Abstract

Background

Regional block, such as thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB), or serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) has been recommended to reduce postoperative opioid use in recent guidelines, but the optimal options for intraoperative opioid minimization remain unclear. The aim of this study was to evaluate the intraoperative opioids-sparing effects of three regional blocks (TEA, TPVB, and SAPB) in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATs).

Methods

This was a retrospective study of the adults undergoing VATs at a tertiary medical center between January 2020 and February 2022. According to the type of regional block used, patients were classified into 4 groups: GA group (general anesthesia without any regional block), TEA group (general anesthesia combined with TEA), TPVB group (general anesthesia combined with TPVB), and SAPB group (general anesthesia combined with SAPB). Cases were matched with a 1:1:1:1 ratio for analysis by age, sex, ASA physical status, and operation duration. The primary outcome was the total intraoperative opioid consumption standardized to Oral Morphine Equivalents (OME). Multivariable linear regression was used to estimate the association of the three regional blocks with the OME.

Results

A total of 2159 cases met the eligibility criteria. After matching, 168 cases (42 in each group) were included in analysis. Compared with GA without any reginal block, the use of TEA, TPVB, and SAPB reduced the median of intraoperative OME by 78.45 mg (95% confidence interval [CI], -141.34 to -15.56; P = 0.014), 94.92 mg (95% CI, -154.48 to -35.36; P = 0.020), and 11.47 mg (95% CI, -72.07 to 49.14; P = 0.711), respectively.

Conclusions

The use of TEA or TPVB was associated with an intraoperative opioid-sparing effect in adults undergoing VATs, whereas the intraoperative opioid-sparing effect of SAPB was not yet clear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the popularization of high resolution CT, more lung nodules and cancers are identified with the incidental screening or evaluation on lung disease [1]. Considering the high mortality of cancer worldwide [2, 3], surgical resection is still one of the main options for suspected malignant nodules [1, 4]. Due to the strong stimulation of thoracotomy, patients undergoing thoracic surgery generally received higher doses of opioids than those undergoing abdominal, urology, gynecology, head, or neck surgeries [5]. Minimal invasive video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATs) reduces the pain of surgery to a certain extent, but still 38% of patients experience moderate to severe pain after VATs [6].

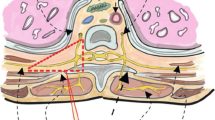

Excessive opioids for intraoperative analgesia will induce acute opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia [7], as well as postoperative hypoventilation, nausea and vomiting, constipation, and urinary retention, those complications can increase hospital stay by 3 days and overall costs by 27% [8,9,10,11]. For these reasons, minimization of opioid usage is a key pillar of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in patients undergoing VATs [2, 12, 13]. Previous studies have shown that compared patients without regional blocks, the thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA), thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB), or serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) could reduce opioids consumption after VATs by depositing local anesthesia in the potential space of the epidural, paravertebral, or interfascial planes, respectively [11, 14, 15]. Several studies compared the perioperative opioid-sparing effect of TEA, TPVB, and SAPB in VATs, but the conclusions were uncertain due to the high heterogeneity of analgesic regimens among studies [5, 16, 17]. Therefore, more evidence for intraoperative opioids-sparing effect of the three regional blocks is needed.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the intraoperative opioid-sparing effect of TEA, TPVB, or SAPB, compared with controls during VATs. We hypothesized that general anesthesia combined with TEA, TPVB, or SAPB could reduce the opioids consumption in patients during VATs compared to general anesthesia without any regional block.

Study design and participants

This study incorporated with a single-center retrospective cohort design. We extracted electronic anesthesia records of eligible patients between January 2020 and February 2022 at Beijing Chaoyang Hospital of Capital Medical University. Patients receiving VATs under general anesthesia with a bronchial intubation were included. A 3 cm and a 1 cm incision were made at the level of the anterior axillary line between the fourth and fifth ribs, and at the level of the midaxillary line between the eighth and ninth ribs, respectively. Those who was younger than 18 years old, experienced emergency surgery, surgery cancellation, intraoperative thoracotomy, severe intraoperative complications (ClassIntra grade > III) [18], or without intraoperative anesthesia information were excluded. Patients who received regional block after skin incision or other regional blocks than TEA, TPVB, or SAPB were also excluded from this study.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Chao-Yang hospital with a waiver of written consent (NO. 2021 − 689) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the STROBE guideline [19].

