Abstract

Background

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is rare in children. Although complex karyotype (CK) defined as ≥ 3 cytogenetic abnormalities is an adverse risk factor in adult AML, its prognostic impact on childhood AML remains to be determined.

Results

We studied the prevalence, cytogenetic and mutational features, and outcome impact of CK in a cohort of 284 Chinese children with de novo AML. Thirty-four (12.0%) children met the criteria for CK-AML with atypical CK being more frequent than typical CK featured with -5/5q-, -7/7q-, and/or 17p aberration. Mutational prevalence was low and co-occurrence mutants were uncommon. Children with CK-AML showed shorter overall survival (OS) (5-year OS: 26.7 ± 10.6% vs. 37.5 ± 8.6%, p = 0.053) and event-free survival (EFS) (5-year EFS: 26.7 ± 10.6% vs. 38.8 ± 8.6%, p = 0.039) compared with those with intermediate-risk genetics. Typical CK tended to correlate with a decreased OS than atypical CK (5-year OS: 0 vs. 33 ± 12.7%.; p = 0.084), and CK with ≥ 5 cytogenetic aberrations was associated with an inferior survival compared with CK with ≤ 4 aberrations (5-year OS: 13.6 ± 11.7% vs. 50.0 ± 18.6%; p = 0.040; 5-year EFS: 13.6 ± 11.7% vs. 50.0 ± 18.6%; p = 0.048).

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate CK as an adverse risk factor for reduced survival in childhood AML. Our findings shed light on the cytogenetic and mutational profile of childhood CK-AML and would inform refinement of risk stratification in childhood AML to improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a group of clonal hematopoietic neoplasms that are characterized by aberrations in maturation, proliferation, and survival in the stem and progenitor cell compartments. Childhood AML is a relatively rare disease that accounts for 15%–20% of acute leukemias in children. Despite considerable progress have made in treating children with AML, about 30% of patients still experience relapse and do not survive beyond five years [1, 2]. Identification of additional genetic biomarkers predicting prognosis in childhood AML is needed to improve outcomes.

Cytogenetic and molecular mutational features play an important role in AML risk stratification [3, 4]. Complex karyotype (CK), commonly defined as three or more chromosomal aberrations in the absence of the WHO recurrent genetic aberrations of t(8;21)(q22;q22), inv(16)(p13.1q22) /t(16;16) (p13.1;q22); t(15;17)(q22;q12); t(9;11)(p22;q23), t(6;9)(p23;q34), inv(3)(q21q26)/t(3;3)(q21;q26), and t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) [5,6,7,8], is considered as an adverse risk factor in adult AML, but its prognostic impact on childhood AML remains to be determined [5, 9]. Differences in AML genetic profile between adults and children are well documented [10,11,12], and their impact on outcome may differ among age groups [6, 13]. There is also evidence to suggest geographic heterogeneity of AML cytogenetic and molecular features worldwide [14,15,16,17]. So far, few studies have been focused on the cytogenetic and molecular profile of childhood CK-AML, largely owing to the rarity of AML in children and none in a Chinese population [18,19,20].

Here, we report a study that investigated the prevalence, features, and clinical correlation of cytogenetic and mutational characteristics of CK-AML in a cohort of 284 children with AML. Our study showed CK was associated with decreased survival in childhood AML and its impact on outcome correlated with the number of chromosomal aberrations. These results would aid in informing risk stratification of childhood AML to guide risk-adapted therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

A total of 284 patients (≤ 18 years old) with de novo AML were enrolled in the study between 2007 and 2018 at Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in China. The diagnoses were based on histological, cytogenetics, and immunophenotyping analyses of bone marrow. The patients were treated with daunorubicin/cytarabine/etoposide (DAE)-based regimen following the protocols of the Pediatric Hematology Group of Chinese Medical Association [21]. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cytogenetic analysis

