Abstract

Background

Even though child psychopathology assessment guidelines emphasize comprehensive multi-method, multimodal, and multi-informant methodologies, maternal-report symptom-rating scales often serve as the predominant source of information. Research has shown that parental mood symptomatology affects their reports of their offspring’s psychopathology. For example, the depression-distortion hypothesis suggests that maternal depression promotes a negative bias in mothers’ perceptions of their children’s behavioral and emotional problems. We investigated this difference of perception between adoptive mothers and internationally adopted children. Most previous studies suffer from the potential bias caused by the fact that parents and children share genetic risks.

Methods

Data were derived from the Finnish Adoption (FinAdo) survey study (a subsample of adopted children aged between 9 and 12 years, n = 222). The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used to assess emotional and behavioral problems and competences of the adopted children. The CBCL was filled in by the adopted children and the adoptive mothers, respectively. Maternal depressive symptoms were measured using the short version of the General Health Questionnaire.

Results

On average, mothers reported less total CBCL symptoms in their children than the children themselves (0.25 vs 0.38, p-value < 0.01 for difference). Mothers’ depressive symptoms moderated the discrepancy in reporting internalizing symptoms (β = − 0.14 and p-value 0.01 for interaction) and the total symptoms scores (β = − 0.22 and p-value < 0.001 for interaction) and externalizing symptoms in girls in the CBCL.

Limitations

The major limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design and the fact that we only collected data in the form of questionnaires.

Conclusions

The results of our research support the depression-distortion hypothesis concerning the association of maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms in girls in a sample without genetic bias

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the assessment of emotional and behavioral psychiatric symptoms in children, the procedure of collecting and combining information from multiple sources, e.g. mother, father, therapist, teacher, or foster parent, has become the standard of practice [36]. However, research has consistently shown that the agreement between ratings of child behavior by different informants is only low to moderate [14, 19, 34, 47] and considerable discrepancies have also been observed between parent and adolescent reports of adolescent behavior [15]. Furthermore, it has been argued that the nature of discrepancies differs by type of behavior [35].

A number of possible explanations have been given to this discrepancy. The depression-distortion hypothesis suggests that maternal depression promotes a negative bias in mothers’ perceptions of their children’s behavioral and emotional problems [13, 39, 40], with recent evidence indicating that this effect may be greater in questionnaires than in clinical interviews [32]. This hypothesis does not imply that depressed mothers perceive their children in a more negative way, but that their perception is biased. The Attribution Bias Context model (ABC model) suggests that reporting discrepancies may result from discordant perspectives between informants [15, 43]. In support of the ABC model and depression-distortion hypothesis, previous research has demonstrated that parents’ depression and anxiety are associated with over-reporting children’s problem behaviors [15, 20, 23, 46]. However, some research shows that when other variables, such as family functioning, are controlled, the impact of mood on ratings is non-significant or small [16, 49].

It has been argued, that children of psychiatrically ill mothers show more symptomatic behavior than do the children of healthy mothers [10, 37] at least partly due to shared genetic background. Maternal psychopathology appears therefore to be related to actual child psychopathology by means of genetic transmission, social learning processes, lack of maternal sensitivity, insecure attachment patterns or inadequate or inconsistent parenting behavior. Higher maternal ratings may therefore also reflect a truly higher level of mental health symptoms in their children. This alternative assumption has been called the accuracy model [33]. Although the combinatory model suggesting that maternal ratings of child psychiatric symptoms might be influenced simultaneously by pathologic distortions by the mother and by a truly increased level of child psychiatric symptoms may be reasonable, the evaluation of the relative effects of the two are difficult to detect when parents and children share genetic risks.

In this study, we investigated the influence of maternal psychopathology, more precisely depressive symptoms, on the rating of emotional and behavioral problems of their internationally adopted children. We tested the effect of maternal depressive symptoms on the difference between maternal and child ratings. Paternal ratings were excluded, as the number of fathers that filled in the questionnaires was low and the cohort included single mothers as well. Whereas most research on cross-informant agreement or discrepancy focuses on biological offspring, in our sample these mother–child couples are genetically unrelated.

We hypothesized that a discrepancy would also be observed between adoptive mothers and internationally adopted children.

