Abstract

Background

Fibroblast growth factor 13 (FGF13) is one of the most highly expressed FGF family members in adult mouse ovary. However, its precise roles in ovarian function remain largely unknown. We sought to evaluate the associations between FGF13 in follicular fluid and oocyte developmental competence in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 43 patients with PCOS and 32 non-PCOS patients who underwent in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatments. The highest quartiles of follicular fluid (FF)-FGF13 (≥117.51 pg/mL) and FF-total testosterone (FF-TT) (≥51.90 nmol/L) were defined as “elevated” FF-FGF13 levels and “elevated” FF-TT levels, respectively.

Results

The levels of FF-FGF13 were skewed, with a median of 82.97 pg/mL (59.79–117.51 pg/mL) in 75 patients. The prevalence of elevated FF-TT levels was significantly higher in the PCOS patients with elevated FF-FGF13 levels than in those without (64.3% vs. 35.7%, adjusted P = 0.0096). FF-TT and increased ovarian volume (> 10 mL for one or both ovaries) were positively correlated with FF-FGF13 in PCOS patients (r = 0.37, P = 0.013; r = 0.33, P = 0.032). A negative association was evident between FF-FGF13 and the MII oocyte rate in the multiple linear regression analysis (β = − 0.10, SE = 0.045, adjusted P = 0.027). However, the associations were not evident in the non-PCOS patients.

Conclusions

Our study suggests the presence of intrafollicular FGF13 in PCOS patients and implies that FGF13 might be involved in the pathophysiological process of PCOS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The control of ovarian function is highly complex and often involves multiple endocrine and paracrine signaling factors. In addition to pituitary gonadotrophins, several families of growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factors and transforming growth factors, play crucial roles in ovarian function [1,2,3,4].

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, comprising 18 secreted proteins and four intracellular proteins (FGF11–14), participate in the regulation of ovarian function and follicular development [5, 6]. For example, FGF2 promotes granulosa cell proliferation and affects ovarian steroidogenesis [7, 8]. Furthermore, FGF18 is involved in the apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells [9, 10].

The expression of FGF13 in the murine ovary was reported as early as 1997 [11]. In addition to FGF1 and FGF12, FGF13 is a member of the FGF family that is highly expressed in the adult mouse ovary [12]. FGF13 mRNA is detectable in the corpora lutea, theca and granulosa cells of bovine antral follicles. Moreover, FGF13 mRNA expression is upregulated in the theca cells of the bovine ovary during antral follicle development [13]. Nevertheless, the precise roles of FGF13 in ovarian physiology remain largely unknown.

To our knowledge, the data describing FGF13 expression in the adult human ovary is limited. Therefore, the objectives of our study were to detect the presence of follicular fluid (FF)-FGF13 and to evaluate the relationship between FF-FGF13 and oocyte developmental competence in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI).

Materials and methods

Subjects and study design

A total of 75 patients aged 20–37 years undergoing first IVF/ICSI were recruited consecutively from Aug. 2014 to Aug. 2015 at the Center for Reproductive Medicine, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The patients had no medical history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperprolactinemia, thyroid disease, Cushing’s syndrome, or congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Patients who were using insulin-sensitizing drugs, oral contraceptives, corticosteroids, anti-androgens or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists/antagonists or who had undergone unilateral ovariectomy were excluded. Ultimately, 43 (57.3%) cases of PCOS and 32 (42.7%) cases of tubal infertility were included in the analyses.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital with informed consent.

Collection of follicular fluid and biochemical measurements

Ovarian stimulation was performed using a GnRH antagonist protocol, and hCG (Lvzhu) was administered to trigger ovulation after adequate follicle development, as described previously [14]. Oocyte retrieval and follicular-fluid samples without blood contamination were collected under local anesthesia using vaginal ultrasound-guided punctures of follicles 36 h after hCG administration. Standard procedures were carried out for gamete-embryo handling, and embryo transfer was performed under abdominal ultrasonography guidance. The ICSI procedure was performed 4–6 h after oocyte retrieval.

Approximately 16–18 h after ICSI, the assessment of fertilization was performed. All embryos were scored as follows: Grade I, embryos with ≤5% fragmentation; Grade II, embryos with ≤20% fragmentation; Grade III, embryos with ≤50% fragmentation; and Grade IV, embryos with > 50% fragmentation [15]. On day 3, Grade I/II embryos were classified as high-quality embryos.

The levels of total testosterone (TT), estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in the follicular fluid were measured with chemiluminescence immunoassays (Elecsys autoanalyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and the free androgen index (FAI) was calculated with the following formula: FAI = 100 × TT/SHBG (nmol/L). The levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), FGF13 and FGF21 in the follicular fluid were measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (CUSABIO Biotech Co., Ltd., Newark, DE, USA). The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were < 10%.