Procedures and measurements

The demographic characteristics, surgical and anesthetic data, perioperative medications, post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) duration, and length of postoperative hospital stay were obtained from the electronic medical records and reviewed by researchers manually. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, benign or malignant tumor, and medical history. Surgical and anesthetic data referred to the type of surgery, professional title (consultant, associate consultant, registrar) of the surgeon and anesthesiologist with experience in regional blocks, volume of blood loss, duration of surgery (time from incision to end of suture) and anesthesia (time from anesthesia induction to extubation), method of the maintenance of general anesthesia (total intravenous anesthesia [TIVA] or balanced anesthesia), type of regional block combined. Intraoperative medications of interest included opioids, sedatives, muscle relaxants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and regional anesthetics used in the operating room. The clinical practices for opioid use at this facility are as follows: sufentanil 0.2–0.3 ug/kg during induction, followed by continuous intravenous infusion of remifentanil 0.1–0.2 ug/kg/min depending on the patient’s hemodynamic response to surgical stimulation. After surgery, a multimodal analgesia regimen was implemented for all patients and no opioids are administered intraoperatively through patient control analgesia. Patients received a continuous intravenous analgesia (sufentanil 1.5ug/kg in 100 ml, a rate of 2 ml/h) for postoperative analgesia; Patients with thoracic epidural puncture catheter received continuous epidural analgesia (sufentanil 1ug/kg and ropivacaine 200 mg in 200 ml, a rate of 6 ml/h) for postoperative analgesia. In addition, all patients received oral ibuprofen (0.2 g per 8 h) until 48 h. Rescue analgesic was given when patients needed. The time-to-first rescue analgesic within 72 h after the VATs, and postoperative cardiopulmonary-related complications in hospital were also collected from electronic medical records.

According to the type of regional block applied before incision, patients were classified into the following 4 groups, (1) GA group, in which patients received general anesthesia without any regional block; (2) TEA group, in which patients received general anesthesia combined with thoracic epidural analgesia; (3) TPVB group, in which patients received general anesthesia combined with a single thoracic paravertebral block; (4) SAPB group, in which patients received general anesthesia combined with a single serratus anterior plane block. After a preliminary analysis of the entire cohort, it was found that the cases receiving TEA (n = 265), TPVB (n = 222), and SAPB (n = 99) were significantly lower than in the GA group (n = 1252). Additionally, there were statistically significant differences in ASA physical status (P = 0.028) and surgery duration (P < 0.001) between the groups. Then, cases were matched among 4 groups in 1:1:1:1 ratio based on age (± 2 years), sex, ASA physical status, and duration of surgery (± 15 min) for analysis.

The primary outcome was the total opioids consumption (standardized as oral morphine equivalents [OME]) during VATs in operating room [20]. The opioids available in this institution were sufentanil, remifentanil, and tramadol.

Secondary outcomes included: (1) time-to-first rescue analgesic within 72 h after VATs. The rescue analgesics was defined as additional opioids or NSAIDs required; (2) PACU duration. Patients were admitted to the PACU after extubation and were discharged until the Aldrete score reached 10; [21] (3) length of postoperative hospital stay, defined as from end of surgery to discharge from hospital in days. (4) incidence of postoperative complications, defined as cardiopulmonary-related complications graded as I or more according to the Clavien-Dindo score [22] during hospitalization.

Statistical methods

All variables were summarized by descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were expressed as medians (quartiles), and overall comparisons among groups were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test among groups. Categorical variables were expressed as the number of cases (percentage), and the overall comparison among groups was performed using the Chi-square test, if the count in a cell was < 5, then the Fisher’s exact test was used.

For the intraoperative OME, the overall difference among the 4 groups (GA, TEA, TPVB, and SAPB) was determined by Kruskal-Wallis H test. Multiple pairwise comparisons among groups were further performed, and the Bonferroni method was used for correction [23]. Finally, generalized linear regression was used to assess the opioid-sparing effect adjusting for age, sex, weight, TIVA, steroids, NSAIDs [5], and unbalanced variables (P < 0.1).

The time-to-first recue analgesic among 4 groups were presented by Kaplan-Meier curve, and overall statistical significance was analyzed using log-rank test. For secondary outcomes that were statistically different in the overall comparison, a further analysis was done by regression models adjusted for confounding factors and unbalanced variables (P < 0.1).

