Abstract

Implementation science scholars argue that knowing ‘what works’ in public health is insufficient to change practices, without understanding ‘how’, ‘where’ and ‘why’ something works. In the peer reviewed literature on conflict-affected settings, challenges to produce research, make decisions informed by evidence, or deliver services are documented, but what about the understanding of ‘how’, ‘where’ and ‘why’ changes occur? We explored these questions through a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature based on core dimensions of the Extended Normalization Process Theory. We selected papers that provided data on how something might work (who is involved and how?), where (in what organizational arrangements or contexts?) and why (what was done?). We searched the Global Health, Medline, Embase databases. We screened 2054 abstracts and 128 full texts. We included 22 papers (of which 15 related to mental health interventions) and analysed them thematically. We had the results revised critically by co-authors experienced in operational research in conflict-affected settings. Using an implementation science lens, we found that: (a) implementing actors are often engaged after research is produced to discuss feasibility; (b) new interventions or delivery modalities need to be flexible; (c) disruptions affect how research findings can lead to sustained practices; (d) strong leadership and stable resources are crucial for frontline actors; (e) creating a safe learning space to discuss challenges is difficult; (f) feasibility in such settings needs to be balanced. Lastly, communities and frontline actors need to be engaged as early as possible in the research process. We used our findings to adapt the Extended Normalization Process Theory for operational research in settings affected by conflicts. Other theories used by researchers to document the implementation processes need to be studied further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Conducting operational research in conflict-affected settings is limited by insecurity, inconsistent data, ethical issues, political instabilities, populations movements and fragmented governance [1,2,3,4]. A persisting research gap has been documented in such settings over the past two decades [5,6,7,8]. To fill this gap, efforts have focused on producing more high-quality research [9,10,11,12], recognizing that subsequent decision-making for policy and planning depends on the quality and relevance of the evidence base, on the type of organizational support, and on the level of disruptions [13,14,15,16]. But once operational research is conducted and decisions are made to change policies or plans, does it follow that practices will be adjusted? This assumption is questioned by scholars working on the implementation of evidence-based public health practices in more stable settings [17,18,19,20]. They found that knowing ‘what works’ is not enough; changing practices means considering implementation as a social process, engaging practitioners to learn dynamically, and looking at system complexities [18, 21, 22].

In conflict-affected settings, services delivery is known to be limited by violence, insecurity, logistical constraints, delivery gaps, inflexible funding, weak coordination, and fragmented leadership [23,24,25,26,27]. Understanding how these limitations can be overcome and by whom is unclear. Grasping how empirical results might lead to revised practices is complex in conflict-affected settings [28,29,30]. This paper applied an implementation science lens to analyse how scholars documented this process in the peer-reviewed literature.

Within implementation science, ‘who is involved?’, ‘to do what?’ and ‘where?’ are core questions used to identify implementation mechanisms [19, 20]. We chose the Extended Normalization Process Theory (ENPT) because it focuses on implementing actors’ agency and questions the capacities and the potential of actors [18, 31]. Given recognized power imbalances in humanitarian settings, choosing a framework that accounts for the agency of frontline actors was important [1, 32]. In a previous study we found that using the ENPT allowed one to analyse how actors negotiated constraints collectively [33]. Our results also generated further questions to be assessed in the peer-reviewed literature:

-

(1)

How are implementing actors engaged by researchers to produce knowledge?

-

(2)

Do the characteristics of the intervention matter?

-

(3)

How do contextual and organizational factors influence implementing actors?

-

(4)

What role do implementation actors play?

-

(5)

What does implementing revised practices look like?

-

(6)

How do actors negotiate the implementation process?

In this review we assessed how authors documented how new empirical research results were integrated into routine practices by implementing actors (used interchangeably with frontline actor in this paper) in settings affected by conflict or violence.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the peer-reviewed literature to understand better how scholars documented and understood the process by which empirical research findings lead to revised practices in conflict-affected settings. We based our work on implementation science tools and established criteria to include papers that described the interaction between actors, contexts, and new interventions. The data extraction and analysis were deductive when assessing how intervention characteristics and contextual factors emerged in our data based on known implementation science concepts. An inductive analysis was used to analyse data on the roles that actors played, what implementation looked like and what was negotiated, in order to use our results to adapt the ENPT further. Both steps allowed us to respond to the six questions presented in the background section. The first three questions are based on existing implementation science concepts and were used for the deductive data analysis. Responses to questions four to six were used for our inductive analysis, to adapt and develop the dimensions of the ENPT for operational research in settings affected by conflict.

We narrowed the scope to empirical results that suggested changes (as opposed to usual policies or prevailing practices) to focus on how new knowledge is integrated into practices, given that humanitarian organizations are known to struggle to learn and integrate changes [34, 35]. Excluding interventions known to be effective also aimed to assess how implementing actors relate to knowledge production (in the context, for example, of operational research or embedded research) in conflict affected settings. In included papers we identified ‘how’ specific barriers were overcome and ‘who’ contributed to the change.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible, papers had to (a) consider the actors, the interventions and the contexts, to present data on key dimensions (the context, the actors, the intervention) described by implementation science scholars [18, 20, 30]. In addition, papers had to (b) focus on a public health intervention implemented by a humanitarian organisation; (c) be peer-reviewed; (d) consider new empirical results; (e) occur in settings affected by conflict or political violence; (f) and exclude clinical procedures or military medicine. All study designs were considered, and interventions had to be based on previous research conducted. These criteria were used to assess how changes were initiated from research to humanitarian practice. We focused on conflict-affected settings to explore the combined effect of political violence, population movements, and instability on research to practice processes. We excluded clinical procedures or military medicine because they take place in more controlled environments, whereas our aim was to understand better the challenges of implementing interventions within communities. The quality of the initial research was analysed descriptively. The documentation process was assessed based on criteria for quality implementation research [36]. The search including records in English from year 2000 to November 2021. This 20-year time frame corresponds to the global recognition that humanitarian responses need to be more systematically based on empirical research results [5, 7, 14, 37, 38]. We used specific definitions in this paper (Table 1).

