Abstract

Background

Proximal deletions in the 13q12.11 region are very rare. Much larger deletions including this region have been described and are associated with complex phenotypes of mental retardation, developmental delay and various others anomalies.

Results

We report on a 3-year-old girl with a rare 2.9 Mb interstitial deletion at 13q12.11 due to a de novo unbalanced t(13;14) translocation. She had mild mental retardation and relatively mild dysmorphic features such as microcephaly, flat nasal bridge, moderate micrognathia and clinodactyly of 5th finger. Molecular karyotyping revealed a deletion on the long arm of chromosome 13 as involving sub-bands 13q12.11, a deletion of about 2.9 Mb.

Discussion

The clinical application of array-CGH has made it possible to detect submicroscopical genomic rearrangements that are associated with varying phenotypes.The description of more patients with deletions of the 13q12.11 region will allow a more precise genotype-phenotype correlation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Genetic testing, such as chromosome analysis, is an important diagnostic tool for patients with unexplained developmental delay, dysmorphisms and other developmental disabilities. The development of novel high-resolution molecular methods such as array based comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH) increased the resolution of chromosomal studies enabling the detection of submicroscopic chromosome aberrations, otherwise not detectable by conventional cytogenetic techniques [1].

Herein, we report the case of a 5 ½ years old female child with developmental delay and a relatively mild phenotype. The karyotype revealed a de novo translocation between chromosomes 13 and 14. Further analysis using array-CGH, however, revealed a 2.9 MB deletion within the 13q12.11 region. To date, two similar cases have been reported with an interstitial deletion within the 13q12.11 region presenting similar phenotypic characteristics and overall development and intellect [2],[3].

Case presentation

Case report

The patient was a female child born to unrelated healthy young parents after an uncomplicated 36 weeks pregnancy. She was referred to our unit for developmental assessment at the age of 3 years and 2 months because of speech and language delay.

Delivery was by cesarean section because of premature rupture of membranes. Birth weight was 3,150 kg (50th percentile), length was 47 cm (10th percentile) and head circumference (H.C.) was 32 cm (3rd percentile). At birth she presented with incomplete soft cleft palate which was surgically corrected at the age of 14 months (Figure 1a). Her motor milestones were delayed as she sat independently at the age of 10 months and walked unaided at the age of 19 months. Her language development was also delayed as first words appeared after the age of 2 years.

Views of the patient at the age of 5 years and 5 months. (a) Frontal view of the face of the patient. Incomplete soft cleft palate surgically corrected at the age of 14 months. (b) Dorsal view of the hand of the patient showing clinodactyly of 5th finger. (c) Frontal view of the patient showing the widely spaced nipples.

Physical examination revealed a sociable child, with mild dysmorphic facial and body features such as microcephaly, small eyes with epicanthal folds, flat nasal bridge, moderate micrognathia and clinodactyly of 5th finger. Her weight was 12 kg (10-25th percentile), height 86 cm (3-10th percentile) and head circumference 46 cm (< 2nd percentile).

On developmental examination she showed good social and communication skills but with poor cognitive and verbal abilities. Her vocabulary consisted of around 20 simple words and two to three “2-word phrases”. According to Bayley Scales of Infant Development [4], her mental IQ score was 68.

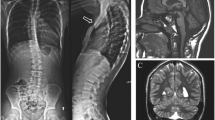

Neurological examination revealed central generalized hypotonia without asymmetries or focal signs. Brain MRI scan showed mild dilation of the subarachnoid space. Audiological examination showed conductive hearing impairment and short external acoustic canal. Visual assessment revealed hypermetropic astigmatism. Biochemical tests, bone age, extensive metabolic investigation (including plasma aminogram, urine mucopolysaccharides, organic acids and lysosomal enzymes) and kidney-liver-spleen ultrasound proved normal.

She was re-evaluated at the age of 5 years and 5 months. She attended mainstream kindergarten and received speech therapy twice a week on regular basis. She remained sociable with mild microcephaly (HC = 48 cm, 3rd percentile) and the same mild dysmorphic features (small eyes with marked epicanthus, moderate micrognathia, widely spaced nipples and clinodactyly of 5th finger) (Figures 1b and c). Her speech was delayed consisting of small phrases with morphological and phonological disturbances. Her overall development was equivalent to a 4 year-old level with mental IQ score = 74. Her weight was 18 kg (25th percentile) and her height 105 cm (3rd percentile). Her hypermetropic astigmatism was corrected with glasses. Biochemical and endocrinological re-evaluation proved normal.

