Abstract

Introduction

Gender dysphoria (GD) is characterized by the incongruence between one’s experienced and expressed gender and assigned-sex-at-birth; it is associated with clinically significant distress. In recent years, the number of young patients diagnosed with GD has increased considerably. Recent studies reported that GD adolescents present behavioural and emotional problems and internalizing problems. Furthermore, this population shows a prevalence of psychiatric symptoms, like depression and anxiety. Several studies showed high rates of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviour in GD adolescents. To increase understanding of overall mental health status and potential risks of young people with GD, this systematic review focused on risk of suicide and self-harm gestures.

Methods

We followed the PRISMA 2020 statement, collecting empirical studies from four electronic databases, i.e., PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science.

Results

Twenty-one studies on GD and gender nonconforming identity, suicidality, and self-harm in adolescents and young adults met inclusion criteria. Results showed that GD adolescents have more suicidal ideation, life-threatening behaviour, self-injurious thoughts or self-harm than their cisgender peers. Assessment methods were heterogeneous.

Conclusion

A standardised assessment is needed. Understanding the mental health status of transgender young people could help develop and provide effective clinical pathways and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gender dysphoria (GD) is a condition characterized by a marked incongruence between one’s experienced and expressed gender and the one assigned at birth and is often associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, especially when reported early [1]. In recent years, the number of young patients diagnosed with GD or and gender-diverse identity—including nonbinary and questioning sexual identities—has considerably increased [2,3,4,5]. Current studies document that this population may be exposed to a higher risk of adverse events affecting health status and well-being [6, 7]. This further impacted this vulnerable population, with the most negative consequences for those who experience a gender not congruent with the one they were assigned at birth [8,9,10]. Indeed, children and adolescents with GD and transgender or transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) are described as a psychologically and socially vulnerable population, facing a wide range of physical and mental health concerns that could benefit from early intervention [11,12,13]. GD during adolescence develops in individuals whose brain is still developing to reach full maturity only some years later, hence the need to dedicate special attention to this population.

As a population perceiving gender minority stress [14], adolescents with GD are likely to lack social acceptance and suffer stigma laid upon them by others [15], but also tend to internalisation [16]. A corollary may be that several studies found adolescents with GD, compared to their age-matched cisgender peers, to show more often behavioural and emotional problems and higher levels of individual distress-generating internalising problems, rather than environment-perturbing externalising problems [17,18,19]. Consequently, adolescents with GD show a higher prevalence of psychiatric issues, such as depression and anxiety disorders [17, 20, 21], likely due to social stigma.

Adolescents and young adults with GD and gender-diverse identity report higher suicidal thinking, planning, and attempts as well as non-suicidal self-harming thoughts and behaviours (NSSI) than the general population [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Suicidality is an umbrella term including suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviours, and suicide attempts and plans which are correlated to the desire to die [33]; we will use suicidality sparingly in this paper and focus instead upon the above-mentioned specific terms, when possible. Non-suicidal self-harming behaviours and thoughts, however, refer to self-injurious acts without intending to end one’s own life, but involve self-punishment or negative emotion regulation [34]. In both cases, early age at onset has been identified as an important vulnerability factor, with onset during childhood and adolescence being associated with a poorer prognosis [17], based on different surveys of high-school students [31]. For example, in New Zealand, 20% of students with GD reported attempting suicide in the past 12 months, compared to 4% of all students [35]. Similarly, in the United States, 15% of students with GD reported a suicide attempt requiring medical treatment in the last 12 months, compared to 3% of all students [36,37,38]. In another American survey, 41% of students with GD reported having attempted suicide during their lifetime, compared to 14% of all students [39]. Moreover, Surace and her colleagues [40] found a mean prevalence of 28.2% for NSSI, 28.0% for suicidal ideation, and 14.8% for suicide attempts in young TGNC clinical populations up to 25 years old.

Besides aspects of GD like body dysmorphic disorder, feeling uncomfortable in one’s own body, and hopelessness about obtaining gender-affirming medical procedures, a possible contribution to elevated suicidal risk and behaviours in the GD population might lie within the social stigma experienced by TGNC adolescents, such as discrimination, prejudice, social stress, and ostracism within the peer group and/or family [41]. Suicidal ideation and self-injurious behaviours generally relate to significant emotional problems, such as depressive and anxiety symptoms, which in turn trigger psychosocial and biological imbalance, could increase the wish to die [42,43,44,45], thus adding to the above.