Information sources

Three public health databases were searched: ‘Global Health’, ‘Medline’, and ‘Embase’, using the Ovid interface. The search strategy was built with a senior librarian from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Search terms were combined into three main concepts: ‘Empirical research production, use, or implementation’ AND ‘Evidence-based practices’ AND ‘humanitarian contexts’. This strategy allowed us to include new empirical findings and their use and implementation in practice, in conflict-affected settings based on core implementation concepts. Key words and subject headings were explored for each concept and combined with Boolean operators. Subject headings were adapted to each database. An example of the search strategy and search terms is available (Additional file 1).

Selection process

Abstracts and full-text screening was conducted by EL. Any papers with unclear eligibility were discussed with NSS and MH to reach an agreement.

Data extraction

Informed by core concepts in implementation science, we developed a data extraction table, based on the following questions: What was the study design? What was the intervention? How was knowledge produced? How was the research process organised? What were the characteristics of the intervention? What were the internal organizational structural capacities? How was the external context approached? How was the relationship with humanitarian actors described? How was the relationship with communities approached? What was negotiated?

Data synthesis, and critical analysis by co-authors

The responses to these questions allowed us to analyse how the implementation of new knowledge was documented in papers selected. All themes were identified in the body of each paper using a narrative synthesis [43]. The data were extracted and analyzed by EL and discussed with NS and MH. Once the key results were synthetized, a group of actors involved in framing, sharing, using or discussing operational research results with field teams from MSF, ICRC and Elrha (MLR, VH, DB, RR and CL) provided critical feedback and questioned the results, proposed additional syntheses to be made, or literature to be integrated into the discussion section. That step allowed us to review our results based on the perspective from actors involved in operational research in conflict-affected settings.

Ethics

This research project was approved on 14 December 2021 by the ICRC (2118_Nov DP_DIR 21/00031 CGB/bap), on 21 December 2021 by the LSHTM (Ref.26482) and on 11 April 2022 by Médecins-Sans-Frontières (MSF) (ID 2177).

Results

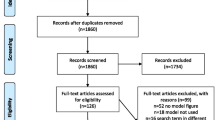

A total of 2054 abstracts were screened. After full-text review, 22 papers met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Table 2 presents a summary of all papers included (n = 22), published between 2011 and 2021. Two-thirds describe the implementation of mental health interventions (n = 15/22). Geographical contexts include 34 countries (Asia (n = 11), the Middle East (n = 4); Africa (n = 13) and South America (n = 6), either experiencing conflicts, affected by conflict, or recovering from conflict or violence.

To build the evidence base for new interventions (by methodology) several authors conducted primary research including household surveys [44,45,46]; qualitative studies [44, 45]; systematic literature reviews [47,48,49]; or retrospective case studies [49]. Authors also referenced existing evidence including WHO guidance [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]; prospective studies [50]; RCTs [54,55,56,57, 61, 62]; randomized trials [63]; surveys [51], operational research [44,45,46, 49, 58, 64, 65]; systematic literature reviews [48, 60,61,62], and literature reviews [47, 50,51,52, 59, 64].

More specifically, the type of expected benefits for each intervention are presented in Table 3. Most authors (n = 14) anticipated a benefit based on external findings from systematic reviews [66, 67], WHO guidance [68,69,70,71,72,73], randomized trials [74, 75], cross-sectional surveys or cohort studies [76,77,78], or a literature review [79]. Other authors either drew from mixed approaches (n = 4) or expect benefits from their own research based on case studies, monitoring results, or qualitative work (n = 4).

To assess and document the implementation of these new interventions, study designs were mostly qualitative (n = 21) (e.g., field team consultations, focus group discussions, ethnographic case studies). Several studies used retrospective records reviews (n = 9) or studied monitoring data (n = 10). One study used a cluster randomised trial and two included a costing analysis. Mostly mixed methods approaches were used to assess the implementation process.

How are implementing actors engaged to produce new knowledge?

Table 4 presents the use of implementing actors’ knowledge, categorized across a continuum of four levels [64, 65, 86]. Most research was described as initiated by external academics [49,50,51,52,53, 56, 57, 61, 64] and later shifted to collaborative strategies [48, 51,52,53,54,55, 58,59,60]. Sometimes implementing actors conducted research [44,45,46,47, 64] but more often were engaged afterwards [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, 58, 59]. Sometimes, the entire continuum was covered across multiple projects [64]; or in different settings and over time [47, 49, 51, 52, 59]. Papers covering less than a one-year time frame and in a restricted number of settings often touched upon a more limited set of components [47, 54, 57, 58, 61, 64, 87].

Do the characteristics of the interventions matter?

Key characteristics of new interventions (focus, flexibility, main user) are described in Table 5. Most papers (n = 15) evaluated a Mental Health and Psychosocial support (MHPSS) intervention. Other interventions (n = 7) related to general service delivery, community health, nutrition, or Maternal and Child Health (MCH). In most cases, implementation meant that the core mechanism of interventions remained unchanged, but modalities such as mobile strategies or packages were adapted. Few papers described an in-depth adaptation of the intervention [44, 45, 64]. The level of flexibility and adaptability were reported as key to successful implementation [44, 47,48,49, 56, 58, 63]. Adapting also meant balancing efficacy or effectiveness with what would be feasible, acceptable, or culturally valid [44, 49, 51,52,53, 55, 58, 62, 63]. For interventions that were less adaptable, such as the clinical provision of Misoprostol [50], or micronutrient powder (MNP) [51,52,53], discussing delivery strategies was essential. When services providers co-produced interventions with researchers, such as scorecards [44], local communities were engaged earlier in the adaptation process.

How do external and organisational factors affect implementing actors?