Diagnosis and definition

Polycystic ovaries were defined as follows: the presence of 12 or more follicles in each ovary measuring 2–9 mm in diameter and/or increased ovarian volume (> 10 mL for one or both ovaries) by transvaginal ultrasound. PCOS was defined when at least two of the following three criteria were met: oligo-ovulation or anovulation; clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism; and polycystic ovaries according to the revised Rotterdam consensus [16]. Thirty-two patients with tubal infertility who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for PCOS and had no family history of PCOS were defined as non-PCOS patients.

In the present study, “elevated” FF-FGF13 levels were defined as follicular levels in the upper quartile (i.e., ≥117.51 pg/mL). “Elevated” FF-TT levels were defined as follicular levels in the upper quartile (i.e., ≥51.90 nmol/L).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables due to skewed distributions are shown as medians (interquartile range). Categorical variables are shown as absolute numbers (percentages).

The baseline characteristics of the patients with and without elevated FF-FGF13 levels were described and compared using the Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Spearman correlations were performed to evaluate the relationships of FF-FGF13 to age, BMI, increased ovarian volume, FF-LH, FF-FSH, FF-TT, FF-FAI, FF-E2, FF-P4, FF-IL-6, and FF-FGF21 in the PCOS and non-PCOS patients. Spearman correlations and multiple linear regression analyses adjusted for age, BMI, FF-LH, and FF-FSH were performed to evaluate the associations between FF-FGF13 and oocyte developmental competence in the PCOS and non-PCOS patients.

Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of the study patients

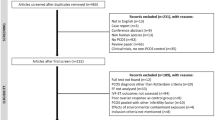

A total 75 patients with a mean age of 27.7 ± 3.7 years were enrolled. The distribution of the FF-FGF13 levels was skewed with a median of 82.97 pg/mL (interquartile range 59.77–117.51 pg/mL). Figure 1 presents the histogram of the FF-FGF13 levels.

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the patients with and without elevated FF-FGF13 levels. The patients with elevated FF-FGF13 levels had higher levels of FF-TT, FF-FAI, and FF-FGF21 than those without elevated FF-FGF13 levels (all P values < 0.05). The prevalence of increased ovarian volume was significantly higher among patients with elevated FF-FGF13 levels than among those without elevated FF-FGF13 levels (68.2% vs. 38.9%, P = 0.021). No significant differences were evident in terms of age, BMI, FF-LH, FF-FSH, FF-E2, FF-P4, or FF-IL6 between the patients with and without elevated FF-FGF13 levels.

The prevalence of elevated FF-TT levels was significantly higher among PCOS patients with elevated FF-FGF13 levels than among those without elevated FF-FGF13 levels (64.3% vs. 35.7%, fully adjusted P = 0.0096). The prevalence of increased ovarian volume appeared to be higher among PCOS patients with elevated FF-FGF13 levels than among those without elevated FF-FGF13 levels (57.1% vs. 42.7%); however, the P value did not show a significant difference (Fig. 2).

Prevalence of elevated FF-TT levels and increased ovarian volume in PCOS patients with and without elevated FF-FGF13 levels. Panel a: Prevalence of elevated FF-TT levels in PCOS patients with and without elevated FF-FGF13 levels. Panel b: Prevalence of increased ovarian volume in PCOS patients with and without elevated FF-FGF13 levels. P values were accessed using multiple logistic regression models adjusted for age, BMI, FF-FSH, and FF-LH

Factors associated with FF-FGF13 in patients with and without PCOS

As shown in Table 2, FF-TT and increased ovarian volume were positively correlated with FF-FGF13 in PCOS patients (r = 0.37, P = 0.013 and r = 0.33, P = 0.032). However, no significant relationships were evident between FF-FGF13 and FF-TT or increased ovarian volume among the non-PCOS patients (both P values > 0.05).

Associations between FF-FGF13 and oocyte developmental competence in patients with and without PCOS

As shown in Table 3, Spearman correlations revealed that FF-FGF13 was significantly correlated with the MII oocyte rate in the PCOS patients (r = − 0.42, P = 0.0055). The negative association persisted after the adjustments for age, BMI, FF-LH and FF-FSH in the multiple linear regression analysis (β = − 0.10, SE = 0.045 and P = 0.027). FF-FGF13 was significantly correlated with the fertilization rate in the non-PCOS patients (r = 0.52, P = 0.0037). However, the association disappeared in the multiple linear regression analysis (β = 0.078, SE = 0.099 and P = 0.44).

No associations were evident between FF-FGF21 and oocyte developmental competence for the PCOS patients when Spearman correlations were used (see Additional file 1).

