Abstract

Background

Emergency general surgery (EGS) patients account for more than one-third of admissions to hospitals in the National Health Service (NHS) in England. The associated mortality of these patients has been quoted as approximately eight times higher than that of elective surgical admissions. This study used a modified Delphi approach to identify research priorities in EGS. The aim was to establish a research agenda using a formal consensus-based approach in an effort to identify questions relevant to EGS that could ultimately guide research to improve outcomes for this cohort.

Methods

Three rounds were conducted using an electronic questionnaire and involved health care professionals, research personnel, patients and their relatives. In the first round, stakeholders were invited to submit clinical research questions that they felt were priorities for future research. In rounds two and three, participants were asked to score individual questions in order of priority using a 5-point Likert scale. Between rounds, an expert panel analysed results before forwarding questions to subsequent rounds.

Results

Ninety-two EGS research questions were proposed in Phase 1. Following the first round of prioritisation, forty-seven questions progressed to the final phase. A final list of seventeen research questions were identified from the final round of prioritisation, categorised as condition-specific questions of high interest within general EGS, emergency colorectal surgery, non-technical and health services research. A broad range of research questions were identified including questions on peri-operative strategies, EGS outcomes in older patients, as well as non-technical and technical influences on EGS outcomes.

Conclusions

Our study provides a consensus delivered framework that should determine the research agenda for future EGS projects. It may also assist setting priorities for research funding and multi-centre collaborative strategies within the academic clinical interest of EGS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients requiring emergency general surgery (EGS) are known to have a high risk of death and complications [1,2,3] with estimates suggesting they account for 50% of all surgical mortality [3]. The provision of EGS service is a global public health issue, which has made it an important area of research [4, 5]. In the UK, the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) projects have shown the benefits of research on quality improvement for EGS patients [6, 7].

With the emergence of EGS as an important area of clinical interest in need of service reconfiguration, there is growing momentum to address the challenges involved in the delivery of patient focused, safe and proficient care and to improve patient outcomes [8]. Identifying patient-centred research priorities has the potential to deliver clinically relevant questions that could guide funding and management strategies and prioritise resource allocation thereby strengthening standards of care provided within this speciality [9].

A modified Delphi process can be used to establish a consensus opinion on research priorities from a panel of experts within that field [10]. Using a participative approach and structured prioritisation methods, stakeholders can identify research that they believe will have the most meaningful impact on EGS care.

The aim of this research is to produce a peer-reviewed list of research priorities for EGS. The study was undertaken by members of the Scottish Surgical Research Group (SSRG) with organisational support provided by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) and Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (ASGBI).

Methods

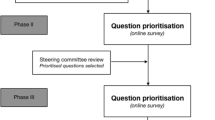

A modified Delphi technique was used to identify research priorities in EGS and build consensus across a group of stakeholders (Fig. 1). The Delphi method is an a priori, structured communication technique in which a group of experts reach a structured consensus on a topic through a number of rounds of questions with controlled feedback [11, 12]. In order to be General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant, formal consent was gained to use responses. Respondents were also given the opportunity to withdraw consent. Respondents were allocated an anonymous ID, and identifiable data were not publicised. Research ethical approval was not required for this study according to National Research Ethics Service guidance [11].

Stakeholder identification

A three-phased modified Delphi process was undertaken which included two phases of prioritisation by stakeholders using established methodology from other Delphi processes [12, 13].

The steering committee for this research consisted of five general surgery specialty trainees (EV, RP, JW, SK and HS) and nine consultant general surgeons (MW, DD, JC, SM, KM, CP, FC, GLB and GT), all of whom have an interest in EGS. The role of the steering committee was to ensure relevance of the submitted questions from both a clinical and patient perspective and to provide consensus agreement on amendments to submitted questions and cut-off points following prioritisation in Phases II and III.

Phase I

Stakeholders were invited to submit research questions relevant to the field of EGS using an electronic questionnaire (https://www.surveymonkey.com). Invitation emails were sent to the ASGBI and WSES membership. Twitter(R) (Twitter Inc., San Francisco, California) was also used to broaden the awareness of the Delphi process amongst interested stakeholders using a dedicated study account (@EmSurg_Delphi). There was no limit to the number of questions that an individual could submit. Questions were encouraged from doctors, nurses, allied health professionals as well as from patients who have undergone an EGS procedure or were admitted as an emergency under the care of a general surgeon. Phase I was open for 6 weeks.

