Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the prognostic significance of surgery in large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNC) patients.

Methods

A total of 453 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database diagnosed with stage T1-4N0-2M0 LCNC from 2010 to 2015 were analyzed. The propensity-score matching analysis with a ratio of 1:1 was used to minimize the bias effect of other clinical characteristics, and 77 pairs of patients’ data were performed for subsequent statistical analysis. The Cox proportional hazards model, Kaplan-Meier analysis, and Log-rank test were used in the present study. The primary observational endpoint was cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Results

The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year CSS rates were 60.0%, 45.0%, and 42.0% in those 453 LCNC patients. Compared with patients who underwent surgical resection, patients without surgery had a lower 5-year CSS rate (18.0% vs. 52.0%, P < 0.001). After analyses of multivariable Cox regression, chemotherapy, T stage, N stage, and surgery were identified as independent prognostic indicators (all P < 0.05). In the cohort of old patients, the median survival time was longer in cases after surgery than those without surgery (13.0 months vs. NA, P < 0.001). Besides, in patients with different clinical characteristics, the receiving surgery was a protective prognostic factor (all hazard ratio < 1, all P < 0.05). In addition, for the cohort with stage T1-2N0-2M0, patients after the operation had more improved outcomes than patients without surgery (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

We proposed that the surgery could improve the survival outcomes of LCNC patients with stage T1-4N0-2M0. Moreover, old patients could benefit from surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although lung cancer has shown a decline in incidence worldwide in recent years, its mortality rate remains at the top of the malignant disease spectrum [1]. Among lung cancers, neuroendocrine carcinoma is not a common pathological type, mainly including small-cell carcinoma, combined small-cell carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, and large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNC) [2, 3]. As for LCNC, its treatment is now considered to be closer to that of small-cell carcinoma [4]. Surgical resection has been shown to be effective for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer, but the role of surgery for large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma still needs further clarification [5, 6].

Old age is a risk factor for prognoses of malignancies, confirmed by other studies [6,7,8,9]. Besides, previous reports showed that the rate of perioperative complications in old patients was higher than in young patients [10, 11]. Therefore, exploring the significance of receiving surgery in old patients is valuable. However, the study on illuminating the association between surgery and old LCNC patients is currently lacking. Thus, this study aimed to uncover surgery’s role in the LCNC and old patients.

Methods

Patients

The ethics committee of The Affiliated People’s Hospital of Ningbo University approved this study and considered this study exempt from ethical review because existing data with patient de-identifiers were used. This study included patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database who met the following criteria: (1) age older than 17 years; (2) pathologically confirmed LCNC (International Classification of Disease for Oncology third edition code: 8013/3) between 2010─2015 [12]; (3) one primary only; (4) follow-up information was complete; (5) without distant metastasis of lymph node (N3) or/ and other organs (M1). In addition, patients who met the following standards were excluded from this study: (1) patients who had unknown surgery records; (2) patients who had an unknown tumor (T) or/ and node (N) classification. Details of the patient selection standards are shown in Fig. 1.

Follow-up

Cancer-specific survival (CSS) is the duration from the diagnosis to death caused by lung cancer, which was regarded as our observational endpoint. The eligible patients had a clear survival time and survival status.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 25.0 software (IBM SPSS, Inc, Armonk, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was used to determine the associations between surgery and other clinical features. Univariable and multivariable proportional hazard regression models were used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) on cancer-specific mortality. Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank tests were performed to draw and compare survival curves between the groups. Statistical tests were considered statistically significant with a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Propensity-score matching

To minimize the bias effect of other clinical variables, we used sex, age, marital status, tumor location, laterality, N stage, T stage, grade, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy as matching variables [6, 13]. After propensity-score matching (PSM) with a match tolerance of 0.01, the equilibrium test between the groups was checked via the χ2 test. The ratio of PSM was 1:1.