Methods

Participants

This study is part of the ongoing FINnish ADOption (FinAdo) study. The target population of the study consists of all children internationally adopted through three legalized adoption organizations in Finland between 1985 and 2007. The children were identified through official adoption organizations approved by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Data were gathered with questionnaires exploring information about the child, the adoptive family and the parents themselves. The questionnaires were sent to the parents and in the cover letter it was instructed that the child/adolescent fills in their own questionnaires and there was a separate return envelope for the child. The questionnaires were filled in separately by the parents and those adoptees over 9 years of age. The reason for the age of 9 years as the cut-off was the fact that they were the youngest that responded themselves to the questionnaires and thus comparing mothers’ and childs’ ratings was possible only for them and older participants. The average age at the time of estimation was 14.1 for boys and 13.9 for girls.

The surveys were conducted in December 2007, January 2008 and March 2009. The original cohort included 634 boys and 803 girls at study entry, aged from 0 to 18 years (mean 7.5, Sd 4.4). The study sample (n = 222) consisted of 124 girls (55.86%) and 98 boys (44.14%) and their mothers. Fathers were excluded, as the respondents were mainly the mothers. The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Hospital district of Southwest Finland and written and informed consent was obtained from the parents and the children themselves.

Measures

Child-related background factors

A specific questionnaire developed for the FinAdo study was used to gain knowledge about the characteristics of the child before and after adoption. The child-related variables included the child’s gender, age at the time of adoption, which is the same as age at arrival to Finland, and at the time of responding to the questionnaire, continent of birth, the type and number of pre-adoption placements and health history. Maternal SES was defined as the mother’s employment status, which reflects maternal education. Occupational status, although not the most comprehensive measure of SES, is widely used e.g. [29, 31].

Parental depressive symptoms

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) is a self-administered screening questionnaire, designed for use in consulting settings aimed at detecting individuals with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder [21]. The 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) is the most extensively used screening instrument for common mental disorders, in addition to being a more general measure of psychiatric well-being. Various versions of the GHQ-12 have been reported to be useful in determining the presence of depression and also shorter (five item) versions have shown good predictive validity [1]. In this study, we used a five-item questionnaire requesting whether the parent had recently been able to enjoy his/her daily duties, been thinking of himself/herself as a worthless person, felt unhappy and depressed, lost his/her self-confidence, or felt quite happy. The questions were answered on a 4-point scale: 1 = more than usual, 2 = as much as usual, 3 = less than usual, 4 = much less than usual. The first and last items were reverse coded and all items were summed.

The adopted children’s emotional and behavioral problems

The Child Behavior Checklist is a component in the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment developed by Thomas M. Achenbach. It is a 118-question behavioral checklist that is completed by the child’s parent or caretaker. It is an instrument designed to obtain data on children’s behavioral/emotional problems and competencies, and it is widely used in clinical and research settings because of its demonstrated reliability and validity, ease of administration, and applicability to clinical and nonclinical groups [17]. In our study, we chose to use the CBCL to measure behavioral problems because of its wide use as a well-known method in adoption research and its good psychometric reliability [22, 26, 50].

The CBCL provides a total score for behavioral characteristics and separates scores for internalizing and externalizing behavioral symptoms. Internalizing behavioral symptoms reflect problems mainly within the self, such as anxiety, depression, somatic complaints without medical cause, and withdrawal from social contacts. Externalizing behavioral signs include conflict with others and rule-breaking or aggressive behavior [2, 3].

A high level of association between the CBCL and diagnoses derived via structured interviews has been documented. For example, studies have found associations between depressive disorders and the depression/anxiety, withdrawn, and somatic complaints subscales, as well as with the broadband internalizing scale. Similarly, anxiety disorders have been significantly associated with elevated scores on the depression/anxiety subscale. In addition, these studies have found significant associations between conduct disorder and the aggressive behavior, delinquent behavior, and the broadband externalizing subscales of the CBCL [7,8,9, 18, 28, 52].

We used the CBCL for ages 6–18 with 113 questions [22], leaving out the 5 open questions. Each item was rated as (0) not true, (1) somewhat or sometimes true, and (2) very true or often true. The higher the child’s scores in the CBCL, the more behavioral problems the child has.

