Abstract

Background

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains a major contributor to mortality and morbidity after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). The updated recommendations suggest that rabbit antithymocyte globulin or anti-T-lymphocyte globulin (ATG) should be used for GVHD prophylaxis in patients undergoing matched-unrelated donor (MUD) allo-HSCT. More recently, using post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCY) in the haploidentical setting has resulted in low incidences of both acute (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD). Therefore, the aim of our study was to compare GVHD prophylaxis using either PTCY or ATG in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who underwent allo-HSCT in first remission (CR1) from a 10/10 HLA-MUD.

Methods

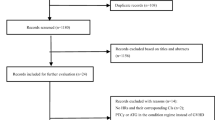

Overall, 174 and 1452 patients from the EBMT registry receiving PTCY and ATG were included. Cumulative incidence of aGVHD and cGVHD, leukemia-free survival, overall survival, non-relapse mortality, cumulative incidence of relapse, and refined GVHD-free, relapse-free survival were compared between the 2 groups. Propensity score matching was also performed in order to confirm the results of the main analysis

Results

No statistical difference between the PTCY and ATG groups was observed for the incidence of grade II–IV aGVHD. The same held true for the incidence of cGVHD and for extensive cGVHD. In univariate and multivariate analyses, no statistical differences were observed for all other transplant outcomes. These results were also confirmed using matched-pair analysis.

Conclusion

These results highlight that, in the10/10 HLA-MUD setting, the use of PTCY for GVHD prophylaxis may provide similar outcomes to those obtained with ATG in patients with AML in CR1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains a major contributor to mortality and morbidity after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) [1,2,3]. The pathogenesis of acute GVHD (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD) is complex [4, 5]. Acute GVHD is initiated when alloreactive donor immune cells recognize immunologically disparate antigens in the host. The risk of developing GVHD depends on the degree of HLA match, recipient age, graft source, underlying disease diagnosis, intensity of conditioning regimen, and also on GVHD prophylaxis. The updated recommendations suggest that rabbit antithymocyte globulin or anti-T-lymphocyte globulin (ATG) should be used for GVHD prophylaxis in patients undergoing matched-unrelated donor (MUD) allo-HSCT [6]. This recommendation is based on several high-level evidence publications showing a decreased rate of both acute and chronic GVHD [7,8,9,10]. However, ATG delays immune reconstitution and is associated with more infections, especially viral [11,12,13]. On the other hand, post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCY) is now well-established, successful, and widely utilized for GVHD prophylaxis after haploidentical allo-HSCT [14, 15]. The mechanism of PTCY has been described as inducing preferential elimination and clonal deletion of alloreactive T cells [16, 17]. Moreover, there is evidence supporting regulatory T cell importance in mediating long-term post-transplant tolerance and GVHD control with PTCY [18,19,20]. Since then, PTCY has been applied in other settings, including HLA-identical sibling or UD and mismatched unrelated donor (MMUD) [21,22,23,24]. In the 9/10 MMUD setting, PTCY use was described as effective anti-GVHD prophylaxis compared to ATG and likely to provide better outcomes in long-term disease control [25]. This increase in evidence of the positive impact of PTCY, prompted us to evaluate its practical clinical use in allo-HSCT with MUD.

In the current study, we retrospectively analyzed results of allo-HSCT transplantation using 10/10 MUD in a homogenous population of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients in first complete remission (CR1), comparing the outcomes of PTCY versus ATG as GVHD prophylaxis.

Methods

This is a retrospective study from the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), which is a working group of more than 600 transplant centers, mostly located in Europe, that are required to report annually all consecutive transplantations and follow-up data. Data from all EBMT centers are entered, managed, and maintained in a central online database. There are no restrictions on centers for reporting data, except for those required by law on patient consent, data confidentiality, and accuracy. Quality control measures include several independent systems: confirmation of the validity of the entered data by the reporting team, selective comparison of the survey data with MED-A data sets in the EBMT registry database, cross-checking with the National Registries, and regular in-house and external data audits. Patients provide informed consent authorizing the use of their personal information for research purposes. Each patient provides consent for transplant according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the ALWP of the EBMT.

