Abstract

Background

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is considered to be one of the most challenging complications of joint replacement, which remains unpredictable. As a simple and emerging biomarker, calprotectin (CLP) has been considered to be useful in ruling out PJI in recent years. The purpose of this study was to investigate the accuracy and sensitivity of CLP in the diagnosis of PJI.

Methods

We searched and screened the publications from PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library from database establishment to June 2021. Subsequently, Stata version 16.0 software was used to combine the pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), operating characteristic curve, and area under the curve (AUC). Heterogeneity across articles was evaluated by the I2 statistics. Finally, sources of heterogeneity were detected by subgroup analysis based on study design, detection method, sample size, and cutoff values.

Results

A total of 7 studies were included in our study, comprising 525 patients. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR, and NLR of CLP for PJI diagnosis were 0.94(95% CI 0.87–0.98), 0.93(95% CI 0.87–0.96), 13.65(95% CI 6.89–27.08), and 0.06(95% CI 0.02–0.15), respectively, while the DOR and AUC were 222.33(95% CI 52.52–941.11) and 0.98 (95% CI 0.96–0.99), respectively.

Conclusion

Synovial CLP is a reliable biomarker and can be used as a diagnostic criterion for PJI in the future. However, the uncertainty resulting from the poor study numbers and sample sizes limit our ability to definitely draw conclusions on the basis of our study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is one of the most serious complications after arthroplasty. Infections accounted for 25% of revisions, and its prevalence is expected to increase notably over the next decades [1]. PJI will not only aggravate the financial burden of patients, but also affect quality of life and interfere with joint function [2, 3]. Since the symptoms of PJI are usually non-specific, it is difficult to diagnose PJI accurately and quickly, which delays the optimal treatment time for PJI and prevents patients from achieving a satisfactory prognosis [4]. Consequently, various diagnostic guidelines and criteria have been proposed, including the International Consensus Meeting (ICM) diagnostic criteria, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeon (AAOS)’s guidelines, and Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) [5,6,7]. Although there are currently a series of diagnostic guidelines, PJI may be present without meeting these algorithms clinically, specifically in patients with less virulent organisms and negative culture [8].

Therefore, there is a clinical need for a reliable and easily available diagnostic biomarker to achieve rapid diagnosis and differentiation in various situations. Calprotectin (CLP) is derived from neutrophils and macrophages. As an inflammatory reactant, its release and expression levels will increase in infection, trauma, and inflammatory diseases [9,10,11]. Follow-up studies focusing on the diagnostic accuracy of novel biomarkers have proved that CLP is a useful biomarker, which has the characteristics of rapid evaluation, high sensitivity, and specificity [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Nevertheless, because of the small sample size and inconsistent results, their conclusions have not been recognized. Therefore, given the ambiguities and uncertainties in the evidence [14], we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of these literatures to study the diagnostic value of CLP in PJI.

Method

This article is conducted as claimed by recommendations of the Cochrane and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. Ethical approval was not necessary for this article and the research protocol had not been registered, because this research only involves the review of published articles. The research protocol is decided by all authors.

Search strategy

Two researchers systematically conducted electronic searches to identify all eligible articles in the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science database, while the searches were performed from the inception of each database through to June 2021. Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and entry terms contained in the search strategy were as follows: “Prosthesis-Related Infections” OR “Prosthesis Related Infections” OR “Infections, Prosthesis-Related” OR “Prosthesis-Related Infection” OR “Peri-Prosthetic Joint Infection” OR “Periprosthetic Joint Infection” OR “Prosthetic joint infection” OR “PJI” represented disease, “Calprotectin” OR “Calgranulin” OR “Leukocyte L1 Antigen Complex” stranded for target index.