The CBCL was filled in by the adoptive mothers and the adopted children, respectively.

Statistical analyses

The associations between maternal depressive symptoms which were treated as continuous and the CBCL were analyzed using linear regression models with child CBCL reports as outcomes and mother CBCL reports as predictors. The interaction term between mothers’ depressive symptoms and their CBCL reports was added into the models to test the significance of the difference between with higher depressive symptoms and lower depressive symptoms reporting discrepancy.

All analyses were performed using R 3.6.1, and p values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean level of depressive symptoms in mothers was 1.89 (SD 0.51). The mean score of externalizing symptoms was 0.28 (SD 0.32) for mothers and 0.38 (SD 0.30) for children. For internalizing symptoms, the mean scores were 0.19 (SD 0.20) for mothers and 0.33 (SD 0.28) for children. The mean CBCL total score for mothers was 0.25 (SD 0.24) and for children 0.38 (SD 025). Mothers’ depressive symptoms were not associated with their children’s CBCL symptoms reported by themselves or by their children (Table 2).

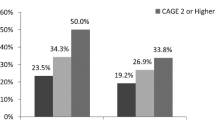

There were significant interaction effects between mothers’ depressive symptoms and mother reported internalizing symptoms (p-values for interaction range from (0.013 to 0.006) (Table 3). The higher the mothers depressive symptoms the less similar the mother and child-reported symptoms were (Fig. 1). Similar interaction effect was found between mothers’ depressive symptoms and mother reported total CBCL score (p-values range for interaction effect range from 0.010 to 0.001) (Table 4; Fig. 2). There were also significant interaction effects between mothers depressive symptoms and mother reported externalizing symptoms (p-values for interaction range from (0.028 to 0.005), but these effects were only evident in girls (third level gender interactions p-value range (0.025–0.011) (Table 5). Again, the more mother had depressive symptoms the less similar the symptom reporting was between the mother and the child (Fig. 3). All these models were adjusted for child’s age, age at arrival to Finland and mother’s SES.

Interaction effect between mothers depressive symptoms (classified as high = + 1 SD, and Low = − 1 SD) and mother-rated internalizing symptoms for child-rated internalizing symptoms (testing modifying effect of mothers depressive symptoms in mother and child-rated similarity in internalizing symptoms)

Interaction effect between mothers depressive symptoms (classified as high = + 1 SD, and Low = − 1 SD) and mother-rated externalizing symptoms for child-rated externalizing symptoms (testing modifying effect of mothers depressive symptoms in mother and child-rated similarity in externalizing symptoms)

Discussion

As in previous studies, our research revealed a discrepancy in reporting emotional problems of children also in this group of adopted children and their parents who have no shared genetic background. Our study showed that maternal depressive symptoms were related with poor agreement on reports for the total CBCL score, internalizing symptoms and for girls for externalizing symptoms too and thus supports the depression-distortion hypothesis.

It has been argued, that the nature of discrepancies differs by type of behavior. Some studies have found that there is higher agreement for externalizing problems, such as delinquent, aggressive, and antisocial behavior, than internalizing problems, such as withdrawal, anxiety and depression [41, 44, 48]. This might be due to the fact that internalizing problems may be harder to observe [27] and externalizing problems may be more obvious, more consistent across situations, or more persistent [48]. Moreover, some researchers have observed that parents tend to report more externalizing problems than adolescents [6, 11], and others, the converse [5, 42] or no difference [24]. Interestingly, some studies have found that parental depression is associated with higher agreement [30, 38] and that parents with psychopathology may be more accurate reporters due to their awareness of and sensitivity to mental health symptoms [25]. It might be argued, that mothers with depressive symptoms could be more accurate in their reports than those without.

Furthermore, Hughes and Gullone state that such discrepancies cannot indicate which informant is more accurate, or whether informants are over- or under-reporting the child’s behavior [25]. Rather, it could be argued that each informant provides unique information reflecting subjective, partial truths based on how and where they observe the behavior [6, 16].