In summary, several studies have shown higher rates of suicidal and non-suicidal self-harming thoughts and behaviours in adolescents and young adults with GD and gender-diverse identity—such as nonbinary and questioning sexual identity—compared to their male and female cisgender peers. However, the evidence heretofore is piecemeal, probably due to social stigma currently associated with GD and the concern of stigmatising individuals suffering from this condition. To better understand the mental state of adolescents and young adults with TGNC, we conducted a systematic review focusing on the risk for suicide and self-harming gestures in the GD population. The aim of this review was to estimate the frequency of suicidal and self-harm behaviour in adolescents and young adults with GD, comparing them with cisgender adolescents where possible.

Method

We performed a systematic review in compliance with the 2020 PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses [46] to increase comprehensiveness and transparency of reporting.

Information sources and database search

To systematically collect empirical studies on the possible relation between suicidality/self-harming and GD in adolescents and young adults, several keywords were used to search for appropriate publications in four electronic databases, i.e., PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science since their inception and no date or language restriction.

Authors conducted the search separately in each database using the following agreed upon search strategy for PubMed and adapting the search for the other databases: (suicid* OR self-injur* OR self-harm* OR self-inflict* OR self-lesion*) AND (gender dysphori* OR transgender) AND (child* OR adolesc* OR "young adult*" OR youth* OR "school age"). Since the terms GD and transgender are used by many people as synonymous, in our searches we used both terms to identify possible eligible articles.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were a study published in a peer-reviewed journal, reporting data on suicide and related behaviours (thinking, planning, and attempts) and/or non-suicidal self-harming thoughts and acts (using methods that reliably obtain the desired result) in adolescent and young adult (14–27 years old) samples with GD/transgender status/gender diverse identity.

Exclusion criteria were studies conducted on children or adult samples and those with mixed populations not providing data for adolescents and young adults separately. Also, opinion papers, such as editorials, letters to the editor, and hypotheses without providing data were excluded, as well as case reports or series, reviews/meta-analyses, animal studies, studies with inadequate/poor methodology and inadequate reporting of data, unfocused, or unrelated to the subject matter. All inter- and intra-database duplicates were removed, as well as abstracts, meeting presentations and studies presenting incomplete data.

Although reviews and meta-analyses were not included, their reference lists were screened to identify additional eligible publications. Eligibility for each study was decided with Delphi rounds among all authors until complete consensus was reached.

Data extraction

The analysis was conducted by all authors, who applied the eligibility criteria on each database. Each author conducted the selection process separately from others; at a final step, all authors compared their results in Delphi rounds (either in-person or remotely) aimed at obtaining full consensus.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment

Data collected for each study included country of origin, number of paediatric patients, demographic information (age and biological sex), presence/absence of GD and if present, type of GD, and clinical symptoms focused on self-harm (suicide behaviour, suicidal ideation, suicidal intent and planning, non-suicidal self-harm, and other self-injurious behaviour).

The evaluation of the risk of bias was conducted by a quality index derived from the Qualsyst’ Tool [47]. The quality of selected studies was assessed independently by all investigators and disagreements were resolved by consensus (results of risk-of-bias for all studies in the Additional file 1).