Selection of study

Literature was included if it met the following inclusion criteria: (1) using CLP as an index for the diagnosis of PJI, (2) the integrated data (true positive, false negative, false positive, true negative) were provided directly or indirectly, (3) A definite gold standard is used in the research, such as MSIS or ICM. The exclusion criteria mainly include: (1) animal studies; (2) studies with incomplete data; (3) reviews, comments, and letters.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Relevant information was independently recorded by two reviewers from all selected studies, and the extracted data are input into a sheet in Excel. Variables extracted were: (1) first author, the year in which the article was published, the country, the design type of the study, location of arthroplasty; (2) gender, average age of patients, the gold standard, the detection method, and the cutoff value of CLP; (3) sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR), negative LR, diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), area under the curve (AUC). Then, two researchers used The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) [20] in the Revman (version5.4) software to evaluate the quality of all the literature, which is composed of patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. If there is any disagreement in this process, the third author is responsible for making the decision.

Statistical analysis

All extracted data analysis and picture production are performed with the Stata16.0 software. Bivariate random effect model was selected to analyze the tp, fp, fn, and tn values of 2 × 2 table recorded in the sheet and to test the heterogeneity. The sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), diagnostic score, and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were calculated after integration. In addition, by drawing the summary receiver operating characteristics (SROC) through the Midas command, the calculated area under the curve (AUC) discriminates the diagnostic ability of CLP.

After that, the I2 statistics were performed to assess the heterogeneity of the studies. Statistically, the bigger the I2, the bigger the heterogeneity. If the heterogeneity of the article is too large, we will identify the source of the heterogeneity through subgroup analysis. Preplanned subgroups were designed according to the type of cutoff values used in the study, study design, sample size, detection method, and sample size.

The Deeks’ funnel plot was applied to evaluate the publication bias, while the Fagan plot was used to clearly reflect the change of the diagnostic value of CLP on the incidence of PJI.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

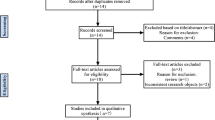

The flowchart of the literature screening process is summarized in Fig. 1. An electronic search yielded 12 studies in PubMed (MEDLINE), 15 in EMBASE, 14 in Web of Science, and one in the Cochrane Library. No other publications were found by manual search. After the removal of 22 duplicates, 20 studies remained; Then 9 articles were excluded based on titles and abstracts, including 6 inconsistent contents, 2 letters, and 1 comment. Among the remaining 20 articles, 4 were deleted after reading the full article, including 2 literatures with insufficient data, and 2 reviews. This process ultimately resulted in 7 studies that were eligible for the final meta-analysis.

A total of 525 patients were enrolled in seven studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18], including 320 patients with non-PJI and 205 patients with confirmed PJI. Most of these patients underwent knee or hip replacement, and some have undergone total joint replacements such as shoulder and elbow joints. Six of the studies were prospective and one was retrospective. In addition, the sample types used in the included articles were all synovial fluid, and one of them also measured calprotectin in blood. All studies provided methods for the detection of calprotectin. Three papers use ELISA and lateral flow assay, respectively, and one paper used both detection methods for comparison. Four studies regarded MSIS as the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of PJI, and three studies adopted ICM as “the gold standard” for diagnosis. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of all eligible studies. A summary of data extraction results (2 × 2 table) is offered in Table 2.

Quality assessment and publication biases

The quality assessment results of 7 studies using the QUADAS-2 scale are indicated in Fig. 2. The figure shows that the overall quality of the included studies was good, with only two studies are “high risks,” and the rest are “unclear” or “low risk.” Although the sample size of the included literature is relatively small, the quality of the research is persuasive. In addition, the funnel plot asymmetry demonstrated no obvious publication bias was detected (P = 0.18) (Fig. 3).

Diagnostic accuracy of calprotectin for PJI

Forest plots in Fig. 4 revealed that the pooled sensitivity across studies for CLP was 0.94(95% CI 0.87–0.98), the pooled specificity was 0.93(95% CI 0.87–0.96), the pooled positive LR was 13.65(95% CI 6.89–27.08), the pooled negative LR was 0.06(95% CI 0.02–0.15), and the pooled DOR was 222.33(95% CI 52.52–941.11) (Fig. 5). The I2 statistics for sensitivity and specificity were 71.1% (95% CI 48.6–93.6) and 76.9% (95% CI 59.9–94.0), showing that there was significant heterogeneity. The SROC curve indicated the sensitivity and specificity, as well as the prediction regions, with an AUC of 0.98 (95% CI 0.96–0.99) (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 7, the Fagan plot demonstrated that a positive result on the CLP test increased the probability of PJI from 14 to 77% and a negative result on the CLP test decreased the probability of PJI to 2%.

