Abstract

Background

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is still ongoing and a major challenge for health care services worldwide. In the first WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey, a strong negative impact on emergency surgery (ES) had been described already early in the pandemic situation. However, the knowledge is limited about current effects of the pandemic on patient flow through emergency rooms, daily routine and decision making in ES as well as their changes over time during the last two pandemic years. This second WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey investigates the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on ES during the course of the pandemic.

Methods

A web survey had been distributed to medical specialists in ES during a four-week period from January 2022, investigating the impact of the pandemic on patients and septic diseases both requiring ES, structural problems due to the pandemic and time-to-intervention in ES routine.

Results

367 collaborators from 59 countries responded to the survey. The majority indicated that the pandemic still significantly impacts on treatment and outcome of surgical emergency patients (83.1% and 78.5%, respectively). As reasons, the collaborators reported decreased case load in ES (44.7%), but patients presenting with more prolonged and severe diseases, especially concerning perforated appendicitis (62.1%) and diverticulitis (57.5%). Otherwise, approximately 50% of the participants still observe a delay in time-to-intervention in ES compared with the situation before the pandemic. Relevant causes leading to enlarged time-to-intervention in ES during the pandemic are persistent problems with in-hospital logistics, lacks in medical staff as well as operating room and intensive care capacities during the pandemic. This leads not only to the need for triage or transferring of ES patients to other hospitals, reported by 64.0% and 48.8% of the collaborators, respectively, but also to paradigm shifts in treatment modalities to non-operative approaches reported by 67.3% of the participants, especially in uncomplicated appendicitis, cholecystitis and multiple-recurrent diverticulitis.

Conclusions

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic still significantly impacts on care and outcome of patients in ES. Well-known problems with in-hospital logistics are not sufficiently resolved by now; however, medical staff shortages and reduced capacities have been dramatically aggravated over last two pandemic years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since the World Health Organization has declared SARS-CoV-2 as a worldwide pandemic in early 2020, it dominates daily life and influences political decisions as well as daily therapeutic practices in various medical disciplines. Global or local lockdown policies and recommendations regarding postponement of elective therapies during the last two pandemic years aim at providing necessary health care capacities especially during wave-like outbreaks of different variants of SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, the discussion behind postponements of elective surgical therapies is primarily to hold up bed, intensive care as well as operating room capacities available during the pandemic and secondarily to preserve patients and medical staff from nosocomial infection with SARS-CoV-2 [1,2,3,4]. However, postponement of elective surgical therapies might not be detrimental in the short-term follow-up upon diagnosis, but delayed treatments might have some harmful effects beyond that short range in the longer-term outcome [2]. This it is quite clear for surgical oncology, because delays in cancer-specific therapy might result in severely impaired oncologic outcome [2, 5,6,7].Even patient outcome is impaired through postponements of elective surgical therapy of other non-malignant diseases during the pandemic [8]. The situation is dramatically different in emergency patients. Postponement of urgent therapies is not allowed in the emergency setting and can rapidly result in detrimental outcome [9, 10]. However, local hospital management for maintaining an adequate emergency surgical service during wave-like SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks with high incidences of severely-ill COVID-19 patients and limited intensive care capacities is challenging. Policies, health care providers and hospital management have to balance the necessity of strong SARS-CoV-2 measures on the one hand and the maintenance of surgical emergency services on the other hand, which both compete with critical hospital resources including normal ward, intensive care and operating room capacities as well as personnel required for an adequate therapy and additional expenses for quarantine measures.

Since the rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 around the world in late 2019, a high amount of research had been published regarding the pandemic, the characteristics of the virus and treatment modalities of COVID-19, which are urgently needed [4]. However, the literature reveals some evidence about dramatic negative effects of the pandemic on various medical fields and health care services, e.g., in oncology, cardiovascular diseases, etc., as well as on the outcome of respective patients [5, 11,12,13,14]. By now, this list is endless and the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has obviously a negative impact on emergency surgery worldwide: Although case load decreases, patients present with more severe and prolonged surgical emergencies, and thus, treatment is more complex and surgery is more complicated during the pandemic [3, 15, 16].

As a consequence, these pandemic-driven factors uncertainly influence not only the entire spectrum of elective patient care, but also have a significant effect on daily routine patient care in emergency rooms and particularly in emergency surgery. However, the knowledge is limited about the impact of the pandemic on patient flow through emergency rooms, clinical daily routine and clinical decision making in emergency surgery as well as their changes over time during the last two years of the pandemic. In our first WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey from June 2020, we have described a strong impact of the pandemic on emergency surgery services worldwide due to potential harmful delays in time-to-diagnosis (TTD) and time-to-intervention (TTI), and the need of triage of emergency surgical patients [3]. Data analysis revealed that structural problems like in-hospital logistics were predominantly responsible for negative effects of SARS-CoV-2 on emergency surgical patient care [3]. This new second WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey investigates the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on patients and their diseases requiring emergency surgery, on TTD and TTI in emergency departments as well as relevant causes for a delayed surgical therapy during the course of the pandemic. Two years after the initial survey structural rearrangement, new in-hospital standard operating procedures and integration of SARS-CoV-2 into the everyday clinicians’ work should have led to an improvement of emergency care. If the initial problems persist, this must lead to a radical and immediate improvement of surgical emergency care worldwide.

Methods

An online survey was designed by a core group of investigators of the study group. Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, California, USA) was used as the platform for the survey.

The survey was designed, the survey study was conducted, and the results were analyzed and reported following the CHERRIES statement [17].

The survey consists of multiple-choice and single-choice items as well as open-answer questions. In the style of the first WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey study from June 2020, published in December 2020 [3], the items of the present questionnaire are organized in five sections: (1) recording the characteristics of collaborators and their affiliated hospitals, (2) evaluating the experiences of the study group with emergency surgery in COVID-19-infected patients, (3) investigating the ongoing impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on patients requiring emergency surgery as well as (4) ongoing structural problems caused by the pandemic and leading to substantial barriers across emergency surgical pathways and quality loss in emergency patient treatment. Furthermore, (5) individual experiences with septic diseases potentially requiring intensive care, interventional emergency therapy and/or emergency surgery as well as (6) potential paradigm shifts from a standard operative therapy before the pandemic situation to a non-operative (conservative) treatment approach during the pandemic and (7) preventive, quarantine and SARS-CoV-2 testing strategies are part of the survey.

After the survey was approved by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) project steering committee, this cross-sectional survey study was distributed on January 17, 2022, to the global mailing list of WSES members and beyond, as addressees were invited to distribute the survey to their colleagues. The survey was closed after four weeks on February 11, 2022.

After closing the survey, the results were checked for duplicates. Results are presented descriptively within the present manuscript.

Results of items, that were comparable with our previous WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey study from June 2020 [3], were conducted to statistical analyses, which allowed us to investigate changes in responses over time during the pandemic situation. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 9 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). For descriptive statistics, categorical data were analyzed using Fishers exact test or Pearson’s X2 test. p values ≤ 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Because of the exploratory character of the study, no adjustments of p values were performed.

Data are given as n collaborators and/or percentages of the collaborators.