External factors

External factors created disruptions (Table 6). In order to cope with disrupted social, political, or cultural environments implementing actors adapted continually to instability, violence and changing interests [44, 45, 47, 49, 52, 53, 57,58,59, 61, 62, 64]. Disrupted economies meant that actors constantly negotiated resources [44, 47, 52, 53, 63]. Precarious leadership and weak or unstable policies led to unsteady engagements [52, 54, 55, 57, 64], and difficulties to elaborate longer term plans [44, 45, 52,53,54,55, 59]. Political disruptions meant that research neutrality was questioned, and politicized interests needed to be considered [44, 54]. Limited human resources and irregular access interrupted changes in practices [44, 49, 53,54,55, 57, 59]. Populations sometimes did not trust understaffed or politicized services, and restoring trust was challenging [44, 47, 50, 57, 58]. Security and legal constraints were difficult to solve, limiting access to existing services [44, 50, 62] or the right to work [54, 55, 62].

Organizational factors

Organizational factors were documented as influencing the capacity to implement new practices (Table 7). More specifically, the capacity to increase, recruit or mobilise human resources was crucial [44, 46, 47, 49, 50, 52,53,54,55,56, 59, 60, 62, 63]. Task shifting sometimes allowed implementers to cope with shortages of qualified staff or achieved improved community uptake [53,54,55, 57]. The need for additional training was widely documented [44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 61, 63], while ensuring that newly trained staff had sufficient time for additional tasks [51, 52, 54]. Implementing a change in practice was also influenced by the learning environment. Interactive tools facilitated the link between research and ongoing operations [44, 45, 49, 53]. Sometimes technical committees were set up to discuss implementation processes [45, 47, 49, 51]. When actors interacted frequently with external stakeholders, the process was easier [44, 50, 52,53,54]. Embedding new interventions in existing programs also increased the capacity of actors to implement changes to ongoing practices [44, 45, 48, 49, 52, 63].

What roles do implementation actors play

Implementing actors included national or international services providers or academics (training services providers or adapting interventions) [44, 45, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 64, 65]. Services providers embedded in communities were perceived to be more trusted [47, 48, 50, 56, 58, 63]. Sharing new knowledge mostly consisted in trainings, followed by supervisions and technical support [44, 49,50,51,52, 56,57,58,59, 61,62,63]. Service providers discussed acceptability, cultural validity, acceptability, and negotiated feasibility [47, 49, 52, 56, 58, 63, 64, 89]. They were keen to have intense learning interactions [44,45,46, 64] especially if they had contributed to the design of the research [47, 49, 51,52,53, 58, 59, 64]. Service providers often experienced heavy workloads, facing complex logistical demands, had unmet training needs, and experienced attrition of personnel and incessant turnover [46, 51, 52, 57, 59, 63]. Despite such stressors, they led implementation, identified services users, shaped interventions, and raised community awareness [44,45,46,47, 49,50,51, 56, 58, 65].

Implementing actors also included communities that were affected by violence [49, 55; 61, 63]; disrupted social networks [47, 63]; poverty [46, 54, 55, 61, 63]; lack of access to care [51, 57]; fear of stigma [54, 59]; illiteracy [54, 63] and the lack of awareness of service availability [51, 55, 59]. Supportive communities were a key enabler of revised practices as mediated by acceptability, trust, or intention to adopt [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, 62,63,64,65]. Communities sometimes adapted delivery strategies [44, 45, 47, 58]; used the findings for themselves [46, 64]; produced and managed research findings [46, 64, 65]; or advanced their own rights when political spaces were created [46].

What does the implementation of revised practices look like?

Implementing recommendations in practice involved negotiating acceptability, appropriateness, or adaptations at the level of the community [44, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53, 56, 58, 60, 61, 63,64,65], often collectively [44, 45, 49, 60, 64]. Assessing adoption, adherence, and fidelity was done alongside concern about cost and feasibility [44, 50, 52, 53, 56, 60, 62, 63]. Implementing adapted practices within a health system meant training, technical assistance, supervision, and logistical support [44, 46, 49,50,51,52, 55]. Modifying practices meant getting feedback on progress through existing monitoring tools [49,50,51, 55, 59]. Implementation outcomes included perceived benefit, effectiveness, coverage, and sustainability [44, 49,50,51,52,53, 57, 63] or, being relevant and meeting unmet needs [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 58, 61, 63]. A detailed measure of cost-effectiveness was rare and only two research papers incorporated cost [49, 52]. Measuring costs was challenging because of the complexity of multiple and changing costs over time [52, 53, 59]. The costing studies were often added at the end of the research process, rather than integrated from the start.

How do actors negotiate in the implementation process?

Authors documented a range of tensions that needed to be resolved. First, the roles of researchers, stakeholders, services providers, and communities overlapped to negotiate appropriateness and feasibility [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 62, 63]. Second, research recommendations were adapted following unfounded assumptions about partners or health system capacities [45, 51]; new evidence [45]; political, social or cultural changes [45, 48, 51, 58]; the need to prioritize [51, 59]; and feedback from practice [44, 47, 49, 58, 59]. Specifically, balancing fidelity vs. fit was crucial—this can also be described as efficacy vs. feasibility or core vs. peripheral changes. Trade-offs included dropping fidelity for increased adoption [44, 51, 59]. Field supervisions increased fidelity [51, 56] but raised costs, time, and resources [54, 55, 59]. Third, long term resources were negotiated constantly, through funding mechanisms [52]; prioritization [59]; or integration of health interventions in non-health programs [51,52,53, 87]. Measuring cost-effectiveness was central to sustainability, but was rare, incomplete, or disrupted [52, 59]. Fourth, a balance had to be found between the power of knowledge and the power of practices. Participatory engagements stimulated changes [44,45,46, 64, 65], while top-down accountability mechanisms were inefficient if social, political or practical constraints were ignored [45, 54, 55]. The power of knowledge sometimes was referred to as a cultural capital to challenge existing power structures or foreign research agendas [46, 48]. The power of practices included communities refusing to lose the benefits of a face-to-face consultation [45] or providers asking for different supports [56]. Sometimes researchers pushed back on suggestions to change core mechanisms of action (expected to modify the main mechanisms of the intervention)[58].