G-banded karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies were performed according to the standard procedures [22]. A complete study required analysis of at least 15 metaphase cells. The FISH probes included RUNX1/RUNX1T1/t(8;21)(q22;q22), CEBP/MYH11/inv(16)(p13.1q22) /t(16;16) (p13.1;q22); PML/RARA/t(15;17)(q22;q12); BCR/ABL1/t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), and KMT2A(MLL)/11q23 rearrangement (Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, Illinois). A complex karyotype was defined as three or more chromosomal aberrations in the absence of the WHO recurrent AML genetic aberrations of t(8;21)(q22;q22), inv(16)(p13.1q22) /t(16;16) (p13.1;q22); t(15;17)(q22;q12), t(6;9)(p23;q34.1), KMT2A(MLL)/11q23 rearrangement, and t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) [19]. An unbalanced aberration involving two or more chromosomes was counted as two abnormalities [23, 24]. Down syndrome AML was excluded from the study. CK patients with -5/5q-, -7/7q-, and/or 17p aberrations were assigned as typical CK while the others were deemed as atypical CK. Karyotype designation was in accordance with the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature 2016 [25].

Risk classification was following the modified US Children Oncology Group (COG) AML risk stratification scheme: low risk features included t(8;21)(q22;q22), inv(16)(p13.1q22) /t(16;16) (p13.1;q22); t(15;17)(q22;q12), mutated NPM1,and/or biallelic mutated CEBPA; high-risk factors were -7, -5/5q-, t(6;9)(p23;q34), t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), inv(3)(q21q26.2)/t(3;3)(q21;q26.2), KMT2A/11q23 rearrangement except t(9;11)(p21.3;q23.3), and FLT3-ITD; and intermediate-risk features were those without the high or low-risk features [20, 23, 26].

Gene mutation analysis

Total RNA was extracted from bone marrow samples using the Tiangen RNAprep Pure Blood Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), and used as the template for cDNA synthesis with the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). DNA fragments covering the mutational hotspots were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified from cDNA following the conditions previous described [27,28,29,30,31,32]. The PCR products were analyzed by Sanger sequencing, and the PCR products containing mutations were repeated at least once to confirm the presence of the identified mutations. Some mutant PCR products were subcloned into the pBackZero-T Vector (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Dalian, China) for further sequencing. PolyPhen and SIFT programs as well as COSMIC database (release v89, 15th May 2019) were employed to predict the pathogenicity of variants [33, 34]. Gene mutation hotspots analyzed in this study included FLT3 (exons 14–15), NPM1 (exon 12), WT1 (exons 7 and 9), NRAS (exons 1–2), KRAS (exons 1–2), IDH1 (exon 4), IDH2 (exon 4), KIT (exons 8, 10, 11 and 17), CEBPA (exon 1), CCDN1 (exon 5), ASXL2 (exons 11–12), DHX15 (exon 3), GATA2 (exons 4–6), and DNMT3A (exon 2) [27,28,29,30,31,32].

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were compared using chi-square (χ2), Fisher’s exact, or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Complete remission (CR) was defined as bone marrow with less than 5% blasts and evidence of regeneration of normal hematopoietic cells. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to death or last contact. Event-free survival (EFS) was the time between diagnosis and occurrence of the first event (i.e., failure to achieve complete remission, relapse, secondary tumor, or death of any cause). OS and EFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier analysis, and the differences were compared using the log-rank test. A p value of ≤ 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistical significance. The analyses were performed with SPSS software package v17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Childhood CK-AML cytogenetics

Of 284 patients in the cohort, 225 (79.2%) cases showed clonal cytogenetic aberrations. One hundred forty-three were classified as low-risk, 109 intermediate-risk, and 32 high-risk. Thirty-four (12.0%) patients met the criteria for CK (Additional file 1: Table 1). Among the patients with CK-AML, seven were less than 2 years old and 27 were at two years or older, resulting in CK incidences of 20.6% and 79.4% in children younger than two years and older than two years, respectively. Nine CK cases were typical CK and 25 atypical CK. The average number of aberrations in the typical and atypical CK subgroups were 6 [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] and 4 [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.025). Sixteen CK cases harbored three to four abnormalities and the others had five or more aberrations. Multiple cytogenetic clones defined as two or more clones were observed in 17 (50%) patients with CK-AML.