Results

Characteristics of participants and their affiliated hospitals

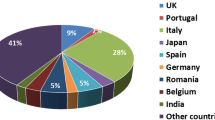

367 health care specialists in emergency medicine and emergency surgical patient care from 59 countries around the world, i.e., 5 continents, completed the survey study (Fig. 1). Most participants work in a larger public, third-level (academic/referral) hospital with more than 500 beds (Fig. 2) which includes a dedicated emergency department (96.2% of the cases) and more precisely a dedicated acute care surgery or emergency surgery unit at the own hospital (71.9% of the cases). With 86.9% and 15%, most collaborators came from general/abdominal surgery and trauma surgery/orthopedics, respectively, but representatives of other medical disciplines, which are involved in emergency surgical patient care, were also represented in the study cohort including internal medicine, anesthesiology, vascular surgery, thoracic surgery and gynecology (all < 5%). Therefore, most of the collaborators are well-experienced personnel with being senior consultants and heads of the departments in 48.0% and 19.3%, respectively, or at least board-certified staff in 18.3% (Fig. 1).

93.5% of the participants stated that they formally experienced three or more SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks in their region since the beginning of the pandemic situation in early 2020 (Fig. 3) and almost all collaborators (94%) stated that their region currently (from October 2021 to February 2022) suffers from a wave-like SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. In general, COVID-19 patients are treated in hospitals of 93.7% of the collaborators (Fig. 2) and almost all of the collaborators (88%) had performed emergency surgery in patients, acutely infected with SARS-CoV-2, which represents a significant increase over time compared with the situation in June 2020 (versus 62.2%, p < 0.0001 [3]). Interestingly, in hospitals of 13 participants (3.5%) emergency surgical patient care was interrupted due to the pandemic. Relevant or very relevant reasons for a discontinuous emergency surgery service among these participants were: reduced capacities on normal ward (69.2%) and intensive care units (76.9%), lack of nursing (76.9%) and medical staff (61.5%) as well as staff members being in quarantine or infected (53.8%, Fig. 3).

Ongoing impact of the pandemic on capacities and quality indicators of emergency surgery

In the previous WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey in June 2020, we reported that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic negatively influences the treatment of surgical emergency patients strongly [3]. Therefore, 83.1% of the collaborators indicated now that the pandemic still has an impact on treatment of surgical emergency patients and estimated this impact as being strong or very strong in 33.8% of the cases (Fig. 4). Interestingly, 18 of the 23 participants, from hospitals, which are not involved in care of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients, also observe these negative effects. However, the negative impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on emergency surgical services due to the pandemic was fortunately reduced over time compared with answers from the first WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey in June 2020, where almost 65.5% of the participants estimated it as being strong or very strong (p < 0.0001 [3]). Overall 44.7% of the participants still observe a decrease in emergency surgical cases in their hospitals compared with the situation before the pandemic (versus 86.2% of the collaborators from the previous WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey in June 2020, p < 0.0001 [3]). However, 74.1% of the participants reported this effect being mostly obvious during local lockdown policies.

Important quality indicators for emergency patient care are TTD and TTI. In the current survey, 52.6% and 50.1% of the participants still observe a delay in TTD and consecutively in TTI, respectively, due to the pandemic, which was comparable with the situation in June 2020 (p = 0.0734 and p = 0.2331 [3]). Even no obvious differences were seen in the estimated delays in TTD (p = 0.3763 [3]) and TTI (p = 0.0582 [3]) over time during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. To evaluate relevant factors being critical in the therapy of surgical emergency patients and why the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic might have an ongoing impact on emergency room and emergency surgical pathways, the collaborators of the study were asked for the most important factors that still lead to an enlarged TTD and TTI as well as problems with capacities concerning emergency surgery during the pandemic situation. The answers are summarized in Figs. 5e and 6. Interestingly, we did not observe improvements in in-hospital logistics, e.g., for transport of emergency patients or separated pathways for SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, reported over time from the previous WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey in June 2020 until now (p = 1 [3]), which is until now one of the most important problems for delays in TTD and TTI. Vice versa, significantly more collaborators currently report a dramatic lack in medical staff, especially in the operating room, leading to both unavailable operating room and intensive care unit capacities (all of them p < 0.0001 in comparison with the responses from the first WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey in June 2020 [3]), indicating that staff shortages and reduced capacities, relevant for emergency surgery, are dramatically aggravated during the course of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic over the last two years. These problems with limited local capacities continuously result in a relevant need of triage or transferring surgical emergency patients to other hospitals for further therapy, reported by 64% and 48.8% of the collaborators, respectively. Figure 6 reports free-text answers from the collaborators collecting further factors, which lead to problems with surgical emergency patient care during the pandemic.

Delays in surgical emergency patient care. Do the collaborators still observe delays in time-to-diagnosis (a, b) and time-to-intervention (c, d) in emergency surgery and the reasons behind these observations (e). #Lack of diagnostic capacities (e.g., computed tomography, endoscopy, etc.). §Persistent worse in-hospital logistics (e.g., transport of patients, closed normal wards, etc.)

Ongoing impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on diseases requiring critical care, emergency therapy, emergency surgery

The collaborators of the current WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey observed an ongoing medium, high or very high increase in relative numbers of severe (septic) abdomino-thoracic diseases, especially of perforated appendicitis and diverticulitis, during the pandemic in comparison with the situation before (Fig. 7a); however, this was comparable with the estimation of the participants from June 2020 (perforated appendicitis: p = 0.5586 and perforated diverticulitis: p = 1328 [3]). Contrastingly, two-thirds of the collaborators (67.3%) reported their experience that the pandemic situation (with reduced capacities, higher perioperative risk, etc.) led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of more uncomplicated infectious diseases to a non-operative approach. These findings are underlined by the reports upon the questions, which non-operative treatment options the participants recommend to their patients during the ongoing pandemic situation. This was mostly obvious for acute, uncomplicated infectious diseases including appendicitis and diverticulitis, but also more complicated diseases were considered to more conservative treatment modalities during the pandemic by a remarkable proportion of participants. Therefore, patient characteristics play an important role in these treatment considerations (Fig. 8).

Paradigm shift in treatment modalities. Shift of treatment modalities due to the pandemic from a frequently intended surgical therapy before to a non-operative approach during the pandemic situation in patients with appendicitis (a, b), diverticulitis (c–e) and cholecystitis (f). #multiple answers possible

In a conclusion, most of the collaborators think that the pandemic situation and its effects on emergency surgical patient care have a moderate (31.9%), severe (34.1%) or very severe (12.5%) negative impact on emergency surgical patient outcome. Only 13.4%, 7.6% and 0.5% of the participants think that this negative impact on patient outcome in the surgical emergency setting due to pandemic-driven changes is low, very low or zero, respectively (Fig. 7b). Interestingly, all participants, from hospitals, which are not involved in care of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients (n = 23), also estimated a moderate (n = 12), severe (n = 9) or very severe (n = 2) negative impact on the outcome of emergency surgical patients.

Preventive and testing strategies

In the hospitals of 78.7% of the collaborators, every patient entering the surgical emergency unit undergoes SARS-CoV-2 testing and 71.4% put patients in quarantine generally, if testing results are outstanding (Fig. 9). Therefore, “rapid” SARS-CoV-2-PCR is available at the surgical emergency unit of 76.3% of the participants for urgent results within one hour. 89.4% of the collaborators reported that their hospitals provide separated pathways for SARS-CoV-2 positive patients to minimize contact with uninfected patients. The most commonly used measures are closed areas and reserved rooms at the emergency unit, normal wards and intensive care units as well as reserved operating theatres for SARS-CoV-2 positive patients.