Contribution of our results to ENPT

We gathered data on the description of contextual issues, recommendations characteristics, and the roles that actors played. We observed that in conflict-affected settings, frontline actors faced disruptions (financial, human resources, logistics, security, turnover) that needed specific attention. We also found that new interventions were adapted by frontline actors and communities from different cultural, social, or political backgrounds in tense environments. We found that services providers and communities played an important role not only to adapt recommendations but also to compensate for disruptions (such as lack of staff, or irregular funds). Authors documented that frontline actors negotiated resources, adapted interventions and engaged within communities over time, actively, and in all dimensions of the implementation process and these are important manifestations of their agency (Fig. 2).

Carl May’s ENPT (2013) was used as the basis to propose an adapted ENPT (a-ENPT). Findings from the review were used to refine the theory to reflect on the influence of frontline actors and communities described by authors documenting the implementation process in conflict-affected settings.

Discussion

We analysed 22 peer-reviewed papers documenting and providing data on implementation processes in settings affected by conflict published between 2011 and 2021. Whether this 10-year timeframe relates to a concurrent increase in awareness of, and guidance on implementation issues globally, would need further inquiry [36, 90].

In these 22 papers we looked at how the interplay between actors, interventions, and contexts was described and conceived. This study did not aim to consider all implementation barriers for interventions that are known to be cost-effective in such settings. Our objective was to analyse papers providing data on processes described by implementation science scholars, and to explore how shaping new practices based on operational research was understood.

We found that most papers considered interventions focused on mental health, that conflict-affected settings presented specific constraints, and that authors documented that frontline actors and communities played a central role in negotiating revised practices.

Most papers in our review focused on mental health. This could be a consequence of our criteria to select papers providing insights on implementation processes, or because mental health scholars may be more accustomed to engaging with implementation science, given that related communities of practice have developed such tools in more stable settings [91, 92]. The focus on mental health interventions could also be a consequence of the increase in research papers and the burden of mental health in conflict-affected settings [93,94,95]. Despite the focus on mental health, we believe our results have broader utility. Firstly, we considered general characteristics such as adaptability and flexibility. Secondly, engaging implementing actors to negotiate contextual constraints and adapt interventions always mattered. Non-mental health interventions do share such strategies to transform new knowledge into practices. For example, adapting delivery strategies and engaging frontline actors were key to the uptake of MNP or Misoprostol [50,51,52,53].

We also found that conflict affected settings involve specific interactions between actors, interventions, and contexts. Frontline actors were displaced or worked temporarily, which altered how they engaged in implementation. Compared to environmental disasters, implementing actors in settings affected by conflict may suffer from insecurity or distrust researchers [96,97,98,99]. Engaging frontline actors and communities to develop a relevant research question and feasible recommendations is challenging [100, 101]. Disruptive recommendations are hard to integrate when people are displaced, when human resources turnover is widespread and when organizations struggle to maintain continuity. Humanitarian organizations possibly lack technical research skills or are reluctant to be scrutinized in a competitive system [102, 103]. Measuring financial costs also might not reflect the actual economic cost for communities or total program costs for all stakeholders [104, 105]. These factors are difficult to change. But flexible and stepped approaches, balanced partnerships, progressive task-shifting, interactive supervisions, support centres and learning committees, as well as a respectful and trustworthy engagement over time might be useful [36, 103]. These strategies emerge clearly in our results.

We looked at how implementing new practices was documented and conceived. Peer-reviewed literature documents how to better produce new knowledge [2, 7, 8, 106, 107], on how to use results for policies [14, 16, 108,109,110], and on existing barriers to services delivery [4, 25, 111,112,113,114,115,116]. Tools such as the ‘humanitarian lives saved’ or ‘uptake guidance’ facilitate decision-making [117,118,119]. But understanding what these findings and decisions then mean for frontline actors and communities practices in settings affected by conflict, is a yet a different question [15, 103, 120]. Key initiatives reported in the grey literature recognize that supports, trainings, inclusiveness, tailoring research outputs, long term relationships and engaging implementing actors through collective actions are key [103, 119,120,121,122,123,124]. The necessity to address power imbalances and issues of relevance are also observed [102, 103, 124]. Our focus on peer-reviewed papers is based on the argument that peer-review is expected to increase quality, therefore it is a crucial process to establish an evidence base and to document how changes might occur in practice. Our results showed that sharing an understanding of how empirical research results may lead to revised practices in conflict-affected settings is scarce in peer-reviewed literature and may need to be developed further.

Implementation science scholars advance that knowing ‘what works’ alone is not sufficient to bring about changes in practices [19, 20, 30]. The a-ENPT more specifically considers the actors implementing and their potential to engage collectively, which may be crucial in environments where power differentials are known to be exacerbated [1, 32]. In settings affected by conflict, frontline actors and community health workers may build trust, negotiate political sensitivities, or develop sustainable mechanisms [26, 27, 112, 115, 125, 126]. In the set of papers that we analysed, implementing actors reconciled different types of knowledge. The capacity to connect knowledge to practice also echoes the notion of ‘knowledge brokers’ [39, 103, 127]. Such a role might be possible only if there is enough space and time to negotiate at different levels.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this paper is that it offers an in-depth analysis of how authors described and understood how new knowledge may bring changes in practices in conflict-affected settings, using and adapting an existing implementation science tool.

However, this paper carries a number of limitations. First, the screening of abstracts and data extraction was performed by only one person, though this was compensated for by a thorough discussion of the inclusion criteria and early results with two co-authors (NS, MH). Second, included studies were limited to exclusively peer-reviewed papers that provided data on how the actors interact with the context and the intervention to implement revised practices in settings affected by conflict. While this criterion was necessary to collect data related to implementation science concepts, it clearly considerably limited the number and scope of papers included.

This paper focused on peer reviewed literature. However, crucial work has been conducted by organizations such as the World Health Organization or other organizations that is only available in the grey literature [36, 103, 120, 124]. The recognition that the vast majority of the data relevant to the analysis may be situated in grey literature is an important limitation of this paper. Whether grey literature systematically provides a different perspective on mechanisms by which operational research results lead to revised practices in conflict-affected settings would need to be researched further.

