Abstract

Background

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a common problem. When surgical treatment is required, the intervention is typically decompression without fusion. Successful return-to-work (RTW) is a standard expectation with these limited procedures. Occasionally, the size or location of the disc herniation suggests the need for fusion, but the inability to RTW is a significant concern in these cases. The purpose of this study is to determine if the addition of lumbar fusion, as compared to decompression alone, will substantially diminish RTW in patients with lumbar disc herniation.

Methods

This is a longitudinal cohort study using prospectively collected data from the Quality and Outcomes Database (QOD). Patients with LDH, eligible to RTW (not retired, a student, or on disability) with complete 12-month follow-up data, were identified. Standard demographic and surgical variables, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and RTW status at 3 and 12 months were collected.

Results

Of the 5062 patients identified, 4560 (90%) had decompression alone and 502 (10%) had a concurrent fusion. Age and gender were similar in the two groups. The fusion group had worse back pain (NRS 6.52 vs. 5.96) and less leg pain (6.31 vs. 7.01) at baseline compared to the no fusion group. Statistically significant improvement in all PROs was seen in both groups. RTW at 3 months post-op was seen in 85% of decompression cases and 66% of cases with supplemental fusion. At 12 months post-op, RTW increased to 93% and 82%, respectively.

Conclusion

The need for fusion in LDH cases is unusual, seen in only 10% of cases in this series. The addition of fusion decreased the RTW rate from 85 to 66% at 3 months and from 93 to 82% at 12 months post-op. While the difference is significant, the ultimate deterioration in RTW may be less than anticipated. A reasonable RTW rate can still be expected in the rare patient who requires fusion as part of their treatment for LDH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a common pathology which is responsible for 20% of low back pain leading to disability and work absence [1]. The incidence of a herniated disc is 5 to 20 cases per 1000 adults annually. It is most common in people in their third to the fifth decade of life, with a male to female ratio of 2:1 [2]. Eighty-five percent of patients with an acute LDH improve spontaneously with conservative management [3]. NSAIDs and physical therapy are the first-line treatment modalities, followed by epidural injections [4].

When surgical treatment is required for a LDH, this usually occurs after at least 6 weeks of failed conservative treatment. The intervention is typically partial discectomy without fusion to alleviate radicular symptoms. Occasionally, the size or location of the disc herniation suggests a need for fusion. A far lateral disc herniation may require a significant resection of the facet joint, rendering that level unstable. There may be instances in which the decompression alone results in a significant loss of disc height. As the intervertebral disc is considered to be a biomechanical stabilizer of the spinal unit, the surgeon therefore may decide to proceed with fusion. Segmental instability after a discectomy is thought to be one of the risk factors for residual low back pain and recurrence of disc herniation [5, 6]. There may also be instances in which the patient might not be deemed to require fusion by most surgeons, but fusion is undertaken due to individual surgeon preference. Prior studies have examined the influence of financial incentives in the surgical decision-making process [7].

Successful return-to-work (RTW) is a standard expectation with decompression alone, whereas inability to RTW is a significant concern in those cases requiring decompression with fusion. To our knowledge, no study has compared the RTW of patients who underwent a decompression without fusion compared to a decompression with spinal fusion in LDH patients. The purpose of this study is to determine if the addition of lumbar fusion, as compared to decompression alone, will substantially diminish RTW 1 year after surgery in patients with LDH.

Materials and methods

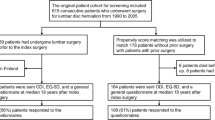

The Quality Outcomes Database (QOD) registry was queried in December 2018 for patients with lumbar disc herniation (LDH) who underwent operative treatment with either a decompression alone or a decompression with fusion. QOD is a prospective registry, established in 2012, that was designed to evaluate risk-adjusted expected morbidity and 12-month outcomes with the goal of providing insights into and ameliorating the efficiency and quality of care for the most commonly performed spinal surgical procedures in the USA [8, 9].

Patients who were included in the study were eligible to return to work (RTW). Those who were identified as retired, a student, or on disability were excluded. Other inclusion criteria were age greater or equal to 18, at least 1-year follow-up from surgery, and the procedure performed as a primary operation and not for a recurrent disc herniation.

