Abstract

Bakground

The operating room is a demanding and time-constrained setting, in comparison to primary care settings, where perioperative medication administration is more complicated and there is a high risk that the patient will experience a medication error. Without consulting the pharmacist or seeking assistance from other staff members, anesthesia clinicians prepare, deliver, and monitor strong anesthetic drugs. The purpose of this study was to determine the Incidence and root causes of medication errors by anesthetists in Amhara region, Ethiopia.

Methods

A multi-center cross sectional web-based survey study was conducted from October 1 to November 30, 2022, across eight referral and teaching hospitals of Amhara region. A self-administered semi structured questionnaire was distributed using survey planet. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics were computed and binary logistic regression was used for data analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 108 anesthetists in total, yielding a response rate of 42.35%. Out of 104 anesthetists, Majority of participants (82.7%) were male. During their clinical practice, more than half (64.4%) of participants experienced atleast one drug administration error. 39 (37.50%) of the respondents revealed that they experienced more medication errors while on night shifts. Anesthetists who did not always double-check their anesthetic drugs before administration had a 3.51 higher risk of developing MAEs compared to those who always double-check anesthetic drugs before administration (AOR = 3.51; 95% CI: 1.34, 9.19). Additionally, participants who administer medications that have been prepared by someone else are about five times more likely to experience MAEs than participants who prepare their own anesthetic medications prior to administration (AOR = 4.95; 95% CI: 1.54, 15.95).

Conclusion

The study found a considerable rate of errors in the administration of anaesthetic drugs. The failure to always double-check medications before administration and the use of drugs prepared by another anaesthetist were identified to be underlying root causes for drug administration errors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The operating room is a demanding and time-constrained setting, in comparison to primary care settings, where perioperative medication administration is more complicated and there is a high risk that the patient will experience a medication error [1]. Without consulting the pharmacist or seeking assistance from other staff members, anesthesia clinicians prepare, deliver, and monitor strong anesthetic drugs [2, 3]. Studies in anesthesia have shown that drug errors have been highly prevalent globally [4, 5].

The range of consequences from medication error effects runs from no notable effects to death. In some cases, it can cause a new condition, either temporary or permanent, such as itching, rashes, or skin disfigurement [6, 7]. Inadvertently prescribing the incorrect medication to a patient or having a near-miss could cause shame, guilt, and self-doubt in medical professionals. This is known as the “second victim,“ and it can have potentially fatal consequences [8]. In addition to suing the healthcare provider, patients or patients’ families may also sue the healthcare facility where the healthcare provider works for personal injury [9,10,11]. An extensive self reported survey result conducted in Canada, shown that Although most errors (1,038) were of minor consequence (98%), four deaths were reported [12]. In addition to increasing the risk of patient morbidity and even death, incorrect drug administration can increase the length of hospital stays, which has an impact on the economy.

Furthermore, Hospitals may have to pay a significant amount for legal counsel and potential settlement costs. Along with the increased cost of unplanned prolonged hospitalisation and patient care, hospitals may also be responsible for the lost productivity of the staff involved in the error [13]. Dealing with the errors, investigation, litigation, and settlement may also take some time. The management team of the hospital may have to invest time and resources to look into and change policies to reduce future mistakes [5, 14]. Aside from causing personal harm, adverse drug reactions put a heavy financial burden on healthcare systems. Therefore, successful efforts to stop medication errors will increase patient safety and result in cost savings On the other hand it is documented that one of the greatest ways offered to improve patient safety by minimizing the volume of medication administraton errors (MAEs) is to identify and intervene with the underlying root causes of MAEs [9]. One of the least studied and unaddressed health issues in developing countries like Ethiopia, which have issues with their economies, workforce, and education, is MAEs in anesthetic clinical practice. As a result, the purpose of this study was to determine the type, how frequently and what underlying root causes lead to medication errors in patients under anesthesia.

Methods

A multicenter web-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among anesthetists working at Amhara region in Ethiopia from October 1 to November 30, 2022. The study was carried out in eight teaching hospitals, including the Woldya Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the Tibebe Gion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the Debremarkos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the Debrebrhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, and the Debretabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. Because of increasing patient flow and clinical practitioners, those referral and teaching institutions were chosen to better reflect actual clinical practice.