Methods and results

Blood chromosome analysis was performed in the patient and her parents using high-resolution banding techniques. Twenty metaphases were analyzed from each subject by GTG- banding.

Molecular karyotyping was carried out on the DNA extracted from whole blood of the patient and both her parents according to standard procedures. All the experiments were conducted through oligonucleotide array-CGH platforms (SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray, 4x180K, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Briefly, 500 ng of proband DNA and of a sex–matched reference DNA (NA10851, Coriell Cell Repositories) were processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence was scanned in a dual-laser scanner (DNA Microarray Scanner with Sure Scan High-Resolution Technology, Model G2565CA, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and the images were extracted and analyzed through Agilent Feature Extraction Software (v10.5.1.1). Graphical overview was obtained using the Genomic Workbench (v6.5) software. Changes in test DNA copy number at a specific locus were observed as the deviation of the log2 ratio value of 0 of at least three consecutive probes. The quality of each experiment was assessed by using a parameter provided by Agilent software (QC metric) and on the basis of DNA quality. Copy number changes identified in the samples were evaluated by using the UCSC Genome Browser website (http://genome.ucsc.edu) and the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation). The positions of oligomers refer to the Human Genome February 2009 (versions NCBI 37, hg19) assembly. The DECIPHER (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/application) database was used to support genotype-phenotype correlation.

The array-CGH results were confirmed by copy number profiling using a qPCR method as previously described [5]. Two genes which map, the first at the beginning (GJA3 gap junction, alpha 3 = 20.712,394-20,735,188) and the second at the end (LINC00540 long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 540 = 22,681,609-22,850,660) of the putatively deleted region, were amplified with specific primers using the LightCycler® FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I mix (Roche Applied Science, Roche Diagnostics S.p.A., Monza, Italy). The real-time reactions were analyzed on a LightCycler® 1.5 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The concentration of the DNA samples was adjusted by including two reference genes, EIF3L and KDELR3, that are located on chromosome 22. Relative quantification, in respect to a calibration curve used to establish efficiency, was utilized to detect the number of copies of DNA targets per diploid genome. All PCR experiments were replicated three times. qPCR results demonstrated the presence of a single copy of the two target genes, per diploid genome of the fetus, confirming the array-CGH data (data not shown).

Cytogenetic analysis of the patient revealed a balanced translocation between acrocentric chromosomes 13 and 14. Chromosomal analysis of her parents showed normal karyotype and determined that the abnormality was de novo. The karyotype according to ISCN was 46,XX,der(13;14)(q12.11;qter)dn (Figure 2). Further genetic investigation was performed with the use of array-CGH. Molecular karyotyping revealed a deletion on the long arm of chromosome 13 as involving sub-bands 13q12.11, a deletion of about 2.9 Mb (chr13: 19938561–22840254) (Figure 3). A benign copy number variation (CNV) duplication in cytoband 15q11.2 (chr15:20602842–22509395) was also observed. This CNV contains 1.9 Mb of genomic material and includes genes BCL8 and POTEB. In the Genomic Data of Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/), this kind of CNV is described as a genetic polymorphism often seen in healthy individuals, and therefore is not expected to be linked to any pathologic phenotype.

Discussion

Proximal deletions in the 13q12.11 region are very rare. Much larger deletions including this region have been described and are associated with complex phenotypes of mental retardation, developmental delay and various others anomalies.

We describe a 5 ½ years old girl presenting with developmental delay, microcephaly, small eyes with marked epicanthus, flat nasal bridge, moderate micrognathia, strabismus, broad nasal bridge, widely spaced nipples, posteriorly rotated ears, and clinodactyly of the 5th finger.

To date, two other cases with interstitial deletion within the 13q12.11 region have been reported and presented similar developmental and facial characteristics (Table 1) [2],[3]. Kaloustian et al. [2] reported a patient with mild developmental delay, craniofacial dysmorphism, pectus excavatum, narrow shoulders, malformed toes, and café-au-lait spots. Array- CGH analysis revealed a de novo deletion spanning 2.1 Mb within cytogenetic band 13q12.11. The deleted region encompassed 16 genes. The second case, a patient with a 2.9 Mb deletion, was reported by Tanteles et al. [3]. It was a 16-year-old boy with a degree of facial dysmorphism, scaphocephaly, torticollis and near normal development and intellect. The deletion produced hemizygoxity for 19 known genes.