The present study integrates and extends prior research on cross-informant discrepancy by using an adoption design to disentangle the contribution of genetic influences. A comparable study design was used by Tarren-Sweeney et al., who conducted a study on interrater agreement between foster parents and teachers [45]. They concluded that teachers and foster parents demonstrated moderate to good agreement (kappa = 0.70–0.79) in identifying clinically significant total problems and externalizing problems, but poor agreement in identifying internalizing problems. However, their study did not address the potential discrepancy between the children and foster parents. Because of this difference, the two studies are not fully comparable.

The finding that mothers with depressive symptoms and adopted girls report differently on externalizing symptoms is worth noticing. In the general population, females are considered at heightened risk for internalizing symptoms and males for externalizing symptoms. Watson et al. state that in children of depressed parents these normative gender differences may be even more evident, meaning that girls may be at even greater risk for internalizing problems and boys for externalizing problems [51]. Hence, the question arises, whether mothers with depressive symptoms are less tolerant and/or more sensitive to girls’ externalizing symptoms.

Another interesting aspect on parent–child discrepancy is how much and what kind of information it can reflect about the relationship between parents and children, especially in adoptive families. For instance, the question of the relevance of attachment constructs arises. Attachment itself can be considered to be related to the length of time the child has been living with the adoptive family.

Strengths and limitations

The results of our study must be considered in the light of the study’s strengths and its limitations.

The major limitation was the cross-sectional design of our study. A longitudinal study would provide an opportunity to examine the stability and changes in maternal depressive symptoms and reporting of child behavioral problems by parents.

A considerable limitation of our study is the low number (7) of mothers who had depressive symptoms. Also, the mothers did not suffer from clinical depression but only had mild symptoms. It should also be taken into consideration that a number of studies have shown that internationally adopted children have more internalizing symptoms than their non-adopted peers [26].

Furthermore, adoptive parents have a lower threshold for referring their adolescents to treatment than biological parents, indicating that they might be more sensitive to potential problems and perhaps overestimate their occurrence [4]. Adoptive parents may also be more willing to seek help from a mental health professional for their troubled child because they are better educated or have greater economic resources than many non-adoptive parents have or because they have previously interacted with social service providers in the process of adopting. No prenatal information about the children and the life-events they experienced (except for the type and number of placements) before the moment they were adopted was available.

Conclusions

The results of our research support the depression-distortion hypothesis in a study sample of genetically unrelated children and mothers, as maternal depressive symptoms were associated with less similar symptom reporting of child internalizing symptoms and girls’ externalizing symptoms compared to the children themselves.

It may be stated that clinicians and studies assessing children’s psychopathology should take into account parental current mood state. Furthermore, it would be of informative value to determine factors that influence agreement and discrepancies between informants. For instance, differences in parenting stress might be involved, especially when there is concurrent depression.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aalto AM, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Uutela A, Pirkola S. The beck depression inventory and general health questionnaire as measures of depression in the general population: a validation study using the composite international diagnostic interview as the gold standard. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197(1–2):163–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.008.

Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991.

Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The child behavior checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21(8):265–71.

Askeland KG, Hysing M, La Greca AM, Aaro LE, Tell GS, Sivertsen B. Mental health in internationally adopted adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(3):203-213.e1 (S0890-8567(16)31995-5[pii]).

Barker ET, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Hendricks C, Suwalsky JTD. Adolescent-mother agreement about adolescent problem behaviors: direction and predictors of disagreement. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36(7):950–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9164-0.

Berg-Nielsen TS, Vika A, Dahl AA. When adolescents disagree with their mothers: CBCL-YSR discrepancies related to maternal depression and adolescent self-esteem. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(3):207–13.

Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, Moore P, Lelon E. Child behavior checklist findings further support comorbidity between ADHD and major depression in a referred sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(6):734–42 (S0890-8567(09)63908-3[pii]).

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Doyle A, Lehman BK, Kraus I, Perrin J, Tsuang MT. Convergence of the child behavior checklist with structured interview-based psychiatric diagnoses of ADHD children with and without comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34(7):1241–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01785.x.

Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, Mick E, et al. Impact of adversity on functioning and comorbidity in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(11):1495–503 (S0890-8567(09)63969-1[pii]).

Boyle MH, Pickles AR. Influence of maternal depressive symptoms on ratings of childhood behaviour. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25:399–412.

Carlston DL, Ogles BM. Age, gender, and ethnicity effects on parent–child discrepancy using identical item measures. J Child Fam Stud. 2009;18(2):125–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9213-2.

