Abstract

Background

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a well-established therapeutic option for the management of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. The simultaneous migration of the coil and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) is an extremely rare but significant complication after TIPS. Because of its rare presentation, there are currently no definitive recommendations for the management of this condition.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old man with hepatitis B cirrhosis underwent TIPS placement for uncontrolled gastroesophageal varix (GEV) bleeding secondary to portal hypertension in August 2018. During the procedure, large GEVs were embolized using a coil and NBCA. After a year, coil and NBCA migration into the stomach was observed. Attempts to remove the coil using biopsy forceps during esophagogastroduodenoscopy failed. The patient refused further intervention on the coil to prevent further complications and received conservative therapy instead. Close surveillance with endoscopy is recommended for detecting coils and varices.

Conclusions

The present case reports an extremely rare but significant complication after TIPS, which highlights the management and follow-up recommendation for such rare complications. Our experience may provide guidance for the management of future similar cases and stimulate discussion about treatment methods of similar patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hemorrhage from gastroesophageal varices (GEVs) is a life-threatening sequela of portal hypertension and a major cause of mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis [1, 2]. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), as a second line treatment in GEVs bleeding after failure of endoscopic treatment or in case of preemptive TIPS can be performed together with endoscopic band ligation, is a well-established therapeutic option for the management of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis [3, 4]. Adjunct embolization of GEVs using coil and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) could be useful at the time of TIPS insertion to reduce bleeding of GEVs [5]. The simultaneous coil and NBCA migration into the stomach after TIPS is extremely rare. Because of the lack of clinical reports on this condition exist, there are currently no recommended definitive treatments for such cases. Herein, we report one case admitted to our department in August 2018 with a subsequent review of the literature.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with repeated melena for the past month. The clinical abdominal examination on admission revealed a soft abdomen. The Murphy sign and shifting dullness were negative. Percussive examination in spleen area showed that the lower margin of the dullness boundary was located 3 cm below the costal margin. The patient had had hepatitis B cirrhosis for more than 10 years and took oral entecavir (0.5 mg, Squibb, Shanghai, China) daily as antiviral therapy. One month ago, the patient was treated by endoscopy at the local hospital due to melena caused by GEVs bleeding, but the effect was limited because of severe and extensive GEVs, and the patient had repeated melena again. After admission, routine blood examination revealed leukopenia 1.7 × 109/L, mild low hemoglobin 112 g/L and thrombocytopenia 30 × 109/L. The blood biochemistry tests showed a slightly elevated total bilirubin of 25.1 μmol/L (normal range < 21 μmol/L). The prothrombin time was slightly increased at 14.9 s. HBsAg and HBcAb results were positive. Hepatitis B virus DNA was increased at 1.81 × 102 IU/mL. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen indicated hepatic cirrhosis, portal hypertension (the main portal vein was dilated with a diameter of 18 mm), splenomegaly and gastroesophageal varices. The final diagnosis of the presented case were GEVs bleeding secondary to portal hypertension, hepatic cirrhosis and splenomegaly.

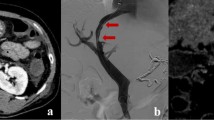

The patient underwent TIPS placement for uncontrolled bleeding following a multidisciplinary expert consultation in August 2018. The portal venogram displayed a large drainage into the GEVs from the splenic vein (Fig. 1a). After identification of the GEVs, a soft detachable coil (Boston Scientific, Natick, USA) and NBCA (Histoacryl, Braun, Germany) were deployed for safe and complete embolization during TIPS (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, an intrahepatic shunt tract was created with an 8-mm-diameter covered stent (Gore, Newark, USA) and an 8-mm-diameter bare stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, USA) between the right hepatic and portal veins. The TIPS was performed successfully. The pre-TIPS portosystemic pressure gradient (PSG) was 20 mmHg, and the final PSG was 8 mmHg. The postinterventional venogram showed complete occlusion of the GEVs (Fig. 1c). The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no immediate complications occurred. Hemostasis was also achieved.