Utilizing Survey Planet and their email and telegram addresses, 255 anesthetists employed at the specified hospitals received the questionnaires. The inclusion Criteria were all anesthetists with a minimum of six months of working experience, the ability to respond to the questioner using the listed online choices, and involved in direct patient care to be included in the study. Those anesthetists who are not involved in medication administration practice and the ones serving in administrative positions were excluded from the study.

The dependent variables were Prevalence of MAEs and Socio-demographics characteristics, work-related factors, professional related factors, and other error producing conditions were among independent variables. For the data collection a semi-structured self-administered questionnaire was prepared and used to collect data on anesthetists’ socio-demographic characteristics (an institution where the anesthetists earned, an educational award, year of experience, etc.), work-related factors (presence of written guideline for medication administration, training on medication administration, communication with other anesthetists while facing problems and availability of reporting mechanism to medication errors), Moreover, the prevalence of MAE, reporting trends of a medication error, and types of MAE were considered. MAEs were defined as any error made during the administration of anesthetic drugs regardless of how many errors were made or whether there were any adverse consequence.

Five MSc-trained anesthetists who reside in or close to the study area were involved in the data collection process. Before real data collection, the questionnaire was pretested on 10 anesthetists employed at Dilla University Hospital in order to ensure the quality of the data. Before participants began the survey, we gave each participant a page of material outlining the study’s goals and the primary investigator’s contact information.

Given the nature of web-based questionnaires (absence of the researcher), respondents were motivated to answer more honestly because we maintained their anonymity. We secured the study participants’ information and upheld their confidentiality. To prevent response bias, which occurs when respondents lose interest and give answers that are consistent with the question, the survey questioner took between five and ten minutes to complete. For validation reasons, the gathered data were imported into Epidata version 4.2. Version 20 of the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) was used to analyze the data).

As frequencies and percentages, the descriptive statistics’ findings for nominal categorical variables are enumerated. For statistical inference, we used nonparametric tests. In order to create charts, we used SPSS and Microsoft Excel.The study population was described with regard to pertinent factors using statistics including frequencies, proportions, and summary statistics (mean, median, IQR, and standard deviation), which were then displayed in tables and graphs. Finally, factors from the multivariable analysis were deemed statistically significant if their p-value was less than 0.05. To measure the degree of relationship between medication administration error and its predictors, an adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was taken into account.

Results

The study included 108 anesthetists in total, yielding a response rate of 42.35%. One hundred four were discovered to be complete and analayzed. The mean (standard deviation) age of anesthetists was 29.06(± 4.007) years. Male participants made up 82.7% of the total. Approximately 67 (64.4%) of the participants had over five years of work experience in clinical anesthesia. The majority of study participants 71 (68.3%) had a master’s degree in science (MSc) or higher (Table 1).

Regarding the characteristics of the participants’ working environments, more than two thirds of participants 90 (86.54%) worked exclusively in governmental hospitals. In addition to their clinical work, more than half of the respondents were involved in academic and teaching endeavors. The availability of medications at 85(81.73%) of the participants’ working hospitals was revealed to be insufficient or not continuous. However, during their clinical practice, 91 (87.50%) of the participants did not receive training on medication administration error. Additionally, only 30 (28.85%) of respondents indicated that their hospital has a working system for reporting medication errors (Table 2).

In accordance with the findings, 43 (41.3%) of respondents admitted to using anesthetic medications that were prepared by students under supervision for their usual clinical practice. Additionally, 53 (51.00%) of the participants stated that they labeled the syringe first before withdrawing the drug when preparing the medication. The remaining participants (49.00%) admitted that they label the srying after withdrawing the anesthetic drugs. Before administering anesthetic medications, only 38 (36.5%) of those surveyed claimed to always double check, which entails two people making sure the same information is accurate. During their clinical practice, more than half (64.4%) of participants experienced drug administration error. 39 (37.50%) of the respondents revealed that they experienced more medication errors while on night shifts (Table 3).