Power analysis showed that at least 26 patients in each group (no less than 104 patients in total) were required to have 90% power to identify the regional block group with a 20% mean reduction in intraoperative OME, assuming α = 0.05, the standard deviation of OME in the control group was 20% of the mean. To satisfy the requirement that the number of subjects for each variable in the regression analysis should not be less than 10, we included a sample size large enough to accommodate an additional sample in the multivariate regression model. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 24.0 and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 2159 cases met the inclusion criteria. Among them, 1252 cases (57.9%) didn?t receive any regional block, 265 cases (12.3%) received TEA (7 cases failed), 222 cases (10.3%) received TPVB, and 99 cases (4.6%) received SAPB. Forty-two cases in each group were matched for analysis. See Figure 1.

Of the 168 cases included in final analysis, the median [interquartile range] age was 61 [55, 66] years, 104 (61.9%) were female, most (85.7%) were ASA physical status II, 127 (75.6%) had malignant lung tumors. The demographic and surgical characteristics of the patients were comparable among the groups. See Tables 1 and 2. The surgical and anesthetic characteristics were comparable among the four groups except for the percentage of consultant anesthesiologist (14.3 vs. 42.9 vs. 14.3 vs. 0.0%, P < 0.001), percentage of TIVA (85.7 vs. 69.0 vs. 59.5 vs. 19.0%, P < 0.001), the dosage of propofol used during surgery (790 vs. 560 vs. 550 vs. 370 mg, P < 0.001), and the percentage of intraoperative flurbiprofen use (64.3 vs. 21.4 vs. 42.9 vs. 28.6%, P < 0.001). See Table 2.

The primary outcome, the total intraoperative OME, was significantly different among the four groups (median: 512 vs. 411 vs. 384 vs. 461 mg; P = 0.001). Since we further performed 6 pairwise comparisons between groups, the P value was adjusted by Bonferroni correction. Compared with the GA group, the median OME was lower in the TEA group (512 vs. 411 mg, Bonferroni adjusted P = 0.022) and TPVB group (512 vs. 384 mg; Bonferroni adjusted P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the median OME between SAPB and GA group (512 vs. 461 mg; Bonferroni adjusted P = 0.168). See Table 3.

Multivariable analysis identified the adjusted opioid-sparing effect of regional blocks. See Table 4. Compared with GA, TEA reduced intraoperative OME by 78.45 mg (95%CI, -141.34 to -15.56; P = 0.014), TPVB reduced intraoperative OME by 94.92 mg (95%CI, -154.48 to -35.36; P = 0.020), while SAPB group did not significantly reduce intraoperative OME (-11.47 mg, 95CI%, -72.07 to 49.14; P = 0.711)

There was no overall significant difference in the time-to-first rescue analgesia within 72 h after VATs among the 4 groups (P = 0.065). See Supplementary Fig. 1. Compared with the GA group, the median PACU duration in TPVB was decreased by 14.71 min (95% CI, -23.18 to -6.25; P = 0.001), while the use of TEA or SAPB had no significant effect on PACU duration in multivariate analysis. See Supplementary Table (1) Compared with GA, the length of postoperative hospital stay in the SAPB group was decreased by 1.28 days (95% CI, -2.21 to -0.35, P = 0.007). See Supplementary Table (2) No significant difference was observed in the incidence of postoperative complications among the groups. See Table 3.

Disscussion

This retrospective study showed that compared with GA, the use of TEA or TPVB was associated with an intraoperative opioid-sparing effect in patients undergoing VATs. While no significant intraoperative opioid-sparing effect was observed with SAPB.

We observed that compared with GA, TEA reduced the median intraoperative OME by 15.3%, which was lower than those in previous studies (27%\(\sim\)46%) [11, 24]. The reason may be that more patients in our study underwent a less invasive wedge resection, and we did not give any opioids through thoracic epidural catheter intraoperatively. Ultrasound-guided regional block techniques, such as TPVB and SAPB, have been popularized for the high success rate and good safety in postoperative analgesia after VATs [13, 25]. Our results showed that compared with GA, TPVB reduced the median intraoperative OME by 18.5%. The intraoperative opioid-sparing effect of TPVB was comparable to that of TEA in VATs, this is consistent with the results of some randomized controlled studies [26, 27]. SAPB, a novel regional block of interest, was shown to be noninferior to TPVB for 48 h postoperative opioids consumption after VATs [25, 28]. Our data did not observe a significant intraoperative opioid-sparing effect of SAPB in patients undergoing VATs. Similarly, a meta-analysis included 171 patients undergoing VATs also didn’t find a significant intraoperative opioid sparing-effect of SAPB [16]. This may be due to the inability of SAPB to modulate the nociceptive triggers generated by deep visceral stimulation during surgery, and the analgesic effect of SAPB requires the diffusion of local anesthetic in the fascia space over a period of time [16]. Recent network meta-analysis compared the analgesic effect of TEA, TPVB, SAPB, erector spinae plane block (ESPB), and intercostal nerve block, and concluded that TEA, TPVB, and ESPB had better analgesia then others [29].