Standard demographics included age, sex, BMI, and surgical variables including estimated blood loss, and total operating room time was also evaluated. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) at baseline, 3 and 12 months, were collected including back and leg pain numeric rating score (NRS) [10], Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) [11, 12], and RTW and if there were any associated worker’s compensation claims.

All statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (Armonk, New York). Baseline characteristics of the decompression alone and the fusion groups were compared using unpaired independent t tests for continuous data and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Repeated measures ANOVA with the baseline PRO score as a co-variate was used to compare PRO changes over time between the two groups. Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables was used to compare return to work rates between the two groups at 3 and 12 months after surgery. Binary logistic regression was performed to identify variables associated with return to work at 12 months. Statistical significance was set at p<0.01.

Results

Of the 5062 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 4560 (90%) had decompression alone and 502 (10%) had a concurrent fusion (Table 1). Age, gender, and BMI were similar in the two groups. The proportion of patients receiving Workers Compensation and the type of work prior to surgery was similar between the two groups. The fusion group had worse back pain (NRS 6.52 vs 5.96, p<0.001) but less leg pain (6.31 vs 7.01, p<0.001) at baseline compared to the no fusion group. EQ-5D and ODI scores were similar between the two groups.

The OR time was significantly greater in the fusion (172.53 min) vs the no fusion (75.54 min, p<0.001) group. The fusion group also had significantly more blood loss (249.44 mL) than the no fusion (49.82mL, p<0.001) group. Repeated measures ANOVA showed that the fusion group also had worse PROs through 3 and 12 months compared to the no fusion group even when adjusting for the differences in the baseline pain scores. The ODI was statistically similar at baseline in both groups (fusion 46.67 vs no fusion 47.39, p=0.688), and although both groups improved substantially, the fusion group demonstrated less improvement vs. the no fusion group at 12 months (23.28 vs 17.21, p=0.004).

At 3 months, 85% of the decompression-only patients had returned to work compared to 66% of the fusion group (p <0.001). At 12 months, this difference was still significant, decompression only group had 93% RTW and fusion only 82% RTW (p <0.001). Binary logistic regression analysis showed that type of employment prior to surgery, the performance of the fusion, and 12-month EQ-5D were associated with return to work at 12 months after surgery (Table 2). Age, gender, BMI, workers’ compensation, and baseline PRO scores were not associated with return to work at 12 months.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing RTW following decompression versus decompression with fusion for patients with primary LDH refractory to conservative treatment. Decompression alone is obviously the standard treatment in these cases, and only 10% of our study population underwent fusion. This nonetheless represents a substantial population for which the expected RTW rate is not well defined.

Several prior studies have examined RTW in the LDH population, but none have compared decompression only vs. fusion cases. Atarod et al. [13] reviewed 142 patients who underwent lumbar discectomy to determine the rate and contributing factors of return to work in the postoperative phase. They had 113 (79.5%) of patients return to work in 3 months. Predictive factors for RTW included male gender, higher literacy, non-manual job, non-smoker, formal work agreement, normal BMI, lower working hours, and higher income. Than et al. [14] followed 127 patients 3 months postoperatively from lumbar discectomy, and after controlling for patients who were working preoperatively (105 patients), only younger age was a statistically significant predictor of postoperative return to work (44.1 years vs 51.1 years, p = 0.049). In the present study, less physically demanding job, performance of a fusion, and 12-month EQ-5D scores were associated with return to work at 12 months. Although 12-month ODI scores were significantly associated, the odds ratio is close to 1.0 which denotes clinical irrelevance. In the present study, 85% of the decompression only patients had returned to work at 3 months post-op as compared to 66% of the fusion group (p <0.001). By 12 months post-op, this difference was diminished, but still significant with 93% RTW in the decompression group and 82% RTW in the fusion group (p <0.001).