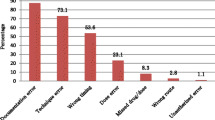

According to the finding of this study, giving drugs in wrong route were the frequent type of medication error reported by majority of participants who admitted MAEs (15.38%) followed by wrong dose (9.62%) and intended drug not given at aparticular time (7.69%) (Fig. 1).

The more frequent complication of medication administration error observed by participants is prolonged hospital stay following surgery and anesthesia(25%) (Fig. 2).

Underlying root causes of medication administration errors (MAEs)

In the bivariate analysis, the availability of the medication administration guideline, whether or not participants always double-check anesthetic drugs before administration, by whom typically anesthetic drugs prepared, how anesthetic drugs drown in the syringe, and whether or not anesthetists communicate with other anesthetists when they faced difficulties during the drug administration process were significantly associated with MAEs. However, the multivariable logistic regression model found a significant relationship between whether participants always double-check anesthetic drugs before administration and who typically prepares anesthetic drugs.

Anesthetists who did not always double-check their anesthetic drugs before administration had a 3.51 higher risk of developing MAEs compared to those who always double-check anesthetic drugs before administration (AOR = 3.51; 95% CI: 1.34, 9.19). Additionally, participants who administer medications that have been prepared by someone else are about five times more likely to experience MAEs than participants who prepare their own anesthetic medications prior to administration (AOR = 4.95; 95% CI: 1.54, 15.95) (Table 4).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the frequency and underlying root causes of errors during medication administration among anaesthetists working in Amhara region, Ethiopia. The results of this study indicated that majority (64.4%) of anaesthetists had admitted MAEs. This result is comparable to the findings of a study from Saudi Arabia, which found that 69% of respondents had made at least one medication error while administering anaesthesia [15]. However, the study results from Santa Catarina, India and canada shows a higher rate of occurrence, where the authors reported that the prevalence of drug administration errors during anaesthesia practice among anesthesiologists is 91.8%, 75.6% and 85% respectively [12, 16, 17]. That might be because their study design was different from ours and they used direct observation to assess drug administration error in addition to a self-reported survey.

Even though Amponash et al. found that errors were more likely to occur during night shifts, our study found no correlation between shift of working time and MAEs. This could be as a result of that more than two thirds of participants said they worked an alternative shift with a similar caseload during both shifts. Additionally, this could be the result of the fact that fatigue brought on by a heavy workload is a significant contributing factor to MAEs regardless of the time of working shift [18]. Furthermore, this is supported by the result that shown medication errors are believed to occur at any time by the majority of respondents in a Saudi Arabian study [19].

Because of the multitasking nature of anaesthesia practise, it is possible for clinicians to misidentify a drug while attending to other tasks [20]. According to reports, the two most important preventive measures for MAEs are the use of color-coded syringes and double-checking the medication, which involves two people verifying the same information [7, 21]. However, nearly all participants in this study (97.11%) stated that their hospital does not have color-coded syringes. Also, 63.5% of anaesthetists don’t always double-check their medications before administration and almost half (49%) of the participants claimed they withdraw the medication before labelling the syringe. These factors could lead to incorrect syringe identification and, even worse, anaesthetists administering drugs incorrectly because they conflict with preventive standards for MAEs [11, 22]. This is supported by a related study from a hospital in China, where Zhang et al. reported that incorrectly labelled syringes are the root cause of syringe swapping, or the unintentional administration of the wrong medication. [23]. Additionally, inadequate syringe labelling was ranked by study participants as the third most important factor contributing to medication errors, behind a heavy workload and haste, according to the literature [20]. Instead, it is reported that two of the five strong evidence-based recommendations for minimising errors in the administration of intravenous anaesthetic drugs, labeling syringes always before administering drugs and double-checking labels with a second person using a formal organisation of drug drawers and workstations are the measures that lower MAEs [21].

Among participants who admitted MAEs, 51.92% did not report any drug administration related errors while they were at work. Despite the fact that this finding is alarming, it is consistent with earlier studies that have shown that most respondents who admitted to MAEs were unwilling to report even one drug error over the course of their careers [10, 14, 24]. Alternatively, it could be explained by scientific data showing that clinicians experience shame, guilt, or blame after disclosing their errors, which may discourage them from reporting errors [9,10,11].