Following submission of questions, a subcommittee categorised all questions into topics. These were EGS, emergency upper gastrointestinal surgery, emergency colorectal surgery, non-technical questions and health service questions. Duplicate questions were deleted. Questions with a similar theme were modified by consensus agreement, and care was taken not to alter the meaning of the questions.

Phase II

ASGBI and WSES members were invited by email containing a link to an online survey to prioritise the consensus agreed list of questions from Phase I. Twitter was again used to broaden the awareness of the study among stakeholders. Using a Likert scale, stakeholders ranked questions from 1 (lowest research priority) to 5 (highest research priority). The survey remained open for 6 weeks with 1 email reminder sent to ASGBI and WSES members. The results were reviewed by the subcommittee.

Questions that were scored as 4 or 5 by ≥ 55% stakeholders were progressed to the final round of prioritisation. A 55% cut-off was chosen, without sight of the questions, as there was a clear gap in scores for questions below this percentage. It also yielded a number of remaining questions regarded as manageable for use in Phase II.

Phase III

A final round of prioritisation was undertaken on the consensus agreed list of questions at the end of Phase II using the same methodology as before. A higher cut-off of 65% of questions being scored as 4 or 5 was agreed, again without sight of the questions for inclusion in the final list of prioritised questions. This phase stayed open for 6 weeks.

Results

In total, 108 stakeholders submitted 267 individual research questions in Round I. Following analysis and categorisation by the steering subcommittee, 92 questions were forwarded for inclusion in the first phase of prioritisation (see Appendix—Table 2). The composition of the initial stakeholders included consultant surgeons (n = 70), registrar/fellow/specialty doctor (n = 21), physicians (n = 11), patients (n = 3), Senior House Officers (n = 2), one medical student, and one pharmacist.

In the first phase of prioritisation, 92 questions were prioritised by 219 stakeholders (Appendix—Table 1). These included 196 EGS health care professionals, 11 patients and 12 others (including public and relatives). In the second phase of prioritisation, 41 questions from Phase I were ranked by 188 stakeholders (Appendix—Table 3). Following review by the steering committee, a final list of 17 prioritised research questions was agreed.

Discussion

Over the last decade, significant changes in the organisation, management and delivery of EGS services in units across the UK have resulted in improved service provision. A growing body of consultant surgeons with a special interest in EGS, combined with structural changes within these departments, have enabled the tailoring of strategic developments geared towards improving care for patients requiring EGS services. Many of these seismic shifts have been research driven. Studies reporting higher mortality rates with emergency laparotomies compared to elective cases, and others demonstrating wide variation in outcomes between trusts have highlighted the need for further research aimed at improving standards of care for emergency cases [1, 14, 15].

The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Deaths (NECPOD) [16] and the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) [6] were two studies designed to collect organised and comparative data on emergency service provision across the UK in an attempt to improve the quality of care for patients undergoing emergency surgery. The enhanced perioperative care for high-risk patients trial (EPOCH) [17] and the Emergency Laparotomy Collaborative (ELC) projects also focussed on areas in which patient outcomes could be improved. With approximately 25,000 patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery annually in NHS hospitals with 30-day mortality rates of 9.6% [7], national clinical projects like these are essential. The Emergency Laparoscopic and Laparotomy Scottish Audit (ELLSA) aimed to capture an even more comprehensive EGS cohort than NELA by widening the inclusion of contributing sites and including laparoscopic procedures [18]. To our knowledge, this study is the first Delphi undertaken in the field of EGS and is intended to guide this much needed research and stimulate health care quality improvement.

Our modified Delphi process has produced a list of 17 high-priority research questions in the field of EGS. We adopted a non-biased approach of inviting members of two established surgical societies (ASGBI and WSES), but also publicised on Twitter in order to ensure that members of the public and patients were able to participate. Figure 2 demonstrates heat maps of the distribution of respondents prioritising research questions in Phase II (A) and III (B), respectively. The input of the latter two groups was a valued addition, with the focus of many research areas identified relating to patient experience and patient-reported outcomes.