Conclusion

Our analysis found that implementation actors may negotiate constraints and revise their practices based on new knowledge in conflict affected settings, provided they have the space and flexibility to do so. This study suggests that implementation science perspectives might be useful in settings affected by conflict. Specifically, implementing new practices based on empirical results is not a linear process, whereby providers and communities are passive recipients after decisions are made. Space for negotiation might be needed to debate and challenge recommendations made. This study showed that when authors reflected on the implementation process, actors from within the community or working close to communities need to be engaged early. How such a negotiation can be framed theoretically, and whether the ENPT is the right tool to do so, needs to be researched further.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ICRC:

-

International Committee of the Red Cross

- IDPs:

-

Internally Displaced Populations

- a-ENPT:

-

Adapted Extended Normalization Process Theory

- ENPT:

-

Extended Normalization Process Theory

- ELRHA:

-

Enhancing Learning and Research in Humanitarian Assistance

- LSHTM:

-

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- MHPSS:

-

Mental Health and Psycho-Social

- MSF-OCB:

-

Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Centre Belgium

- MCH:

-

Mother and Child Health

- MNP:

-

Micronutrient Powder

- NGO:

-

Non-Governmental Organization

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- RCTs:

-

Randomized Controlled Trials

References

El Achi N, Menassa M, Sullivan R, Patel P, Giacaman R, Abu-Sittah GS. Ecology of war, health research and knowledge subjugation: insights from the Middle East and North Africa Region. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86(1):120.

Ager A, Burnham G, Checchi F, Gayer M, Grais RF, Henkens M, et al. Strengthening the evidence base for health programming in humanitarian crises. Science. 2014;345(6202):1290–2.

Ford N, Mills EJ, Zachariah R, Upshur R. Ethics of conducting research in conflict settings. Confl Heal. 2009;3(1):7.

Ataullahjan A, Gaffey MF, Sami S, Singh NS, Tappis H, Black RE, et al. Investigating the delivery of health and nutrition interventions for women and children in conflict settings: a collection of case studies from the BRANCH Consortium. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):29.

Kohrt BA, Mistry AS, Anand N, Beecroft B, Nuwayhid I. Health research in humanitarian crises: an urgent global imperative. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(6):e001870.

Blanchet K, Anita R, Frison S, Warren E, Hossain M, Smith J, et al. Evidence on public health interventions in humanitarian crises. Lancet (Br Edition). 2017;390(10109):2287–96.

Barakat S, Chard M, Jacoby T, Lume W. The composite approach: research design in the context of war and armed conflict. Third World Q. 2002;23:991–1003.

Mistry AS, Kohrt BA, Beecroft B, Anand N, Nuwayhid I. Introduction to collection: confronting the challenges of health research in humanitarian crises. Confl Heal. 2021;15(1):38.

Blanchet K, Allen C, Breckon J, Davies P, Duclos D, Jansen J, Mthiyane H, Clarke M. Research Evidence in the Humanitarian Sector: a practice guide. 2018.

Zachariah R, Harries AD, Ishikawa N, Rieder HL, Bissell K, Laserson K, et al. Operational research in low-income countries: what, why, and how? Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(11):711–7.

Zachariah R, Draquez B. Operational research in non-governmental organisations: necessity or luxury? Public Health Action. 2012;2(2):31.

Kumar AMV, Zachariah R, Satyanarayana S, Reid AJ, Van den Bergh R, Tayler-Smith K, et al. Operational research capacity building using ‘The Union/MSF’ model: adapting as we go along. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:819.

Knox KP, Darcy J. Insufficient evidence? The quality and use of evidence in humanitarian action. ALNAP Study London. 2014.

Bradt DA. Evidence-based decision-making in humanitarian assistance. HPN Network Paper—Humanitarian Practice Network, Overseas Development Institute. 2009; 67:24.

Mayne R, Green D, Guijt I, Walsh M, English R, Cairney P. Using evidence to influence policy: Oxfam’s experience. Palgrave Commun. 2018;4(1):122.

Khalid A, Lavis J, El-Jardali F, Vanstone M. Supporting the use of research evidence in decision-making in crisis zones in low- and middle-income countries: a critical interpretive synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18.

Fixsen D, Blase K, Naoom S, Wallace F. Core implementation components. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19:531–40.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci: IS. 2009;4:50.

Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3):171–81.

Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ: Br Med J. 2013;347:f6753.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327.

Estabrooks PA, Brownson RC, Pronk NP. Dissemination and implementation science for public health professionals: an overview and call to action. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E162.

Izugbara C, Muthuri S, Muuo S, Egesa C, Franchi G, Mcalpine A, et al. ‘They say our work is not halal’: experiences and challenges of refugee community workers involved in gender-based violence prevention and care in Dadaab, Kenya. J Refug Stud. 2018;33(3):521–36.

Mirzazada S, Padhani ZA, Jabeen S, Fatima M, Rizvi A, Ansari U, et al. Impact of conflict on maternal and child health service delivery: a country case study of Afghanistan. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):38.

Ataullahjan A, Gaffey MF, Tounkara M, Diarra S, Doumbia S, Bhutta ZA, et al. C’est vraiment compliqué: a case study on the delivery of maternal and child health and nutrition interventions in the conflict-affected regions of Mali. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):36.

Altare C, Malembaka EB, Tosha M, Hook C, Ba H, Bikoro SM, et al. Health services for women, children and adolescents in conflict affected settings: experience from North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):31.

Sami S, Mayai A, Sheehy G, Lightman N, Boerma T, Wild H, et al. Maternal and child health service delivery in conflict-affected settings: a case study example from Upper Nile and Unity states, South Sudan. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):34.

Shahabuddin ASM, Sharkey AB, Jackson D, Rutter P, Hasman A, Sarker M. Carrying out embedded implementation research in humanitarian settings: a qualitative study in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. PLoS Med. 2020;17(7):e1003148.

Aijaz M, Fixsen D, Schultes M-T, Van Dyke M. Using implementation teams to inform a more effective response to future pandemics. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(3):269–73.

Theobald S, Brandes N, Gyapong M, El-Saharty S, Proctor E, Diaz T, et al. Implementation research: new imperatives and opportunities in global health. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2214–28.