When asked why they were reluctant to report their errors during medication administration process, 30.77% of respondents stated that they were concerned about the medicolegal repercussions of doing so. The final two reasons given by respondents as reasons why they were unable to disclose their errors were: not knowing to whom it was reported (24.04%) and fear of judgment by colleagues.

In response to a question, more than half of participants (53.8%) said that their hospital had no incident reporting system at all. Similarly, participants admitted they had no idea when or how their hospitals conducted the reported error audits. This finding might point to a lack of knowledge among clinicians regarding the hospital’s policies for reporting errors. It is consistent with earlier studies, where 23.9% of respondents had medication errors but only 6% were willing to admit to their errors [25].

In this study, participants who administer medications that have been prepared by someone else are about five times more likely to experience MAEs than participants who prepare their own anesthetic medications prior to administration. This may be the result of poor communication among anesthetists, as shown by the the study that only 35.57% of participants spoke to a colleague anesthetist when in doubt about drug administration process. This finding is in line with research by Leonard et al., which found that participants’ poor communication led to 48% of medication errors and 70% of medication error related adverse event [26].

The findings of this study showed that the presence of MAEs among the participants was significantly related to whether anaesthetists consistently double-check their anaesthetic drugs before administration. As a result, there was a 3.51 increase in the risk of MAEs among anaesthetists who did not always check their anaesthetic medications before administration. Among the potential safety advantages of double checking medications before administration is the reduction of endogenous (that originate from one person) and exogenous errors (that result from external factors, such as illegible text) [27]. our finding is supported by a randomized control trial from the United States, where multivariate regression revealed that double-checked administrations were significantly associated with a lower risk of any type of error [28].

Conclusion

Our study found a considerable rate of errors in the administration of anaesthetic drugs. The failure to always double-check medications before administration and the use of drugs prepared by another anaesthetist were identified to be risk factors for drug administration errors. To ensure the safety of surgical patients, it is imperative to prioritise preventing these clinical errors. As a result, preparing anaesthetic medications on one’s own and double checking the drugs before administration will reduce the frequency of medication administration errors and enhance patient outcomes.

Limitation

As a survey study, the study’s main limitation is that it relies on “self-report,“ which could have overstated or understated the frequency of drug admnistration errors. Despite the fact that our data show a significant incidence rate of anaesthetic medication errors, the sample size was too small to fully represent the entire anesthetists community. Therefore, for any relevant future investigations, we suggest undertaking a direct observational study with a larger sample size.

Abbreviations

- MAEs:

-

Medication administration errors

References

Wang Y, Du Y, Zhao Y, Ren Y, Zhang W. Automated anesthesia carts reduce drug recording errors in medication administrations—a single center study in the largest tertiary referral hospital in China. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:11–5.

Workie MM, Chekol WB, Fentie DY, Bizuneh YB, Ahmed SA. Drug safety management in the operation room of referral hospital: cross-sectional study. Int J Surg Open. 2020;26:97–100.

Cooper L, Nossaman B. Medication errors in anesthesia: a review. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2013;51(1):1–12.

Evley R, Russell J, Mathew D, Hall R, Gemmell L, Mahajan R. Confirming the drugs administered during anaesthesia: a feasibility study in the pilot National Health Service sites, UK. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(3):289–96.

Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25–34.

Mekonnen AB, Alhawassi TM, McLachlan AJ, Brien J-aE. Adverse drug events and medication errors in african hospitals: a systematic review. Drugs-real world outcomes. 2018;5(1):1–24.

Annie SJ, Thirilogasundary MR, Kumar VRH. Drug administration errors among anesthesiologists: the burden in India–A questionnaire-based survey. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(2):220.

Webster C, Merry A, Larsson L, McGrath K, Weller J. The frequency and nature of drug administration error during anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29(5):494–500.

Merry AF, Webster CS, Hannam J, Mitchell SJ, Henderson R, Reid P et al. Multimodal system designed to reduce errors in recording and administration of drugs in anaesthesia: prospective randomised clinical evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343.