Testing and quarantine strategies. Local testing (a) and quarantine strategies (b) varying strongly. (c) Which separated pathways are useful and which resources are provided by hospital management to separate SARS-CoV-2 positive from uninfected patients. #multiple answers possible. §Reserved diagnostic facilities (e.g., computed tomography scanner, ultrasonography, etc.)

Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has still devastating effects on surgical emergency services worldwide. Our initial WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey from June 2020 revealed in the very early pandemic phase that there is a strong impact of the pandemic situation on surgical emergency patient care including potential harmful delays in TTD and TTI. This led either to a delayed therapy or the urge of triage of surgical emergency patients in a relevant proportion worldwide [3]. At that early time point, structural problems with in-hospital logistics were mainly responsible for these problems in patient care, whereas medical staff shortages previously did not play a major role contributing to these challenges in emergency surgery [3]. The current cross-sectional survey reflects the situation with emergency surgical patient care presently, approximately 2 years after. By now, the pandemic is still ongoing and various regions of the world suffered from numerous wave-like outbreaks of diverse variants of SARS-CoV-2. However, beyond several heterogeneous strategies to maintain global health care during the pandemic including social lockdown policies, adjusted treatment recommendations and in-hospital quarantine measures, the negative effect of the pandemic situation on surgical emergency patient care and on patient outcome is still significant. These alarming findings are underlined by persistent delays in TTD and TTI for emergency surgical patients during the last two years of the pandemic, which had been reported by approximately 50% of the collaborators. Therefore, it is well known that rapid initiation of diagnostics and therapy especially for patients with septic diseases in emergency surgery and trauma patients is mandatory for good treatment quality [9, 10, 18,19,20]. Furthermore, the collaborators were asked for relevant reasons causing the significant impact of the pandemic situation on emergency surgery: Persistent problems with in-hospital logistics are still major factors making an adequate surgical emergency treatment impossible. Obviously, these problems could not be resolved during the two-year lasting pandemic situation. Based on the results of the first WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey in 2020, we declared critical impairments in the diagnostic and therapeutic work-up of surgical emergency patients as a worldwide issue and postulated that improvements in care of surgical emergency patients like tailored solutions for in-hospital logistics are urgently necessary [3, 21]. Furthermore, we then hypothesized that proactive provision of resources to enhance medical staff, operating room capacities, intensive care capacities from policies, medical societies and local health care providers are mandatory for future patient care during the pandemic [3, 21]. In contrast, the situation in surgical emergency units worldwide is aggravated by dramatic shortages in medical staff, capacities and resources, which consecutively deteriorates the problematic situation with surgical emergency patients during the pandemic. Both the well-known logistic problems paired with the “new” lack of (human) resources summit in an enlarged TTD and TTI in many cases and finally to impaired outcome of our patients by now. Nevertheless, one has to keep in mind that some of these culprits, especially those logistic ones, might be modifiable easily, which might lead to significant improvements in in-hospital emergency patient care.

Another important aspect of the pandemic situation are changes in patient flow into the surgical emergency departments and changes in the disease quality requiring emergency surgery over the last two years. Overall a decreasing case load of emergency surgical patients is reported since the beginning of the pandemic in both WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery surveys [3]. But, an increase in more severe and prolonged diseases, including perforated appendicitis and diverticulitis, requiring more complex surgical or multimodal treatment strategies has been observed. Although it is a subjective estimation from the participants of the present survey, this finding is not entirely novel and had also been described by other authors from larger scaled cross-sectional studies involving patient data in the literature before. Although overall patient numbers are decreasing, especially patients with bowel diseases including appendicitis and diverticulitis present in the emergency rooms with more severe, prolonged and even perforated diseases [3, 8, 15, 16]. Besides that, Tebala et al. showed in their international retrospective cohort audit correlations of hospital admissions with general patient condition and physical health [22]. These changes in patient flow into surgical emergency departments as well as the observation of higher proportion of patients with more severe and prolonged diseases might be an expression of ongoing changes in medical evaluation and decision-making processes and a kind of pandemic-driven fear reactions of patients and referring physicians against SARS-CoV-2 infection [23]. Other issues, indicating changes in medical evaluation and particularly in decision-making processes, are paradigm shifts in the treatment modalities of frequent infectious diseases, which classically require (general) emergency surgery. Particularly in acute appendicitis, multiple recurrent and symptomatic non-complicative diverticulitis and cholecystitis a great proportion of participants would refer on a non-operative management, which—vice versa—was not regularly the case before the pandemic [24]. Additionally, some participants of the survey stated to apply non-operative therapeutic strategies for other severe septic diseases, including primary drainage therapy for perforated peptic ulcer in higher aged and polymorbid patients and prolonged drainage therapy to avoid—if possible—decortication for pleural empyema. If these circumstances will change treatment perceptions and therapeutic standards beyond the special situation during the pandemic remains to be seen in the future, however, emergency surgeons have to be aware that discussions are ongoing regarding more conservative treatment strategies in selected cases especially with appendicitis and diverticulitis.

In contrast, patients with traumatic emergencies frequently do not tolerate treatment postponements or conservative therapy attempts. The estimation of the collaborators, that the pandemic results in impaired outcomes of emergency surgical patients, underlines the essential necessity to maintain adequate and continuous patient care within the emergency setting including sufficient in-hospital and personnel capacities as well as appropriate in-hospital logistics. The latter includes fast SARS-CoV-2 testing (79% of the participants are testing every patient entering the surgical emergency room) and consequent quarantine measures with closed and reserved areas for patients with doubted or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection as highly important strategies on the one hand to prevent patients from misdiagnosis and delayed initiation of adequate therapy. On the other hand, these measures are mandatory to prevent patients and medical staff from nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection during high-incidence periods, which would worsen shortages in emergency surgical patient care, exhaustion and psychological pressure of personnel dramatically.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic still has a significant and global impact on care and outcome of surgical emergency patients. Well-known problems with in-hospital logistics are not sufficiently resolved by now; however, medical staff shortages and reduced capacities have been dramatically aggravated during the pandemic situation over the last two years. Global strategies to maintain adequate emergency surgical patient care are urgently needed from policies and hospital management [21]. These measures are not only mandatory during the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and future outbreaks of virus variants but also for prospective disaster management protocols.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

08 July 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00442-y

Abbreviations

- CHERRIES:

-

The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys

- COVID-19:

-

Corona virus disease 2019

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus type 2

- TTD:

-

Time-to-diagnosis

- TTI:

-

Time-to-intervention

- WSES:

-

World Society of Emergency Surgery

References

COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2021;2021(76):748–58.

Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, Costantini M, Salvador R, Merigliano S, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180–8.

Reichert M, Sartelli M, Weigand MA, Doppstadt C, Hecker M, Reinisch-Liese A, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on emergency surgery services-a multi-national survey among WSES members. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:64.

Noll, J., Reichert, M., Dietrich, M. et al. When to operate after SARS-CoV-2 infection? A review on the recent consensus recommendation of the DGC/BDC and the DGAI/BDA. Langenbecks Arch Surg (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02495-8

Kamarajah SK, Markar SR, Singh P, Griffiths EA. The influence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on esophagogastric cancer services: an international survey of esophagogastric surgeons. Dis Esophagus. 2020.