Subgroup analysis

For all 7 studies, the heterogeneity (I2) was shown for sensitivity and specificity among studies of both index tests. Thus, we performed a subgroup analysis of factors that may be the possible sources of heterogeneity, including study design, detection method, sample size, and cutoff values (Table 3). When only analyzing 6 prospective studies, the sensitivity and specificity of CLP increased to 0.96 (95% CI 0.91–0.98) and 0.95(95% CI 0.91–0.97), respectively, while I2 statistics decreased significantly (24.21% vs. 71.11%, 0.00% vs. 76.9%), suggesting that study design is the source of heterogeneity. In addition, PJI was more diagnostically accurate in studies using ELISA as the detection method compared with studies using lateral flow assay.

Discussion

Although the incidence of PJI is about 1–2%, the economic burden it brings is heavy, early diagnosis of PJI is the key to the effective reduction of patient burden and successful management [21]. Therefore, the ability to distinguish between septic and aseptic failure of the prosthesis is crucial, because the treatment of PJI patients to eradicate infected microorganisms is much more complicated [22]. The diagnosis of PJI depends on the combination of serologic testing, synovial fluid aspiration, radiographic evaluation, microbiology, and histopathological examination in addition to clinical symptoms [23, 24].

Currently, the only serum biomarkers recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) for the diagnostic evaluation of PJI are serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), which are not specific [5]. Hence, researchers have become increasingly aware of the significance of investigating and developing the emerging diagnostic biomarkers for PJI. It is gratifying that more and more biomarkers for the diagnosis of PJI have been discovered, including α-defensin, leukocyte esterase [LE], interleukin [IL]-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1b, Procalcitonin and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha, and so on [25, 26].

Recently, several investigators considered CLP as a promising biomarker. During inflammation, CLP is actively released and exerts a key role by stimulating leukocyte recruitment and inducing cytokine secretion, so it can be used as a biomarker for diagnosis and follow-up and a predictor of response to inflammation-related diseases [10, 11]. In the previous literature, CLP had been reported to predict or evaluate the progress of inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [27, 28], rheumatoid arthritis [29, 30], and spondyloarthritis [31]. However, it was not until 2017 that Bakker et al. [16] first reported the role of CLP in diagnosing PJI. Because of its good diagnostic accuracy, an increasing number of studies have attempted to investigate the function of CLP. To our knowledge, our study is the first meta-analysis evaluating the ability of CLP in the diagnosis of PJI after a literature review.

Our study revealed that CLP indicated a comparable, extremely high diagnostic value to identify PJI (with a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.94(95% CI 0.87–0.98) and 0.93(95% CI 0.87–0.96), respectively). The pooled positive LR was 13.65(95% CI 6.89–27.08) and the pooled negative LR was 0.06(95% CI 0.02–0.15), with an AUC of 0.98 (95% CI 0.96–0.99). This result is much better than commonly used biomarkers, which may provide a new alternative for the diagnosis of PJI. The effectiveness of clinical diagnostic indicators is usually evaluated by LR and DOR. In the guide, LR + > 5, LR − < 0.2 or DOR > 10 are considered to be good predictive values, and LR + > 2, LR − < 5 or DOR > 4 are considered to be possible predictive values [32, 33]. Therefore, CLP is a superior predictor for diagnosing PJI, no matter when LR or DOR is used as the reference parameter. Another parameter widely used in diagnostic tests is the posttest probability, which reflects the probability of a PJI patient when the test result is negative or positive. The Fagan diagram shows that the CLP's ability to distinguish PJI is excellent.