Clinical and gene mutation characteristics of childhood CK-AML

There were no differences in clinical features between the CK and intermediate-risk groups except that patients with CK-AML tended to be younger (2.5 yrs. vs. 5.0 yrs., p = 0.031) (Table 1). Compared with children with CK-AML, patients with intermediate-risk features had a higher NRAS mutation incidence although the difference was not statistically significant (3% vs. 18%; p = 0.079) (Table 1). Among the patients with CK-AML, WT1 gene had the highest mutational incidence (13%) followed by CEBPA, FLT3/ITD, and IDH1 genes (6.0% each), and none was observed in NPM1, KIT, CCND1, IDH2, ASXL2, DHX15, and DNMT3A genes (Table 1). Patients with atypical CK-AML were likely to have higher blasts in bone marrow than those with typical CK-AML (73% vs. 68%; p = 0.08) while there were no differences in other clinical and molecular features between the two groups (Additional file 2: Table 2). Similar clinical and mutational features were observed between CK with ≤ 4 and ≥ 5 aberrations (Additional file 3: Table 3). CK-AML patients with a single clone were younger (2.0 vs. 3.0 yrs., p < 0.001) and had a higher percentage of blasts in marrow (70% vs. 68%; p < 0.001) compared to those with two or more clones, but no difference in gene mutational frequencies (Table 2). Of thirteen common AML genes examined in the CK-AML cohort, concomitant mutants were observed only in one patient (CEBPA and NKRS) (Fig. 1).

Impact of CK on childhood AML outcomes

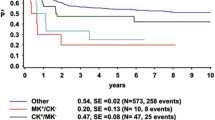

Outcome information was available from 60 patients in the intermediate-risk group and 20 patients in the CK group. The median follow-up was 15 months (range 1–91 months). Compared to those with intermediate-risk AML, patients with CK-AML seemed less likely to reach complete remission (60% vs. 83%; p = 0.076) (Table 1), and had a trend for shorter survivals (5-year OS: 26.7 ± 10.6% vs. 37.5 ± 8.6%, p = 0.053; 5-year EFS: 26.7 ± 10.6% vs. 38.8 ± 8.6%, p = 0.039) (Fig. 2). Children with typical CK-AML showed a trend for decreased OS (5-year OS: 0 vs. 33 ± 12.7%.; p = 0.084) but no difference in EFS (5-year EFS: 0 vs. 33.0 ± 12.7%; p = 0.14) compared with those with atypical CK-AML. Patients with ≥ 5 chromosome aberrations had an inferior OS and EFS (5-year OS: 13.6 ± 11.7% vs. 50.0 ± 18.6%; p = 0.040; 5-year EFS: 13.6 ± 11.7% vs. 50.0 ± 18.6%; p = 0.048) than ones with ≤ 4 aberrations, indicating a positive correlation between the number of chromosomal aberrations and worsen survivals. No differences in CR and relapse rates, as well as survivals, were observed between CK with a single and multiple clones (5-year OS: 18.9 ± 15.3% vs. 41.7 ± 17.3%; p = 0.92; 5-year EFS: 18.5 ± 16.1% vs. 33.3 ± 15.7%; p = 0.52) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Outcome data were available on three CK-AML cases with mutant WT1 gene, two relapsed, one died in 8 months and the other in 26 months. Another child was still alive at the last contact of six and half years after diagnosis.

Comparison of overall survivals (OS) and even-free survivals (EFS) of AML with complex karyotype (CK) and intermediate-risk (a and b), typical and atypical CK (c and d), CK with ≤ 4 and ≥ 5 aberrations (e and f), and CK with a single and multiple clones (g and h). CK: complex karyotype; abn: abnormality

Discussion

In the past decades significant progresses have been made in treating childhood AML. But one-third of children with AML relapse and do not survive beyond 5 years [1, 2]. Cytogenetics is a major factor in AML risk classification which is important in guiding risk-adapted treatment [3, 4]. So far our knowledge of AML cytogenetics has been primarily derived from studies on adult AML and little is known about features and clinical correlation of CK in childhood AML, mainly owing to the rarity of the disease [18,19,20].