Pellino G, Spinelli A. How coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak is impacting colorectal cancer patients in Italy: a long shadow beyond infection. Dis Colon Rectum United States. 2020;63:720–2.

Stöss C, Steffani M, Pergolini I, Hartmann D, Radenkovic D, Novotny A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical oncology in Europe: results of a European survey. Dig Surg. 2021;38:259–65.

Willms A, Lock JF, Simbeck A, Thasler W, Rost W, Hauer T, et al. The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on care for elective patients (C-elective study)—results of a multicenter survey. Zentralbl Chir Germany. 2021;146:562–9.

Hecker A, Schneck E, Rohrig R, Roller F, Hecker B, Holler J, et al. The impact of early surgical intervention in free intestinal perforation: a time-to-intervention pilot study. World J Emerg Surg England. 2015;10:54.

Hecker A, Reichert M, Reuss CJ, Schmoch T, Riedel JG, Schneck E, et al. Intra-abdominal sepsis: new definitions and current clinical standards. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2019;404:257–71.

Nef HM, Elsässer A, Möllmann H, Abdel-Hadi M, Bauer T, Brück M, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular mortality and catherization activity during the lockdown in central Germany: an observational study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110:292–301.

McIntosh A, Bachmann M, Siedner MJ, Gareta D, Seeley J, Herbst K. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on hospital admissions and mortality in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11: e047961.

Kocatürk E, Salman A, Cherrez-Ojeda I, Criado PR, Peter J, Comert-Ozer E, et al. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management and course of chronic urticaria. Allergy Denmark. 2021;76:816–30.

Biagioli V, Albanesi B, Belloni S, Piredda A, Caruso R. Living with cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic: an Italian survey on self-isolation at home. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;30: e13385.

Willms AG, Oldhafer KJ, Conze S, Thasler WE, von Schassen C, Hauer T, et al. Appendicitis during the COVID-19 lockdown: results of a multicenter analysis in Germany. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2021;406:367–75.

O’Brien CM, Jung K, Dang W, Jang H-J, Kielar AZ. Collateral damage: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on acute abdominal emergency presentations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:1443–9.

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6: e34.

Reichert M, Hecker M, Witte B, Bodner J, Padberg W, Weigand MA, et al. Stage-directed therapy of pleural empyema. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg Germany. 2017;402:15–26.

Oppelt PU, Askevold I, Hörbelt R, Roller FC, Padberg W, Hecker A, et al. Trans-hiatal herniation following esophagectomy or gastrectomy: retrospective single-center experiences with a potential surgical emergency. Hernia. France; 2021.

Reichert M, Pösentrup B, Hecker A, Schneck E, Pons-Kühnemann J, Augustin F, et al. Thoracotomy versus video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) in stage III empyema-an analysis of 217 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc Germany. 2018;32:2664–75.

Coccolini F, Sartelli M, Kluger Y, Pikoulis E, Karamagioli E, Moore EE, et al. COVID-19 the showdown for mass casualty preparedness and management: the Cassandra Syndrome. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:26.

Tebala GD, Milani MS, Bignell M, Bond-Smith G, Lewis C, Cirocchi R, et al. Emergency surgery admissions and the COVID-19 pandemic: did the first wave really change our practice? Results of an ACOI/WSES international retrospective cohort audit on 6263 patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17:8.

Snapiri O, Rosenberg Danziger C, Krause I, Kravarusic D, Yulevich A, Balla U, et al. Delayed diagnosis of paediatric appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1672–6.

Reinisch A, Reichert M, Hecker A, Padberg W, Ulrich F, Liese J. Nonoperative antibiotic treatment of appendicitis in adults: a survey among clinically active surgeons. Visc Med. 2020;36:494–500.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all collaborators of the study for participation in the survey.

The WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey collaboration group (only those who agree are listed as collaborators)

Adam Peckham-Cooper, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom

Adrian Camacho-Ortiz, Hospital Epidemiology and Infectious diseases, Hospital Universitario Dr. José Eleuterio Gonzalez, Monterrey, Mexico

Aikaterini T. Mastoraki, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laikon Hospital, Greece

Aitor Landaluce-Olavarria, Alfredo Espinosa Urduliz Hospital, Spain

Ajay Kumar Pal, King George's Medical University, India

Akira Kuriyama, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Japan

Alain Chichom-Mefire, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon

Alberto Porcu, Università degli Studi di Sassari, Italy

Aleix Martínez-Pérez, Department of General and Digestive Surgery, Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset, Valencia, Spain

Aleksandar R. Karamarkovic, Surgical Clinic "Nikola Spasic" - UCC Zvezdara Belgrade, Faculty of Medicine University of Belgrade, Serbia

Aleksei V. Osipov, Department of urgent surgery, Scientific research institute of emergency medicine, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

Alessandro Coppola, General Surgery, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Italy

Alessandro Cucchetti, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences - DIMEC; University of Bologna, Italy

Alessandro Spolini, UOC Chirurgia Generale Sondrio ASST Valtellina-Alto Lario, Italy

Alessio Giordano, General Surgery unit, Nuovo Ospedale S. Stefano, Prato, Italy

Alexander Reinisch-Liese, Department of General, Viszeral and Oncologic Surgery, Klinikum Wetzlar,Teaching Hospital of JLU Giessen, Wetzlar, Germany

Alfie J. Kavalakat, Jubilee Mission Medical College & RI, Thrissur, India

Alin Vasilescu, Department of Surgery, St Spiridon University Hospital, “Grigore T Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi, Romania

Amin Alamin, General surgery department, Ealing Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, United Kingdom

Amit Gupta, Department of Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Rishikesh, Rishikesh, India

Ana Maria Dascalu, Faculty of Medicine, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Bucharest, Romania

Ana-Maria Musina, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Grigore T. Popa Iasi/ Regional Institute of Oncology Iasi, Romania

Anargyros Bakopoulos, Department of Surgery, Attikon University Hospital, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Andee Dzulkarnaen Zakaria, Department of Surgery, School of Medical Sciences & Hospital USM, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Andras Vereczkei, Department of Surgery, Medical Center, University of Pécs, Hungary

Andrea Balla, UOC of General and Minimally Invasive Surgery, Hospital “San Paolo”, Largo Donatori del Sangue 1, Civitavecchia, Rome, Italy

Andrea Bottari, Chirurgia dell'Apparato Digerente, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Careggi, Firenze, Italy

Andreas Baumann, Neurosurgical Department, Cologne Merheim Medical Center, Universitiy of Witten Herdecke, Germany

Andreas Fette, PS_SS, Weissach im Tal, Germany

Andrey Litvin, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Regional Clinical Hospital, Kaliningrad, Russia

Aniella Katharina Reichert, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital of Giessen, Giessen, Germany

Anna Guariniello, Emergency Surgery Ravenna Hospital, Italy

Anna Paspala, Evgenideio Hospital, Athens, Greece

Anne-Sophie Schneck, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de la Guadeloupe, Guadeloupe

Antonio Brillantino, Emergency Surgery Department, "A. Cardarelli" hospital, via Cardarelli 9, 80131 Naples, Italy

Antonio Pesce, AUSL of Ferrara - University of Ferrara, Italy

Arda Isik, Istanbul medeniyet university, Turkey

Ari Kalevi Leppäniemi, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Finland

