCTs [10], Case 2 in this report showed repeated recurrences. It is well known that high VEGF expression is associated with survival of ovarian cancer [11]. In addition, previous studies have reported overexpression of VEGF in GCTs, both primary and recurrent types [9, 12]; thus, it has been associated with tumor angiogenesis and progression of GCTs. We have experienced two cases of GCTs with serum VEGF measurements, and we identified other cases of GTC diagnosed and treated in our institute, from the medical records. We summarized the VEGF immunohistochemistry results for GCTs in Table 1. A VEGF antibody (A-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Tokyo, Japan) was used in the immunohistochemistry staining. The staining patterns of VEGF were almost homogeneous, and most cases were positive for VEGF in over 90% of tumor cells. The cases were divided into three groups with staining intensities of “moderate,” “high,” or “very high,” which was determined by a consensus between two researchers (K.S. and Y.S.). Both cases were positive for VEGF in tumor cells, and there was a tendency for strong staining with large tumors. Moreover, previous studies have reported that serum VEGF levels are elevated in cases of GCTs [9], and that there is no correlation between serum VEGF levels and tumor size or stage. In our study, serum VEGF levels were analyzed in two cases, and serum VEGF levels were almost high. These findings have been noted in previous studies [13, 14], but whether they predict recurrence is not well known. The limitation of this study is that it is a case report. However, the quantitative evaluation of serum VEGF levels over time in patients with advanced granulosa cell tumors, along with simultaneously conducted immunohistological studies may provide a new perspective on future treatment strategies for granulosa cell tumors.

Serum VEGF levels were higher in the primary tumor case than in the recurrent case in our analysis, which was consistent with a previous study [7], possibly due to an increased VEGF-producing tumor burden in the primary tumor case compared with that in the recurrent case.

As shown in our cases, serum VEGF levels decreased after treatment, which comprised surgery and chemotherapy, reflecting tumor cytoreduction and a decrease in ascites. A previous study reported a decrease in serum VEGF levels after tumor removal [15]; however, our case showed decreased serum VEGF levels after adjuvant chemotherapy, and elevated VEGF levels before detecting disease progression, which supports the clinical efficacy of VEGF in cases of GCTs. Therefore, we suggest that serum VEGF levels have clinical significance as a biomarker of residual tumors in GCTs.

Previous studies have reported the efficacy of bevacizumab in GCTs [2, 3, 13, 16, 17]. In addition, it may be useful for controlling neovascularization-related symptoms, such as VEGF-mediated ascites in ovarian cancer [2], as shown in Case 2 in our study. The overall response and clinical benefit rates of bevacizumab in recurrent GCTs are 38% and 63%, respectively [3]. Thus, bevacizumab may be clinically important for controlling disease progression. However, as the insurance coverage for chemotherapy of GCTs is limited, our findings may be helpful for the selection of appropriate chemotherapy agents for aggressive GCTs.

In conclusion, serum VEGF levels may be of clinical importance as a biomarker for GCTs, and bevacizumab may be useful for recurrent GCTs. Further studies are required to evaluate the efficacy of serum VEGF levels and bevacizumab in patients with GCTs.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is owned by Teikyo University hospital but could be made available on request. Personal information will not be provided to ensure anonymity of the patient.

Abbreviations

- GCTs:

-

Granulosa cell tumors

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Schumer ST, Cannistra SA. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1180–9.

Barrena Medel NI, Herzog TJ, Wright JD, Lewin SN. Neoadjuvant bevacizumab in a granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: a case report. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4767–8.

Tao X, Sood AK, Deavers MT, Schmeler KM, Nick AM, Coleman RL, et al. Anti-angiogenesis therapy with bevacizumab for patients with ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:431–6.

Wang WC, Lai YC. Molecular pathogenesis in granulosa cell tumor is not only due to somatic FOXL2 mutation. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:88.

Wang D, Xiang Y, Wu M, Shen K, Yang J, Huang H, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of adult ovarian granulosa cell tumor: a single-institution experience in China. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:1315–22.

Ebina Y, Yamagami W, Kobayashi Y, Tabata T, Kaneuchi M, Nagase S, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors of ovarian granulosa cell tumors: a JSGO-JSOG joint study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:269–73.

Nagawa K, Kishigami T, Yokoyama F, Murakami S, Yasugi T, Takaki Y, et al. Diagnostic utility of a conventional MRI-based analysis and texture analysis for discriminating between ovarian thecoma-fibroma groups and ovarian granulosa cell tumors. J Ovarian Res. 2022;15:65.

Brown J, Deavers MT, Nick AM, Millojevic L, Gershenson DM, Sood AK. Vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression and angiogenesis are prevalent and predict clinical outcome in sex cord-stromal ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112;S95.

Färkkilä A, Anttonen M, Pociuviene J, Leminen A, Butzow R, Heikinheimo M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR-2 are highly expressed in ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:115–22.

Wang D, Xiang Y, Wu M, Shen K, Yang J, Huang H, et al. Is adjuvant chemotherapy beneficial for patients with FIGO stage IC adult granulosa cell tumor of the ovary? J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:25.

Guo BQ, Lu WQ. The prognostic significance of high/positive expression of tissue VEGF in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:30552–60.

Li J, Bao R, Peng S, Zhang C. The molecular mechanism of ovarian granulosa cell tumors. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:13.

Kottarathil VD, Antony MA, Nair IR, Pavithran K. Recent advances in granulosa cell tumor ovary: a review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4:37–47.

Mills AM, Chinn Z, Rauh LA, Dusenbery AC, Whitehair RM, Saks E, et al. Emerging biomarkers in ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:560–5.

Färkkilä A, Pihlajoki M, Tauriala H, Bützow R, Leminen A, Unkila-Kallio L, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF) is elevated in patients with ovarian granulosa cell tumor (GCT), and VEGF inhibition by bevacizumab induces apoptosis in GCT in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1973–81.

Kesterson JP, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Lele S. The use of bevacizumab in refractory ovarian granulosa-cell carcinoma with symptomatic relief of ascites: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:527–9.

Brown J, Brady WE, Schink J, Van Le L, Leitao M, Yamada SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab in recurrent sex cord-stromal ovarian tumors: results of a phase 2 trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer. 2014;120:344–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the critical discussions with our colleagues at Teikyo University.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (K.N.) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT and KN performed literature review and wrote the manuscript. TI, SF, KH, HN, YT, HH, KS, YS, and KN participated in literature review. SF, YM, KS, YS and KN performed pathological diagnosis and prepared images. All authors were involved in the management of the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed under the approval of the ethics committee at Teikyo University (13-003-2) and with written informed consent from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Takasaki, K., Ichinose, T., Miyagawa, Y. et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor associated with the progression of granulosa cell tumor: a report of two cases. J Ovarian Res 16, 112 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-023-01197-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-023-01197-z