The prevalence of CK-AML in our study cohort, 12.0%, is comparable to 9.5% reported in another AML study in Chinese children [35]. In a study of children with AML in the United Kingdom, Harrison and colleagues observed a high CK incidence of 17.7%, but the study included CK with the WHO recurrent AML genetic aberrations such as t(8;21) and inv(16)(13). A relatively high CK prevalence, 18.5%, was also documented in a small study on Korean children [36]. In another study of 642 European children with AML, Rasche and colleagues reported a CK frequency of 9% [20]. In the present study, we also observed a distinct age-associated CK distribution with a higher incidence in toddlers than in young children and adolescents (20.0% in < 2 yrs. vs. 10.8% in ≥ 2 yrs). This is in agreement with the observation from a study of German children which showed similar distribution between the two age groups [37].

CK is considered an adverse risk factor in adult AML but its role in childhood AML remains inconclusive [3]. In our cohort most children with CK-AML reached CR, which is in line with the findings from other studies [20, 38, 39], but had shorter survivals compared with those with intermediate-risk features, demonstrating that CK is an adverse risk factor in childhood AML. Bager et al. reported reduced OS and EFS in children with CK-AML than those with non-CK-AML [18]. In their study, the comparator group, children with non-CK, also included ones with the t(8;21) and inv(16) which are associated with favorable outcomes. Therefore, it can’t definitively distinguish whether the improved survivals observed in non-CK group were due to the presence of the favorable cytogenetics in the comparator group or reduced survivals in the CK group were due to the worse effect of CK on AML than intermediate-risk cytogenetics in the comparator group. In another study of 59 children with CK-AML, Rasche and colleagues found no difference in survivals between children with CK-AML and those with either intermediate or low-risk features [20].

In adult CK-AML, shorter survival and a higher relapse rate have been associated with typical CK compared with atypical CK [19, 40]. We found no difference in EFS between typical CK and atypical CK groups among our patients but OS tended to be reduced in the typical CK-AML group. In a previous study of British children with CK-AML, Grimwade and colleagues described comparable outcomes between typical and atypical CK-AML [13]. In that study, the CK cohort also included the known favorable cytogenetics of t(8;21) and inv(16) which could influence the outcomes in either or both subgroups and thus, might be a confounding factor in assessing the impact of typical and atypical CK on AML outcomes [13]. Additional studies are necessary to further assess whether typical and atypical AML are two distinct disease entities with different outcomes in childhood AML. Furthermore, our study reveals CK with ≥ 5 aberrations is associated with shorter survivals than CK with ≤ 4 aberrations, suggesting a correlation of a higher number of chromosomal abnormalities with a worse prognosis. A similar relationship was also observed in childhood CK-AML in the study of Rasche and colleagues who reported significantly reduced OS among children with CK having > 5 aberrations compared to those with ≤ 5 abnormalities but no difference in EFS between the two groups [20]. More recently, Bager et al. observed a longer 5-year OS in CK with five or more aberrations and comparable EFS compared to CK with 3–4 aberrations [18]. Future studies are warranted to determine whether complex karyotypes with five or more chromosomal aberration is associated with worse outcome in childhood CK-AML.

In the present study, there were considerable number of CK cases harboring more than one cytogenetic clone but no differences in outcomes between ones with a single and multiple clones. Recent mutational studies using next-generation sequencing demonstrate that mutations at diagnosis play a critical role in leukemogenesis but mutational evolution during disease course is also important in influencing outcomes. These observations underscore the importance of continuous genetic profiling throughout the disease course in guiding optimal therapy to improve outcomes [41, 42].