Aristeidis Papadopoulos, General Hospital of Nikaia, Greece

Aristotelis Kechagias, Department of General Surgery, Kanta-Häme Central Hospital, Finland

Ashraf yehya abdalla Mohamed, General Surgery Department, Buraimi Hospital, Buraimi, Oman

Ashrarur Rahman Mitul, Bangladesh Shishu Hospital & Institute, Bangladesh

Athanasios Marinis, Third Department of Surgery, Tzaneio General Hospital, Piraeus, Greece

Athanasios Syllaios, Laiko General Hospital, Greece

Baris Mantoglu, Sakarya Medical Faculty, Turkey

Belinda De Simone, Department of Emergency, digestive and metabolic minimally invasive surgery, Poissy and Saint Germain en Laye Hospitals, France

Benjamin Stefan Weiss, Department for Adult and Pediatric Cardiovascular Surgery, University Hospital of Giessen, Giessen, Germany

Bernd Pösentrup, Department of Pediatric Surgery and Pediatric Urology, Children´s Hospital, Klinikum Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany

Biagio Picardi, San Filippo Neri ASL Roma 1, Italy

Biagio Zampogna, Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Boris Eugeniev Sakakushev, Research Institute at Medical University of Plovdiv, Medical University of Plovdiv, Department of Surgical Propedeutics, Section of General Surgery, UMHAT St George Plovdiv, First Clinic of General Surgery, Bulgaria

Boyko Chavdarov Atanasov, Umhat Eurohospital, Medical university of Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Bruno Nardo, Annunziata Hospital, Unversity of Calabria, Italy

Bulent Calik, University of Healthy Sciences Izmir Bozyaka Education and Research Hospital, General Surgery Department, Turkey

Camilla Cremonini, Pisa university hospital, Italy

Carlos A. Ordoñez, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Fundacion Valle del Lili, Cali, Colombia

Charalampos Seretis, General University Hospital of Patras, Greece

Chiara Cascone, Fondazione Policlinico Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, Italy

Christos Chouliaras, 1st Department of Surgery, General Hospital of Nikaia, Piraeus, Greece

Cino Bendinelli, John Hunter Hospital. Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Claudia Lopes, Hospital Universitario Donostia-Osakidetza, Spain

Claudio Guerci, Ospedale Luigi Sacco, Italy

Clemens Weber, Department of Neurosurgery, Stavanger University Hospital, Norway

Constantinos Nastos, Attikon University Hospital, Greece

Cristian Mesina, Emergency County Hospital of Craiova, Romania

Damiano Caputo, Department of Surgery University Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Italy

Damien Massalou, Acute care surgery, University Hospital of Nice, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice, Nice, France

Davide Cavaliere, Department of Surgery, Forlì Hospital - AUSL della Romagna, Italy

Deborah A McNamara, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland

Demetrios Demetriades, USC School of Medicine, Los Angeles, United States

Desirè Pantalone, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine University of Florence, University Hospital Careggi, Florence, Italy

Diego Coletta, AO Ospedali Riuniti Marche Nord, Department of General Surgery, Italy

Diego Sasia, General and Oncological Surgery Unit, Santa Croce and Carle Hospital, Cuneo, Italy

Diego Visconti, Chirurgia Generals d´Urgenza e PS, AOU Cittá della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy

Dieter G. Weber, Department of General Surgery, Royal Perth Hospital & The University of Western Australia, Australia

Diletta Corallino, Department of General Surgery and Surgical Specialities „Paride Stefanini“, Sapienza, University of Rome, Italy

Dimitrios Chatzipetris, Department of Surgery, Metaxa Cancer Hospital, Piraeus, Greece

Dimitrios K. Manatakis, Department of Surgery, Athens Naval and Veterans Hospital, Athens, Greece

Dimitrios Ntourakis, School of Medicine, Division of Surgery, European University Cyprus, Greece

Dimitrios Papaconstantinou, Attikon University Hospital, 3rd Department of Surgery, Greece

Dimitrios Schizas, First Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Dimosthenis Chrysikos, First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, Hippocration Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Dmitry Mikhailovich Adamovich, Department of Surgical Diseases II, Gomel State Medical University, Gomel, Belarus

Doaa Elkafrawy, Kafersaad general hospital, Egypt

Dragos Serban, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Carol Davila Bucharest & 4th Surgery Department of University Emergency Hospital Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

Edgar Fernando Hernández García, Cirugía de trauma, Hospital Central Militar, Ciudad de México, Mexico

Edoardo Baldini, Ospedale Santa Maria delle Stelle, Melzo, Italy

Edoardo Picetti, Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Parma University Hospital, Parma, Italy

Edward C.T.H. Tan, Radboud university medical center, Department of Surgery, Netherlands

Efstratia Baili, Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Eftychios Lostoridis, Kavala General Hospital, Kavala, Greece

Elena Adelina Toma, Surgery Department, UMF Carol Davila Bucharest, Romania

Elif Colak, University of Samsun, Turkey

Elisabetta Cerutti, Department of Anesthesia and Transplant Surgical Intensive care, Ospedali Riuniti, Ancona, Italy

Elmin Steyn, Stellenbosch University and Tygerberg Hospital, South Africa

Elmuiz A. Hsabo, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Emmanouil Ioannis Kapetanakis, Department of Thoracic Surgery, “Attikon” University Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Emmanouil Kaouras, Department of Surgery, Metaxa Cancer Hospital, Piraeus, Greece

Emmanuel Schneck, Department of Anesthesiology, Operative Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Therapy, University Hospital of Giessen, Rudolf-Buchheim-Strasse 7, Giessen, Germany

Emrah Akin, Sakarya University Faculty of Medicine, Turkey

Emre Gonullu, General Surgery, Sakarya training and research hospital, Sakarya, Turkey

Enes çelik, Derik State Hospital, Turkey

Enrico Cicuttin, General, Emergency and Trauma Surgery, Pisa University Hospital, Pisa, Italy

Enrico Pinotti, Policlinico San Pietro, Italy

Erik Johnsson, Department of Surgery, Sahlgren University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Ernest E. Moore, Director of Research Ernest E Moore Shock Trauma Center at Denver Health, United States

Ervis Agastra, Regional Hospital of Korce, Albania

Evgeni Nikolaev Dimitrov, Department of Surgical Diseases, University Hospital "Prof. Dr. Stoyan Kirkovich" Stara Zagora, Bulgaria

Ewen A Griffiths, Department of Upper GI Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom

Fabrizio D'Acapito, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Italy

Federica Saraceno, UOC of General and Minimally Invasive Surgery, Hospital „San Paolo“, Largo Donatori del Sangue 1, Civitavecchia, Rome, Italy

Felipe Alconchel, Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital (IMIB-Arrixaca), Spain

Felix Alexander Zeppernick, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital of Giessen, Giessen, Germany

Fernando Machado Rodríguez, Departamento de Emergencia, Hospital de Clínicas „Dr. Manuel Quintela“ - Facutad de Medicina de la UdelaR, Montevideo, Uruguay

Fikri Abu-Zidan, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, UAE University, Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates

Francesca Pecchini, Division of General Surgery, Emergency and New Technologies, Ospedale Civile Baggiovara, AOU, Modena, Italy

Francesco Favi, UOC Chirurgia Generale e DÚrgenza Cesena Ausl della Romagna, Italy

Francesco Ferrara, Department of Surgery, San Carlo Borromeo Hospital, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan, Italy