Apparently, there is a degree of heterogeneity in the studies we pooled. Therefore, we performed a reasonable subgroup analysis to find the source of heterogeneity. The results of the subgroup analyses suggested that the heterogeneity may be the result of differences in the type of study and the detection method, and the heterogeneity is greatly reduced after removing the retrospective study. The study of Trotter et al. [14] is the only retrospective study included in the literature, and its overall accuracy of to diagnose PJI was 75.36%, which is lower than the other 6 studies. The authors suggest that the use of frozen storage samples may lead to leukocyte lysis and increased calprotectin during freeze–thaw process, while relevant study was lacking recently.

According to the results of subgroup analysis, the significance across studies heterogeneity could be accounted by the different tests. The methods of CLP measurement in our included studies were lateral flow test (LFA)or ELISA, and the results of the subgroup analysis show that the diagnostic accuracy for PJI using lateral flow assay obtained a lower accuracy in our analysis. A recent study by Suen et al. [34] indicated similar performance differences between the Synovial αdefensin lateral flow test and the αdefensin ELISA method. However, LFA is now a reliable diagnostic tool in numerous fields where portable, simple, and particularly rapid on-site detection methods are needed [35].

There were some limitations in our research. First, this study only included 7 articles, so the sample size was relatively small, with only 205 cases in the PJI group and 320 cases in the non-PJI group. Second, there is currently no gold standard for testing PJI, and it is possible that some positive patients are still missed because the gold standard cannot be tested. Due to limited data, we were unable to conduct subgroup analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of synovial fluid and serum CLP. And so far, there is not enough literature to clarify whether the CLP method can improve the outcome of patients receiving antibiotics.

Conclusions

The present study indicated that CLP detection of PJI has good diagnostic accuracy and specificity. Hence, it can be considered a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of PJI. However, the present data remain insufficient and further studies regarding the combination of CLP and other biomarkers for diagnosing PJI are warranted.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to feasibility but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PJI:

-

Periprosthetic joint infection

- CLP:

-

Calprotectin

- AAOS:

-

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeon

- MSIS:

-

Musculoskeletal Infection Society

- ICM:

-

International Consensus Meeting

- LR:

-

Likelihood ratio

- DOR:

-

Diagnostic odds ratio

- SROC:

-

Summary receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

References

Kapadia BH, Berg RA, Daley JA, Fritz J, Bhave A, Mont MA. Periprosthetic joint infection. The Lancet. 2016;387(10016):386–94.

Kapadia BH, McElroy MJ, Issa K, Johnson AJ, Bozic KJ, Mont MA. The economic impact of periprosthetic infections following total knee arthroplasty at a specialized tertiary-care center. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):929–32.

Wildeman P, Rolfson O, Söderquist B, Wretenberg P, Lindgren V. What are the long-term outcomes of mortality, quality of life, and hip function after prosthetic joint infection of the hip? A 10-year follow-up from Sweden. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021.

Tande AJ, Gomez-Urena EO, Berbari EF, Osmon DR. Management of prosthetic joint infection. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2017;31(2):237–52.

Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson WR, Infectious Diseases Society of A. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013; 56(1):e1–25.

Parvizi J, Della Valle CJ. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline: diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(12):771–2.

Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Della Valle CJ, Garvin KL, Mont MA, Wongworawat MD, Zalavras CG. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(11):2992–4.

Li C, Renz N, Trampuz A, Ojeda-Thies C. Twenty common errors in the diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infection. Int Orthop. 2020;44(1):3–14.

Bresnick AR. S100 proteins as therapeutic targets. Biophys Rev. 2018;10(6):1617–29.

Sreejit G, Flynn MC, Patil M, Krishnamurthy P, Murphy AJ, Nagareddy PR. S100 family proteins in inflammation and beyond. Adv Clin Chem. 2020;98:173–231.

Wang S, Song R, Wang Z, Jing Z, Wang S, Ma J. S100A8/A9 in inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1298.

Grzelecki D, Walczak P, Szostek M, Grajek A, Rak S, Kowalczewski J. Blood and synovial fluid calprotectin as biomarkers to diagnose chronic hip and knee periprosthetic joint infections. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-b(1):46–55.