TEA has been the gold standard for postoperative analgesia after thoracic surgery for decades [12, 13]. Current guidelines more recommend TPVB as an alternative to TEA for the following reasons [26, 30]. First, the analgesic effect (assessed by the pain score at rest or coughing within 48 h after surgery) of TPVB is comparable to that of TEA in patients under multimodal analgesia regimens after VATs [17, 31]. Second, TEA delivers the anesthetic to the epidural space, while TPVB delivers the anesthetic only to the unilateral thoracic paravertebral space with less impact on spinal cord function. This may explain why TPVB showed a lower side-effect profile than TEA, including hypotension, nausea and vomiting, pruritis, and urinary retention after thoracotomy [10, 11, 17, 31, 32]. In addition, due to the extreme caudal angulation of the thoracic spinous processes [11], the TEA is tough and time-consuming with potential risks of arachnoid puncture and spinal cord injury. While, with the introduction of ultrasound, the TPVB becomes simple, and the failure rate as well as the risk of pneumothorax have been reduced [31].

An excellent postoperative pain management is important for early postoperative mobility, reduce postoperative complications, and shorten hospital stay [12, 13]. Regional blocks were believed to be potential to promote early mobilization in patients after VATs since it could reduce the incidence of moderate to severe pain in the early postoperative period [10, 11, 28, 33]. It was reported that the use of regional block reduced postoperative opioid consumption and prolonged the time-to-first rescue analgesic in patients after VATs compared with those who did not receive regional blocks [14, 24, 33, 34]. Recent studies compared the analgesic effects of TEA, TPVB, and SAPB in patients after VATs and found that they were comparable in terms of opioid-sparing effects and postoperative pain scores [17, 24, 25, 28, 30, 32]. Our study did not show that the choice of regional block was associated with prolonged time-to-first rescue analgesic. The reason may be that with an effective multimodal analgesia for VATs, the difference in the time-to-first rescue analgesic among groups was not significant. We did not observe the postoperative pain scores or opioids consumption due to incomplete medical records and a continuous analgesic pump without patient control used after surgery. We observed that compared with GA, TPVB shortened the median PACU duration by 15 min, while SAPB reduced median length of hospital stay by 1 day. Er, et al. reported that compared with GA, SAPB was associated with shorter hospital stay, as it was associated with improved quality of recovery scores by reducing early postoperative pain scores [33]. Nevertheless, the reduction in length of PACU or hospital stay observed in our study did not seem to be encouraging enough for clinical practice. As to the postoperative complications, we could not draw any conclusion due to small sample size.