Results

Patient characteristics

In the present study, 453 patients were eligible for main analyses. The man patients outnumbered woman patients (52.5% vs. 47.5%). Most patients were over 65 years (n = 233, 51.4%). Two hundred ninety-nine patients received surgery, and the majority of patients who underwent surgery were in the T1 or N0 stage. Overall, significant differences in all clinicopathological variables except sex and age (Table 1, all P < 0.05) before PSM. To better compare the two groups, using PSM at a ratio of 1:1, 154 patients remained in the group. Except for marital status (P < 0.001), there were no significant differences in the clinicopathological patient characteristics between the two groups after PSM, as shown in Table 1.

Survival outcomes

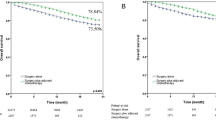

The median survival time of this cohort was 24.0 months (range 0─106.0 months). The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year CSS rates were 60.0%, 45.0%, and 42.0% in those 453 LCNC patients, respectively. Besides, the cases with surgery had better survival than cases without surgery (Fig. 2A, Log-rank P < 0.001). Compared with patients who underwent surgical resection, patients without surgery had a lower 5-year CSS rate (18.0% vs. 52.0%). Moreover, in the matched cohort, surgery’s role in the prognosis was encouraging. The surgery improved the 5-year CSS rate for this group of patients by 27% (Fig. 2B, Log-rank P < 0.001). After analyses of univariable and multivariable Cox regression, chemotherapy, T stage, N stage, and surgery (adjusted HR 0.315, 95%CI 0.218─0.457, P < 0.001) were identified as independent prognostic indicators (Table 2, all P < 0.05).

A sub-group analysis was performed further to explore surgery’s prognostic significance in old LCNC patients. In the cohort of old patients, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year CSS rates were 58.0%, 41.0%, and 37.0%, respectively. In addition, the median survival time was longer in cases after surgery than those without surgery (13.0 months vs. NA, Fig. 3A, P < 0.001). Besides, we explored the prognostic characteristics of old LCNC patients. Surgery, T stage, N stage, and chemotherapy were confirmed as independent prognostic factors (Table 3, all P < 0.05).

Then, we further investigated the role of surgery on patients with different clinical characteristics. In the other groups, the receiving surgery was a protective prognostic factor (Table 4, all HR < 1, all P < 0.05). In addition, for the cohort with stage T1-2N0-2M0, patients after the operation had more improved outcomes than patients without surgery (Fig. 3B, P < 0.001).

Discussion

The discussion on pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma has focused mainly on small-cell carcinoma. For LCNC, studies on surgery affecting survival still need to be completed. Thus, in the present study, we used a database of a large sample size to explore the association between surgery and prognosis in LCNC patients. The univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were used to identify the factor affecting prognosis. In addition, we used PSM analysis to confirm that receiving surgery could improve the survival outcomes of LCNC patients and reduce bias from other clinical and pathological features. Sub-group analyses were performed further to explore the relationship between surgery and other characteristics. Besides, we found that patients with operation had better survival than patients without surgery in cohorts with different clinical and pathological factors, such as old age, stage T1-4N0-2M0, and chemotherapy. Therefore, we propose that LCNC patients should undergo surgery if there are no contraindications to surgery.

As a classical treatment approach, surgical resection has been proven to be associated with extended survival in patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma [6, 14, 15]. Previous studies focused on small-cell lung cancer and reported that patients with stage I-IIA were more appropriate to receive surgery than those with stage IIb-III [5, 16]. Recently, a study from Gao et al. suggested that patients with stage III who underwent surgery had potential survival benefits [17]. Accordingly, those results indicated that the staging status of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma suitable for the surgery needed to be further determined. In the present study, we investigated the prognostic significance of surgery in LCNC patients with stage T1-2N0-2M0 and found that those patients with operation had improved survival outcomes. Besides, surgery could provide an improved prognosis in different statuses of the N stage, including N0, N1, and N2. Therefore, we suggest that the surgery is a worthy treatment approach for LCNC patients with clinical stage T1-4N0-2M0 to consider.