Salari P, Grassi M, Cinti B, Onori N, Gigante A. Synovial fluid Calprotectin for the preoperative diagnosis of chronic periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(2):534–7.

Trotter AJ, Dean R, Whitehouse CE, Mikalsen J, Hill C, Brunton-Sim R, Kay GL, Shakokani M, Durst AZE, Wain J, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a rapid lateral flow calprotectin test for the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint Res. 2020;9(5):202–10.

Warren J, Anis HK, Bowers K, Pannu T, Villa J, Klika AK, Colon-Franco J, Piuzzi NS, Higuera CA. Diagnostic utility of a novel point-of-care test of Calprotectin for periprosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103(11):1009–15.

Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, Ploegmakers JJW, Kampinga GA, Wagenmakers-Huizenga L, Jutte PC, Muller Kobold AC. Synovial calprotectin: a potential biomarker to exclude a prosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-b(5):660–5.

Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, Ploegmakers JJW, Ottink K, Kampinga GA, Wagenmakers-Huizenga L, Jutte PC, Kobold ACM. Synovial calprotectin: an inexpensive biomarker to exclude a chronic prosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):1149–53.

Zhang Z, Cai Y, Bai G, Zhang C, Li W, Yang B, Zhang W. The value of calprotectin in synovial fluid for the diagnosis of chronic prosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint Res. 2020;9(8):450–7.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):61-65 e61.

Zimmerli W, Moser C. Pathogenesis and treatment concepts of orthopaedic biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65(2):158–68.

Parvizi J, Gehrke T. Definition of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1331.

Workgroup Convened by the Musculoskeletal Infection S. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1136–8.

Lee YS, Koo KH, Kim HJ, Tian S, Kim TY, Maltenfort MG, Chen AF. Synovial fluid biomarkers for the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(24):2077–84.

Vicenti G, Bizzoca D, Nappi V, Pesce V, Solarino G, Carrozzo M, Moretti F, Dicuonzo F, Moretti B. Serum biomarkers in the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: consolidated evidence and recent developments. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(2 Suppl):43–50.

Bromke MA, Neubauer K, Kempinski R, Krzystek-Korpacka M. Faecal Calprotectin in assessment of mucosal healing in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(10):2203.

Fauny M, D’Amico F, Bonovas S, Netter P, Danese S, Loeuille D, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Faecal Calprotectin for the diagnosis of bowel inflammation in patients with rheumatological diseases: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(5):688–93.

Jarlborg M, Courvoisier DS, Lamacchia C, Martinez Prat L, Mahler M, Bentow C, Finckh A, Gabay C, Nissen MJ. Serum calprotectin: a promising biomarker in rheumatoid arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):105.

Ometto F, Friso L, Astorri D, Botsios C, Raffeiner B, Punzi L, Doria A. Calprotectin in rheumatic diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017;242(8):859–73.

Ma Y, Fan D, Xu S, Deng J, Gao X, Guan S, Pan F. Calprotectin in spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106948.

Glas AS, Lijmer JG, Prins MH, Bonsel GJ, Bossuyt PM. The diagnostic odds ratio: a single indicator of test performance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(11):1129–35.

Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users' guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The evidence-based medicine working group. Jama. 1994;271(9):703–7.

Suen K, Keeka M, Ailabouni R, Tran P. Synovasure “quick test” is not as accurate as the laboratory-based α-defensin immunoassay: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-b(1):66–72.

Chen YH, Gupta NK, Huang HJ, Lam CH, Huang CL, Tan KT. Affinity-switchable lateral flow assay. Anal Chem. 2021;93(13):5556–61.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JX, LZ, and KJ contributed to conceptualization. JL, ZY, and YL contributed to literature search. YL and LZ contributed to data extraction and quality assessment. XL, LH, and TX contributed to software. JL, JX, and CW contributed to formal analysis. JL and KJ contributed to validation. JX and JL contributed to writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Detailed search strategy of Pubmed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xing, J., Li, J., Yan, Z. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of calprotectin in periprosthetic joint infection: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 17, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02895-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02895-4