For further opioid reduction, an opioid-free anesthesia regimens consisting of regional blocks combined with non-opioid analgesics, have been successful applied in patients undergoing VATs recently [35, 36]. The novel regimens showed a comparable pain control intraoperatively (assessed by electroencephalogram) [36] and lower opioids consumption postoperatively compared with standard anesthesia [35]. It is still unclear that whether there will be a relationship between opioid-free anesthesia and early recovery quality in patients after VATs [35, 36], further well-designed randomized controlled trails are warranted.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the intraoperative opioid-sparing effect of TEA, TPVB, and SAPB under multimodal analgesia regimens in patients undergoing VATs. However, this study has several limitations. First, to ensure that there were no major changes in clinical practice, only two years’ data in a single institution were extracted. Although this might result in small sample size, the available cases collected still met the minimum requirements for testing the primary outcome. Second, anesthesiologists might have preferences in implementing analgesic regimens, and the subtle heterogeneity among practitioners still inevitable [17]. Therefore, we collected the title of anesthesiologists for analysis to make the conclusions relatively generally applicable. Third, the main purpose of multimodal analgesia is to minimize opioid use and promote early recovery in patients undergoing VATs. However, due to the property of the retrospective study, the choice of rescue analgesics and the time of discharge may be subjectively determined by the surgeons, which would bias the results. For the same reason, although we matched patients for important factors and further adjusted for imbalance factors to verify the robustness of the conclusion, some unknown risk factors could not be adjusted. Finally, the intraoperative opioid administration was determined by the discretion of the anesthesiologist according to hemodynamic parameters, this may provide the benefit of eliminating the Hawthorne effect for the opioid consumption during operation.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that compared with GA, the use of TEA or TPVB provide an opioid-sparing effect in adult patients undergoing VATs, whereas the opioid-sparing effect of SAPB is not yet clear. Regional blocks have the potential to facilitate postoperative recovery time both in PACU or discharge, albeit this benefit may not be clinically significant in our study. Our findings in concert with recent guideline suggest that the use of regional block reduced opioid consumption intraoperatively, and should be considered as part of an optimal analgesic strategy for patients undergoing VATs. Further randomized control trial is required to explore the optimal regional-block based multimodal analgesia regimens for opioid-free anesthesia in patients undergoing VATs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TEA:

-

Thoracic Epidural Analgesia

- TPVB:

-

Thoracic Paravertebral Block

- SAPB:

-

Serratus Anterior Plane Block

- VATs:

-

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

- GA:

-

General Anesthesia

- OME:

-

Oral Morphine Equivalents

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- ERAS:

-

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery

- PACU:

-

Post-Anesthesia Care Unit

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- TIVA:

-

Total Intravenous Anesthesia

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- ESPB:

-

Erector Spinae Plane Block

References

Mazzone PJ, Gould MK, Arenberg DA, et al. Management of lung nodules and Lung Cancer Screening during the COVID-19 pandemic: CHEST Expert Panel Report[J]. Chest. 2020;158(1):406–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.020.

Rosen DR, Wolfe RC, Damle A, et al. Thoracic epidural analgesia: does it enhance recovery?[J]. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(12):1403–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001226.

Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1145–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1.

Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines[J]. Chest, 2013, 143(5 Suppl): e93S-e120S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2351.

Naik BI, Kuck K, Saager L, et al. Practice patterns and variability in intraoperative opioid utilization: a Report from the Multicenter Perioperative outcomes Group[J]. Anesth Analg. 2022;134(1):8–17. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005663.

Bendixen M, Jorgensen OD, Kronborg C, et al. Postoperative pain and quality of life after lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or anterolateral thoracotomy for early stage lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):836–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00173-X.

Colvin LA, Bull F, Hales TG. Perioperative opioid analgesia-when is enough too much? A review of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia[J]. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1558–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30430-1.

Oderda GM, Gan TJ, Johnson BH, et al. Effect of opioid-related adverse events on outcomes in selected surgical patients[J]. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2013;27(1):62–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2012.751956.

Levy N, Quinlan J, El-Boghdadly K, et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on the prevention of opioid-related harm in adult surgical patients[J]. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(4):520–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15262.

Zhang W, Cong X, Zhang L, et al. Effects of thoracic nerve block on perioperative lung injury, immune function, and recovery after thoracic surgery[J]. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(3):e38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.38.

Xu ZZ, Li HJ, Li MH, et al. Epidural anesthesia-analgesia and recurrence-free survival after Lung Cancer surgery: a randomized Trial[J]. Anesthesiology. 2021;135(3):419–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003873.

Feray S, Lubach J, Joshi GP, et al. PROSPECT guidelines for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations[J]. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(3):311–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15609.

Batchelor TJP, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS(R)) Society and the European Society of thoracic surgeons (ESTS)[J]. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55(1):91–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezy301.

Komatsu T, Kino A, Inoue M, et al. Paravertebral block for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: analgesic effectiveness and role in fast-track surgery[J]. Int J Surg. 2014;12(9):936–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.272.

Park MH, Kim JA, Ahn HJ, et al. A randomised trial of serratus anterior plane block for analgesia after thoracoscopic surgery[J]. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(10):1260–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14424.

De Cassai A, Boscolo A, Zarantonello F, et al. Serratus anterior plane block for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials[J]. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38(2):106–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000001290.

Yeung JH, Gates S, Naidu BV, et al. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009121. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009121.pub2.