Eligibility criteria

In order to be included in this study, patients had to fulfill all of the following criteria: age ≥ 18 years; diagnosed with AML and undergoing first HSCT in CR1; from a 10/10 MUD (patients and donors should have HLA A, B, C, and DRB1 and DQB1 allelic typing performed). Graft source of stem cells was the peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) or bone marrow (BM). In the ATG group, allo-HSCT patients received 5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin. All patients underwent transplantation between January 2010 and December 2017.

Definitions

Endpoints of the study were the cumulative incidence of acute GVHD grade II–IV and chronic GVHD, leukemia-free survival (LFS), overall survival (OS), refined GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS), cumulative incidences of relapse (RI), and non-relapse mortality (NRM). Acute GVHD was graded according to the modified Glucksberg criteria [26] and cGVHD according to the revised Seattle criteria [27].

Engraftment was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count greater than or equal to 0.5 × 109/L for three consecutive days. The probability of being alive without evidence of relapse or progression defined LFS. OS was defined as the time from allo-HSCT to death, regardless of the cause. Refined GRFS was defined as being alive with neither grade III–IV aGVHD nor severe cGVHD nor disease relapse at any time point 15. Death without evidence of relapse defined NRM [28].

The cytogenetic risk was defined according to the MRC criteria 11. Performance status was graded according to the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale and was defined as poor when it was < 90%. The conditioning regimen was defined according to data reported by the EBMT centers as myeloablative (MAC) or reduced-intensity (RIC) according to the EBMT definition 12.

Statistical analysis

Median values, inter-quartiles ranges (IQR), and minimum and maximum were used to express continuous variables while frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Patient-, disease-, and transplant-related variables of the groups were compared using the chi-square or Fischer’s exact test for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables [29].

Acute and chronic GVHD, RI, and NRM were calculated using the cumulative incidence estimator to accommodate competing risks. For NRM, relapse was the competing risk, and for RI, the competing risk was death without relapse. To study acute and chronic GVHD, we considered relapse and death to be competing events. The probabilities of OS, LFS, and GRFS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate analyses were done using Gray’s test for cumulative incidence functions and the log-rank test for OS, GRFS, and LFS. A Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate regression. All variables differing significantly between the two groups, or variables deemed conceptually important were included in the Cox model: ATG versus PTCY, age, year of transplant, time from diagnosis to transplant, secondary versus de novo AML, cytogenetics, KPS, conditioning regimen, female donor to male recipient versus other, stem cell source, CMV serology status for both patients, and donors. In order to test for a center effect, we introduced a random effect or frailty for each center into the model [30, 31]. Results were expressed as the hazard ratio (HR) with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). P values were two-sided. Propensity score matching was also performed in order to confirm the results of the main analysis 19. Each patient identified as having received PTCY was matched with two patients who had received ATG. The following factors were included in the propensity score model: age, time from diagnosis to transplant, secondary AML, cytogenetics, conditioning intensity, female donor to male recipient, patient, and donor CMV serology status. All tests were two-sided. The type I error rate was fixed at 0.05 for the determination of factors associated with time-to-event outcomes. Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 24 (SPSS Inc./IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and R 3.6.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) software packages.

Results

The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 174 and 1452 patients receiving PTCY and ATG, respectively, fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The median follow-up period was 20.5 (IQR 6.9–32.6) months in the PTCY group as compared to 33.2 (17.6–52.7) months in the ATG group (p < 0.001). Patients in the PTCY group were younger (median age 46 versus 56 years, p < 0.001) and had undergone allo-HSCT more recently (median year of allo-HSCT 2016 versus 2014, p < 0.001). Time from diagnosis to allo-HSCT was similar in both groups. Peripheral blood stem cells were the more frequently used stem cell source, with no significant difference of utilization among the 2 groups. Conditioning regimen intensity was comparable in the two groups. The only ATG brand used was Thymoglobuline®. Two or three additional immunosuppressive agents were used in 55% and 85% of patients receiving PTCY and ATG, respectively (supplementary data, Table S1).