Results

Identified studies

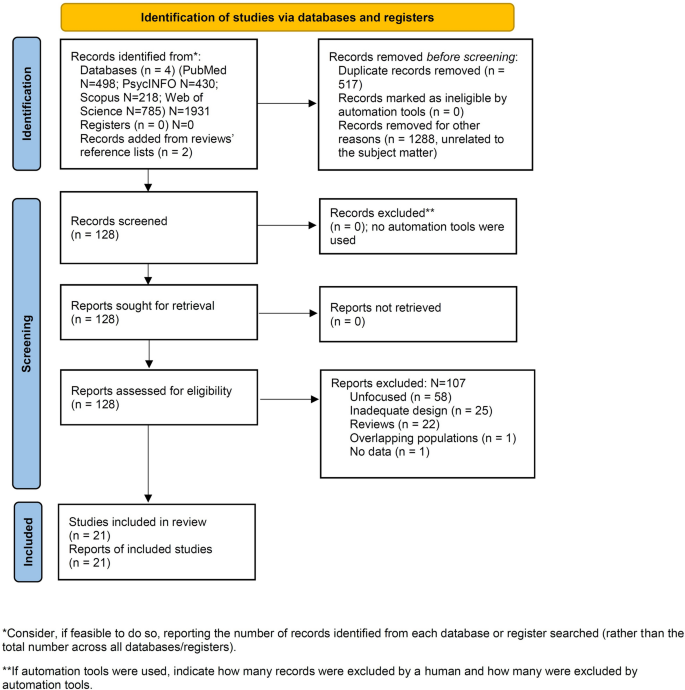

On February 7, 2023, we located 1416 articles (Fig. 1, PRISMA flowchart) [39], of which 128 articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these papers, 107 articles were excluded according to eligibility criteria; 21 dealing with the relationship between GD and gender non-conforming identity, and suicidality and self-harm in adolescents and young adults met inclusion criteria.

For the purpose of this systematic review, we have focused our analyses on these 21 studies. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flow diagram showing search results.

Due to the breadth of the topic and the variety of variables included in this systematic review, the subject matter was organized according to the categories of psychopathological symptoms of interest in the study (Tables 1 and 2) and a final mixed category (Table 3). Of 21 studies meeting the inclusion criteria, there were 2 studies where self-harming behaviours and thoughts was the outcome in TGNC adolescents (Table 1), 6 studies where suicide was the outcome (Table 2), and 13 studies where the outcome was committing suicide combined to self-injurious attitudes (Table 3).

The 21 studies were mainly from the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe. Included studies were also conducted in China, Iran, Turkey, Canada and Australia. Studies were non-interventional and observational, with 17 being cross-sectional or retrospective and 4 longitudinal.

GD and non-suicidal self-harming ideation and behaviours were investigated by two studies [48, 49], GD and suicidality by six studies [6, 17, 24, 29, 39, 51], and GD and both suicidality and non-suicidal self-harm by 13 [11, 21, 22, 25, 30, 50, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58]; of these studies, four [11, 21, 55, 58] detected the presence of internalizing problems (depressive and anxiety disorders) in GD adolescents and young adults. Detailed results are provided in the Additional file 1.

Summary results

Detailed results of each study are shown in Tables 1–3 and in the Additional file 1. We will here summarise results in GD and transgender populations regarding studies of (1) non-suicidal self-harm, (2) suicidal ideation and attempts, and (3) non-suicidal self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts combined.

-

- Non-suicidal self-harming was explored in two studies [48, 49]; transgender adolescents showed higher tendency toward self-harm ideation than cisgender adolescents, while non-suicidal self-inflicted behaviours were more common in cisgender males and females than among transgender adolescents [49]. AFAB adolescents showed nominally more lifetime and current NSSI than AMAB, but this did not reach statistical significance [48] (Table 1).

-

- Suicidal thinking and attempts only were examined in six studies [6, 17, 24, 29, 39, 51] and generally identified a high prevalence in GD/transgender populations of suicide behaviours and attempts, ranging from 14.3% of severe suicidal ideation in Heino et al. [29] to a cumulative “high risk” of 80.9% in Alizadeh Mohajer et al. [6]; however, studies used different assessment instruments, so it becomes difficult to draw conclusions as to the real extent of suicidality in our target population. Gender-diverse adolescents displayed high suicidal ideation (Table 2). Transgender/GD adolescents displayed more suicidal behaviour than cisgender adolescents, either males or females [39]. Suicidality did not differ between AMAB and AFAB transgender adolescents/younger adults [51].

-

- Suicidality and non-suicidal self-harm combined were explored in thirteen studies [11, 21, 22, 25, 30, 50, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Both NSSI and suicidality were higher in transgender/GD youths than in cisgender participants. AMAB and AFAB showed higher NSSI and suicidality rates than cisgender boys and girls [11] (Table 3).

Additional considerations will be detailed further on.