Dell-Kuster S, Gomes NV, Gawria L, et al. Prospective validation of classification of intraoperative adverse events (ClassIntra): international, multicentre cohort study[J]. BMJ. 2020;370:m2917. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2917.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies[J]. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X.

Calculation of Oral Morphine Equivalents (OME)[EB/OL]. https://pain.ucsf.edu/opioid-analgesics/calculation-oral-morphine-equivalents-ome.[ Last accessed on 2022 July 29].

Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited[J]. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7(1):89–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/0952-8180(94)00001-k.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey[J]. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae.

Sedgwick P. Multiple hypothesis testing and Bonferroni’s correction[J]. BMJ. 2014;349:g6284. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6284.

Haager B, Schmid D, Eschbach J, et al. Regional versus systemic analgesia in video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: a retrospective analysis[J]. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019;19(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-019-0851-2.

Qiu Y, Wu J, Huang Q, et al. Acute pain after serratus anterior plane or thoracic paravertebral blocks for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a noninferiority randomised trial[J]. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38(Suppl 2):S97–105. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000001450.

Huang QW, Li JB, Huang Y, et al. A comparison of Analgesia after a thoracoscopic Lung Cancer Operation with a sustained Epidural Block and a sustained Paravertebral Block: a randomized controlled Study[J]. Adv Ther. 2020;37(9):4000–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01446-3.

Ding W, Chen Y, Li D, et al. Investigation of single-dose thoracic paravertebral analgesia for postoperative pain control after thoracoscopic lobectomy - A randomized controlled trial[J]. Int J Surg. 2018;57:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.07.006.

Hanley C, Wall T, Bukowska I, et al. Ultrasound-guided continuous deep serratus anterior plane block versus continuous thoracic paravertebral block for perioperative analgesia in videoscopic-assisted thoracic surgery[J]. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(4):828–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1533.

Lin J, Liao Y, Gong C, et al. Regional Analgesia in Video-assisted thoracic surgery: a bayesian network Meta-Analysis[J]. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:842332. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.842332.

Yeap YL, Wolfe JW, Backfish-White KM, et al. Randomized prospective study evaluating single-injection Paravertebral Block, Paravertebral Catheter, and thoracic epidural catheter for postoperative Regional Analgesia after Video-assisted thoracoscopic Surgery[J]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(7):1870–6. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2020.01.036.

Davies RG, Myles PS, Graham JM. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and side-effects of paravertebral vs epidural blockade for thoracotomy–a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials[J]. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(4):418–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/ael020.

Okajima H, Tanaka O, Ushio M, et al. Ultrasound-guided continuous thoracic paravertebral block provides comparable analgesia and fewer episodes of hypotension than continuous epidural block after lung surgery[J]. J Anesth. 2015;29(3):373–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-014-1947-y.

Er J, Xia J, Gao R, et al. A randomized clinical trial: optimal strategies of paravertebral nerve block combined with general anesthesia for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing lobectomy: a comparison of the effects of different approaches for serratus anterior plane block[J]. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(11):11464–72. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2597.

Yuan Z, Liu J, Jiao K, et al. Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block improve opioid-sparing perioperative analgesia in pediatric patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung lesion resection: a prospective randomized controlled trial[J]. Transl Pediatr. 2022;11(5):706–14. https://doi.org/10.21037/tp-22-118.

Selim J, Jarlier X, Clavier T, et al. Impact of opioid-free anesthesia after video-assisted thoracic surgery: a propensity score study[J]. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.09.014.

An G, Zhang Y, Chen N, et al. Opioid-free anesthesia compared to opioid anesthesia for lung cancer patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled study[J]. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0257279. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257279.

Acknowledgements

All the thoracic surgeons and nurses, anesthesiologists from Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, thanks for their insights and the quality of the data collected over time.

Funding

Supported by Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research, 2022-2Z-2039).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YX: helped design the study, collect the data, analyze the data, and prepare the manuscript. LC: helped collect the data, analyze the data, and prepare the manuscript. JJ: helped design the study, and prepare the manuscript. FYL: helped design the study, collect the data, and prepare the manuscript. WCW: helped design the study, and conceptualize the work. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Chao-Yang hospital with a waiver of written consent (NO. 2021 − 689), and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the STROBE guideline.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, Y., Chen, L., Jia, J. et al. The association of regional block with intraoperative opioid consumption in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a single-center, retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg 19, 124 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02611-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02611-3