Comparative analysis of transplant outcomes with ATG or PTCY

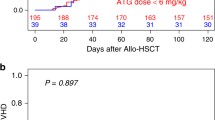

The results of uni- and multivariate analyses are summarized in Tables 2, 3, and 4. No statistically significant differences were observed between the PTCY and ATG groups for RI, NRM, LFS, OS, and GRFS (Fig. 1). These results were confirmed using matched-pair analysis (Tables S2 and S3).

Engraftment and GVHD

The proportion of patients achieving neutrophil engraftment at 100 days was similar in the PTCY and ATG groups (98.8% versus 99.2%, respectively, p = 0.65). The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 21 and 18 days in PTCY and ATG groups, p < 0.001.

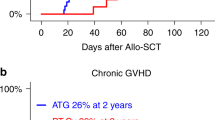

There were no significant differences in CI at 100 days of aGVHD (grades II–IV or III–IV), cGVHD, or ext cGVHD between the PTCY and the ATG group (Table 2) (Fig. 2). In the Cox model and in propensity score (data not shown), there was not a significant statistical difference between both groups, considering aGVHD II-IV, aGVHD III-IV, cGVH, and extensive cGVHD.

Regardless of the use of PTCY or ATG, a RIC regimen was independently associated with a lower risk of grade II–IV acute GVHD, female donor to male recipient and KPS < 90 associated with a higher risk of grade III–IV acute GVHD and patient CMV positivity with a higher risk of chronic GVHD (Table 3).

OS, LFS, and GRFS

On univariate analysis, there were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to OS, LFS, or GRFS (Table 4). The GRFS was also similar, accounting for 42% in the PTCY and 49% in the ATG group (p = 0.2) which results were also confirmed in the multivariate analysis (Table 5). Regardless of the use of PTCY or ATG, a diagnosis of secondary AML and the presence of adverse cytogenetics were associated with lower probabilities of LFS, OS, and GRFS. Older age was also associated with a lower OS and LFS.

Relapse incidence and NRM

The 2-year RI and NRM rates did not differ between the two groups at 2 years. This was confirmed in the multivariate analysis where, regardless of the immunosuppressive agent used, adverse cytogenetics at diagnosis was independently associated with a higher risk of relapse. Female donor to male recipient transplants were associated with a lower risk of relapse. Older age, secondary AML patients, and transplants from a female donor to a male recipient were independently associated with a higher NRM (Table 5).

The main cause of death was disease recurrence in 47% of patients receiving PTCY and 39% of those receiving ATG. Infection accounted for 17% of deaths in the PTCY group and 22% of the ATG group. Cardiac toxicity was fatal for 1.9% of patients who received PTCY and 1.2% who received ATG (results not shown).

Discussion

We have compared the impact of PTCY with that of ATG, (Thymoglobulin), in the conditioning regimen for patients undergoing transplantation from 10/10 MUD. First, we observed that PTCY and ATG had comparable cumulative incidences of aGVHD II–IV and grades III–IV with between 8 and 9% in each group. The impact was also similar considering cGVHD and extensive cGVHD. Considering ATG, these results were consistent with randomized clinical trials evaluating the use of ATG in HSCT from unrelated donors [7, 9, 10, 32, 33]. Most data about using PTCY in MUD are from studies of intensive pre-transplant conditioning regimens and mostly unmanipulated BM grafts. Luznik et al. reported data from 117 patients with high-risk hematological neoplasms transplanted from HLA-matched-related donors and MUDs after conditioning with busulfan and cyclophosphamide [34]. At 2 years after transplantation, the cumulative incidence of cGVHD for recipients of unrelated donor grafts was 11% (95% CI, 3–25%). It should be noted that PTCY was the only GVHD prophylaxis used, and BM was the only graft source used. Ruggeri et al. reported outcomes of 423 patients who received PTCY alone or in combination with additional drugs after HLA-matched sibling (N = 241) or MUD (N = 182) transplants using MAC or RIC [24]. In their study, 64% received PBSC. On multivariate analysis, PBSC was associated with a significantly higher risk of cGVHD and extensive cGVHD but had no impact on the other outcomes. We did not find any impact of source graft in our study; however, almost 90% of the patients received PBSC. Our results suggest that PTCY is an alternative to the recommended clinical practice of ATG in MUD. One hypothesis is that the degree of disparity between a recipient with a 10/10 HLA matched unrelated donor is low and the effect of PTCY of minimizing other HLA major or minor histocompatibility mismatches is not needed in this situation.

