Abstract

Background

Diffuse astrocytomas are characterized by their highly variable biological behavior. The possibility that tumors develop novel aberrations, with relevant biological properties, is often neglected. In this study, we present two cases of diffuse astrocytoma in which additional cytogenetic and epigenetic markers with potential influence on cell proliferation or differentiation were detected at relapse.

Findings

The biopsies taken from the primary and recurrent tumors of two patients were analyzed with molecular methods to detect copy number variations (CNVs), gene mutations and epigenetic changes. Both cases were characterized by the R132H mutation in the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) gene. Features typical of astrocytomas, such as copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity at 17p and the deletion of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) gene, were also detected in both cases. These markers were present in the primary and recurrent lesions. Other aberrations, predominantly deletions or amplifications of chromosomal segments and the hypermethylation of gene promoters, were detected in the recurrent lesions.

Conclusions

The IDH1 mutation was the primary event, as previously reported. According to our observations, the methylation of promoters constituted later events, which may have further disrupted cell proliferation and/or differentiation, together with additional CNVs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

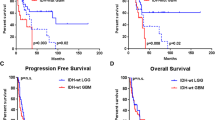

Diffuse astrocytomas constitute one of the major subtypes of glial tumors, with highly variable biological behavior. In recent years, several genetic markers have been identified that predict the responses to defined therapeutic strategies, and can therefore affect the outcomes of individual patients. One example is the presence of an IDH1 gene mutation, which confers a better overall prognosis and longer progression-free survival on patients with grade II–III astrocytoma, irrespective of treatment [1, 2]. The methylation status of the O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter plays a similar role in the choice of therapy [3].

The majority of recurrent gliomas are characterized by a shared set of mutated genes and chromosomal aberrations, which probably derive from the same precursor cell [4, 5]. Therefore, many clinicians therapeutically target the molecular markers defined in the initial tumor. However, recurrent lesions appear after an asymptomatic period in the majority of patients, despite defined multidrug chemotherapy and radical surgical resection. The possibility that the tumor develops novel aberrations, with relevant biological properties, is often neglected.

In this study, we report two cases of diffuse astrocytoma in which additional cytogenetic and epigenetic markers, with potential effects on cell proliferation or differentiation, were detected at the time of relapse.

Methods

Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (I-FISH)

Dual-color I-FISH with LSI and/or CEP DNA probes (Abbott Vysis, Chicago, IL) was used to analyze copy number variations (CNVs) in the CDKN2A (9p21.3), EGFR (7p12), PTEN (10q23.3), RB1 (13q14.2) and TP53 (17p13.1) genes, in 1p and 19q regions. I-FISH was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The cut-off values were established in previous studies as 5 % for deletions and 2.5 % for amplifications [6].

DNA isolation

The homogenized tumor tissues were used to isolate the genomic DNA (gDNA) with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc., Germantown, MD), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. gDNA obtained from peripheral blood was isolated by GenElute Blood Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

SNP array

The gDNA (200 ng) was hybridized onto the HumanCytoSNP-12 (v2.1) BeadChip array (Illumina, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The array was scanned with a BeadArray Reader (Illumina) and the scan was analyzed with the BlueFuse Multi software v4.1 (Illumina). The detection limit of the SNP arrays was 15 % of cell clones.

MLPA

Mutations in the IDH1/IDH2 genes were detected with the P370 BRAF-IDH1-IDH2 probemix (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The promoter methylation of MGMT and six mismatch repair genes was investigated with the methylation-specific MLPA (MS-MLPA) using ME011 Mismatch Repair genes probemix (MRC-Holland). Both MLPA analyses were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

MS-PCR

MS-PCR was performed according previously published protocol [7]. Bisulfide conversion was performed with the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold™ Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). The products of PCR were separated on 2 % agarose gel stained with SERVA DNA Stain Clear G (SERVA Electrophoresis GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany).

Results

Both patients were diagnosed with astrocytoma and treated at the Department of Neurosurgery, Central Military Hospital and 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic. The patients gave their written consent for the use of their biological material for research purposes. The tumor tissues were taken during routine neurosurgical procedures and peripheral blood was used as the negative control. All resections were characterized by I-FISH, SNP array, MLPA and MS-PCR.

Case no. 1 was a male patient who was diagnosed with gemistocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade II) at the age of 31 years. Six years later, a second radical resection (no tumor remnant was detected) was performed and the tumor was determined to be a diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II). A third resection (anaplastic astrocytoma WHO grade III) was performed 5 months later (Fig. 1). The tumor was localized in the left frontal lobe. The patient is currently undergoing treatment with chemotherapy and his survival is 101 months.

Mutation R132H in the IDH1 gene was detected in all resections. The first resection was characterized by deletions, amplifications and CN-LOH on chromosomes 3, 7p, 9q, 12q, 13q and 19q (Fig. 2, Table 1). The changes in 13q and 19q were verified with I-FISH. No hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter or any other promoter analyzed was detected (average ratio ≥ 25 %) [8]. The second resection included the same CNVs as the first, with additional changes on 10p, 13q and 19p. The hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter was confirmed in this resection. Additional deletions at 8q11.1q22.3 and 10q22.3q23.1, and trisomy of chromosome 7 (7 % of cells), detected only with I-FISH, were found in the third resection.