Aldossary DN, Almandeel HK, Alzahrani JH, Alrashidi HO. Assessment of medication errors among Anesthesia Clinicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey study. Global J Qual Saf Healthc. 2022;5(1):1–9.

Rayan AA, Hemdan SE, Shetaia AM. Root cause analysis of blunders in anesthesia. Anesth Essays Researches. 2019;13(2):193.

Orser BA, Chen RJ, Yee DA. Medication errors in anesthetic practice: a survey of 687 practitioners. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48(2):139–46.

Salam A, Segal DM, Abu-Helalah MA, Gutierrez ML, Joosub I, Ahmed W, et al. The impact of work-related stress on medication errors in Eastern Region Saudi Arabia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(1):30–5.

McCawley D, Cyna A, Prineas S, Tan S. A survey of the sequelae of memorable anaesthetic drug errors from the anaesthetist’s perspective. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;45(5):624–30.

Aldossary DN, Almandeel HK, Alzahrani JH, Alrashidi HO. Assessment of medication errors among Anesthesia Clinicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey study. Global J Qual Saf Healthc. 2021;5(1):1–9.

Erdmann TR, Garcia JH, Loureiro ML, Monteiro MP, Brunharo GM. Profile of drug administration errors in anesthesia among anesthesiologists from Santa Catarina. Brazilian J anesthesiology (Elsevier). 2016;66(1):105–10.

Annie SJ, Thirilogasundary MR, Hemanth Kumar VR. Drug administration errors among anesthesiologists: the burden in India - A questionnaire-based survey. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(2):220–6.

Erdmann TR, Garcia JHS, Loureiro ML, Monteiro MP, Brunharo GM. Profile of drug administration errors in anesthesia among anesthesiologists from Santa Catarina. Revista brasileira de anestesiologia. 2016;66:105–10.

Alshammari TM, Alenzi KA, Alatawi Y, Almordi AS, Altebainawi AF. Current situation of medication errors in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide observational study. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(2):e448–e53.

Smith K, Sharp C, Smith E, Currie M, Hall K. Interdisciplinary Anesthesia Tray Revision Project: reducing the opportunity for human error. Int J Anesth Anesthesiol. 2018;5:1–6.

Jensen L, Merry A, Webster C, Weller J, Larsson L. Evidence-based strategies for preventing drug administration errors during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2004;59(5):493–504.

Orser BA, Hyland S, Sheppard I, Wilson CR. Improving drug safety for patients undergoing anesthesia and surgery. Can J Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie. 2013;60(2):127–35.

Zhang Y, Dong Y, Webster C, Ding X, Liu X, Chen W, et al. The frequency and nature of drug administration error during anaesthesia in a C hinese hospital. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57(2):158–64.

Alsulami SL, Sardidi HO, Almuzaini RS, Alsaif MA, Almuzaini HS, Moukaddem AK, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice on medication error reporting among health practitioners in a tertiary care setting in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2019;40(3):246.

Al-kaabba A, Hussein G, Kasule O, Alhaqwi A. Disclosing medical errors in tertiary hospitals in Saudi Arabia: cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int J Appl Math Comput Sci. 2016;3:75–83.

Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13(suppl 1):i85–i90.

Koyama AK, Maddox CS, Li L, Bucknall T, Westbrook JI. Effectiveness of double checking to reduce medication administration errors: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(7):595–603.

Modic MB, Albert NM, Sun Z, Bena JF, Yager C, Cary T, et al. Does an insulin double-checking procedure improve patient safety? J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(3):154–60.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all data collectors and study participants.

Funding

There is no financing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Meseret firde came up with the idea, carried out the study, including data entry, statistical analysis, article preparation, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Debre Tabor University College of Health Science Ethical Review Committee, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia, granted ethical approval for this study. Before they began the survey, the participants’ written informed consent was obtained for their participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Firde, M. Incidence and root causes of medication errors by anesthetists: a multicenter web-based survey from 8 teaching hospitals in Ethiopia. Patient Saf Surg 17, 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-023-00367-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-023-00367-8