Large GEVs were embolized during the TIPS procedure. a Portal venogram demonstrating the GEVs supplied via the splenic vein (white arrow). b The GEVs were managed with a proximal detachable coil (white arrow) and distal NBCA (black arrow) embolization. c Portal venogram performed after TIPS creation showed complete occlusion of the GEVs (black arrow). GEVs, gastroesophageal varices; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; NBCA, n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate

One year after TIPS creation, a follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan showed that a portion of the variceal coil had migrated into the gastric lumen through the site of the previously embolized gastric varix (Fig. 2a), and the NBCA was not seen in the position of the former GEVs on the scout images (Fig. 2b). Subsequent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed coil erosion through the stomach wall with no active bleeding (Fig. 2c). However, the patient remained asymptomatic. In March 2021, the patient was again admitted to our hospital because of melena. An EGD was performed, which showed the endovascular coil extending through the gastric wall with multiple incarcerated ulcers (Fig. 2d). During the EGD, attempts to remove the coil using biopsy forceps failed. The patient refused intervention on the coil to prevent further complications since his melena symptoms improved after conservative treatment. Our plan is to repeat EGD after 3–6 months for surveillance of the coil and varices.

CT and EGD follow-up after TIPS. a Abdominal axial CT demonstrated the coil from the GEVs protruding into the stomach (white arrow). b Digital scout image revealing migration of the coil (black arrow). The coil was straightened, and NBCA was not visualized. c EGD view of the coil and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate migrating into the gastric wall. Adhesion of the remnants of NBCA at the surface of the coil (black arrow). d The coil extended through the gastric wall, resulting in multiple incarcerated ulcers (white arrow). CT, computed tomography; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GEVs, gastroesophageal varices; NBCA, n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Discussion and conclusions

NBCA is a liquid adhesive agent that can rapidly induce the process of polymerization and solidify when it comes in contact with solutions (such as blood) that contain anions, thereby promoting vessel obliteration, inflammation, and fibrosis [6]. Because of the high risk of pulmonary embolism, coils were used to slow down the blood flow during the embolization of varicose veins [7]. The migration of both the coil and NBCA is an extremely rare complication after TIPS, with only one case having been reported (Table 1). Kupkova et al. [8] incidentally found a metallic coil and NBCA that penetrated into the stomach three weeks after TIPS. Eleven months after TIPS, the coil spontaneously dropped from the gastric varices into the stomach without bleeding symptoms. In our case, the late-onset migration of the coil and NBCA occurred a year after TIPS, and the primary reason for migration in our patient may have differed from that of Kupkova et al. In our patient, the migration was most likely related to the recurrence of portal hypertension caused by the progression of portal thrombosis [9, 10]. The variceal lumen might have widened due to recurrent portal hypertension, leading to migration of the coil and NBCA. Secondly, it is possible that the migration of coils and NBCA can be favorite by the size of coils and amount of NBCA. In addition, the immune response is a potential promigratory factor, as it functions to eliminate and isolate foreign material. Adhesion of macrophages at the surface of the foreign body and formation of a fibrous capsule with the release of degradation mediators are important components of the immunologic response [11]. Local inflammation and fistula formation may have also played a role [12].

Separate coil migration and penetration following TIPS placement are also rarely documented, with only seven cases having been reported in the English literature (Table 2) [9, 10, 12,13,14,15,16]. Because of the rarity of such complications in the literature, it is difficult to make recommendations for the management of this condition. However, considering the different clinical evolutions of such cases, each patient requires an individual assessment. Three case reports have described coil migration without active bleeding following TIPS creation. No further intervention was performed for the migrated coils [12,13,14]. Merchant et al. [9] reported a case of coil erosion through a gastric varix into the gastric lumen without active hemorrhage after liver transplantation. The migrated coil was left in situ. Unfortunately, the patient died of progressive dyspnea and subsequently developed polymicrobial sepsis. Similarly, another case reported coil penetration into the stomach after liver transplantation. Urgent laparotomy and partial gastrectomy were performed because of massive hematemesis. Unfortunately, the patient died two days after the surgery [15]. Lucas et al. [10] described a case of gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to coil extrusion after TIPS creation in a patient treated with sorafenib. The portal stent was repermeabilized, and the gastric varices were embolized using a plug. Another report described embolization coil erosion through the duodenal varix following TIPS creation. The penetrating coil was removed using endoscopic forceps [16]. In our case, the patient refused further intervention to retrieve the coil and instead received conservative therapy. Appropriate treatment should be given once signs of bleeding are noted to ensure a good prognosis for the patient. Therefore, close surveillance with endoscopy is recommended for detecting the coil and varices.

There are currently no recommended definitive treatments for such cases. However, from our experience, we may be able to provide information for future cases, as this complication should be based on individual patient assessments, such as in our case. Although the outcome of this complication is unknown to date, it may potentially contribute to rebleeding or gastric perforation [14]. Furthermore, there is a likelihood of spontaneous dropout of the coil, similar to that of Kupkova et al. Because the migration of the coil and NBCA in our patient was likely related to recurrent portal hypertension, long-term follow-up is mandatory not only to detect such late complications as soon as possible but also to evaluate the progression of cirrhosis, stent patency, and portal thrombosis. Nonetheless, when such complications occur, it is essential to consider the case thoroughly, react appropriately, and learn from the experience [17].