Thus far, there is limited information on mutational profile of CK-AML and no mutational profiling of childhood CK-AML has been reported in the literature [19]. The results from our study show that atypical CK is more common than typical CK in childhood AML compared to high frequency of typical CK than atypical CK reported in adults [19, 40, 43]. Analysis of more than a dozen of common AML genes examined in our pediatric AML cohort showed that mutant incidences were low and concomitant mutants were rare. In a study of 81 genes in adult CK-AML, Mrozek and colleagues reported an average of two mutants per case [19]. Considering the fact that mutational frequencies in AML increase with aging, our results along with others demonstrate that molecular aberrations are uncommon in CK-AML [37]. Although the mutated FLT3/ITD and IDH1 gene incidences in our childhood CK-AML cohort were comparable to those observed in adult counterparts, mutant WT1 and CEBPA gene incidences were higher in our cohort than adult patients (WT1: 13.0% vs. 2.9%; CEBPA: 6.0% vs. 1.5%) [19]. Of three CK-AML patients carrying WT1 gene mutation with outcome information available, two relapsed and died at 8 and 26 months, respectively, after diagnosis. These were similar to the observations reported by others that mutant WT1 gene is associated with decreased survivals and high relapse [44, 45]. Finally, TP53 gene aberrations have been reported in 40%-50% of adult patients with CK-AML [19, 46]. TP53 mutational analysis was not performed in the present study, and we only observed one CK-AML case (2.9%) with a 17p13.1 deletion by cytogenetic analysis. Taken together, our results show a difference in cytogenetic and mutational profiles between childhood and adult CK-AML, which is in accordance with findings in other AML subtypes [37].

Differences in results between our study and others are likely attributed to variation in the composition of study cohorts including the number of patients, age, treatment modalities, criteria for complex karyotype (≥ 3 vs. ≥ 5 aberrations), geographic locations, ethnic groups, methods used in mutation analysis, and the number of genes examined. Our results need to be validated by future studies of large cohorts of children with CK-AML.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, no such studies have been reported in the literature and ours is the first in the Chinese population. Our results demonstrate for the first time that among Chinese children with CK-AML, atypical CK was more frequent than typical CK, mutational incidences were low and concomitant mutants were uncommon. CK-AML had reduced EFS and OS compared with intermediate-risk AML, indicating CK as an adverse risk marker for childhood AML. Typical CK-AML tended to correlate with decreased OS compared to atypical CK-AML. Moreover, CK-AML with five or more cytogenetic aberrations was associated with inferior survivals than CK with four or fewer abnormalities, suggesting that the number of cytogenetic abnormalities in CK may influence outcome. Results from our study would inform refinement of risk stratification for childhood AML to improve outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data and materials are included in this publication.

Abbreviations

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- EFS:

-

Event-free survival

- CK:

-

Complex karyotype

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- DAE:

-

Daunorubicin/cytarabine/etoposide

- abn:

-

Abnormality

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Rasche M, Zimmermann M, Borschel L, Bourquin JP, Dworzak M, Klingebiel T, et al. Successes and challenges in the treatment of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a retrospective analysis of the AML-BFM trials from 1987 to 2012. Leukemia. 2018;32(10):2167–77.

Pession A, Masetti R, Rizzari C, Putti MC, Casale F, Fagioli F, et al. Results of the AIEOP AML 2002/01 multicenter prospective trial for the treatment of children with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122(2):170–8.

Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–47.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–405.

Grimwade D, Walker H, Harrison G, Oliver F, Chatters S, Harrison CJ, et al. The predictive value of hierarchical cytogenetic classification in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): analysis of 1065 patients entered into the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML11 trial. Blood. 2001;98(5):1312–20.

Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96(13):4075–83.

Cancer, Leukemia Group B, Farag SS, Archer KJ, Mrozek K, Ruppert AS, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetics add to other prognostic factors predicting complete remission and long-term outcome in patients 60 years of age or older with acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. Blood. 2006;108(1):63–73.

Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Kayser S, Morhardt M, Benner A, Dohner K, et al. Cytogenetics and age are major determinants of outcome in intensively treated acute myeloid leukemia patients older than 60 years: results from AMLSG trial AML HD98-B. Blood. 2006;108(10):3280–8.

Creutzig U, Kutny MA, Barr R, Schlenk RF, Ribeiro RC. Acute myelogenous leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(9):e27089.

Mrozek K, Heerema NA, Bloomfield CD. Cytogenetics in acute leukemia. Blood Rev. 2004;18(2):115–36.