Cumming G. The new statistics: Why and how. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(1):7–29.

Daryanani I, Hamilton JL, Shapero BG, Burke TA, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Differential reporting of adolescent stress as a function of maternal depression history. Cogn Ther Res. 2015;39(2):110–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9654-4.

De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DAG, Burgers DE, Rabinowitz J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(4):858–900. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038498.

De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(4):483–509 (2005-08334-001[pii]).

De Los Reyes A, Youngstrom EA, Swan AJ, Youngstrom JK, Feeny NC, Findling RL. Informant discrepancies in clinical reports of youths and interviewers’ impressions of the reliability of informants. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(5):417–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2011.0011.

Dutra L, Campbell L, Westen D. Quantifying clinical judgment in the assessment of adolescent psychopathology: reliability, validity, and factor structure of the child behavior checklist for clinician report. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(1):65–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10234.

Edelbrock C, Costello AJ. Convergence between statistically derived behavior problem syndromes and child psychiatric diagnoses. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1988;16(2):219–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00913597.

Falt E, Wallby T, Sarkadi A, Salari R, Fabian H. Agreement between mothers’, fathers’, and teachers’ ratings of behavioural and emotional problems in 3–5-year-old children. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11): e0206752. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206752.

Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ, Dishion TJ, Kaufman NK. Depressed mood and maternal report of child behavior problems: another look at the depression-distortion hypothesis. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009;30(2):149–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.001.

Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):139–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700021644.

Hawk B, McCall RB. CBCL behavior problems of post-institutionalized international adoptees. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13(2):199–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0068-x.

Hennigan KM, O’Keefe M, Noether CD, Rinehart DJ, Russell LA. Through a mother’s eyes: sources of bias when mothers with co-occurring disorders assess their children. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(1):87–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-005-9005-z.

Huberty TJ, Austin JK, Harezlak J, Dunn DW, Ambrosius WT. Informant agreement in behavior ratings for children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behavior E&b. 2000;1(6):427–35 (S1525-5050(00)90119-7[pii]).

Hughes EK, Gullone E. Discrepancies between adolescent, mother, and father reports of adolescent internalizing symptom levels and their association with parent symptoms. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(9):978–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20695.

Juffer F, van Ijzendoorn MH. Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2501–15 (293/20/2501[pii]).

Karver MS. Determinants of multiple informant agreement on child and adolescent behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34(2):251–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-9015-6.

Kazdin AE, Heidish IE. Convergence of clinically derived diagnoses and parent checklists among inpatient children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984;12(3):421–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00910657.

Keen C, Hunter JE, Allen EG, Rocheleau C, Waters M, Sherman SL. The association between maternal occupation and down syndrome: a report from the national down syndrome project. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2020;223(1):207–13 (S1438-4639(19)30435-3[pii]).

Klaus NM, Mobilio A, King CA. Parent-adolescent agreement concerning adolescents’ suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div. 2009;38(2):245–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698412.

Lehti V, Hinkka-Yli-Salomaki S, Cheslack-Postava K, Gissler M, Brown AS, Sourander A. Maternal socio-economic status based on occupation and autism spectrum disorders: a national case–control study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(7):523–30. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2015.1011692.

Maoz H, Goldstein T, Goldstein BI, Axelson DA, Fan J, Hickey MB, et al. The effects of parental mood on reports of their children’s psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(10):1111-22.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.005.

Muller JM, Achtergarde S, Furniss T. The influence of maternal psychopathology on ratings of child psychiatric symptoms: an SEM analysis on cross-informant agreement. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(5):241–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-011-0168-2.

Muller JM, Romer G, Achtergarde S. Correction of distortion in distressed mothers’ ratings of their preschool-aged children’s internalizing and externalizing scale score. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(1):170–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.035.

Ordway MR. Depressed mothers as informants on child behavior: methodological issues. Res Nurs Health. 2011;34(6):520–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20463.

Pelham WE Jr, Fabiano GA, Massetti GM. Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div. 2005;34(3):449–76. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_5.

Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, et al. Children of currently depressed mothers: A STAR*D ancillary study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(1):126–36. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n0119.

