Abstract

Background

The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the effect of REBOA, compared to resuscitative thoracotomy, on mortality and among non-compressible torso hemorrhage trauma patients.

Methods

Relevant articles were identified by a literature search in MEDLINE and EMBASE. We included studies involving trauma patients suffering non-compressible torso hemorrhage. Studies were eligible if they evaluated REBOA and compared it to resuscitative thoracotomy. Two investigators independently assessed articles for inclusion and exclusion criteria and selected studies for final analysis. We conducted meta-analysis using random effect models.

Results

We included three studies in our systematic review. These studies included a total of 1276 patients. An initial analysis found that although lower in REBOA-treated patients, the odds of mortality did not differ between the compared groups (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.17–1.03). Sensitivity analysis showed that the risk of mortality was significantly lower among patients who underwent REBOA, compared to those who underwent resuscitative thoracotomy (RT) (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.68–0.97).

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis, mainly from observational data, suggests a positive effect of REBOA on mortality among non-compressible torso hemorrhage patients. However, these results deserve further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is a procedure that involves placement of an endovascular balloon in the aorta to obtain proximal control of hemorrhage [1]. In recent years, REBOA has become increasingly popular amongst trauma surgeons [2] for the management of traumatic non-compressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH) [3,4,5]. Although the use of REBOA in the trauma setting has been studied, most of the information comes from series of patients with blunt or penetrating trauma [6] and clear evidence on its effectiveness for improving mortality rates is lacking. Furthermore, little is known about the comparative effectiveness of REBOA and resuscitative thoracotomy (RT) on mortality in NCTH trauma patients.

The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the effect of REBOA, compared to RT, on mortality among NCTH trauma patients.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following Cochrane recommendations [7] and PRISMA guidelines [8].

Our PICO strategy was as follows: Patients: patients with non-compressible torso hemorrhage, intervention: REBOA, comparison: resuscitative thoracotomy, and outcomes: mortality and REBOA deployment complications. For this strategy, the proposed systematic review will answer the following questions:

-

1.

In patients with non-compressible torso hemorrhage, does REBOA in comparison with RT result in reduced mortality?

-

2.

What is the type and frequency of complications related to REBOA deployment in included studies?

Inclusion criteria

We included studies involving patients that suffered blunt or penetrating injuries to the torso. Studies were eligible if they assessed the effect of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) on relevant outcomes among NCTH patients and compared it to traditional open aortic occlusion by resuscitative thoracotomy. Studies without comparison group were excluded.

Outcomes

Mortality and complications related to REBOA deployment were the outcomes of interest. Only those studies with sufficient information on the outcomes (effect size and associated precision) were included in the meta-analysis.

Search methods

We built a highly sensitive search strategy (search strategies are available in Additional file 1) following established recommendations [9, 10]. The literature search was performed in MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to May 2017 using and combining terms and synonyms related to our condition of interest (trauma, injuries, non-compressible torso hemorrhage, etc.) and our intervention of interest (resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta). We also searched key journals (Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, World Journal of Emergency Surgery, European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery and the Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Surgery). Finally, references from previous relevant narrative and systematic reviews were examined.

Study selection and data collection

Two individuals independently examined the titles and abstracts identified in the searches. Articles that appeared relevant were selected for full-text review. Two researchers independently reviewed full-text articles for final eligibility. A third reviewer, an experienced trauma surgeon of our review team, resolved disagreements in both phases. The following information was independently extracted using a standardized data form: author, year of publication, the region of origin, trauma characteristics, patient demographics and clinical characteristics, type of operative interventions performed, number and type of complications, mortality, and measures of association for mortality reported.

Risk of bias

The internal validity of each non-randomized study included in this systematic review was critically evaluated for bias according to the Methodological Index for Non-randomized studies (MINORS) [11]. MINORS evaluate 12 methodological items by scoring each one as 0 (red) if not reported (high risk of bias); 1 (yellow), reported but inadequate (unclear risk of bias); and 2 (green), reported and adequate (low risk of bias). Moreover, we evaluated three additional domains through which bias can be introduced in a study and that are important in trauma outcomes research. Those were as follows: the risk of indication bias, the risk of survival bias, and the risk of reporting bias (selective reporting) [7, 12]. Two independent investigators made the evaluation of the risk of bias as previously mentioned and computed a graphic representation of potential bias in a visual table where high, unclear, and low risks of bias were represented by the colors red, yellow, and green, respectively.

Data analysis

A meta-analysis was performed to assess the effect of REBOA on mortality, compared it to open aortic cross-clamping by resuscitative thoracotomy. The meta-analysis was restricted to available measures of associations with their correspondent confidence intervals (CIs).