Discussion

The last decade has seen an increase in cases of GD in adolescents worldwide and our knowledge of the epidemiological and clinical features continues to evolve [59]. An adequate understanding of the phenomenon and any related symptoms is important for the early management and possible prevention of distress. Indeed, the literature has highlighted the existence of a high association of psychological and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with GD.

Several studies used different methods to investigate whether transgender identity and clinical outcomes in the general adolescent population are related [6, 17, 21, 22, 24, 25, 29, 30, 39, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. The present review focused particularly on high-severity psychological symptoms in young people, such as self-harm and suicidal symptomatology. Indeed, the results of the studies underline a statistically significant correlation between youth TGNC—including gender dysphoric, non-binary and questioning adolescents—and prevalence of suicidal thinking and plans/attempts and self-harming thoughts and behaviours compared to cisgender populations [20, 29, 60,61,62,63,64,65]. Currently, there is a dearth of results from population-based samples, hence generalizing current findings is still very premature [59]. Despite progress and availability of resilience factors to face stigma and discrimination in some societies and social groups, there are considerable anti-LGBT attitudes in some countries and other social groups, ensuing in GD adolescents showing more mental symptoms and distress compared to cisgender peers [52, 66, 67]. Gender dysphoric adolescents show higher rates of depression leading to suicidal risk and engage in more self-injurious behaviours than their cisgender peers, confirming that a significant proportion of this population experience severe suicidal ideation and almost one third attempt suicide [4]. Other studies highlight that half of transgender youths are diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorders as well as poorer overall health and sleep quality [11, 66, 68]. Furthermore, puberty appears to exacerbate mental health problems in people with GD [30].

The main theoretical models, such as the gender minority stress model [69], identify potential risk factors among transgender individuals, link exposure to stigma, discrimination, and lack of social support. Previous research identified sexual minority status as a fundamental risk factor for own life-threatening behaviours [70]. In fact, adolescents diagnosed with GD experience victimization from their peers, negative parental reactions to their gender-nonconforming expression and identity, and family violence. These exogenous factors often lead transgender individuals to experience personal distress and isolation, which might elicit higher rates of own-life-threatening behaviours, such as suicidal attempts and ideation and self-harm thoughts than their heterosexual peers [70,71,72,73].

Overall, results of the studies included in this systematic review confirmed that, compared to cisgender adolescents, TGNC adolescents reported a significantly higher frequency of suicidal attempts, suicidal thoughts, making suicide plans, self-harm ideation and deliberately participating in self-harm acts. Higher depressive and anxiety symptoms and lower overall physical health were also positively associated with GD [11, 55, 57, 58, 74].

However, results were heterogeneous. Specifically, Wang and colleagues [11] indicated that among the gender minority groups transgender girls had the greater risk of planning and attempting suicide, transgender boys had the highest risk of performing deliberate self-harm, and questioning youth AFAB had the highest risk of suicidal ideation. Similar results were obtained in another study [24], with the risk ratios analysis highlighting the greater rate of suicidality among birth-assigned females. This pattern is consistent with many other studies showing that suicidality is more common among AFAB adolescents than it is among AMAB youth [75]. Some studies found possible gender differences between AFAB and AMAB and possible consequences for their mental health, suggesting that although AMAB might experience more stigmatization and preconceptions, AFAB youth seem to cope differently with distress [17, 25, 48]. Nevertheless, this outcome was different from Toomey and colleagues’ work [39], which found that transgender boys had a higher rate of attempted suicide than transgender girls.

At any rate, despite these within-group discrepancies, general findings emerging from quantitative studies provide evidence that a large proportion of adolescents referred for GD and other transgender youth, whether “AFAB” or “AMAB”, have a substantial co-occurring history of psychosocial and psychological vulnerability, causing a higher risk for suicidal ideation and life-threatening behaviours, such as self-harm thoughts and self-injurious gestures [70, 76].

Since society is becoming increasingly liquid according to Zygmunt Bauman [77], more cases of transgender states and GD are anticipated to occur; this will mean that we will have more of the general population at enhanced risk for self-harming acts, suicidal thinking, and suicidal behaviour. Under this perspective, it should be important to develop a comprehensive psychological assessment aimed at identifying people at risk of the above behaviours so to enforce preventive programmes [78,79,80].