Francesco Fleres, Department of Human Pathology of the Adult and Evolutive Age “Gaetano Barresi”, Section of General and Emergency Surgery, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

Francesco Pata, Department of Surgery, Nicola Giannettasio Hospital, Corigliano-Rossano, Italy

Francesco Pietro Maria Roscio, ASST Valle Olona Busto Arsizio, Italy

Francesk Mulita, Department of Surgery, General University Hospital of Patras, Greece

Frank J. M. F. Dor, 1. Imperial College Renal and Transplant Centre, Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, 2. Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom

Fredrik Linder, Department of Surgical Sciences, Emergency Surgery, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Gabriel Dimofte, Institutul Regional de Oncologie Iasi, Universitatea de Medicina si Farmacie „Grigore T. Popa“ Iasi, Romania

Gabriel Rodrigues, General Surgery, Kasturba Medical College Hospital, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India

Gabriela Nita, Sant'Anna Hospital, AUSL Reggio Emilia, Italy

Gabriele Sganga, Emergency Surgery & Trauma, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Roma, Italy

Gennaro Martines, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico Bari, Italy

Gennaro Mazzarella, Department of Emergency Surgery, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Gennaro Perrone, Department of emergency surgery, Parma Maggiore Hospital, Parma, Italy

George Velmahos, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Georgios D. Lianos, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Ioannina, Greece

Gia Tomadze, Surgery Department of Tbilisi State Medical University, Georgia

Gian Luca Baiocchi, UOC General Surgery, ASST Cremona; Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Italy

Giancarlo D'Ambrosio, Policlinico Umberto I, Univeristà La Sapienza, Roma, Italy

Gianluca Pellino, Department of Advanced Medical and Surgical Sciences, Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy

Gianmaria Casoni Pattacini, Division of General Surgery, Emergency and New Technologies, Ospedale Civile Baggiovara, AOU, Modena, Italy

Giorgio Giraudo, Department of Surgery ASO Santa Croce e Carle Cuneo, Italy

Giorgio Lisi, Department of Surgery, Sant'Eugenio Hospital, piazzale dell'umanesimo 10, Rome, Italy

Giovanni Domenico Tebala, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Giovanni Pirozzolo, Ospedale dell'Angelo - ULSS3 Serenissima – Venice, Italy

Giulia Montori, General surgery, Vittorio Veneto hospital (TV), Italy

Giulio Argenio, UOC Chirurgia Generale ed Oncologica, AO San Pio, Benevento, Italy

Giuseppe Brisinda, Department of Surgery, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A Gemelli IRCCS and Università Cattolica S. Cuore, Rome, Italy

Giuseppe Currò, AOU Mater Domini Catanzaro - Magna Graecia University of Catanzaro, Italy

Giuseppe Giuliani, Department of general and emergency surgery, Misericordia Hospital, Grosseto, Italy

Giuseppe Palomba, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Italy

Giuseppe Roscitano, University of Catania, Italy

Gökhan Avşar, Ankara university faculty of medicine department of surgical oncology, Turkey

Goran Augustin, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, Croatia

Guglielmo Clarizia, UOC Chirurgia Generale, PO Sondrio, ASST Valtellina e Alto Lario, Italy

Gustavo M. Machain Vega, University of Asuncion, Faculty of Medical Sciences, II Chair and Service of General Surgery Hospital de Clinicas FCM, Paraguay

Gustavo P. Fraga, Division of Trauma Surgery, University of Campinas (Unicamp), Brazil

Harsheet Sethi, Acute Surgical Unit, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Hazim Abdulnassir Eltyeb, General Surgery, Health Education North East, United Kingdom

Helmut A. Segovia Lohse, II Cátedra de Clínica Quirúrgica. Hospital de Clínicas. Universidad Nacional de Asunción. San Lorenzo, Paraguay

Herald René Segovia Lohse, II Cátedra de Clínica Quirúrgica, Hospital de Clínicas, Universidad Nacional de Asunción, San Lorenzo, Paraguay

Hüseyin Bayhan, Mardin Training and Research Hospital, Turkey

Hytham K. S. Hamid, Kuwaiti Specialized Hospital, Sudan

Igor A. Kryvoruchko, Kharkiv National Medical University, Ukraine

Immacolata Iannone, Azienda Ospedaliera Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Italy

Imtiaz Wani, Govt Gousia Hospital, Srinagar, India

Ioannis I. Lazaridis, Clarunis, Department of Visceral Surgery, University Centre for Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases, St. Clara Hospital and University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Ioannis Katsaros, Department of Surgery, Metaxa Cancer Hospital, Pireaus, Greece

Ioannis Nikolopoulos, Lewisham & Greenwich NHS Trust, United Kingdom

Ionut Negoi, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Bucharest, Emergency Hospital of Bucharest, Romania

Isabella Reccia, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Hammersmith Hospital, Imerpial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom

Isidoro Di Carlo, University of Catania, Italy

Iyiade Olatunde Olaoye, Surgery Department, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria

Jacek Czepiel, Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland

Jae Il Kim, Department of Surgery, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, South Korea

Jeremy Meyer, University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Jesus Manuel Saenz Terrazas, Senior Surgeon for the International Committee of the Red Cross, Nigeria

Joel Noutakdie Tochie, Anaesthesiologist and Intensive Care Physician, Laquintinie Hospital of Douala, Douala, Cameroon

Joseph M. Galante, University of California, Davis, United States

Justin Davies, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Kapil Sugand, Imperial College London, United Kingdom

Kebebe Bekele Gonfa, Maddawalabu University Goba Referral Hospital, Ethiopia

Kemal Rasa, Anadolu Medical Center Hospital affiliated with Johns Hopkins Hospital, Kocaeli, Turkey

Kenneth Y. Y. Kok, Pengiran Anak Puteri Rashidah Saadatul Bolkiah Institue of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei darussalam, Brunei

Konstantinos G. Apostolou, 1st Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laiko General Hospital, Athens, Greece

Konstantinos Lasithiotakis, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece

Konstantinos Tsekouras, Sismanogleio General Hospital, Athens, Greece

Kumar Angamuthu, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Infection Prevention & Control, Almana General Hospital, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

Lali Akhmeteli, Tbilisi State Medical University, Georgia

Larysa Sydorchuk, Bukovinian State Medical University, Ukraine

Laura Fortuna, General Surgery, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Careggi (AOUC), Largo Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla, Firenze (FI), Italy

Leandro Siragusa, Department of Surgery, Università degli studi di Roma Tor Vergata, Italy

Leonardo Pagani, Antimicrobial Stewardship Program, Infectious Diseases Branch, Bolzano Central Hospital, Italy

Leonardo Solaini, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Morgagni Pierantoni Hospital, Forlì, Italy

Lisa A. Miller, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, United States

Lovenish Bains, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India

Luca Ansaloni, San Matteo Hospital, Pavia, Italy

Luca Ferrario, General Surgery Trauma Team ASST-GOM Niguarda, Milan, Italy

Luigi Bonavina, Department of Biomedical Sciences for Health, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Division of General and Foregut Surgery, University of Milan, Italy

Luigi Conti, Acute care Surgery Unit , Department of Surgery, AUSL Piacenza, Italy

Luis Antonio Buonomo, Hospital Zonal de Agudos "Dr. Alberto Balestrini", Argentina