Unadjusted ORs and their CIs were calculated in a 2 × 2 table using data provided in studies. Adjusted ORs and CIs were extracted as provided. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios were pooled using a random-effects (DerSimonian and Laird) meta-analysis. The results were reported in forest plots of the estimated effects of the included studies with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I 2 test, which corresponded to low (I 2 < 25%), medium (I 2 = 25–75%), and high (I 2 > 75%) heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

The risk ratio is thought to be a better measure of effect to communicate research findings [13]. Moreover, the odds ratio may overestimate a risk association or a treatment effect when the outcome of interest is common in the study population [14, 15]. In this case, our outcome of interest was mortality, which is a very common outcome in patients suffering severe torso trauma and NCTH. Therefore, we decided to convert adjusted odds ratios (ORs) extracted from the studies to risk ratios (RRs) using an inverse probability weighted binomial model [16]. The model used the following equation to convert an OR to an RR:

In this equation, q is the incidence of the outcome of interest in the unexposed (control group). For this analysis, the unexposed were those groups who underwent open aortic cross-clamping by resuscitative thoracotomy. The transformed measures of effect were pooled using a random effect model.

All analyses were done in Stata statistical software.

Results

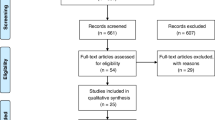

We identified 1084 records from our searches, of which 13 studies were eligible to be included in our systematic review. These articles were retrieved as full texts and reviewed. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, three studies were included in the systematic review, all of them in both the qualitative and quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis). Figure 1 shows the flowchart for the selection of the studies.

Characteristics of included studies

Included studies were published in 2016 [17, 18] and 2017 [19]. These studies included a total of 1276 patients. Two were retrospective cohort studies [17, 19] and one was a prospective cohort [18].

Characteristics of participants

A total of 1276 participants were analyzed in the included studies. Overall, REBOA was deployed in 873 (68%) patients while open aortic cross-clamping by resuscitative thoracotomy was performed in 403 (32%).

An overview of patients’ characteristics by interventions is presented in Table 1. The majority was male (n = 851/1276), and all were victims of torso trauma by blunt or penetrating mechanisms. Age structure was heterogeneous and included both young and elderly patients. Two studies reported information on injury severity. In these studies, patients suffered severe trauma and presented primarily with moderate (AIS = 2) and/or serious (AIS = 3) injuries.

Data on operative interventions was captured. Overall, 494 (38%) and 271 (21%) patients underwent exploratory laparotomy and arterial embolization, respectively. Two studies reported data on splenic and hepatic procedures; these included different damage control strategies such as packing and resections. The same studies reported information on operative interventions for pelvic fractures management, which included the use of packing, external fixation, and surgery.

Differences between REBOA and resuscitative thoracotomy patients

Two studies reported data on initial blood pressure and injury severity. In these studies, RT patients were more likely to present with significantly lower values systolic blood pressure (SBP: median (IQR): DuBose: REBOA = 23 (105) vs. RT = 0 (80), p = 0.01; Abe: REBOA = 89 (46) vs. RT = 87 (45), p < 0.001). However, REBOA and RT patients were similar in severity of injuries as reflected by reported AIS and ISS. One study reported the probability of survival for both groups. This study showed that patients that underwent REBOA had a significantly higher probability of survival on admission (TRISS (probability of survival), mean (SD): Abe: REBOA = 0.43 (0.36) vs. RT = 0.27 (0.30), p < 0.001].

Resuscitation strategies, including transfusions requirements, were reported in all studies. Two studies reported transfusions requirements as a continuous variable. In these studies, no significant differences were found regarding the amounts of transfusions in first 24 h. The study by Abe et al. reported the number of patients that required transfusions. They found that a significantly higher proportion of patients required transfusions in the REBOA group (Abe: required transfusion, n (%): REBOA = 542/636 (85%) vs. RT = 197/267 (74%), p < 0.001].

Among operative interventions, overall, REBOA patients underwent arterial embolization more often than RT patients (arterial embolization, n (%): REBOA = 232/873 (26%) vs. RT = 39/403 (9.6%), p < 0.01). Finally, mortality was significantly higher in patients that underwent RT (mortality, n (%): REBOA = 528/873 (60.4%) vs. RT = 315/403 (78.1%), p < 0.01].

Risk of bias

A summary of the risk of bias is presented in Fig. 2 (a detailed description on how studies were evaluated is available in Additional file 1). Studies were prone to biases present in retrospective studies. However, included studies were rated as having high risk of indication and survival bias. The study by Aso [19] had a high risk of selective reporting.