Molecular cytogenetic and epigenetic analyses of the three lesions of case no. 1. a Results of a SNP array for each lesion, with the selection of three chromosomes, in which additional changes were detected. Red bars indicate deletions of a chromosomal region. Green bars represent amplifications, and CN-LOH is marked with gray boxes. b Result of I-FISH analysis confirming and extending the SNP array findings. 1,3, deletion of 19q13 probe; 2, amplification of 13q34; 4, multiple amplifications of 13q34 probe; 5, amplification of 13q34 with monoallelic loss of the RB1 gene; and 6, trisomy of chromosome 7

Case no. 2 was a female patient diagnosed with recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III) at the age of 36 years. The second resection (anaplastic astrocytoma, WHO grade III) was performed 10 months later (Fig. 3). The tumor was localized in left parietal lobe. The patient was treated with chemotherapy, but died 1 year after the second resection from further tumor progression. Patient´s survival was 87 months.

Both resections were characterized by the R132H mutation in the IDH1 gene, CNVs including chromosomes X, 5, 6, 16, 17 and 22 and chromosomal arms 4q, 7q, 9p, 10q, 11p, 13q, 14q, 18q and 19p (Fig. 4, Table 2). A chromothripsis was also detected on chromosome arm 13q. The first specimen had several unique features: CN-LOH on chromosomes 2, 3p, 12q, and 21 and deletion of 15q. The second resection was defined by CN-LOH on 1q and 2q, and the hypermethylation of the MLH3 and MGMT promoters. Methylation of MHL3 promoter was verified by MS-PCR (Fig. 5). I-FISH analyses verified the deletion of CDKN2A, PTEN and 6q.

Molecular cytogenetic and epigenetic analyses of the three lesions of case no. 2. a Results of the SNP array for each lesion, with the selection of three chromosomes, in which the additional changes were detected. Red bars indicate the deletion of a chromosomal region. Green bars represent amplifications, and CN-LOH is marked with gray boxes. b Results of I-FISH analysis confirming and extending the SNP array findings. 1, biallelic deletion of subtelomeric area of the long arm of chromosome 6; 2, biallelic deletion of the CDKN2A gene; 3, deletion of the PTEN gene in polyploid nuclei; 4, the RB1 gene and 13q34 were not affected by chromothripsis

Discussion

Gliomas represent typical examples of multistep oncogenesis, in which new mutations are acquired under clonal selection, and the tumor can thus evolve to a more aggressive form [9]. Both our cases were characterized by a set of CNVs that was present in all the samples acquired for each patient, even after the radical resection of the previous lesion (Figs. 2, 4 and Tables 1, 2). However, whereas case no. 1 showed the typical acquisition of genetic and epigenetic aberrations in each step of the evolution of his astrocytoma, case no. 2 was characterized by different additional changes in each resection. These findings support the theory of the monoclonal origin of astrocytomas, and also suggest that a specific set of genetic features, typical for each patient, are necessary to maintain the glial cells in the tumor state [9, 10].

The IDH1 gene was mutated in both primary lesions. The mutated form of the IDH1 gene leads to the epigenetic deregulation described as the ‘glioma CpG island methylator phenotype’ [11]. Therefore, the MGMT hypermethylation observed in both cases and the methylation of the MLH3 promoter in case no. 2 might result from the mutated IDH1 gene. The methylation of both promoters always occurred as a secondary event in the recurrent lesion, so our finding supports the hypothesis that IDH1 mutation is the primary event in glioma carcinogenesis [12]. The methylation of the MLH3 promoter is a new finding, and is reported to appear in 27 % of astrocytomas [7], although its role in glioma is yet to be investigated.

Chromothripsis was recently described in gliomas with IDH1 gene mutation. Although no prognostic significance was observed in that study [13], it is generally believed that chromothripsis contributes to tumorigenesis. We observed chromothripsis on 13q in the astrocytoma of patient no. 2, who died after the third resection from tumor progression. Whether chromothripsis was one of the triggers of tumor progression remains to be clarified.

Progression towards a higher WHO grade occurred between the second and third resection in case no. 1. The additional aberrations that occurred between these lesions were deletions at 8q11.1q22.3, which contains 166 OMIM genes, and at 10q22.3q23.1 where 13 genes are localized. Two of these genes are neuregulin 3 (NRG3, 10q23.1), which encodes an oligodendrocyte survival factor [14], and nibrin (NBN, 8q21.3), which encodes a protein crucial for maintaining genomic stability by affecting the DNA damage signaling pathway [15]. Therefore, the deletion of these genes might influence the tumorigenic potential of astrocytoma.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that each of investigated astrocytomas share a set of CNVs and epigenetic modifications that are necessary for maintaining the malignant status of glial cells during tumor evolution. However, new genetic or epigenetic markers, such as deletions on 8q,10q or the methylation of the MLH3 promoter, may occur in response to clonal selection. The emergence of new aberrations, caused by treatment or of random gains that improve clonal proliferation may also influence the patient’s response to treatment. MutS homolog 6 (MSH6) may be one such example. Its mutation is induced by temozolomide treatment and causes drug resistance in the affected glioblastomas [16].