For this reason, results provided by this systematic review may enhance the knowledge of health professionals about adolescents referred for GD. Furthermore, a better understanding of the mental health status of transgender youth and the associated risks could help to develop and provide effective interventions. The need for more knowledge and tools is also a key aspect of supporting each individual properly [30, 81]. Finally, increasing social awareness and scientific knowledge can also help target support programs for parents. Indeed, parents could benefit from interventions dedicated to understanding the impact of attitudes, behaviours and decisions, as well as assisting them in the therapeutic paths they take with their children with GD [70].

Limitations. This review contains heterogeneous data that could not be subjected to a meta-analysis. Heterogeneity regarded the instruments used to assess the populations included and the variables examined. To add to the high heterogeneity, the population under study belonged to multiple categories, such as cisgender males, cisgender females, individuals assigned female at birth whose experienced gender was male (so-called female-to-male transgender), individuals assigned male at birth whose experienced gender was female (so-called male-to-female transgender), and nonbinary. Often studies did not differentiate possible transgender from nonbinary identities. We attempted at focusing on GD only, but had to deal also with other populations as well, since the literature treats these populations as they were one and the same, which of course is not the case. Furthermore, a distinction between self-harm and suicide attempts was not always possible. Moreover, the social stigma laid upon gender diverse populations and current cultural trends may have directly or indirectly affected the writing of this review and its final results and conclusions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the overall findings emerging from this review provide evidence that a large proportion of adolescents with GD have a substantial concomitant history of psychosocial and psychological vulnerability, with a higher risk of suicidal ideation, life-threatening behaviour, and self-injurious thoughts or self-harm. Understanding the mental health status of transgender young people could help developing and providing effective clinical pathways and interventions. The relatively new issue of suicide in adolescent/young adult populations currently suffers from poor assessment standardization. There is a need for standardized assessment, culturally adapted research, and destigmatisation of this socially vulnerable population to address the issue of increased suicidal thinking and attempts.

Availability of data and materials

N/A.

References

American Psychiatric Association. diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Zucker KJ. Epidemiology of gender dysphoria and transgender identity. Sex Health. 2017;14(5):404–11. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17067.

Indremo M, White R, Frisell T, Cnattingius S, Skalkidou A, Isaksson J, Papadopoulos FC. Validity of the gender dysphoria diagnosis and incidence trends in Sweden: a nationwide register study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95421-9.4.

Thompson L, Sarovic D, Wilson P, Sämfjord A, Gillberg C. A PRISMA systematic review of adolescent gender dysphoria literature: 1) epidemiology. PLOS Glob Publ Health. 2022;2(3):e0000245. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000426.

Oshima Y, Matsumoto Y, Terada S, Yamada N. Prevalence of gender dysphoria by gender and age in japan: a population-based internet survey using the utrecht gender dysphoria scale. J Sex Med. 2022;19(7):1185–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.03.605.

Alizadeh Mohajer M, Adibi A, Mozafari AA, Sahebi A, Bakhtiyari A. Suicidal ideation in patients with gender identity disorder in western Iran from March 2019 to March 2020. Int J Med Toxicol Forensic Med. 2020;10(4):31353. https://doi.org/10.32598/ijAMABm.v10i4.31353.

Shin KE, Baroni A, Gerson RS, Bell KA, Pollak OH, Tezanos K, Spirito A, Cha CB. Using behavioral measures to assess suicide risk in the psychiatric emergency department for youth. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01507-y.

Perl L, Oren A, Klein Z, Shechner T. Effects of the COVID19 pandemic on transgender and gender non-conforming adolescents’ mental health. Psychiatr Res. 2021;302:114042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114042.

Hawke LD, Hayes E, Darnay K, Henderson J. Mental health among transgender and gender diverse youth: an exploration of effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2021;8(2):180–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000467.

Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML, Banyard V, Goodman KL, Jones LM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceptions of health and well-being among sexual and gender minority adolescents and emerging adults. LGBT Health. 2022;9(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0238.

Wang Y, Yu H, Yang Y, Drescher J, Li R, Yin W, Yu R, Wang S, Deng W, Jia Q, Zucker KJ, Chen R. Mental health status of cisgender and gender-diverse secondary school students in China. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(10):e2022796. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22796.