Outcomes

Mortality

Our primary outcome was mortality. All studies reported information on this outcome. Data captured included the proportion of deaths in each group and the adjusted measures of association for in-hospital mortality. Table 1 provides an overview of the primary outcome information extracted from each study.

REBOA-related complications

Only the study by DuBose et al. [18] reported complications related to REBOA deployment. In this study, three patients of those in the REBOA group (n = 46) suffered complications, which included one pseudoaneurysm and two cases of distal arterial embolism.

Quantitative synthesis results

Meta-Analysis of unadjusted odds ratios showed that the odds of mortality were lower in patients that underwent REBOA compared to those that were taken to RT (OR 0.45; 95% CI 0.34–0.61) (Fig. 3).

To be able to pool the adjusted odds ratios in a meta-analysis, the hazard ratio reported in the study by Aso [19] was converted to an odds ratio. For the procedure, we assumed that the hazard ratio is a type of relative risk and, thus, is asymptotically similar to a relative risk [14]. Then, using the inverse probability weighted binomial model (10) we transformed the adjusted hazard ratio of mortality reported in the study by Aso [19] to an odds ratio. Following this approach, we obtained an adjusted odds ratio of mortality (Aso: OR 0.821; 95% CI 0.306–1.234). After combining adjusted odds ratios using a random effect model, we found that, although lower in REBOA patients, the odds of mortality did not significantly differ between compared groups (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.17–1.03) (Fig. 4).

Sensitivity analyses

When the outcome of interest (mortality) is common, the OR can jeopardize a risk association or a treatment effect by producing biased estimates of the underlying risk ratio (7)(8). In this systematic review, mortality was high in all groups (RT, REBOA) with rates ranging from 47 to 90% (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, we decided to convert reported ORs to RRs as proposed in the “Methods” section.

Using the inverse probability weighted binomial model, we obtained the transformed risk ratios of in-hospital mortality for the studies by Abe [17] (RR 0.796; 95% CI 0.624–0.924) and DuBose [18] (RR 0.687; 95% CI 0.217–1.06). For the hazard ratio reported by Aso, we assumed the asymptotical similarity between the hazard ratio and the risk ratio and combined it with the transformed risk ratios using a random effect model. This analysis showed that the risk of mortality was significantly lower among torso trauma patients who underwent REBOA, compared to those who underwent RT (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.68–0.97) (Fig. 5).

Further sensitivity analyses were performed by methods of adjustment used in individual studies. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of risk ratios from the studies where a propensity score method was used (Aso, Abe) [17, 19]. In this analysis, the risk of mortality was significantly lower in patients who underwent REBOA, compared to those who underwent RT (RR 0.818; 95% CI 0.683–0.979; I 2 = 0.0%).

A final sensitivity analysis that took into account the evaluation of risk of bias was performed. We ranked the study by Aso [19] with a high risk of selective reporting. They did not report important baseline trauma characteristics such as those related to initial vital signs, physiological status, and injury severity. Not reporting these variables and, furthermore, not including them in the multivariate model analysis could have introduced further indication bias. Therefore, we decided to exclude the study by Aso [19] and to run a random effect model of the remaining studies. This analysis found that the risk of death was significantly lower among REBOA patients (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.653–0.956; I 2 = 0.0%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the comparative effectiveness of REBOA and resuscitative thoracotomy on mortality among trauma patients suffering NCTH. Our initial analysis found that although lower in REBOA patients, the odds of mortality did not significantly differ between the compared groups. Although sensitivity analyses showed consistent results on the positive effect of REBOA on mortality, results could be comprised by the presence of survival and indication bias within individual studies.

Non-compressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH) is a life-threatening condition defined as shock associated with hemorrhage due to vascular disruption secondary to pulmonary or solid organ injury, major vascular trauma or pelvic fracture [20]. Concerning this, patients included were primarily victims of serious and severe injuries as reflected by the abbreviated injury scale scores and the procedures for hemorrhage control reported. The need for hemostatic procedures is a fundamental component in the definition of NCTH. These comprise mainly open surgery and endovascular interventional procedures. We found that patients included underwent different aggressive surgical and endovascular procedures for immediate hemorrhage control. Therefore, patients analyzed in this systematic review can be classified as suffering wounds that ultimately ended in a pattern of injury consistent with NCTH anatomic definition.

Shock secondary to NCTH is associated with higher mortality rates. However, a proportion of NCTH-related deaths are potentially preventable [20, 21]. Therefore, research on new technologies such as REBOA for further progress in the principles of damage control resuscitation is of paramount importance for improving survival among NCTH patients. Although we found that the risk of death was lower in NCTH REBOA-treated patients, other reports have shown an increased mortality with the use of REBOA in this population. For example, Norii et al. [22] and Inoue et al. [23] showed that among similarly ill trauma patients, the use of REBOA was associated with higher odds of mortality compared to patients who did not receive REBOA.