In addition, old age was not a prognostic risk factor statistically in this study, unlike other studies [18, 19]. The reason for this phenomenon might be that the sample size was small, and the cutoff point of age was different. For elderly lung cancer patients, it has been controversial whether surgery is performed or not [20,21,22]. In this study, we performed a sub-group analysis in patients with ages > 65 years and found that old patients could reach a longer median survival time after surgery. Therefore, a study by Rogers SO Jr et al. revealed that age was not a limiting factor for surgery [20]. Whether the surgery is performed or not depends mainly on the patient’s concomitant disease, lung function, and other contraindications to surgery. With the popularity of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, patients’ postoperative recovery period has been shortened, and patients suffer less pain and postoperative complications [23]. In addition, a recent report uncovered that overall survival and recurrence-free survival in patients with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was comparable to cases using traditional thoracotomy [23]. Those findings provided for the surgical treatment of elderly LCNC patients.

Some inevitable limitations should be indicated in this study. First, the clinical and pathological characteristics analyzed in this study are not comprehensive because the quantity of data released in SEER is limited; thus, the potential bias or error could be caused although the PSM was performed. Second, tumor markers and molecular tests were not included in our study. Third, the study was retrospective though it had a large sample size. Thus, we still need prospective studies to confirm those findings.

Conclusions

We proposed that the surgery could improve the survival outcomes of LCNC patients with stage T1-4N0-2M0. Moreover, old patients could benefit from surgery.

Data Availability

Any researchers interested in this study could contact us to request the data.

Abbreviations

- LCNC:

-

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- CSS:

-

Cancer-specific survival

- T:

-

Tumor

- N:

-

Node

- M:

-

Metastasis

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- PSM:

-

Propensity-score matching

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33.

Wu LL, Li CW, Lin WK, Qiu LH, Xie D. Incidence and survival analyses for occult lung cancer between 2004 and 2015: a population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1009.

Zheng R, Zhang S, Wang S, Chen R, Sun K, Zeng H, Li L, Wei W, He J. Lung cancer incidence and mortality in China: updated statistics and an overview of temporal trends from 2000 to 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2(3):139–47.

Haruki T, Matsui S, Oshima Y, Maeta H, Fukino S, Yurugi Y, Araki K, Umekita Y, Nakamura H. Prognostic impact of surgical treatment for high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Thorac Dis. 2022;14(4):1070–8.

Wakeam E, Acuna SA, Leighl NB, Giuliani ME, Finlayson SRG, Varghese TK, Darling GE. Surgery Versus Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy for Early and locally Advanced Small Cell Lung Cancer: a propensity-matched analysis of Survival. Lung Cancer. 2017;109:78–88.

Chen X, Zhu JL, Wang H, Yu W, Xu T. Surgery and surgery Approach affect survival of patients with Stage I-IIA Small-Cell Lung Cancer: a study based SEER database by Propensity score matching analysis. Front Surg. 2022;9:735102.

Jiang WM, Wu LL, Wei HY, Ma QL, Zhang Q. A parsimonious Prognostic Model and Heat Map for Predicting Survival following adjuvant Radiotherapy in Parotid Gland Carcinoma with Lymph Node Metastasis. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021;20:15330338211035257.

Liu X, Wu L, Zhang D, Lin P, Long H, Zhang L, Ma G. Prognostic impact of lymph node metastasis along the left gastric artery in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16(1):124.

Wu L-L, Li C-W, Li K, Qiu L-H, Xu S-Q, Lin W-K, Ma G-W, Li Z-X, Xie D. The difference and significance of Parietal Pleura Invasion and Rib Invasion in pathological T classification with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front Oncol 2022, 12.