Discussion

This study is the first to report the presence of FGF13 in the follicular fluid of women undergoing IVF/ICSI. Moreover, FF-FGF13 was significantly associated with FF-TT and the MII oocyte rate in PCOS patients undergoing first IVF/ICSI in China.

Although FGF13 has been detected in the ovaries of rodents and cows, its expression in the ovaries of other species has remained unknown. FGF13 expression was first reported in the murine ovary by Helge Hartung [11]. Thereafter, FGF13 mRNA was observed in bovine theca and granulosa cells [17]. Afterward, the above results were confirmed by I.B. Costa et al. [13]. In the present study, FGF13 was detected in the follicular fluid of women undergoing first IVF/ICSI, which has direct implications for the roles of FGF13 in human ovarian function.

Despite similarities with other secreted FGFs, FGF13 has not been regarded as a secreted protein due to its lack of N-terminal signal sequences. However, our study demonstrated the presence of FGF13 in the follicular fluid of women undergoing IVF/ICSI. Moreover, the concentrations of FF-FGF13 were much higher than the levels of IL-6 in the follicular fluid, which is one of the endocrine factors. The results raise the possibility that FGF13 might be transported to the extracellular space. If so, the secretory mechanism of FGF13 might function in the same manner as that of FGF1 [18], despite the absence of a signal peptide. All of these possibilities require further investigation.

In the present study, FGF13 was associated with FF-TT in PCOS patients, raising the possibility of its essential role in the pathophysiological process of PCOS. Being different from other FGF family members, FGF13 cannot interact with FGF receptor tyrosine kinases [19]. The major downstream signaling pathways in the ovary function responsible for the association remain to be clarified. In previous research, FGF13 inhibited C2C12 cell differentiation by activating the extracellular signal-regulated kinases/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) pathway [20]. FGF13 was associated with the differential expression of the MAPK pathway in Sotos syndrome [21]. On the other hand, the MAPK pathway participated in the control of ovarian testosterone production [22]. Thus, we hypothesized that MAPK singling pathways were involved in the association between FGF13 and the testosterone secretion of the human ovary.

In addition to hyperandrogenism, the formation of ovarian interstitial fibrosis is a major cause of reproductive dysfunction in PCOS. In addition to MAPK singling pathways, the P38MAPK pathway, which is downstream of the FGF13 signaling pathway [23, 24], is involved in the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2 and MMP9, which play important roles in extracellular matrix degradation in PCOS. Thus, FGF13 may be involved in ovarian interstitial fibrosis.

FGF21, a member of the family of secreted FGFs, is associated with insulin resistance [25, 26], an important aspect of the pathogenesis of PCOS. To explore its roles in PCOS, the levels of FGF21 in follicular fluid were examined in our study. The results showed that FGF21 was present in follicular fluid, but that it was not associated with oocyte developmental competence in PCOS patients undergoing IVF, implying that FGF21 in the follicular microenvironment might not be involved in oocyte developmental competence in PCOS patients.

The limitations of our study should be mentioned. First, the concentrations of FGF13 were examined in infertile patients after superovulation and not under normal physiological conditions. Second, the relatively small number of patients may have influenced the statistical power, and thus, a large-scale population study is needed in the future. Third, although possible covariates were included in the adjustments, some residual or undetected confounding factors could not be ruled out.

In summary, the present study reported the presence of FGF13 in the follicular fluid of women undergoing IVF/ICSI. Moreover, the relationships between FF-FGF13 and FF-TT, ovarian morphology and oocyte developmental competence imply that FF-FGF13 might be involved in the pathophysiological process of PCOS. FGF13 might be a promising intervention target in PCOS, as long as the potential mechanisms are clarified.

References

Law NC, Hunzicker-Dunn ME. Insulin Receptor Substrate 1, the Hub Linking Follicle-stimulating Hormone to Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Activation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:4547–60.

Mendes CC, Mirth CK. Stage-Specific Plasticity in Ovary Size Is Regulated by Insulin/Insulin-Like Growth Factor and Ecdysone Signaling in Drosophila. Genetics. 2016;202:703–19.

Mottershead DG, Sugimura S, Al-Musawi SL, Li JJ, Richani D, White MA, et al. Cumulin, an Oocyte-secreted Heterodimer of the Transforming Growth Factor-β Family, Is a Potent Activator of Granulosa Cells and Improves Oocyte Quality. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:24007–20.

Chen YC, Chang HM, Cheng JC, Tsai HD, Wu CH, Leung PC. Transforming growth factor-β1 up-regulates connexin43 expression in human granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2190–201.

Parrott JA, Vigne JL, Chu BZ, Skinner MK. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in the ovarian follicle involve keratinocyte and hepatocyte growth factor production by thecal cells and their action on granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1994;135:569–75.