Andresen JB, Graugaard C, Andersson M, Bahnsen MK, Frisch M. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health problems in a nationally representative study of heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual danes. World Psychiatr. 2022;21(3):427–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21008.

Sun S, Xu S, Guy A, Guigayoma J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Operaio D, Chen R. Analysis of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk among younger adults in china by gender identity and sexual orientation. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e232294. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.2294.

Hunter J, Butler C, Cooper K. Gender minority stress in trans and gender diverse adolescents and young people. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26(4):1182–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211033187.

Joseph AA, Kulshreshtha B, Shabir I, Marumudi E, George TS, Sagar R, Mehta M, Ammini AC. Gender issues and related social stigma affecting patients with a disorder of sex development in India. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(2):361–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0841-0.

Jackman KB, Dolezal C, Bockting WO. Generational differences in internalized transnegativity and psychological distress among feminine spectrum transgender people. LGBT Health. 2018;5(1):54–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0034.

Fisher AD, Ristori J, Castellini G, Sensi C, Cassioli E, Prunas A, Mosconi M, Vitelli R, Dèttore D, Ricca V, Maggi M. Psychological characteristics of Italian gender dysphoric adolescents: a case-control study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(9):953–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0647-5.

de Vries AL, Doreleijers TA, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(11):1195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02426.x.

Zucker KJ, Wood H, Singh D, Bradley SJ. A developmental, biopsychosocial model for the treatment of children with gender identity disorder. J Homosex. 2012;59(3):369–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.653309.

Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):44–57. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1115753.

Kozlowska K, McClure G, Chudleigh C, Maguire AM, Gessler D, Scher S, Ambler GR. Australian children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: clinical presentations and challenges experienced by a multidisciplinary team and gender service. Hum Syst Ther, Cult Attach. 2021;1(1):70–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/26344041211010777.

Skagerberg E, Parkinson R, Carmichael P. Self-harming thoughts and behaviors in a group of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Int J Transgenderism. 2013;14(2):86–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2013.817321.

Aitken M, VanderLaan DP, Wasserman L, Stojanovski S, Zucker KJ. Self-Harm and suicidality in children referred for gender dysphoria. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(6):513–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.001.

de Graaf NM, Steensma TD, Carmichael P, VanderLaan DP, Aitken M, Cohen-Kettenis PT, de Vries ALC, Kreukels BPC, Wasserman L, Wood H, Zucker KJ. Suicidality in clinic-referred transgender adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(1):67–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01663-9.

Thoma BC, Salk RH, Choukas-Bradley S, Goldstein TR, Levine MD, Marshal MP. Suicidality disparities between transgender and cisgender adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20191183. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1183.

Mann GE, Taylor A, Wren B, de Graaf N. Review of the literature on self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in gender-diverse children and young people in the United Kingdom. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;24(2):304–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518812724.

Dickey LM, Budge SL. Suicide and the transgender experience: a public health crisis. Am Psychol. 2020;75(3):380–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000619.

Hatchel T, Polanin JR, Espelage DL. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: meta-analyses and a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2021;25(1):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1663329.

Heino E, Fröjd S, Marttunen M, Kaltiala R. Transgender identity is associated with severe suicidal ideation among finnish adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2021-0018.

Hartig A, Voss C, Herrmann L, Fahrenkrug S, Bindt C, Becker-Hebly I. Suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harming thoughts and behaviors in clinically referred children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;27(3):716–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211073941.

Biggs M. Suicide by clinic-referred transgender adolescents in the United Kingdom. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51(2):685–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02287-7.

Faruki F, Patel A, Jaka S, Kaur M, Sejdiu A, Bajwa A, Patel RS. Gender dysphoria in pediatric and transitional-aged youth hospitalized for suicidal behaviors: a cross-national inpatient study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2023;25(2):46284. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.22m03352.

O’Connor RC, Nock MK. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6.

Claes L, Vandereycken W. Self-injurious behavior: differential diagnosis and functional differentiation. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.10.009.

Clark TC, Lucassen MF, Bullen P, Denny SJ, Fleming TM, Robinson EM, Rossen FV. The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’12). J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):93–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.008.

Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, Ethier KA. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1.

Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, Rasberry CN, Robin L, Underwood JM. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67–71. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3.

Jackman KB, Caceres BA, Kreuze EJ, Bockting WO. Suicidality among gender minority youth: analysis of 2017 youth risk behavior survey data. Arch Suicide Res. 2021;25(2):208–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1678539.

Toomey RB, Syvertsen AK, Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20174218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4218.

Surace T, Fusar-Poli L, Vozza L, Cavone V, Arcidiacono C, Mammano R, Basile L, Rodolico A, Bisicchia P, Caponnetto P, Signorelli MS, Aguglia E. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors in gender non-conforming youths: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30(8):1147–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01508-5.

Arnold JC, McNamara M. Transgender and gender-diverse youth: an update on standard medical treatments for gender dysphoria and the sociopolitical climate. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001256.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;43(5):460–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597.

de Graaf NM, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Carmichael P, de Vries ALC, Dhondt K, Laridaen J, Pauli D, Ball J, Steensma TD. Psychological functioning in adolescents referred to specialist gender identity clinics across Europe: a clinical comparison study between four clinics. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(7):909–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1098-4.

Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Scanlon K, Kaay M, Travers R, Travers A. Prevalence of and risk and protective factors for depression in female-to-male transgender ontarians: results from the trans PULSE project. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2011;30(2):135–55. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0021.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. HTA Initiative # 13. Edmonton: Alberta Herit Found Med Res. 2004

Arcelus J, Claes L, Witcomb GL, Marshall E, Bouman WP. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among trans youth. J Sex Med. 2016;13(3):402–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.003.

Butler C, Joiner R, Bradley R, Bowles M, Bowes A, Russell C, Roberts V. Self-harm prevalence and ideation in a community sample of cis, trans and other youth. Int J Transgenderism. 2019;20(4):447–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1614130.

Mak J, Shires DA, Zhang Q, Prieto LR, Ahmedani BK, Kattari L, Becerra-Culqui TA, Bradlyn A, Flanders WD, Getahun D, Giammattei SV, Hunkeler EM, Lash TL, Nash R, Quinn VP, Robinson B, Roblin D, Silverberg MJ, Slovis J, Tangpricha V, Vupputuri S, Goodman M. Suicide attempts among a cohort of transgender and gender diverse people. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(4):570–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.026.

Yüksel Ş, Aslantaş Ertekin B, Öztürk M, Bikmaz PS, Oğlağu Z. A Clinically neglected topic: risk of suicide in transgender individuals. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2017;54(1):28–32. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2016.10075.

Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM. Mental health disparities among canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(1):44–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014.

Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, Cromwell L, Flanders WD, Getahun D, Giammattei SV, Hunkeler EM, Lash TL, Millman A, Quinn VP, Robinson B, Roblin D, Sandberg DE, Silverberg MJ, Tangpricha V, Goodman M. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173845. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3845.

Bechard M, VanderLaan DP, Wood H, Wasserman L, Zucker KJ. Psychosocial and psychological vulnerability in adolescents with gender dysphoria: a “proof of principle” study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2017;43(7):678–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1232325.

Peterson CM, Matthews A, Copps-Smith E, Conard LA. Suicidality, self-harm, and body dissatisfaction in transgender adolescents and emerging adults with gender dysphoria. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2017;47(4):475–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12289.

Mitchell HK, Keim G, Apple DE, Lett E, Zisk A, Dowshen NL, Yehya N. Prevalence of gender dysphoria and suicidality and self-harm in a national database of paediatric inpatients in the USA: a population-based, serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(12):876–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00280-2.

Karvonen M, Karukivi M, Kronström K, Kaltiala R. The nature of co-morbid psychopathology in adolescents with gender dysphoria. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114896.

Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, Stepney C, Inwards-Breland DJ, Ahrens K. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978–e220978. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978.

Kaltiala-Heino R, Bergman H, Työläjärvi M, Frisén L. Gender dysphoria in adolescence: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018;9:31–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S135432.

Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ II, Johnson CC, Joseph CL. The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):489–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012.

Bränström R, van der Star A, Pachankis JE. Untethered lives: barriers to societal integration as predictors of the sexual orientation disparity in suicidality. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(1):89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01742-6.