The second point is the absence of a significant difference at 2 years, in terms of NRM, which was quite low in both groups (16.7% and 15.2% for PTCY and ATG groups, respectively). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, we could not compare the CI of infections especially viral infections. Indeed, the use of ATG has been associated with EBV reactivation [9, 35]. The comparison between PTCY and ATG on EBV reactivation should be evaluated in prospective studies. In our study, however, the incidence of death from infection was similar in the two groups. Likewise, it would be of interest to report cardiac complications especially in the PTCY group, noting, that a similar incidence of death from cardiac failure was observed in both of our groups. RI was not statistically different in the two groups. Retrospective or non-randomized studies have reported conflicting results on the impact of ATG in the setting of RIC transplants. In particular, higher doses of ATG have been associated with a higher risk of relapse, thus leading to a decreased disease-free survival [11, 36]. On the contrary, Baron et al. found that the use of ATG was not significantly associated with a higher risk of relapse in patients with AML who underwent PBSC transplantation from HLA-identical siblings after RIC in CR1 [37]. Two other studies of our group did not find the impact of ATG on relapse even in high-risk AML [38, 39]. Because of lack of statistical power, we could not study the impact of PTCY or ATG with respect to the conditioning regimen intensity; however, we decided to include only patients who received a low dose of ATG (5 mg/kg in total), which has not been associated with a higher incidence of relapse [40, 41].

Conclusions

The use of PTCY for GVHD prophylaxis resulted in similar outcomes to those seen with ATG for patients who underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation for AML in CR1 with a 10/10 HLA-matched donor. The impact of the number, type, and schedule of the associated immunosuppressive agents needs further investigation. Due to the retrospective nature and the limitations of our analysis, including the schedule of ATG or PTCY and the lack of aforementioned data (e.g., infections, disease biology), our results need to be confirmed by prospective controlled studies. A precise knowledge of specific morbidity induced by each type of prophylaxis would be of great interest in clinical practice to aid the choice between PTCY or ATG when considering comorbidities and infection risk. Our results do, however, provide further proof that both ATG and PTCY are valid GVHD prophylactic strategies for transplants from 10/10 HLA-MUD.

Availability of data and materials

EB, ML, AN, and MM had full access to all the data in the study (available upon data-specific request).

Abbreviations

- aGVHD:

-

Acute graft-versus-host disease

- allo-HSCT:

-

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- ATG:

-

Anti-thymocyte globulin

- BM:

-

Bone marrow

- cGVHD:

-

Chronic graft-versus-host disease

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- CR:

-

Complete remission

- IR:

-

Cumulative incidence of relapse

- GRFS:

-

Graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival

- Interm:

-

Intermediary

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KPS:

-

Karnovsky Performance Status

- LFS:

-

Leukemia-free survival

- MAC:

-

Myeloablative conditioning regimen

- MUD:

-

Matched-unrelated donor

- NRM:

-

Non-relapse mortality

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PBSC:

-

Peripheral blood stem cell

- PTCY:

-

Posttransplantation cyclophosphamide

- RIC:

-

Reduced intensity conditioning regimen

- secAML:

-

Secondary acute myeloid leukemia

References

Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Wang Z, Sobocinski KA, Jacobsohn D, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(16):2230–9.

Martin PJ, Counts GW Jr, Appelbaum FR, Lee SJ, Sanders JE, Deeg HJ, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):1011–6.

Lee CJ, Kim S, Tecca HR, Bo-Subait S, Phelan R, Brazauskas R, et al. Late effects after ablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adolescent and young adult acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020;4(6):983–92.

Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Pathophysiology of chronic graft-versus-host disease and therapeutic targets. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2565–79.

Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease - biologic process, prevention, and therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2167–79.

Penack O, Marchetti M, Ruutu T, Aljurf M, Bacigalupo A, Bonifazi F, et al. Prophylaxis and management of graft versus host disease after stem-cell transplantation for haematological malignancies: updated consensus recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(2):e157–e67.