Therefore, each tumor recurrence must be genetically and epigenetically characterized to allow the correct therapeutic decision to be made. The methylation of the MLH3 promoter, the deletion of the NGR3 and NBN genes or chromothripsis on 13q observed in our study are potential phenomena that might influence tumor cell behavior and thus modulate the tumor’s responsiveness to treatment.

References

Wick W, Hartmann C, Engel C, Stoffels M, Felsberg J, Stockhammer F, et al. NOA-04 randomized phase III trial of sequential radiochemotherapy of anaplastic glioma with procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine or temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5874–80.

Hartmann C, Meyer J, Balss J, Capper D, Mueller W, Christians A, et al. Type and frequency of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are related to astrocytic and oligodendroglial differentiation and age: a study of 1,010 diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:469–74.

Dong X, Liu RY, Chen WD. Correlation of promoter methylation in the MGMT gene with glioma risk and prognosis: a meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2014. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8760-3.

Lass U, Numann A, von Eckardstein K, Kiwit J, Stockhammer F, Horaczek JA, et al. Clonal analysis in recurrent astrocytic, oligoastrocytic and oligodendroglial tumors implicates IDH1- mutation as common tumor initiating event. Plos One. 2012;7:14.

Suzuki H, Aoki K, Chiba K, Sato Y, Shiozawa Y, Shiraishi Y, et al. Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):458–68.

Zemanova Z, Kramar F, Babicka L, Ransdorfova S, Melichercikova J, Hrabal P, et al. Molecular cytogenetic stratification of recurrent oligodendrogliomas: Utility of interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (I-FISH). Folia Biol. 2006;52:71–8.

Lhotska H, Zemanova Z, Cechova H, Ransdorfova S, Lizcova L, Kramar F, et al. Genetic and epigenetic characterization of low-grade gliomas reveals frequent methylation of the MLH3 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2015;54(11):655–67.

Jeuken JW, Cornelissen SJB, Vriezen M, Dekkers MMG, Errami A, Sijben A, et al. MS-MLPA: an attractive alternative laboratory assay for robust, reliable, and semiquantitative detection of MGMT promoter hypermethylation in gliomas. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1055–65.

Kattar MM, Kupsky WJ, Shimoyama RK, Vo TD, Olson MW, Bargar GR, et al. Clonal analysis of gliomas. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1166–79.

Payton JE, Schmidt J, Yu J, Lusis EA, Watson MA, Gutmann DH. Genome-wide polymorphism analysis demonstrates a monoclonal origin of pilocytic astrocytoma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37:321–5.

Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP, et al. Identification of a CpG Island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of Glioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:510–22.

Watanabe T, Nobusawa S, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations are early events in the development of astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1149–53.

Cohen A, Sato M, Aldape K, Mason CC, Alfaro-Munoz K, Heathcock L, et al. DNA copy number analysis of Grade II-III and Grade IV gliomas reveals differences in molecular ontogeny including chromothripsis associated with IDH mutation status. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:34.

Carteron C, Ferrer-Montiel A, Cabedo H. Characterization of a neural-specific splicing form of the human neuregulin 3 gene involved in oligodendrocyte survival. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:898–909.

Hou YY, Toh MT, Wang X. NBS1 deficiency promotes genome instability by affecting DNA damage signaling pathway and impairing telomere integrity. Cell Biochem Funct. 2012;30:233–42.

Yip S, Miao JY, Cahill DP, Iafrate AJ, Aldape K, Nutt CL, et al. MSH6 mutations arise in glioblastomas during temozolomide therapy and mediate temozolomide resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4622–9.

Shaffer LG, McGowan-Jordan J, Schmid M. ISCN 2013: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Karger: Basel; 2013.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (NT/13212-4).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Authors have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to the Molecular Cytogenetics.

Authors’ contributions

HL: isolated gDNA, performed and analyzed the SNP array experiments, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; ZZ: provided the conception of the study and revised the manuscript; HC: performed the MLPA and MS-MLPA experiments; SR: performed and analyzed I-FISH; KS: isolated gDNA and analyzed I-FISH; FK: performed neurosurgical procedures and provided patients data; ZK: performed the SNP array experiments; KM: provided contribution to the conception of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lhotska, H., Zemanova, Z., Cechova, H. et al. Primary and recurrent diffuse astrocytomas: genomic profile comparison reveals acquisition of biologically relevant aberrations. Mol Cytogenet 9, 13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-016-0222-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-016-0222-3