According to the DECIPHER database six cases are mentioned in the area of our interest, within the area of 20,797,139 to 21,099,089, (cases: 1032, 261403, 273408, 285395, 288952, 289764) with micro deletions ranging from 180 kb to 290 kb, presenting major figures such us intellectual disability, delayed speech and language development and according to the NCBI RNA Reference Sequences Collection (RefSeq), the deleted area of our patient encompasses 20 transcribed genes and (Figure 4). Four of these genes GJA3, GJB2, GJB6, and FGF9 are known to be associated with monogenic disorders and have potential clinical significance. GJA3 causes autosomal dominant zonular pulverulent cataract-3 [6] while GJB2 and GJB6 genes cause autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing loss worldwide [7]–[9]. In addition, autosomal dominant mutations in GJB2 are responsible for Keratitis-Ichthyosis-Deafness syndrome and rare forms of palmoplantar keratoderma associated with sensorineural hearing loss [10]–[12]. Mutations in GJB6 may also cause a form of hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia known as Clouston syndrome [13]. Our patient did not show signs of sensorineural hearing loss nor Clouston syndrome. A mechanism for an autosomal recessive disorder could be a large deletion on the one chromosome and a point mutation on the other chromosome.

Schematic representation of our patient’s deletion showing 2.9 Mb from chromosome 13 (chr13), positions 19,938,561-22,840,254 according to Database of Genomic Variants genome browser image Build GRCh37: Feb. 2009, hg 19. The deleted area of the two other patients and the genes involved are also noted.

Other known transcribed genes in the deleted region are the FGF9, LATS2 and IFT88 genes. FGF9 is associated with one form of multiple synostoses syndrome [14] while loss of heterozygosity at the LATS2 gene is associated with non-small cell lung cancer [15]. IFT88 is considered a candidate gene for renal disease [16]. These three disorders are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, but it is possible that haploinsufficiency due to deletion on the one chromosome is not a causative mechanism for these particular disorders.

Conclusion

Comparison of the extent of the reported deletions and the phenotype of the patients indicates that our patient with a 2.9 Mb 13q12.11 deletion does not represent a shortest region of overlap (SRO) of a microdeletion syndrome. The deletion appears, however, associated with a number of abnormalities such as mild developmental delay, speech problems, microcephaly, and mild dysmorphic features. The description of more patients with deletions of the 13q12.11 region will allow a more precise genotype-phenotype correlation.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of this patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- array-CGH:

-

Array based comparative genomic hybridization

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- CNV:

-

Copy number variation

- ISCN:

-

International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature

- SRO:

-

Shortest region of overlap

References

Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, Biesecker LG, Brothman AR, Carter NP, Church DM, Crolla JA, Eichler EE, Epstein CJ, Faucett WA, Feuk L, Friedman JM, Hamosh A, Jackson L, Kaminsky EB, Kok K, Krantz ID, Kuhn RM, Lee C, Ostell JM, Rosenberg C, Scherer SW, Spinner NB, Stavropoulos DJ, Tepperberg JH, Thorland EC, Vermeesch JR, Waggoner DJ, Watson MS, et al.: Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet 2010, 86: 749–764. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006

Der Kaloustian VM, Russell L, Aradhya S, Richard G, Rosenblatt B, Melançon S: A de novo 2.1-Mb deletion of 13q12.11 in a child with developmental delay and minor dysmorphic features. Am J Med Genet A 2011, Part A 155: 2538–2542. 10.1002/ajmg.a.34198

Tanteles GA, Dixit A, Smith N, Martin K, Suri M: Mild phenotype in a patient with a de-novo 2.9-Mb interstitial deletion at 13q12.11. Clin Dysmorphol 2011, 20: 61–65. 10.1097/MCD.0b013e328346f6dc

Baley N: Scales of infant Development. 2nd edition. San Antonio Psychological Corporation; 1993.