Finke J, Bethge WA, Schmoor C, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, et al. Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):855–64.

Finke J, Schmoor C, Bethge WA, Ottinger H, Stelljes M, Volin L, et al. Long-term outcomes after standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-human-T-lymphocyte immunoglobulin in haemopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: final results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(6):e293–301.

Walker I, Panzarella T, Couban S, Couture F, Devins G, Elemary M, et al. Pretreatment with anti-thymocyte globulin versus no anti-thymocyte globulin in patients with haematological malignancies undergoing haemopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):164–73.

Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, Guidi S, Alessandrino PE, di Bartolomeo P, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors: 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Blood. 2001;98(10):2942–7.

Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, Kan F, Artz A, Champlin RE, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117(25):6963–70.

Wagner JE, Thompson JS, Carter SL, Kernan NA. Unrelated Donor Marrow Transplantation T. Effect of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on 3-year disease-free survival in recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (T-cell Depletion Trial): a multi-centre, randomised phase II-III trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9487):733–41.

Mohty M. Mechanisms of action of antithymocyte globulin: T-cell depletion and beyond. Leukemia. 2007;21(7):1387–94.

Luznik L, O'Donnell PV, Symons HJ, Chen AR, Leffell MS, Zahurak M, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(6):641–50.

Bashey A, Zhang X, Sizemore CA, Manion K, Brown S, Holland HK, et al. T-cell-replete HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for hematologic malignancies using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide results in outcomes equivalent to those of contemporaneous HLA-matched related and unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1310–6.

Mayumi H, Good RA. Long-lasting skin allograft tolerance in adult mice induced across fully allogeneic (multimajor H-2 plus multiminor histocompatibility) antigen barriers by a tolerance-inducing method using cyclophosphamide. J Exp Med. 1989;169(1):213–38.

Eto M, Mayumi H, Tomita Y, Yoshikai Y, Nishimura Y, Nomoto K. Sequential mechanisms of cyclophosphamide-induced skin allograft tolerance including the intrathymic clonal deletion followed by late breakdown of the clonal deletion. J Immunol. 1990;145(5):1303–10.

Ganguly S, Ross DB, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Kanakry CG, Blazar BR, Levy RB, et al. Donor CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are necessary for posttransplantation cyclophosphamide-mediated protection against GVHD in mice. Blood. 2014;124(13):2131–41.

Kanakry CG, Ganguly S, Zahurak M, Bolanos-Meade J, Thoburn C, Perkins B, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase expression drives human regulatory T cell resistance to posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(211):211ra157.

Wachsmuth LP, Patterson MT, Eckhaus MA, Venzon DJ, Gress RE, Kanakry CG. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide prevents graft-versus-host disease by inducing alloreactive T cell dysfunction and suppression. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(6):2357–73.

Mielcarek M, Furlong T, O'Donnell PV, Storer BE, McCune JS, Storb R, et al. Posttransplantation cyclophosphamide for prevention of graft-versus-host disease after HLA-matched mobilized blood cell transplantation. Blood. 2016;127(11):1502–8.

Carnevale-Schianca F, Caravelli D, Gallo S, Coha V, D'Ambrosio L, Vassallo E, et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide and tacrolimus-mycophenolate mofetil combination prevents graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic peripheral blood hematopoietic cell transplantation from HLA-matched donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(3):459–66.

Jorge AS, Suarez-Lledo M, Pereira A, Gutierrez G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Rosinol L, et al. Single antigen-mismatched unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using high-dose post-transplantation cyclophosphamide is a suitable alternative for patients lacking HLA-matched donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(6):1196–202.

Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Bacigalupo A, Afanasyev B, Cornelissen JJ, Elmaagacli A, et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in HLA matched sibling or matched unrelated donor transplant for patients with acute leukemia, on behalf of ALWP-EBMT. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):40.

Battipaglia G, Labopin M, Kroger N, Vitek A, Afanasyev B, Hilgendorf I, et al. Posttransplant cyclophosphamide vs antithymocyte globulin in HLA-mismatched unrelated donor transplantation. Blood. 2019;134(11):892–9.

Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 consensus conference on acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–8.

Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9(4):215–33.

Kanate ANA, Savani B. Summary of scientific and statistical methods, study endpoints and definitions for observational and registry-based studies in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Hematol Int. 2020;2(1):2–4.

Kaplan E, Mayer P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat. 2008;53(282):457–81.

Hougaard P. Frailty models for survival data. Lifetime data analysis. 1995;1(3):255–73.

Andersen PK, Klein JP, Zhang MJ. Testing for centre effects in multi-centre survival studies: a Monte Carlo comparison of fixed and random effects tests. Statistics in medicine. 1999;18(12):1489–500.

Soiffer RJ, Kim HT, McGuirk J, Horwitz ME, Johnston L, Patnaik MM, et al. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, phase III clinical trial of anti-T-lymphocyte globulin to assess impact on chronic graft-versus-host disease-free survival in patients undergoing HLA-matched unrelated myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4003–11.

Kroger N, Solano C, Wolschke C, Bandini G, Patriarca F, Pini M, et al. Antilymphocyte globulin for prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):43–53.

Luznik L, Bolanos-Meade J, Zahurak M, Chen AR, Smith BD, Brodsky R, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide as single-agent, short-course prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;115(16):3224–30.

Peric Z, Cahu X, Chevallier P, Brissot E, Malard F, Guillaume T, et al. Features of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) reactivation after reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2011;25(6):932–8.

Crocchiolo R, Esterni B, Castagna L, Furst S, El-Cheikh J, Devillier R, et al. Two days of antithymocyte globulin are associated with a reduced incidence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in reduced-intensity conditioning transplantation for hematologic diseases. Cancer. 2013;119(5):986–92.

Baron F, Labopin M, Blaise D, Lopez-Corral L, Vigouroux S, Craddock C, et al. Impact of in vivo T-cell depletion on outcome of AML patients in first CR given peripheral blood stem cells and reduced-intensity conditioning allo-SCT from a HLA-identical sibling donor: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(3):389–96.

Nagler A, Dholaria B, Labopin M, Socie G, Huynh A, Itala-Remes M, et al. The impact of anti-thymocyte globulin on the outcomes of patients with AML with or without measurable residual disease at the time of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2020;34(4):1144–53.

Ofran Y, Beohou E, Labopin M, Blaise D, Cornelissen JJ, de Groot MR, et al. Anti-thymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in patients with intermediate- or high-risk acute myeloid leukaemia undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission - a survey on behalf of the Acute Leukaemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2019;184(4):643–6.

Remberger M, Ringden O, Hagglund H, Svahn BM, Ljungman P, Uhlin M, et al. A high antithymocyte globulin dose increases the risk of relapse after reduced intensity conditioning HSCT with unrelated donors. Clinical transplantation. 2013;27(4):E368–74.

Devillier R, Labopin M, Chevallier P, Ledoux MP, Socie G, Huynh A, et al. Impact of antithymocyte globulin doses in reduced intensity conditioning before allogeneic transplantation from matched sibling donor for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the acute leukemia working party of European group of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(4):431–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emmanuelle Polge from the ALWP office, the EBMT, and all the participating centers of the EBMT and national registries for providing patients for the study. They also thank the data managers for their valuable contribution (Additional file 1).

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B. and M.L. designed the study; M.L. performed the statistical analyses; E.B. wrote the manuscript; B.S., A.N., and M.M. revised the manuscript; B.A., J.C., E.M., G.V.G., M.R., F.C., L.G., D.B., E.F., M.M., S.M., C.B., R.N., E.D., A.R., M.S., A.S., B.S., and S.G. were the principal investigators at the centers recruiting the largest numbers of patients for the study. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site and complied with country-specific regulatory requirements. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of the Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Patients provide informed consent authorizing the use of their personal information for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Combination of immunosuppressive drugs. Table S2. Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics after matched-pair analysis. Table S3. Two-year survival outcomes and CI of GVHD after matched-pair analysis. EBMT participating centers

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Brissot, E., Labopin, M., Moiseev, I. et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide versus antithymocyte globulin in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation from 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donors. J Hematol Oncol 13, 87 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00923-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00923-0