May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. J Implementat Sci. 2013;8(1):18.

Sibai A, Rizk A, Coutts A, Monzer G, Daoud A, Sullivan R, et al. North-South inequities in research collaboration in humanitarian and conflict contexts. Lancet. 2019;394:1597–600.

Leresche E, Hossain M, Rossi R, Truppa C, Barth CA, Mactaggart I, et al. Do we really want to know? The journey to implement empirical research recommendations in the ICRC's responses in Myanmar and Lebanon. Disasters. 2022.

Roberts L, Hofmann CA. Assessing the impact of humanitarian assistance in the health sector. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2004;1:3.

Levine AC. Academics are from Mars, humanitarians are from Venus: finding common ground to improve research during humanitarian emergencies. Clin Trials. 2016;13(1):79–82.

Peters DH, Tran NT, Adam T. Implementation research in health: a practical guide alliance HPSR, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland (2013) 69 pp. 2013 (ISBN 978 92 4 150621 2).

Banatvala N, Zwi AB. Public health and humanitarian interventions: developing the evidence base. BMJ. 2000;321(7253):101–5.

Barakat S, Ellis S. Researching under fire: issues for consideration when collecting data and information in war circumstances, with specific reference to relief and reconstruction projects. Disasters. 1996;20(2):149–56.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology-J Br Sociol Assoc. 2009;43:535–54.

May CR, Mair F, Finch T, MacFarlane A, Dowrick C, Treweek S, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):29.

May C, Finch T, Mair F, Ballini L, Dowrick C, Eccles M, et al. Understanding the implementation of complex interventions in health care: the normalization process model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):148.

Rebecca R. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: data synthesis and analysis. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. 2013; https://cccrg.cochrane.org/.

Bennett S, Mahmood SS, Edward A, Tetui M, Ekirapa-Kiracho E. Strengthening scaling up through learning from implementation: comparing experiences from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(Suppl 2):108.

Paina L, Wilkinson A, Tetui M, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Barman D, Ahmed T, et al. Using theories of change to inform implementation of health systems research and innovation: experiences of future health systems consortium partners in Bangladesh, India and Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(2):109.

Sandvik KB, Lemaitre J. Internally displaced women as knowledge producers and users in humanitarian action: the view from Colombia. Disasters. 2013;37(SUPPL1):S36–50.

Jordans MJD, Tol WA, Komproe IH. Mental health interventions for children in adversity: pilot-testing a research strategy for treatment selection in low-income settings. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(3):456–66.

Bosqui T, Mayya A, Younes L, Baker MC, Annan IM. Disseminating evidence-based research on mental health and coping to adolescents facing adversity in Lebanon: a pilot of a psychoeducational comic book ‘Somoud.’ Conflict Health. 2020;14(1):78.

Jordans MJD, Tol WA, Susanty D, Ntamatumba P, Luitel NP, Komproe IH, et al. Implementation of a mental health care package for children in areas of armed conflict: a case study from Burundi, Indonesia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Sudan. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001371.

Foster AM, Arnott G, Hobstetter M. Community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion: evaluation of a program along the Thailand–Burma border. Contraception. 2017;96(4):242–7.

Vossenaar M, Tumilowicz A, D’Agostino A, Bonvecchio A, Grajeda R, Imanalieva C, et al. Experiences and lessons learned for programme improvement of micronutrient powders interventions. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(1):09.

Reerink I, Namaste SM, Poonawala A, Nyhus Dhillon C, Aburto N, Chaudhery D, et al. Experiences and lessons learned for delivery of micronutrient powders interventions. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13 Suppl 1.

Schauer C, Sunley N, Melgarejo CH, Nyhus Dhillon C, Roca C, Tapia G, et al. Experiences and lessons learned for planning and supply of micronutrient powders interventions. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13 Suppl 1.

Fuhr DC, Acarturk C, Uygun E, McGrath M, Ilkkursun Z, Kaykha S, et al. Pathways towards scaling up Problem Management Plus in Turkey: a theory of change workshop. Confl Health. 2020;14:22.

Fuhr DC, Acarturk C, Sijbrandij M, Brown FL, Jordans MJD, Woodward A, et al. Planning the scale up of brief psychological interventions using theory of change. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):801.

Nemiro A, Van’t Hof E, Constant S. After the randomised controlled trial: implementing problem management plus through humanitarian agencies: three case studies from Ethiopia, Syria and Honduras. Intervention. 2021;19(1):84.

Murray LK, Tol W, Jordans M, Zangana GS, Amin AM, Bolton P, et al. Dissemination and implementation of evidence based, mental health interventions in post conflict, low resource settings. Intervention. 2014;12(Suppl 1):94–112.

Sangraula M, Kohrt BA, Ghimire R, Shrestha P, Luitel NP, Van THE, et al. Development of the mental health cultural adaptation and contextualization for implementation (mhCACI) procedure: a systematic framework to prepare evidence-based psychological interventions for scaling. Global Mental Health. 2021;8:e6.

Jordans MJ, Komproe IH, Tol WA, Susanty D, Vallipuram A, Ntamatumba P, et al. Practice-driven evaluation of a multi-layered psychosocial care package for children in areas of armed conflict. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(3):267–77.

Brown FL, Aoun M, Taha K, Steen F, Hansen P, Bird M, et al. The Cultural and contextual adaptation process of an intervention to reduce psychological distress in young adolescents living in Lebanon. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:212.

Miller KE, Jordans MJD. Determinants of children’s mental health in war-torn settings: translating research into action. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(6):58.

Perera C, Salamanca-Sanabria A, Caballero-Bernal J, Feldman L, Hansen M, Bird M, et al. No implementation without cultural adaptation: a process for culturally adapting low-intensity psychological interventions in humanitarian settings. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):46.

Wieling E, Mehus C, Yumbul C, Mollerherm J, Ertl V, Laura A, et al. Preparing the field for feasibility testing of a parenting intervention for war-affected mothers in Northern Uganda. Fam Process. 2017;56(2):376–92.