There are no defined criteria on setting cut-off consensus levels in Delphi studies [19]. Consensus levels are defined as a percentage higher than the average percentage of majority opinion [20], and many researchers have used different levels of agreement to achieve consensus. As the aim of our study was not to achieve a pre-determined consensus level, each phase of our Delphi was terminated based on subjective analysis of the number of questions remaining after each round. Following the first round of prioritisation, in the case of a 55% majority there was consensus on 41 questions, a 60% majority resulted in 23 questions and at 70% concordance 7 questions remained. To produce a manageable number of relevant questions, a majority view within the steering group chose a level of agreement of 55% for the first round of prioritisation. We chose a more strict criteria of 65% for the final list of questions, again to produce a manageable number of questions with the highest priority.

There were a number of questions that did not make the final list of prioritised questions. A ranked list of all questions is included in the Appendix (Table 3).

The Emergency Laparotomy and Frailty (ELF) study highlighted that 20% of patients undergoing emergent laparotomy in the UK are frail, presenting greater risk of post-operative morbidity and mortality, independent of age [21]. In the fourth patient report of NELA [7], researchers identified that despite evidence of improved outcomes with comprehensive geriatric assessment methodology [22], there was no improvement in the proportion of patients over the age of 70 benefiting from geriatric specialist input. This is reflected in our study. From our list of prioritised questions, a recurrent theme was consideration on focusing future research on the management of older adult and frail patients undergoing EGS.

Our final list of prioritised questions also included a significant emphasis on optimisation of EGS services and training. Further studies are also required to develop a greater understanding of optimisation of EGS patients peri-operatively, and research into technical considerations in emergency colorectal surgery is required to guide potential improvements in survival outcomes. The study’s results are particularly relevant in the current setting.

One major limitation we anticipated was that of survey fatigue—the tendency to not fully complete a survey when faced with several pages of questions, or reluctance to participate at all. To mitigate this, we designed the surveys with categories in reverse order between surveys.

Another limitation was the lack of patient input into this project, which risks avoiding the research areas which are of interest to patients. The intention of the study group was to hold a patient focus group at the end of Phase I. However, this was not possible as the timing coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and the first lockdown in the UK. It was therefore decided to abandon this aspect of the study in the interest of the safety of our patients and to focus on gathering the views of members within the EGS multidisciplinary care team. Though views of EGS patients and patients’ families were still sought, they did not yield many responses. Health charities and patient support groups are often keen participants in this type of research. However, there are relatively few EGS groups compared to conditions such as Crohn’s disease and colitis [23], or bowel cancer [24], highlighting that the EGS patient group is overlooked. There is clear scope to address this limitation of our study in the future.

A final limitation of EGS research to date is the overemphasis on mortality and morbidity as outcomes, which comprise a valuable future project.

We have used this modified Delphi method to survey multiple stakeholder groups including patients, health care providers and multidisciplinary team members involved in all aspects of EGS care provision. We believe that this is an important body of work that demonstrates consensus across a broad and diverse group of stakeholders. The findings of this study can be used to guide future research studies and research funding in the EGS community.

Conclusions

Seventeen high-priority research questions relevant to EGS have been identified by a consensus of EGS stakeholders by a modified Delphi process. This work should be used to focus future EGS research and funding and to encourage high-quality patient-centred multi-centre, international studies.

Availability of data and materials

Not relevant.

Abbreviations

- EGS:

-

Emergency General Surgery

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- NELA:

-

National Emergency Laparotomy Audit

- SSRG:

-

Scottish Surgical Research Group

- WSES:

-

World Society of Emergency Surgery

- ASGBI:

-

Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland

- GDPR:

-

General Data Protection Regulation

- ERAS:

-

Enhanced Recovery after Surgery

- HDU:

-

High-dependency unit

- ITU:

-

Intensive treatment unit

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

- NECOPD:

-

National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Deaths

- NELA:

-

National Emergency Laparotomy Audit

- EPOCH:

-

Enhanced Peri-operative Care for High-Risk Patients

- ELC:

-

Emergency Laparotomy Collaborative

- ELLSA:

-

Emergency Laparoscopic and Laparotomy Scottish Audit

- ELF:

-

Emergency Laparotomy and Frailty

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- POCUS:

-

Point-of-care ultrasound scan

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- MRCP:

-

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein (need to write this in words)

- FIT:

-

Faecal immunochemical testing (need to write this)

- NOACs:

-

Novel oral anticoagulants

- PR:

-

Per rectal

- US:

-

Ultrasound

- HPB:

-

Hepatobiliary

- UGI:

-

Upper gastrointestinal

References

Ramsay G, Wohlgemut JM, Jansen JO. Emergency general surgery in the United Kingdom: a lot of general, not many emergencies, and not much surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(3):500–6.

Ramsay G, Wohlgemut JM, Jansen JO. A 20-year study of in-hospital and post-discharge mortality following emergency general surgical admission. Br J Surg Open. 2019;3(5):713–21.

Havens JM, Neiman PU, Campbell BL, Croce MA, Spain DA, Napolitano LM. The future of emergency general surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;270(2):221–2.

Coccolini F, Kluger Y, Ansaloni L, et al. WSES worldwide emergency general surgery formation and evaluation project. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:13.

Wohlgemut JM, Ramsay G, Jansen JO. The changing face of emergency general surgery: a 20-year analysis of secular trends in demographics, diagnoses, operations and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2020;271(3):581–9.

NELA Project Team. First patient report of the national emergency laparotomy audit. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists; 2015.

NELA Project Team. Fourth patient report of the national emergency laparotomy audit. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists; 2018.

Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland, Association of Surgeons of Great Britain & Ireland. The future of emergency general surgery. A joint document. 2015. http://www.augis.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/05/Future-of-EGS-joint-document_Iain-Anderson_140915.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2021.

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gulmezoglu AM, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–65.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376–80.

www.hra.nhs.uk. Accessed 5 Feb 2021.

Allan M, Mahawar K, Blackwell S, Catena F, Chand M, Dames N, et al. COVID-19 research priorities in surgery (PRODUCE study): a modified Delphi process. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):e538–40.

Tiernan J, Cook A, Geh I, George B, Magill L, Northover J, et al. Use of a modified Delphi approach to develop research priorities for the association of coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(12):965–70.

Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–65.

Clarke A, Murdoch H, Thomas MJ, Cook TM, Peden CJ. Mortality and postoperative care after emergency laparotomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:16–9.

Ozdemir BA, Sinha S, Karthikesalingam A, et al. Mortality of emergency general surgical patients and associations with hospital structures and processes. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116:54–62.

Peden CJ, Stephens TJ, Martin G, et al. Effectiveness of a national quality improvement programme to improve survival after emergency abdominal surgery (EPOCH): a stepped- wedge cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2019;393:2213–21.

ELLSA Project Team. The first national report of the Emergency Laparoscopic and Laparotomy Scottish Audit (ELLSA). Scottish Government; 2019.

von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2012;79(8):1525–36.

Saldanha J, Gray R. The potential for British coastal shipping in a multimodal chain. Marit Policy Manag. 2002;29:77–92.

Parmar KL, Law J, Carter B, Hewitt J, Boyle JM, Casey P, Maitra I, Farrell IS, Pearce L, Moug SJ. Frailty in older patients undergoing emergency laparotomy: results from the UK Observational Emergency Laparotomy and Frailty (ELF) Study. Ann Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003402.

Eamer G, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to a surgical service. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD012485.

https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/support Accessed 12 Feb 2021.

https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk Accessed 12 Feb 2021.

Acknowledgements

The Scottish Surgical Research Group would like to thank the ASGBI and WSES for their support and administrative assistance throughout this study, in particular Bhavnita Patel and Vicki Grant who provided invaluable support at all stages of the study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MSJW and EMV conceived the project. EMV, RP, JMW, SRK and MSJW collected the data. All authors analysed the data. EMV and JMW prepared the manuscript. All authors provided critical analysis and approval of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required as no patients involved.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the manuscript and given consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaughan, E.M., Pearson, R., Wohlgemut, J.M. et al. Research priorities in emergency general surgery (EGS): a modified Delphi approach. World J Emerg Surg 17, 33 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00432-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00432-0