The current case presents an extremely rare but significant complication after TIPS. Our report highlights the management and follow-up recommendation for such rare cases. Since this is only the second case of simultaneous migration of a coil and NBCA, our experience may provide guidance for the management of future similar cases and stimulate discussion about treatment methods of similar patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EGD:

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- GEVs:

-

Gastroesophageal varices

- NBCA:

-

N-Butyl-2-cyanoacrylate

- PSG:

-

Portosystemic pressure gradient

- TIPS:

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

References

Seo YS. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:20–42.

Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Practice guidelines committee of the American association for the study of liver diseases; practice parameters committee of the American college of gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–38.

Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Travis S, Armstrong MJ, Tsochatzis EA, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut. 2020;69:1173–92.

Alqadi MM, Chadha S, Patel SS, Chen YF, Gaba RC. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation for treatment of gastric varices: systematic literature review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2021;44:1231–9.

Trebicka J. Emergency TIPS in a Child-Pugh B patient: When does the window of opportunity open and close? J Hepatol. 2017;66:442–50.

Kamani L, Ahmad BS, Arshad M, Ashraf P. Safety of endoscopic N-Butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate injection for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices in children. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34:1363–8.

Irisawa A, Obara K, Sato Y, Saito A, Orikasa H, Ohira H, et al. Adherence of cyanoacrylate which leaked from gastric varices to the left renal vein during endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: a histopathologic study. Endoscopy. 2000;32:804–6.

Kupkova B, Fejfar T, Krajina A, Hulek P, Tacheci I, Bures J. Porto-gastric fistula due to penetration of metallic coil into the stomach: a rare complication of endovascular treatment of gastric varices. A Case report. Folia Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3):107–11.

Merchant M, Mahendra D, Martin J, Chen R, Resnick S. Portogastric fistula complicating remote gastric variceal coil embolization. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2013;6(5):395–7.

Lucas E, Aubourg A, Bacq Y, Perarnau JM. Coil extrusion from a gastric varice during sorafenib treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(11):920.

Klopfleisch R, Jung F. The pathology of the foreign body reaction against biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2017;105(3):927–40.

Hussain S, Ghaoui R. Porto-gastric fistula from penetration of coil from gastric varix after TIPS procedure for bleeding gastric varices. J Interv Gastroenterol. 2011;1(1):33.

Oza VM, Levine E, Kirkpatrick R. Rare complication of variceal embolization: a novel case. J Interv Gastroenterol. 2013;3(3):113–4.

Pusateri AJ, Makary MS, Mumtaz K. Migration of gastric varix coil after balloon-occluded antegrade transvenous obliteration. ACG Case Rep J. 2020;7(10):e00472.

Levi Sandri GB, Lai Q, Mennini G, Trentino P, Berloco PB, Rossi M. Massive bleeding from a gastric varix coil migration in a liver transplant patient. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2013;22(3):249.

Soape MP, Lichliter A, Cura M, Lepe-Suastegui MR, Burdick JS. Rare duodenal varix coil erosion post TIPS creation and coil embolization of mesenteric-systemic shunt. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(9):2601–3.

Gaba RC, Khiatani VL, Knuttinen MG, Omene BO, Carrillo TC, Bui JT, et al. Comprehensive review of TIPS technical complications and how to avoid them. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(3):675–85.

Acknowledgements

The patient signed a written informed consent form for the purpose of publication of the results of this case study.

Funding

The present work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81971713), Health Commission of Zhejiang Province (Grant No.JBZX-202004), Research Unit of Collaborative Diagnosis and Treatment for Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Grant No.2019RU019). The funding body had no role in designing research and collecting, analyzing and interpreting data and writing manuscripts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y-LZ and J-HS: conception and design. Y-LZ, C-HN, H-TC and QX: data collection. T-YZ, S-QC and G-HZ: data analysis and interpretation. Y-LZ, H-LW, B-QW and Z-NY: drafting the article. Y-LZ, T-YZ, LJ and J-HS: critical revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, YL., Nie, CH., Zhou, TY. et al. Coil and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate migration into the stomach after TIPS for gastroesophageal variceal bleeding: a case report and literature review. J Cardiothorac Surg 17, 304 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-022-02062-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-022-02062-8