Giordano F, Ungar M. Principle-driven program design versus manualized programming in humanitarian settings. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;111:104862.

Kienzler H. mental health system reform in contexts of humanitarian emergencies: toward a theory of “Practice-Based Evidence.” Cult Med Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):636–62.

Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, Li J, Andersson G. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med. 2010;40(12):1943–57.

Gualano MR, Bert F, Martorana M, Voglino G, Andriolo V, Thomas R, et al. The long-term effects of bibliotherapy in depression treatment: systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58:49–58.

Dawson KS, Bryant RA, Harper M, Kuowei Tay A, Rahman A, Schafer A, et al. Problem Management Plus (PM+): a WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention for common mental health problems. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):354–7.

Dawson KS, Watts S, Carswell K, Shehadeh MH, Jordans MJD, Bryant RA, et al. Improving access to evidence-based interventions for young adolescents: early adolescent skills for emotions (EASE). World Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):105–7.

Rahman A, Riaz N, Dawson KS, Usman Hamdani S, Chiumento A, Sijbrandij M, et al. Problem Management Plus (PM+): pilot trial of a WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention in conflict-affected Pakistan. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):182–3.

WHO. Preventing and controlling micronutrient deficiencies in populations affected by an emergency. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nutritionlibrary/preventing-and-controlling-micronutrient-deficiencies-inpopulations-affected-by-an-emergency.pdf?sfvrsn=e17f6dff_2 2007.

Dua T, Barbui C, Clark N, Fleischmann A, Poznyak V, van Ommeren M, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001122.

Keynejad R, Thornicroft G, Spagnolo J. WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2021.

Rahman A, Khan MN, Hamdani SU, Chiumento A, Akhtar P, Nazir H, et al. Effectiveness of a brief group psychological intervention for women in a post-conflict setting in Pakistan: a single-blind, cluster, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1733–44.

Patterson G. The next generation of PMTO models. Behav Ther. 2005;28:27–33.

Singh K, Fong YF, Dong F. A viable alternative to surgical vacuum aspiration: repeated doses of intravaginal misoprostol over 9 hours for medical termination of pregnancies up to eight weeks. BJOG. 2003;110(2):175–80.

Betancourt TS, Salhi C, Buka S, Leaning J, Dunn G, Earls F. Connectedness, social support and internalising emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents displaced by the Chechen conflict. Disasters. 2012;36(4):635–55.

Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, Boxer P, Landau S, Dvir S, Shikaki K, et al. Exposure to political conflict and violence and posttraumatic stress in Middle East youth: protective factors. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2012;41(4):402–16.

Moreno-Ruiz NL, Borgatta L, Yanow S, Kapp N, Wiebe ER, Winikoff B. Alternatives to mifepristone for early medical abortion. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;96(3):212–8.

Epping-Jordan JE, van Ommeren M, Ashour HN, Maramis A, Marini A, Mohanraj A, et al. Beyond the crisis: building back better mental health care in 10 emergency-affected areas using a longer-term perspective. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9:15.

Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow AP, Tol WA. Interventions for children affected by war: an ecological perspective on psychosocial support and mental health care. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):70–91.

Joop TV, De Jong M. Public mental health, traumatic stress and human rights violations in low-income countries. In: De Jong J, editor. Trauma, war, and violence: public mental health in socio-cultural context. Boston: Springer, US; 2002. p. 1–91.

Fairbank JA, Friedman MJ, de Jong J, Green BL, Solomon SD, et al. Intervention options for societies, communities, families, and individuals. In: Green BL, Friedman MJ, de Jong JTVM, Solomon SD, Keane TM, Fairbank JA, et al., editors. Trauma interventions in war and peace: prevention, practice, and policy. Boston: Springer, US; 2003. p. 57–72.

Patel V, Thornicroft G. Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: PLoS Medicine Series. PLoS Med. 2009;6(10):e1000160.

Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):566–79.

Martin S. Co-production of social research: strategies for engaged scholarship. Public Money & Management. 2010;30(4):211–8.

Tol WA, Augustinavicius J, Carswell K, Brown FL, Adaku A, Leku MR, et al. Translation, adaptation, and pilot of a guided self-help intervention to reduce psychological distress in South Sudanese refugees in Uganda. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2018;5: e25.

Sangraula M, Turner EL, Luitel NP, Van’t Hof E, Shrestha P, Ghimire R, et al. Feasibility of Group Problem Management Plus (PM+) to improve mental health and functioning of adults in earthquake-affected communities in Nepal. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e130.

Van THE, Sangraula M, Luitel NP, Turner EL, Marahatta K, Van Ommeren M, et al. Effectiveness of Group Problem Management plus (Group-PM+) for adults affected by humanitarian crises in Nepal: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):343.

WHO, ExpandNet. Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy. WHO Library. 2010.

Chambers D. The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation: enhancing the opportunity for implementation science. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50.

Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(3–4):462–80.

Doocy S, Lyles E, Tappis H. An evidence review of research on health in humanitarian crisis: 2021 update. London: Elrah; 2022.

Nemiro A, Jones T, Tulloch O, Snider L. Advancing and translating knowledge: a systematic inquiry into the 2010–2020 mental health and psychosocial support intervention research evidence base. Global Mental Health. 2022:1–13.

Hoppen TH, Priebe S, Vetter I, Morina N. Global burden of post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression in countries affected by war between 1989 and 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(7).

Mayhew SH, Kyamusugulwa PM, Kihangi Bindu K, Richards P, Kiyungu C, Balabanova D. Responding to the 2018–2020 Ebola virus outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: rethinking humanitarian approaches. Risk Manag Healthcare Policy. 2021;14:1731–47.

Ho LS-y, Ratnayake R, Ansumana R, Brown H. A mixed-methods investigation to understand and improve the scaled-up infection prevention and control in primary care health facilities during the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Sierra Leone. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1603.

Yimer G, Gebreyes W, Havelaar A, Yousuf J, McKune S, Mohammed A, et al. Community engagement and building trust to resolve ethical challenges during humanitarian crises: experience from the CAGED study. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):68.