Luis Tallon-Aguilar, Virgen del Rocío University Hospital, Spain

Lukas Tomczyk, Department of general and visceral surgery, General Hospital Lich, Germany

Lukas Werner Widmer, Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, University Hospital of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Maciej Walędziak, Military Institute of Medicine, Department of General Surgery, Poland

Mahir Gachabayov, Vladimir City Emergency Hospital, Russia

Maloni Bulanauca, Department of Surgery, Labasa Hospital, Fiji

Manu L.N.G. Malbrain, Intensive Care Medicine, International Fluid Academy, Lovenjoel, Belgium and First Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, Medical University of Lubin, Poland

Marc Maegele, Department for Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery, Cologne-Merheim Medical Center (CMMC), Institute for Research in Operative Medicine (IFOM), University Witten-Herdecke (UW/H), Campus Cologne-Merheim, Ostmerheimerstr. 200, Cologne, Germany

Marco Catarci, Ospedale Sandro Pertini, Roma, Italy

Marco Ceresoli, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy

Maria Chiara Ranucci, Azienda ospedaliera Santa Maria di Terni, Italy

Maria Ioanna Antonopoulou, Naval and Veteran Hospital of Crete, Greece

Maria Papadoliopoulou, General University Hospital Attikon, Athens, Greece

Maria Rosaria Valenti, Policlinico di Catania, Italy

Maria Sotiropoulou, Evaggelismos General Hospital, Greece

Mario D'Oria, Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Cardiovascular Department, University Hospital of Trieste ASUGI, Italy

Mario Serradilla Martín, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Aragón, Department of Surgery, Miguel Servet University Hospital, Zaragoza, Spain

Markus Hirschburger, Department of General, Visceral and Thoracic Surgery, Hospital of Worms, Worms, Germany

Massimiliano Veroux, General Surgery, University Hospital of Catania, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies, University of Catania, Italy

Massimo Fantoni, Fondazione Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS - UNiversità Cattolica S. Cuore, Italy

Matteo Nardi, San Camillo Forlanini Hospital, Italy

Matti Tolonen, HUS Abdominal Center, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Finland

Mauro Montuori, Policlinico San Pietro - Department of Surgery - Via Carlo Forlanini 15 Ponte San Pietro, Italy

Mauro Podda, Department of Surgical Science, University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy

Maximilian Scheiterle, SOD Chirurgia d'Urgenza, Careggi, Italy

Maximos Frountzas, First Propaedeutic Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Medical School, Hippocration General Hospital of Athens, Greece

Mehmet Sarıkaya, Mardin, Turkey

Mehmet Yildirim, University of Health Sciences İzmir Bozyaka Training and Research Hospital General Surgery Department, Turkey

Michael Bender, Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital of Giessen, Germany

Michail Vailas, Laiko General hospital Athens, Greece

Michel Teuben, Cantonal Hospital Frauenfeld, Switzerland

Michela Campanelli, Emergency Surgery Unit, University Hospital of Tor Vergata, viale Oxford 81, Rome, Italy

Michele Ammendola, Health of Science Department, "Magna Graecia" University Medical School, Digestive Surgery Unit, "Mater Domini" Hospital, Catanzaro, Italy

Michele Malerba, Surgical Department ASL2 Savonese, Santa Corona Hospital, Pietra Ligure (SV), Italy

Michele Pisano, ASST Papa Giovanni Bergamo, Italy

Mihaela Pertea, Sf Spiridon Emegency Hospital Iasi, University of Medicine and Pharmacy "Grigore T Popa"Iasi, Romania

Mihail Slavchev, University Hospital Eurohospital, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Mika Ukkonen, Tampere University Hospital, Finland

Miklosh Bala, Department of General Surgery, Hadassah Medical Center and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Mircea Chirica, Service de chirurgie digestive, Centre hospitalier universitaire Grenoble Alpes, France

Mirko Barone, Department of Surgery, SS. Annunziata University Hospital of Chieti, Italy

Mohamed Maher Shaat, King Faisal Medical Complex in Taif, Saudi Arabia

Mohammed Jibreel Suliman Mohammed, Wirral University Teaching Hospital, United Kingdom

Mona Awad Akasha Abuelgasim, Kingston Hospital NHS foundation trust, United Kingdom

Monika Gureh, General surgery, AIIMS Bhuvneshwar, Bhuvneshwar, India

Mouaqit Ouadii, Hassan II hospital, Morocco

Mujdat Balkan, General Surgery, TOBB ETÜ Medical school, Ankara, Turkey

Mumin Mohamed, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, United Kingdom

Musluh Hakseven, Ankara University School of Medicine Department of General Surgery, Surgical Oncology, Turkey

Natalia Velenciuc, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Grigore T. Popa Iasi/ Regional Institute of Oncology Iasi, Romania

Nicola Cillara, Chirurgia Generale PO Santissima Trinità Cagliari, Italy

Nicola de'Angelis, Henri Mondor University Hospital (AP-HP), Faculty of Medicine, University of Paris Est, UPEC, France

Nicolò Tamini, ASST MONZA - Ospedale San Gerardo, Italy

Nikolaos J. Zavras, Department of Pediatric Surgery-General University Hospital "ATTIKON", Greece

Nikolaos Machairas, General Hospital of Athens “Laiko”, Greece

Nikolaos Michalopoulos, General University Hospital Attikon, Athens, Greece

Nikolaos N. Koliakos, Univerisity Hospital Attikon, Athens, Greece

Nikolaos Pararas, Dr Sulaiman Al Habib Hospital, Saudi Arabia

Noel E. Donlon, Trinity college Dublin st James hospital, Ireland

Noushif Medappil, Aster Malabar Institute of Medical Sciences (Aster MIMS - Calicut), India

Offir Ben-Ishay, Surgical Oncology, Division of Surgery, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel

Stefano Olmi, General and Oncological Surgery Department, Senior Research Vita-Salute, San Raffaele University, Milan, San Marco Hospital GSD, Zingonia (BG), Italy

Omar Islam, Wirral university teaching hospital, United Kingdom

Ömer Tammo, Mardin training and research hospital, Turkey

Orestis Ioannidis, 4th Department of Surgery, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, General Hospital “George Papanikolaou”, Thessaloniki, Greece

Oscar Aparicio, Parc Tauli Hospital Universitari Sabadell, Spain

Oussama Baraket, Deprtement of surghery bizerte hospital, Faculty of medicine of Tunis, Tunisia

Pankaj Kumar, Department of General Surgery, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Pasquale Cianci, Lorenzo Bonomo Hospital Andria-ASL BAT-University of Foggia, Italy

Per Örtenwall, Department of surgery, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Petar Angelov Uchikov, Medical university of Plovdiv, Department of special surgery, Medical faculty, University hospital “St. George”, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Philip de Reuver, Department of Surgery, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Philip F. Stahel, Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine, United States

Philip S. Barie, Department of Surgery, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Micaela Piccoli, Division of General Surgery, Emergency and New Technologies, Ospedale Civile Baggiovara, AOU, Modena, Italy

Piotr Major, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Poland

Pradeep H. Navsaria, Trauma Centre, Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

Prakash Kumar Sasmal, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, India

Raul Coimbra, Riverside University Health System MEdical Center / Loma Linda University, United States

Razrim Rahim, Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, Malaysia

Recayi Çapoğlu, General Surgery, Sakarya training and research hospital, Sakarya, Turkey