In this systematic review, REBOA-treated patients underwent endovascular angioembolization more often than RT patients (Arterial embolization, n (%): REBOA = 232/873 (26%) vs. RT = 39/403 (9.6%), p < 0.01). This result further supports the concept that in patients suffering torso trauma in which NTCH is suspected, early REBOA deployment could aid in hemodynamic stabilization while hemorrhage control is achieved by endovascular procedures. To date, one study reported the use of REBOA followed by arterial embolization [24]. In this study, seven patients with severe hepatic and splenic blunt injuries were managed following damage control resuscitation strategies which included early massive transfusion followed by REBOA deployment for hemodynamic support and angioembolization for definitive hemorrhage control. Six of seven patients survived demonstrating the feasibility of REBOA in these scenarios.

Although our quantitative synthesis shows that REBOA is associated with lower mortality, these results could be flawed by the presence of indication and survival bias within individual studies [12]. Indication bias arises when patients are classified on the basis of the non-randomized intervention they received during the natural course of their medical treatment. Survival bias appears when comparing groups in which patients may die before treatment is initiated [12]. As shown in Table 1, patients that underwent RT were more likely to present with cardiac arrest and lower values of systolic blood pressure. Furthermore, the study by Abe [17] reported that REBOA patients had a significantly higher probability of survival on arrival. These facts could increase the risk of significant indication and survival bias, which are selection biases and are a primary evil in observational studies of non-randomized interventions. The main trouble with these biases is that their presence may produce biased effect estimates, thus comprising validity of results.

Traditionally, RT has been used in severely ill trauma patients as the last effort for resuscitation of the moribund patient [25]. REBOA is thought to emulate RT with the advantage of being a less invasive procedure. However, the fact that RT was performed in patients with a higher physiological exhaustion and with a lower probability of survival illustrates a lack of concrete indications for REBOA use in trauma patients. Moreover, it poses the question if REBOA is a comparable intervention to RT or if it is an intervention aimed to prevent hemodynamic collapse in non-agonal unstable patients.

Knowing the balance of benefits and harms of interventions is a paramount component of evidence-based health care. Therefore, we acknowledge that only the study by DuBose et al. [18] reported complications related to REBOA deployment and that was one main reason to rate the studies by Aso [19] and Abe [17] as having a high and unclear risk of selective reporting respectively. Although the severity and proportion of complications related to REBOA deployment were low in the DuBose series, another report by Saito et al. [26] documented serious adverse events that ultimately ended in lower limb amputations in 2 of 14 patients. However, REBOA is an evolving endovascular technology, and new strategies such as improvements in endovascular skills training [27, 28] and the advent of smaller diameter catheters [29] may improve the safety related to its deployment [30].

Although we found a benefit of REBOA over RT in NCTH patients, our results can be comprised by the biases present in primary studies. Future studies must address specific indications for REBOA to know which population could benefit from its use. Furthermore, trauma researchers should determine if REBOA is a comparable intervention to RT. Therefore, prospective evaluation with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria that ameliorates noise and biased results should be undertaken.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis mainly from observational data suggests that the use of REBOA is associated with lower mortality. However, our findings deserve further investigation.

References

Stannard A, Eliason JL, Rasmussen TE. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) as an adjunct for hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg [Internet]. 2011;71:1869–72. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2011/12000/Resuscitative_Endovascular_Balloon_Occlusion_of.62.aspx.

Belenkiy SM, Batchinsky AI, Rasmussen TE, Cancio LC. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control: Past, present, and future. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. [Internet]. 2015;79: S236–S242. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2015/10001/Resuscitative_endovascular_balloon_occlusion_of.29.aspx.

Gupta BK, KHANEJA SC, FLORES L, EASTLICK L, LONGMORE W, Shaftan GW. The role of intra-aortic balloon occlusion in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg [Internet]. 1989;29:861–5. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/1989/06000/The_Role_of_Intra_aortic_Balloon_Occlusion_in.26.aspx.

Moore LJ, Brenner M, Kozar RA, Pasley J, Wade CE, Baraniuk MS, et al. Implementation of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta as an alternative to resuscitative thoracotomy for noncompressible truncal hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;79:523–32.

Morrison JJ, Galgon RE, Jansen JO, Cannon JW, Rasmussen TE, Eliason JL, et al. A systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;80:324–34.