Lee SH, Seo HY, Kim HR, Song EK, Seon JK. Older age increases the risk of revision and perioperative complications after high tibial osteotomy for unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):24340.

Liu P, Wang Z, Zhang S, Ding G, Tan K, Zhou J. Application of endoprosthetic replacement in old patients with isolated proximal femoral bone metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2022.

Taioli E, Flores R. Appropriateness of Surgical Approach in Black Patients with Lung Cancer-15 years later, little has changed. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(3):573–7.

Huang W, Wu L, Liu X, Long H, Rong T, Ma G. Preoperative serum C-reactive protein levels and postoperative survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14(1):167.

Petrella F, Bardoni C, Casiraghi M, Spaggiari L. The role of surgery in High-Grade Neuroendocrine Cancer: indications for clinical practice. Front Med. 2022;9:869320.

Girelli L, Casiraghi M, Sandri A, Petrella F, Galetta D, Gasparri R, Maisonneuve P, Fazio N, Spaggiari L. Results of Surgical Resection of locally Advanced Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112(2):405–14.

Casiraghi M, Sedda G, Del Signore E, Piperno G, Maisonneuve P, Petrella F, de Marinis F, Spaggiari L. Surgery for small cell lung cancer: when and how. Lung Cancer. 2021;152:71–7.

Gao L, Shen L, Wang K, Lu S. Propensity score matched analysis for the role of surgery in stage small cell lung cancer based on the eighth edition of the TNM classification: a population study of the US SEER database and a chinese hospital. Lung Cancer. 2021;162:54–60.

Liu B, Qian JY, Wu LL, Zeng JQ, Xu SQ, Yuan JH, Zheng YL, Xie D, Chen X, Yu HH. A long waiting time from diagnosis to treatment decreases the survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients with stage IA1: a retrospective study. Front Surg. 2022;9:987075.

Wu LL, Qian JY, Li CW, Zhang Y, Lin WK, Li K, Li ZX, Xie D. The Clinical and Prognostic Characteristics of Primary Salivary Gland-Type Carcinoma in the Lung: A Population-Based Study. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14(19).

Rogers SO Jr, Gray SW, Landrum MB, Klabunde CN, Kahn KL, Fletcher RH, Clauser S, Tisnado D, Doucette W, Keating NL. Variations in surgeon treatment recommendations for lobectomy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer by patient age and comorbidity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1581–8.

Ye X, Liu Y, Yang J, Wang Y, Cui X, Xie H, Song L, Ding Z, Zhai R, Han Y, et al. Do older patients with stage IB non-small-cell lung cancer obtain survival benefits from surgery? A propensity score matching study using SEER data. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48(9):1954–63.

Sandler BJ, Wang Z, Hancock JG, Boffa DJ, Detterbeck FC, Kim AW. Gender, Age, and Comorbidity Status Predict Improved Survival with Adjuvant Chemotherapy following lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancers larger than 4 cm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(2):638–45.

Soldath P, Binderup T, Carstensen F, Clausen MM, Kjaer A, Federspiel B, Knigge U, Langer SW, Petersen RH. Long-term outcomes after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in pulmonary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Surg Oncol. 2022;41:101728.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the staff from the SEER database. In addition, we are personally very grateful to Dr. Lei-Lei Wu for his summary of the SEER database, which helped us a lot.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872433) and the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2023RC270).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJ and XC contributed to the study design, data collection, data analyses, data interpretation, and manuscript drafting. WX contributed to data analyses and manuscript review. XL, HW, and WJ Y contributed to data interpretation and manuscript reviews. All authors contributed to the final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of The Affiliated People’s Hospital of Ningbo University approved this study and considered this study exempt from ethical review because existing data with patient de-identifiers were used.

Consent for publication

Not available.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, H., Xie, W., Li, X. et al. The survival benefit from surgery on patients with large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma in the lung: a propensity-score matching study. J Cardiothorac Surg 18, 216 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-023-02314-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-023-02314-1