Foghammar L, Jang S, Kyzy GA, Weiss N, Sullivan KA, Gibson-Fall F, et al. Challenges in researching violence affecting health service delivery in complex security environments. Soc Sci Med. 2016;162:219–26.

Rass E, Lokot M, Brown F, Fuhr D, Kosremelli Asmar M, Smith J, et al. Participation by conflict-affected and forcibly displaced communities in humanitarian healthcare responses: a systematic review. J Migr Health. 2020;1.

Lokot M, Wake C. NGO‐academia research co‐production in humanitarian settings: opportunities and challenges. Disasters. 2022.

Bond. Engaging with research for real impact. The state of research in the INGO sector and ways forward for better practice. London: Bond.

ELRHA. From knowing to doing: evidence use in the humanitarian sector. Elrha learning paper. 2021.

Puett C. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of interventions within a humanitarian organisation. Disasters. 2019;43(3):575–90.

Ansbro E. MSF experiences of providing multidisciplinary primary level NCD care for Syrian refugees and the host population in Jordan: an implementation study guided by the RE-AIM framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:381.

Dijkzeul D, Hilhorst D, Walker P. Introduction: evidence-based action in humanitarian crises. Disasters. 2013;37(SUPPL1):S1–19.

van der Haar G, Heijmans A, Hilhorst D. Interactive research and the construction of knowledge in conflict-affected settings. Disasters. 2013;37(Suppl 1):S20-35.

Darcy J, Stobaugh H, Walker P, Maxwell D. The use of evidence in humanitarian decision making—ACAPS operational learning paper. Feinstein International Center Tufts University. 2013.

Vandekerckhove P, Clarke MJ, De Buck E, Allen C, Kayabu B. Second evidence aid conference: prioritizing evidence in disaster aid. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(6):593–6.

Khalid AF. Approaches to the use of research knowledge in policy and practice during the Syrian refugee crisis. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2017;32(S1):S53–4.

Gaffey MF, Waldman RJ, Blanchet K, Amsalu R, Capobianco E, Ho LS, et al. Delivering health and nutrition interventions for women and children in different conflict contexts: a framework for decision making on what, when, and how. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):543–54.

Ahmed Z, Ataullahjan A, Gaffey MF, Osman M, Umutoni C, Bhutta ZA, et al. Understanding the factors affecting the humanitarian health and nutrition response for women and children in Somalia since 2000: a case study. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):35.

Gaffey MF, Ataullahjan A, Das JK, Mirzazada S, Tounkara M, Dalmar AA, et al. Researching the delivery of health and nutrition interventions for women and children in the context of armed conflict: lessons on research challenges and strategies from BRANCH Consortium case studies of Somalia, Mali, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Conflict Health. 2020;14(69).

Shah S, Munyuzangabo M, Gaffey MF, Kamali M, Jain RP, Als D, et al. Delivering non-communicable disease interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. Special issue: reaching conflict-affected women and children with health and nutrition interventions. 2020;5(Suppl 1).

Ramos Jaraba SM, Quiceno Toro N, Ochoa Sierra M, Ruiz Sánchez L, García Jiménez MA, Salazar-Barrientos MY, et al. Health in conflict and post-conflict settings: reproductive, maternal and child health in Colombia. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):33.

Das JK, Padhani ZA, Jabeen S, Rizvi A, Ansari U, Fatima M, et al. Impact of conflict on maternal and child health service delivery—how and how not: a country case study of conflict affected areas of Pakistan. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):32.

Mellon D. Evaluating evidence aid as a complex, multicomponent knowledge translation intervention. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):25–30.

Chou VB, Stegmuller A, Vaughan K, Spiegel PB. The Humanitarian lives saved tool: an evidence-based approach for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health program planning in humanitarian settings. J Glob Health. 2021;11:03102.

DFID. Research uptake: a guide for DFID-funded research programmes. April 2016.

ELRHA. Uptake and diffusion strategy. http://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ELRHA-Uptake-Diffusion-Strategy-2014-2016.pdf. 2014.

DFID. Research uptake in a humanitarian context: insights on designing and implementing a research uptake strategy summary of a panel discussion. February 2016.

DFID. Promoting innovation and evidence-based approaches to building resilience and responding to humanitarian crises. An overview of DFID's approach. 2014.

SOAR. Approaches to research utilization and capacity strengthening'. Learnings from project SOAR synthesis brief. Washington DC: Population Council. 2021.

Elrha. Research impact case studies. 2023.

Tappis H, Elaraby S, Elnakib S, AlShawafi NAA, BaSaleem H, Al-Gawfi IAS, et al. Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health service delivery during conflict in Yemen: a case study. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):30.

Tyndall JA, Ndiaye K, Weli C, Dejene E, Ume N, Inyang V, et al. The relationship between armed conflict and reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition status and services in northeastern Nigeria: a mixed-methods case study. Confl Heal. 2020;14(1):75.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations 5th Edition (2003): Free Press; 1983.

Acknowledgements

We thank the LSHTM senior Librarian, Russel Burke, for his support to build the search strategy. We thank Dr. Jennifer Leaning, retired Professor of the Practice, Harvard Chan School of Public Health, for her insights in the paper.

Funding

The publication fees of this paper were supported by MSF-Luxembourg. MSF-Luxembourg had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Enrica Leresche had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EL designed the study, collected data, analysed data, presented the result, and led the discussion with all co-authors. NSS and MH contributed to the study design, data analysis, presentation of the results, critical discussion of the results, and reviewed the manuscript. MLR, VH, DB, RR and CL contributed to critically discuss the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research project was approved on 14 December 2021 by the ICRC (2118_Nov DP_DIR 21/00031 CGB/bap), on 21 December 2021 by LSHTM (Ref.26482) and on 11 April 2022 by Médecins-Sans-Frontières Belgium (ID 2177).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. SEARCH strategy (in this case for Embase).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Leresche, E., Hossain, M., De Rubeis, M.L. et al. How is the implementation of empirical research results documented in conflict-affected settings? Findings from a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature. Confl Health 17, 39 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00534-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00534-9