Brenner ML, Moore LJ, DuBose JJ, Tyson GH, McNutt MK, Albarado RP, et al. A clinical series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control and resuscitation. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. [Internet]. 2013;75:506–511. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2013/09000/A_clinical_series_of_resuscitative_endovascular.24.aspx.

Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. Cochrane Handb. Syst. Rev. Interv. Cochrane B. Ser. John Wiley and Sons; 2008.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med [Internet]. 2009;6:e1000100. Public Library of Science. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Robinson KA. Development of a highly sensitive search strategy for the retrieval of reports of controlled trials using PubMed. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:150–3.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-6.

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–6. Blackwell Science Pty.

del Junco DJ, Fox EE, Camp EA, Rahbar MH, Holcomb JB. Seven deadly sins in trauma outcomes research: an epidemiologic post-mortem for major causes of bias. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:S97–103.

Grant RL. Converting an odds ratio to a range of plausible relative risks for better communication of research findings. BMJ Br Med J. 2014;348: f7450.

Nurminen M. To use or not to use the odds ratio in epidemiologic analyses? Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;11:365–71.

Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1.

Popham F. Converting between marginal effect measures from binomial models. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:590–1.

Abe T, Uchida M, Nagata I, Saitoh D, Tamiya N. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta versus aortic cross clamping among patients with critical trauma: a nationwide cohort study in Japan. Crit Care. 2016;20:400.

DuBose JJ, Scalea TM, Brenner M, Skiada D, Inaba K, Cannon J, et al. The AAST prospective Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) registry: data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg [Internet]. 2016;81:409–19. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2016/09000/The_AAST_prospective_Aortic_Occlusion_for.1.aspx.

Aso S, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta or resuscitative thoracotomy with aortic clamping for noncompressible torso hemorrhage: A retrospective nationwide study. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(5):910-914.

Kisat M, Morrison JJ, Hashmi ZG, Efron DT, Rasmussen TE, Haider AH. Epidemiology and outcomes of non-compressible torso hemorrhage. J Surg Res. 2013;184:414–21.

Kauvar DS, Wade CE. The epidemiology and modern management of traumatic hemorrhage: US and international perspectives. Crit Care. 2005;9:S1.

Norii T, Crandall C, Terasaka Y. Survival of severe blunt trauma patients treated with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta compared with propensity score-adjusted untreated patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(4):721-8.

Inoue J, Atsushi S, Ayako Y, Koichi H, Hiroki M, Yasuhiro O. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aortamight be dangerous in patients with severe torso trauma: a propensity score analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:559–67.

Ogura T, Lefor AT, Nakano M, Izawa Y, Morita H. Nonoperative management of hemodynamically unstable abdominal trauma patients with angioembolization and resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:132–5.

Moore EE, Knudson MM, Burlew CC, Inaba K, Dicker RA, Biffl WL, et al. Defining the Limits of Resuscitative Emergency Department Thoracotomy: A Contemporary Western Trauma Association Perspective. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2011;70(2):334-9.

Saito N, Matsumoto H, Yagi T, Hara Y, Hayashida K, Motomura T, et al. Evaluation of the safety and feasibility of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:897–904.

Villamaria CY, Eliason JL, Napolitano LM, Stansfield RB, Spencer JR, Rasmussen TE. Endovascular skills for trauma and resuscitative surgery (ESTARS) course: curriculum development, content validation, and program assessment. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:929–35. discussion 935–6.

Brenner M, Hoehn M, Pasley J, Dubose J, Stein D, Scalea T. Basic endovascular skills for trauma course: bridging the gap between endovascular techniques and the acute care surgeon. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:286–91.

Teeter WA, Matsumoto J, Idoguchi K, Kon Y, Orita T, Funabiki T, et al. Smaller introducer sheaths for REBOA may be associated with fewer complications. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:1.

Taylor JR, Harvin JA, Martin C, Holcomb JB, Moore LJ. Vascular complications from resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):S120-S123.

Acknowledgements

Dedicated to the memory of Isabel C. Muñoz Chavez MD.

Funding

No funding. This article received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data is a property of the authors and could be available by request at ramiro.manzano@correounivalle.edu.co.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RMN, MPN, EF, PF, ER, HAG, PB, JPH, AFG, and CAO contributed equally to this work. RMN and CAO designed the research. RMN, MPN, EF, PF, ER, HAG, PB, JPH, AFG, and CAO performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Manzano Nunez, R., Naranjo, M.P., Foianini, E. et al. A meta-analysis of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) or open aortic cross-clamping by resuscitative thoracotomy in non-compressible torso hemorrhage patients. World J Emerg Surg 12, 30 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-017-0142-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-017-0142-5