D’haene B, J Vandesompele J, Hellemans J: Accurate and objective copy number profiling using real-time quantitative PCR. Methods 2010, 50: 262–270. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.12.007

Mackay D, Ionides A, Kibar Z, Rouleau G, Berry V, Moore A, Shiels A, Bhattacharaya S: Connexin 46 mutations in autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Am J Hum Genet 1999, 64: 1357–1364. 10.1086/302383

Denoyelle F, Marlin S, Weil D, Moatti L, Chauvin P, Garabedian EN, Petit C: Clinical features of the prevalent form of childhood deafness, DFNB1, due to a connexin-26 gene defect: implications for genetic counselling. Lancet 1999, 353: 1298–1303. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11071-1

Grifa A, Wagner CA, D’Ambrosio L, Melchionda S, Bernardi F, Lopez-Bigas N, Rabionet R, Arbones M, Della Monica M, Estivill X, Zelante L, Lang F, Gasparini P: Mutations in GJB6 cause nonsyndromic autosomal dominant deafness atDFNA3locus. Nat Genet 1999, 23: 16–18.

del Castillo L, Villamar M, Moerno-Pelayo MA, del Castillo FJ, Alvarez A, Telleria D, Men_endez I, Moreno F: A deletion involving the connexion 30 gene in nonsyndromic hearing impairment. N Engl J Med 2002, 346: 243–249. 10.1056/NEJMoa012052

Richard G, White TW, Smith LE, Bailey RA, Campton JG, Paul DL, Bale SJ: Functional defects of Cx26 resulting from a heterozygous missense mutation in a family with dominant deaf-mutism and palmoplantar keratoderma. Hum Genet 1998, 103: 393–399. 10.1007/s004390050839

Maestrini E, Korge BP, Ocana-Sierra J, Calzolari E, Cambiaghi S, Scudder PM, Hovnanian A, Monaco AP, Munro CS: A missense mutation in connexin 26, D66H, causes mutilating keratoderma with sensorineural deafness (Vohwinkel’s syndrome) in three unrelated families. Hum Mol Genet 1999, 8: 1237–1243. 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1237

Heathcote K, Syrris P, Carter ND, Patton MA: A connexin 26 mutation causes a syndrome of sensorineural hearing loss and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (MIM 148350). J Med Genet 2000, 37: 50–55. 10.1136/jmg.37.1.50

Lamartine J, Essenfelder GM, Kibar Z, Lanneluc I, Callouet E, Laoudj D, Lemaıtre G, Hand C, Hayflick SJ, Zonana J, Antonarakis S, Radhakrishna U, Kelsell DP, Christianson AL, Pitaval A, Der Kaloustian V, Fraser C, Blanchet-Bardon C, Rouleau GA, Waksman G: Mutations in GJB6 cause hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Nat Genet 2000, 26: 142–144. 10.1038/79851

Wu X, Gu M, Huang L, Liu X, Zhang H, Ding X, Xu J, Cui B, Wang L, Lu S, Chen X, Zhang H, Huang W, Yuan W, Yang J, Gu Q, Fei J, Chen Z, Yuan Z, Wang Z: Multiple synostoses syndrome is due to a missense mutation in exon 2 of FGF9 gene. Am J Hum Genet 2009, 85: 53–63. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.007

Strazisar M, Mlakar V, Glavac D: LATS2 tumour specific mutations and down-regulation of the gene in non-small cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer 2009, 64: 257–262. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.09.011

Onuchic LF, Schrick JJ, Ma J, Hudson T, Guay-Woodford LM, Zerres K, Woychick RP, Reeders ST: Sequence analysis of the human hTg737 gene and its polymorphic site in patients with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Mamm Genome 1995, 6: 805–808. 10.1007/BF00539009

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their thanks to the members of the family of the patient for the collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ML wrote the manuscript; LT referred the patient for study; LT and MBP coordinated the clinical analysis of the patient; EM and MK performed the cytogenetic analysis; IP, EM signed out the molecular cytogenetic results; GK performed the ophthalmologic examination; VP, GD and EA performed prenatal ultrasound scan; and EM coordinated the study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lagou, M., Papoulidis, I., Orru, S. et al. A de novo 2.9 Mb interstitial deletion at 13q12.11 in a child with developmental delay accompanied by mild dysmorphic characteristics. Mol Cytogenet 7, 92 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-014-0092-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-014-0092-5