Garthe RC, Blackburn AM, Kaur A, Sarol JN Jr, Goffnett J, Rieger A, Reinhart C, Smith DC. Suicidal ideation among transgender and gender expansive youth: mechanisms of risk. Transgender Health. 2022;7(5):416–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0055.

Clark KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Sexual orientation-related patterns of 12-month course and severity of suicidality in a longitudinal, population-based cohort of young adults in Sweden. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(9):1931–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02326-7.

Bränström R, Stormbom I, Bergendal M, Pachankis JE. Transgender-based disparities in suicidality: a population-based study of key predictions from four theoretical models. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2022;52(3):401–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12830.

Chang CJ, Feinstein BA, Fulginiti A, Dyar C, Selby EA, Goldbach JT. A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal theory of suicide for predicting suicidal ideation among LGBTQ+ youth who utilize crisis services: the moderating effect of gender. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2021;51(5):1015–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12787.

Mezzalira S, Scandurra C, Mezza F, Miscioscia M, Innamorati M, Bochicchio V. Gender felt pressure, affective domains, and mental health outcomes among transgender and gender diverse (TGD) children and adolescents: a systematic review with developmental and clinical implications. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;20(1):785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010785.

Wolford-Clevenger C, Flores LY, Stuart GL. Proximal correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender and gender diverse people: a preliminary test of the three-step theory. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2021;51(6):1077–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12790.

Lehavot K, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC. Factors associated with suicidality among a national sample of transgender veterans. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2016;46(5):507–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12233.

Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, Mimiaga MJ. Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: a matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(3):274–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264.

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2007;37(5):527–37. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527.

D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Salter NP, Vasey JJ, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2005;35(6):646–60. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.646.

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR, Howell TJ, Hubbard S. Parent’reactions to transgender youth’gender nonconforming expression and identity. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2005;18(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J041v18n01_02.

Grossman AH, D’augelli AR, Salter NP. Male-to-female transgender youth: gender expression milestones, gender atypicality, victimization, and parents’ responses. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2006;2(1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.1300/J461v02n01_04.

Randall AB, van der Star A, Pennesi JL, Siegel JA, Blashill AJ. Gender identity-based disparities in self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among pre-teens in the United States. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12937.

Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, Alonso J. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:265–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1.

Horwitz AG, Berona J, Busby DR, Eisenberg D, Zheng K, Pistorello J, Albucher R, Coryell W, Favorite T, Walloch JC, King CA. Variation in suicide risk among subgroups of sexual and gender minority college students. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2020;50(5):1041–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12637.

Bauman Z. Liquid modernity. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2012.

Adelson SL. & American academy of child and adolescent psychiatry (AACAP) committee on quality issues (CQI): practice parameter on gay, lesbian, or bisexual sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and gender discordance in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:957–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.004.

Byne W, Bradley SJ, Coleman E, Eyler AE, Green R, Menvielle EJ, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Pleak RR, Tompkins DA. Report of the American psychiatric pssociation task force on treatment of gender identity disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(4):759–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9975-x.

Olson-Kennedy J, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Garofalo R, Meyer W, Rosenthal SM. Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:172–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000236.

Dunlop BJ, Coleman SE, Hartley S, Carter LA, Taylor PJ. Self-injury in young bisexual people: a microlongitudinal investigation (SIBL) of thwarted belongingness and self-esteem on non-suicidal self-injury. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2022;52(2):317–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12823.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the help Drs. Alessio Simonetti and Evelina Bernardi provided in statistical issues.

Funding

This work has received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM, LM, AM, CC, and DPRC. conceived the review. EM, LM, AM, CC, and GDK. organized and collected the material and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AM, EM, GDK, DJ, FM, and SC. performed literature searches. EM, LM, AM, CC and GDK. wrote the Methods and decided eligibility criteria. DPRC, GDK. and GS. supervised the writing of the manuscript. DPRC, CV, AM, GDK. and GS. revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplement to Marconi et al. (2023)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Marconi, E., Monti, L., Marfoli, A. et al. A systematic review on gender dysphoria in adolescents and young adults: focus on suicidal and self-harming ideation and behaviours. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 17, 110 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00654-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00654-3