Reuterskiöld L, Öst L, Ollendick T. Exploring child and parent factors in the diagnostic agreement on the anxiety disorders interview schedule. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2008;30:279–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9081-5.

Richters J, Pellegrini D. Depressed mothers’ judgment about their children: an examination of depression-distortion hypothesis. Child Dev. 1989;50:1068–75 (2805884).

Richters JE. Depressed mothers as informants about their children: a critical review of the evidence for distortion. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(3):485–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.485.

Salbach-Andrae H, Klinkowski N, Lenz K, Lehmkuhl U. Agreement between youth-reported and parent-reported psychopathology in a referred sample. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(3):136–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-0710-z.

Sourander A, Helstela L, Helenius H. Parent-adolescent agreement on emotional and behavioral problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(12):657–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050189.

Splett JW, Raborn A, Brann K, Smith-Millman MK, Halliday C, Weist MD. Between-teacher variance of students’ teacher-rated risk for emotional, behavioral, and adaptive functioning. J Sch Psychol. 2020;80:37–53 (S0022-4405(20)30022-4[pii]).

Stokes J, Pogge D, Wecksell B, Zaccario M. Parent-child discrepancies in report of psychopathology: the contributions of response bias and parenting stress. J Pers Assess. 2011;93(5):527–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.594131.

Tarren-Sweeney MJ, Hazell PL, Carr VJ. Are foster parents reliable informants of children’s behaviour problems? Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(2):167–75.

Treutler CM, Epkins CC. Are discrepancies among child, mother, and father reports on children’s behavior related to parents’ psychological symptoms and aspects of parent-child relationships? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31(1):13–27. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021765114434.

van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, Tiemeier H. Multitrait-multimethod analyses of change of internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence: predicting internalizing and externalizing DSM disorders in adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020;129(4):343–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn000051.

van der Meer M, Dixon A, Rose D. Parent and child agreement on reports of problem behaviour obtained from a screening questionnaire, the SDQ. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(8):491–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-0691-y.

van der Toorn SL, Huizink AC, Utens EM, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Ferdinand RF. Maternal depressive symptoms, and not anxiety symptoms, are associated with positive mother-child reporting discrepancies of internalizing problems in children: a report on the TRAILS study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(4):379–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0062-3.

Verhulst FC, Versluis-den Bieman H, van der Ende J, Berden GF, Sanders-Woudstra JA. Problem behavior in international adoptees: III. Diagnosis of child psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(3):420–8.

Watson KH, Potts J, Hardcastle E, Forehand R, Compas BE. Internalizing and externalizing symptoms in sons and daughters of mothers with a history of depression. J Child Family Stud. 2012;21(4):657–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9518-4.

Weinstein SR, Noam GG, Grimes K, Stone K, Schwab-Stone M. Convergence of DSM-III diagnoses and self-reported symptoms in child and adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(4):627–34 (S0890-8567(09)64650-5[pii]).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the all the internationally adopted children and their parents for the participation in this study. M.E. was supported by the Academy of Finland (265977). K.L. was supported by the Ane and Signe Gyllenberg Foundation and the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation. The study was supported by the Foundation of Pediatric Research, Finland, the Ane and Signe Gyllenberg Foundation and EVO Grant from Turku University Hospital.

Funding

Open access funded by Helsinki University Library. Krista Liskola received a grant of 6000€ from the Ane and Signe Gyllenberg Foundation in 2019, which partly relates to the research reported in this article. The Ane and Sgne Gyllenberg had no role in either the gathering or the interpretation of these data presented in this article. Marko Elovainio was supported by the Academy of Finland (265977). The study was supported by the Foundation of Pediatric Research, Finland, the Ane and Signe Gyllenberg Foundation and EVO Grant from Turku University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ME and HL were responsible of the study concept and design. ME, HL and HR and contributed to the data acquisition. JL and ME performed the statistical analyses. KL provided the first version of the manuscript. ME, HL, HR and JS provided critical revision of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the content and approved the final version of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland, and written and informed consent was obtained from the parents and the children themselves.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have not had any financial support or other relationships that may have caused any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liskola, K., Raaska, H., Lapinleimu, H. et al. The effects of maternal depression on their perception of emotional and behavioral problems of their internationally adopted children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 15, 41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00396-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00396-0