Renol M. Koshy, Luton & Dunstable University Hospital, United Kingdom

Ricardo Alessandro Teixeira Gonsaga, Centro Universitário Padre Albino, Catanduva (SP), Brazil

Riccardo Pertile, Department of Clinical and Evaluative Epidemiology, Health Service of Trento, Italy

Rifat Ramadan Mussa Mohamed, University Hospital Ayr, United Kingdom

Rıza Deryol, Department of General Surgery, Surgical Oncology Unit, Ankara University, School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

Robert G. Sawyer, Western Michigan University School of Medicine, United States

Roberta Angelico, HPB and Transplant Unit, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Roberta Ragozzino, General surgery and Trauma Team, ASST Niguarda, Milano, Piazza Ospedale Maggiore 3, Milan, Italy

Roberto Bini, ASST Niguarda Hospital, Italy

Roberto Cammarata, Campus Biomedico University of Rome, Italy

Rosa Scaramuzzo, General Surgery Unit, San Paolo Hospital, Rome, Italy

Rossella Gioco, General Surgery, Policlinico G. Rodolico Catania, Italy

Ruslan Sydorchuk, General Surgery Department, Regional Emergency Hospital Chernivtsi, Ukraine

Salma Ahmed, Wirral University Teaching Hospital, United Kingdom

Salomone Di Saverio, Ospedale Madonna del Soccorso San benedetto del Tronto, Italy

Sameh Hany Emile, Mansoura University Hospital, Egypt

Samir Delibegovic, Department of Surgery, University Clinical Center Tuzla, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Sanjay Marwah, Pt BDS Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India

Savvas Symeonidis, General Hospital of Thessaloniki Georgios Papanikolaou, Greece

Scott G. Thomas, Trauma Services, Indiana University School of Medicine, Beacon Health System, Memorial Hospital South Bend, Indiana, United States

Sebahattin Demir, Turkey

Selmy S. Awad, Mansoura university hospitals, Mansoura University, Egypt

Semra Demirli Atici, University of Health Sciences Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, Turkey

Serge Chooklin, Lviv National Medical University, Ukraine

Serhat Meric, General surgery department, Bağcılar training and research hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

Sevcan Sarıkaya, Mardin Training and Research Hospital, Mardin, Turkey

Sharfuddin Chowdhury, King Saud Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Shaza Faycal Mirghani, Sandwell General Hospital, United Kingdom

Sherry M. Wren, Stanford University, United States

Simone Gargarella, University “G.D’Annunzio” Chieti – Pescara, Italy

Simone Rossi Del Monte, ASL Roma 1 - Ospedale San Filippo Neri, Italy

Sofia Esposito, General, emergency and new technology surgery Unit, Baggiovara General Hospital, Modena, Italy

Sofia Xenaki, Department of General Surgery, University Hospital of Heraklion Crete, Greece

Soliman Fayez Ghedan Mohamed, KFMC, Saudi Arabia

Solomon Gurmu Beka, Emergency Surgery, Professional Specialist at Ethiopian Air Force Hospital, President of Ethiopian Emergency Surgery Association, Bishoftu, Oromia, Ethiopia

Sorinel Lunca, University of Medecine "Gr.T.Popa" Iasi Second Oncology Surgery Clinic Regional Institute of Oncology Iasi, Romania

Spiros G. Delis, University of Athens, Greece

Spyridon Dritsas, Colorectal and Peritoneal Oncology Centre, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom

Stefan Morarasu, 2nd Department of Surgical Oncology, Regional Institute of Oncology, Iasi, Romania

Stefano Magnone, ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII Bergamo, Italy

Stefano Rossi, Emergency surgery San Filippo Neri hospital ASL Roma1, Italy

Stefanos Bitsianis, 4th Department of Surgery of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Stylianos Kykalos, 2nd Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, General Hospital Laiko, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Suman Baral, Dirghayu Pokhara Hospital, Pokhara, Nepal

Sumita A Jain, SMS MEedical College and Hospital Jaipur, India

Syed Muhammad Ali, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Tadeja Pintar, Surgery Department, UMC Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Sloviena

Tania Triantafyllou, Advanced Upper GI Surgical Fellow, Athens, Greece

Tarik Delko, University Center for Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases, Basel, Switzerland

Teresa Perra, Università degli Studi di Sassari, Italy

Theodoros A. Sidiropoulos, Surgical Resident, 4th Surgical Department, Attikon University Hospital, Athens, Greece

Thomas M. Scalea, R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, United States

Tim Oliver Vilz, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Bonn, Venusberg Campus 1, Bonn, Germany

Timothy Craig Hardcastle, IALCH, Durban and University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Tongporn Wannatoop, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj hospital, Mahidol university, Bankok, Thailand

Torsten Herzog, Department of Surgery, St. Josef Hospital, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany

Tushar Subhadarshan Mishra, Department of Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Ugo Boggi, Division of General and Transplant Surgery, University of Pisa, Italy

Valentin Calu, Elias Emergency University Hospital, Romania

Valentina Tomajer, Ospedale San Raffaele Milan, Italy

Vanni Agnoletti, Azienda USL della Romagna – Cesena, Italy

Varut Lohsiriwat, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Victor Kong, Department of Surgery, University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa

Virginia Durán Muñoz-Cruzado, Virgen del Rocío University Hospital, Spain

Vishal G. Shelat, Department of General Surgery, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

Vladimir Khokha, Department of surgery, Mozyr city hospital, Belarus

Wagih Mommtaz Ghannam, Mansoura Faculty of Medicine, Egypt

Walter L. Biffl, Scripps Clinic Medical Group, United States

Wietse Zuidema, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Yasin Kara, Health Sciences University Kanuni Sultan Süleyman Training and Research Hospital General Surgery Clinic, Turkey

Yoshiro Kobe, Chiba Emergency Medical Center, Japan

Zaza Demetrashvili, Surgery Department, Tbilisi State Medical University, Georgia

Ziad A. Memish, Research and Innovation Center, King Saud Medical City, Ministry of Health & College of Medicine Alfaisal University, Saudi Arabia

Zoilo Madrazo, Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain

Zsolt J. Balogh, Department of Traumatology, John Hunter Hospital and University of Newcastle, Australia

Zulfu Bayhan, Sakarya University, Faculty of Medicine Department of General Surgery, Turkey

Martin Reichert, Massimo Sartelli, Markus A. Weigand, Matthias Hecker, Ingolf H. Askevold, Juliane Liese, Winfried Padberg and Andreas Hecker: core investigator.

Federico Coccolini and Fausto Catena: WSES project steering committee representative.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Each author had made substantial contributions to the present manuscript. MR, MS, MAW, MH, IHA, JL, WP, FCo, FCa and AH contributed to conception and design. MR, PUO, JN and AH were involved in acquisition and analysis of data. MR and AH interpreted data. MR, MH and AH contributed to writing first draft. MS, MAW, JL, WP, FCo and FCa were involved in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read the final version of the manuscript and gave final approval for the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: the author name misspelled as Dragos Seban under The WSES COVID-19 emergency surgery survey collaboration group the correct name is Dragos Serban.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Reichert, M., Sartelli, M., Weigand, M.A. et al. Two years later: Is the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic still having an impact on emergency surgery? An international cross-sectional survey among WSES members. World J Emerg Surg 17, 34 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00424-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00424-0