Dastugue N, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Pages MP, Radford I, Bastard C, Talmant P, et al. Cytogenetic profile of childhood and adult megakaryoblastic leukemia (M7): a study of the Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique (GFCH). Blood. 2002;100(2):618–26.

Manola KN, Panitsas F, Polychronopoulou S, Daraki A, Karakosta M, Stavropoulou C, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities and monosomal karyotypes in children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia: correlations with clinical characteristics and outcome. Cancer Genet. 2013;206(3):63–72.

Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley K, Harrison C, Harrison G, et al. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children’s Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood. 1998;92(7):2322–33.

Rubnitz JE, Lensing S, Razzouk BI, Pounds S, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC. Effect of race on outcome of white and black children with acute myeloid leukemia: the St Jude experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(1):10–5.

Sierra M, Alonso A, Odero MD, Gonzalez MB, Lahortiga I, Perez JJ, et al. Geographic differences in the incidence of cytogenetic abnormalities of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) in Spain. Leuk Res. 2006;30(8):943–8.

So CC, Wan TS, Chow JL, Hui KC, Choi WW, Lam CC, et al. A single-center cytogenetic study of 629 Chinese patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia–evidence of major ethnic differences and a high prevalence of acute promyelocytic leukemia in Chinese patients. Cancer Genet. 2011;204(8):430–8.

Zhang M, Yin J, He Q, Zhang F, Huang H, Wu B, et al. Chinese and Europeans with acute myeloid leukemia have discordant mutation topographies. Leuk Res. 2018;70:8–12.

Bager N, Juul-Dam KL, Sandahl JD, Abrahamsson J, Beverloo B, de Bont E, et al. Complex and monosomal karyotype are distinct cytogenetic entities with an adverse prognostic impact in paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia. A NOPHO-DBH-AML study. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(4):618–28.

Mrozek K, Eisfeld AK, Kohlschmidt J, Carroll AJ, Walker CJ, Nicolet D, et al. Complex karyotype in de novo acute myeloid leukemia: typical and atypical subtypes differ molecularly and clinically. Leukemia. 2019;33(7):1620–34.

Rasche M, von Neuhoff C, Dworzak M, Bourquin JP, Bradtke J, Gohring G, et al. Genotype-outcome correlations in pediatric AML: the impact of a monosomal karyotype in trial AML-BFM 2004. Leukemia. 2017;31(12):2807–14.

Gu R-J, Lv S-G, Sun G-X, Lu X-T, Fu R-Y, Jia C-S, et al. Childhood acute myeloid leukemia diagnosis and therapy recommendations. Chin J Pediatric. 2006;44(11):877–9.

The AGT cytogenetics laboratory manual. Fourth edition ed: Wiley Blackwell; 2017.

Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, Walker H, Chatters S, Goldstone AH, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood. 2010;116(3):354–65.

Stolzel F, Mohr B, Kramer M, Oelschlagel U, Bochtler T, Berdel WE, et al. Karyotype complexity and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e386.

An International System for Huam Cytogenomic Nomenclature (2016): Karger; 2016.

Vujkovic M, Attiyeh EF, Ries RE, Goodman EK, Ding Y, Kavcic M, et al. Genomic architecture and treatment outcome in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group report. Blood. 2017;129(23):3051–8.

Stirewalt DL, Kopecky KJ, Meshinchi S, Engel JH, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Linsley J, et al. Size of FLT3 internal tandem duplication has prognostic significance in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107(9):3724–6.

Ahmad F, Mandava S, Das BR. Mutations of NPM1 gene in de novo acute myeloid leukaemia: determination of incidence, distribution pattern and identification of two novel mutations in Indian population. Hematol Oncol. 2009;27(2):90–7.

Brown P, McIntyre E, Rau R, Meshinchi S, Lacayo N, Dahl G, et al. The incidence and clinical significance of nucleophosmin mutations in childhood AML. Blood. 2007;110(3):979–85.