Buratini J Jr, Pinto MG, Castilho AC, Amorim RL, Giometti IC, Portela VM, et al. Expression and function of fibroblast growth factor 10 and its receptor, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2B, in bovine follicles. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:743–50.

Lavranos TC, Rodgers HF, Bertoncello I, Rodgers RJ. Anchorage-independent culture of bovine granulosa cells: the effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and dibutyryl cAMP on cell division and differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:245–51.

Vernon RK, Spicer LJ. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and heparin on follicle stimulating hormone-induced steroidogenesis by bovine granulosa cells. J Anim Sci. 1994;72:2696–702.

Jiang Z, Guerrero-Netro HM, Juengel JL, Price CA. Divergence of intracellular signaling pathways and early response genes of two closely related fibroblast growth factors, FGF8 and FGF18, in bovine ovarian granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;375:97–105.

Portela VM, Machado M, Buratini J Jr, Zamberlam G, Amorim RL, Goncalves P, et al. Expression and function of fibroblast growth factor 18 in the ovarian follicle in cattle. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:339–46.

Hartung H, Feldman B, Lovec H, Coulier F, Birnbaum D, Goldfarb M. Murine FGF-12 and FGF-13: expression in embryonic nervous system, connective tissue and heart. Mech Dev. 1997;64:31–9.

Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Ding X, Kurosu H, John GB, Wang L, et al. Research resource: comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(10):2050–64.

Costa IB, Teixeira NA, Ripamonte P, Guerra DM, Price C, Buratini J Jr. Expression of fibroblast growth factor 13 (Fgf13) mRNA in bovine antral follicles and corpora lutea. Anim. Reprod. 2009;6:409–15.

Zhu Q, Zuo R, He Y, Wang Y, Chen ZJ, Sun Y, et al. Local regeneration of cortisol by 11β-HSD1 contributes to insulin resistance of the Granulosa cells in PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:2168–77.

Brinsden PR. A textbook of in vitro fertilization and assisted reproduction: the Bourn Hall guide to clinical and laboratory practice: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 1999:196.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19–25.

Buratini J, Costa I, Teixeira N, Castilho A, Price C. Fibroblast growth factor 13 gene expression in the bovine ovary. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:96.

Landriscina M, Bagalá C, Mandinova A, Soldi R, Micucci I, Bellum S, et al. Copper induces the assembly of a multiprotein aggregate implicated in the release of fibroblast growth factor 1 in response to stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25549–57.

Olsen SK, Garbi M, Zampieri N, Eliseenkova AV, Ornitz DM, Goldfarb M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) homologous factors share structural but not functional homology with FGFs. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34226–36.

Lu H, Shi X, Wu G, Zhu J, Song C, Zhang Q, et al. FGF13 regulates proliferation and differentiation of skeletal muscle by down-regulating Spry1. Cell Prolif. 2015;48:550–60.

Visser R, Landman EB, Goeman J, Wit JM, Karperien M. Sotos syndrome is associated with deregulation of the MAPK/ERK-signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49229.

Chabrolle C, Jeanpierre E, Tosca L, Rame C, Dupont J. Effects of high levels of glucose on the steroidogenesis and the expression of adiponectin receptors in rat ovarian cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2008;6:11.

Schoorlemmer J, Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors are intracellular signaling proteins. Curr Biol. 2001;11:793–7.

Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors: evolution, structure, and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:215–20.

Jung JG, Yi SA, Choi SE, Kang Y, Kim TH, Jeon JY, et al. TM-25659-Induced Activation of FGF21 Level Decreases Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in Skeletal Muscle via GCN2 Pathways. Mol Cells. 2015;38(12):1037–43.

Kim KH, Jeong YT, Oh H, Kim SH, Cho JM, Kim YN, et al. Autophagy deficiency leads to protection from obesity and insulin resistance by inducing Fgf21 as a mitokine. Nat Med. 2013;19:83–92.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81671518, Grant No. 81471424, Grant No. 81471029, Grant No. 81571499), Chinese National Key Basic Research Projects (Grant No. 2014CB943300) and Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gao feng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (Grant No. 20161413). Cultivating Funds of South Campus, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University (Grant No. 2017PYQA05).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL, SL: Conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, draft the article. TT, XL, QZ, YL: Acquisition of data. JM: Revising the article. YS: Conception and design of the study, WL: Conception and design of the study, final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital with informed consent. The informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Yes

Competing interests

The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Correlations between FF-FGF21 and oocyte development competence in PCOS patients. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, S., Tao, T. et al. Intrafollicular fibroblast growth factor 13 in polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship with androgen levels and oocyte developmental competence. J Ovarian Res 11, 87 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0455-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0455-3