Historically, back pain preoperatively along with radicular symptoms was an indication to perform concomitant fusion with decompression [15]. This is no longer the case, and decompression alone is now the standard treatment for LDH. However, fusion is still a useful adjuvant procedure in the properly screened patient. Vaughan et al. [16] evaluated the results of 85 patients, 52 with discectomy and 33 with discectomy and fusion and determined that the fusion group had significant better results compared to the non-fusion group (85% vs 39%). The only statistical significance in their preoperative values included duration of back pain (fusion 44.8 vs no fusion 23.3 months, p < .001), history of chronic back pain > 6 months (fusion 94% vs no fusion 52%, p <0.001), percentage of patients positive straight leg raise (fusion 88% vs no fusion 100%, p <0.02), and percentage narrow of L4–L5 disc space (fusion 76% vs no fusion 32%, p <0.001). The most common cause of unsatisfactory results in the fusion group was pseudarthrosis [2] while progressive degenerative disc disease [18] and recurrent disc prolapse [8] were the most common causes of unsatisfactory results in the discectomy group. Takeshima et al. [17] looked at 95 patients with lumbar disc herniation requiring surgery, 45 patients had discectomy, while 51 underwent discectomy and fusion. Clinical outcome was excellent or good in 73% of the non-fusion group and 82% of the fusion group (p =0.31), and patients with fusion had a greater reduction in back pain. This study suggests that if an appropriate patient is selected for fusion for LDH, they could have more positive outcomes.

Satoh et al. [5] looked at 498 patients with a minimum 5-year follow-up who underwent primary surgery at a single level for LDH. They set criteria for fusion as massive herniation and segmental instability. A massive herniation was defined as a complete block on myelogram, and segmental instability was defined as an anterior slip of > 3 mm or local kyphosis of > 5° on a lateral radiograph of maximal flexion. They had four groups: group one underwent fusion and met criteria for fusion; group two had an indication for discectomy only, but underwent fusion; group three had an indication for fusion but underwent discectomy only; and group four had an indication for a discectomy and underwent discectomy. There was no statistical significant difference in any group regarding outcomes of leg pain or low back pain.

The present study is not without limitations. First, this study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected registry data and holds the associated limitations. Secondly, our metric of employment status and RTW may lack granularity. Patients only able to return to part-time employment or modified duty remain a significant economic burden to employers, among others. Occasionally, non-physical factors such as motivation, job satisfaction, and financial advantages would have more effect on the decision to RTW than overall back pain and recovery [18]. There are also post-operative factors that are not accounted for in this data. Carragee et al. [19] lifted all post-operative activity restrictions on patients after microdiscectomy, which may also allow those patients to RTW faster. Routine practice with fusion typically limits bending, lifting, and twisting in patients who recently underwent fusion for up to 3 months.

Patients who underwent fusion in our study also had more back pain both pre- and post-operatively and less leg pain at baseline but worse leg pain at 12 months post-op compared to the non-fusion group. The back pain could be related to their original LDH or to a myriad of pre/post-patient factors that are not accounted for in this analysis. Wang et al. [20] evaluated 16/221 (7.2%) patients who experienced persistent low back pain following spinal fusion for LDH with a numeric rating scale (NRS) >50 at all post-operative follow-up time points. They determined that preoperative back pain (NRS >3.5), surgery segment at L5-S1, and large fatty infiltrate rate of the paraspinal muscles (>15%) were significant and independent factors associated with persistent back pain following decompression and fusion. These specific factors were not accounted for in our study and another limitation when comparing the fusion to the no fusion group.

In summary, although the differences in return to work in our decompression vs. fusion cohorts were statistically significant, by 12 months, the difference was relatively small (93% vs 82%). Return to work was slower in the fusion group, but ultimate return to work was better than most prior reports.

The need for fusion in LDH is unusual, only present in 10% of cases in this series. The addition of fusion does decrease RTW from 85 to 66% at 3 months and from 93 to 82% at 12 months postoperatively. While the difference is statistically significant, the value is only modestly impaired. Reasonable RTW can be expected in the rare patient who requires fusion for LDH, and providers should still use their clinical judgment to provide the best treatment option for each patient with the understanding that RTW rates should be acceptable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the NeuroPoint Alliance but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the NeurPoint Alliance.

Abbreviations

- RTW:

-

Return to work

- LDH:

-

Lumbar disc herniation

- QOD:

-

Quality Outcomes Database

- PROs:

-

Patient-reported outcomes

- NRS:

-

Numeric Rating Scale

- NSAIDS:

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Disablity Index

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQOL 5 Dimenstions

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- OR:

-

Operating room

References

Kitze K, Winkler D, Gunther L, et al. Preoperative predictors for the return to work of herniated disc patients. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2008;69(1):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-993174.