Eisfeld AK, Kohlschmidt J, Schwind S, Nicolet D, Blachly JS, Orwick S, et al. Mutations in the CCND1 and CCND2 genes are frequent events in adult patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22) acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1278–85.

Micol JB, Duployez N, Boissel N, Petit A, Geffroy S, Nibourel O, et al. Frequent ASXL2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1 chromosomal translocations. Blood. 2014;124(9):1445–9.

Pan L, Li Y, Zhang HY, Zheng Y, Liu XL, Hu Z, et al. DHX15 is associated with poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and regulates cell apoptosis via the NF-kB signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(52):89643–54.

Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–9.

Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–4.

Li X, Li X, Xie W, Hu Y, Li J, Du W, et al. Comprehensive profile of cytogenetics in 2308 Chinese children and adults with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2012;49(2):107–13.

Lee NH, Choi YB, Yi ES, Lee SH, Kim HJ, Lee JW, et al. Monosomal karyotype is not a predictor of dismal outcome in childhood de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2016;50:57–62.

Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, Rasche M, von Neuhoff C, Alpermann T, et al. Changes in cytogenetics and molecular genetics in acute myeloid leukemia from childhood to adult age groups. Cancer. 2016;122(24):3821–30.

Stark B, Jeison M, Gabay LG, Mardoukh J, Luria D, Bar-Am I, et al. Classical and molecular cytogenetic abnormalities and outcome of childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: report from a referral centre in Israel. Br J Haematol. 2004;126(3):320–37.

Betts DR, Ammann RA, Hirt A, Hengartner H, Beck-Popovic M, Kuhne T, et al. The prognostic significance of cytogenetic aberrations in childhood acute myeloid leukaemia. A study of the Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group (SPOG). Eur J Haematol. 2007;78(6):468–76.

Schoch C, Kern W, Kohlmann A, Hiddemann W, Schnittger S, Haferlach T. Acute myeloid leukemia with a complex aberrant karyotype is a distinct biological entity characterized by genomic imbalances and a specific gene expression profile. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;43(3):227–38.

Masetti R, Castelli I, Astolfi A, Bertuccio SN, Indio V, Togni M, et al. Genomic complexity and dynamics of clonal evolution in childhood acute myeloid leukemia studied with whole-exome sequencing. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56746–57.

Farrar JE, Schuback HL, Ries RE, Wai D, Hampton OA, Trevino LR, et al. Genomic Profiling of Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia Reveals a Changing Mutational Landscape from Disease Diagnosis to Relapse. Cancer Res. 2016;76(8):2197–205.

Mrozek K. Cytogenetic, molecular genetic, and clinical characteristics of acute myeloid leukemia with a complex karyotype. Semin Oncol. 2008;35(4):365–77.

Hollink IH, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Zimmermann M, Balgobind BV, Arentsen-Peters ST, Alders M, et al. Clinical relevance of Wilms tumor 1 gene mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(23):5951–60.

Hou HA, Huang TC, Lin LI, Liu CY, Chen CY, Chou WC, et al. WT1 mutation in 470 adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: stability during disease evolution and implication of its incorporation into a survival scoring system. Blood. 2010;115(25):5222–31.

Rucker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, Kayser S, Teleanu V, Kett H, et al. TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood. 2012;119(9):2114–21.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the patients, families, and physicians for their participation in the study.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81802092); Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (No. cstc2018jcyjAX0326).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB and JY developed concept and design. XC, XW, HD, ZY, JB and LB conducted data collection and assembly. LB, JY, XC, XW, YH and LL performed data analysis and interpretation. XC, XW and LB prepared manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. List of complex karyotypes

Additional file 2

. Comparison of clinical and molecular features of childhood CK-AML with typical and atypical CK

Additional file 3

. Comparison of clinical and molecular features of childhood CK-AML with ≤4 or ≥5 cytogenetic aberrations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Wang, X., Dou, H. et al. Cytogenetic and mutational analysis and outcome assessment of a cohort of 284 children with de novo acute myeloid leukemia reveal complex karyotype as an adverse risk factor for inferior survival. Mol Cytogenet 14, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-021-00547-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-021-00547-0