Fjeld OR, Grøvle L, Helgeland J, Småstuen MC, Solberg TK, Zwart JA, et al. Complications, reoperations, readmissions, and length of hospital stay in 34 639 surgical cases of lumbar disc herniation. Bone Joint J. 2019 Apr;101-B(4):470–7. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.101B4.BJJ-2018-1184.R1.

Carlson BB, Albert TJ. Lumbar disc herniation: what has the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial taught us? Int Orthop. 2019 Apr;43(4):853–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-019-04309-x.

Harper R, Klineberg E. The evidence-based approach for surgical complications in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Int Orthop. 2019 Apr;43(4):975–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4255-6.

Satoh I, Yonenobu K, Hosono N, Ohwada T, Fuji T, Yoshikawa H. Indication of posterior lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar disc herniation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006, Apr;19(2):104–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bsd.0000180991.98751.95.

Wang, J, Dailey, A, et al. Guideline update for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Part 8: lumbar fusion for disc herniation and radiculopathy. J Neurosurg Spine 2014. 21:48-53, 1, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.4.SPINE14271.

Whang PG, Lim MR, Sasso RC, Skelton A, Brown ZB, Greg Anderson D, et al. Financial incentives for lumbar surgery: a critical analysis of physician reimbursement for decompression and fusion procedures. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008 Aug;21(6):381–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0b013e31814d4e1b.

Asher AL, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Parker SL, Davies JM, Selden N, et al. The national neurosurgery quality and outcomes database (N2QOD): a collaborative North American outcomes registry to advance value-based spine care. Spine. 2014;39(22 Suppl 1):S106–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000579.

McGirt MJ, Parker SL, Asher AL, Norvell D, Sherry N, Devin CJ. Role of prospective registries in defining the value and effectiveness of spine care. Spine. 2014;39(22S):S117–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000552.

McCaffery M, Beebe A. Pain: a clinical manual for nursing practice. Baltimore: V.V. Mosby Company; 1993.

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–52.

Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66(8):271–3.

Atarod M, Mirzamohammadi E, Ghandehari H, Mehrdad R, Izadi N. Predictive factors for return to work after lumbar discectomy. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2019;24:1–6.

Than K, Curran J, Resnick D, et al. How to predict return to work after lumbar discectomy: answers from the NeuroPoint-SD registry. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;25(2):181–6. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.10.SPINE15455.

Murphey F. Sources and patterns of pain in disc disease. Clin Neurosurg. 1968;15(CN_suppl_1):343–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/neurosurgery/15.CN_suppl_1.343.

Vaughan PA, Malcolm BW, Maistrelli GL. Results of L4-L5 disc excision alone versus disc excision and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988 Jun;13(6):690–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-198813060-00018.

Takeshima T, Kambara K, Miyata S, Ueda Y, Tamai S. Clinical and radio- graphic evaluation of disc excision for lumbar disc herniation with and without posterolateral fusion. Spine. 2000;25(4):450–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200002150-00010.

Donceel P, Du Bois M, Lahaye D. Return to work after surgery for lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:872–6.

Carragee E, Han M, et al. Activity restrictions after posterior lumbar disectomy. A prospective study of outcomes of 152 cases with no post-operative restrictions. Spine. 1999;24(22):2346–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199911150-00010.

Wang H, Wang T, Wang Q, Ding W. Incidence and risk factors of persistent low back pain following posterior decompression and instrumented fusion for lumbar disc herniation. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1019–25.

Acknowledgements

No other person aside from the authors made substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data or was involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Funding

No funding was received for the design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the research design, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. LAP drafted the paper and provided critical revisions. All authors provided critical revision. The authors approved of the submitted and final versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board for Collection data for the Database (HSPPO#11.0246) and this analysis (HSPPO#18.1234); and the Norton Healthcare Office of Research Administration Board for Collection data for the Database (RO#11.n0113) and this analysis (RO#18.N0388)/.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or nonfinancial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge, or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Protzer, L.A., Glassman, S.D., Mummaneni, P.V. et al. Return to work in patients with lumbar disc herniation undergoing fusion. J Orthop Surg Res 16, 534 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02682-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02682-1