Abstract

Background

Radiotherapy dose and target volume prescriptions for anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC) vary considerably in daily practice and guidelines, including those from NCCN, UK, Australasian, and ESMO. We conducted a pattern-of-care survey to assess the patient management in German speaking countries.

Methods

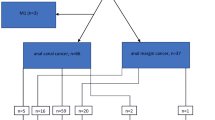

We developed an anonymous questionnaire comprising 18 questions on diagnosis and treatment of ASCC. The survey was sent to 361 DEGRO-associated institutions, including 41 university hospitals, 118 non-university institutions, and 202 private practices.

Results

We received a total of 101 (28%) surveys, including 20 (19.8%) from university, 36 (35.6%) from non-university clinics, and 45 (44.6%) from private practices. A total of 28 (27.8%) institutions reported to treat more than 5 patients with early-stage ASCC and 42 (41.6%) institutions treat more than 5 patients with locoregionally-advanced ASCC per year.

Biopsy of suspicious inguinal nodes was advocated in only 12 (11.8%) centers. Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is done in 28 (27.7%). Intensity modulated radiotherapy or similar techniques are used in 97%. The elective lymph node dose ranged from 30.6 Gy to 52.8 Gy, whereas 87% prescribed 50.4–55. 8 Gy (range: 30.6 to 59.4 Gy) to the involved lymph nodes. The dose to gross disease of cT1 or cT2 ASCC ranged from 50 to ≥60 Gy. For cT3 or cT4 tumors the target dose ranged from 54 Gy to more than 60 Gy, with 76 (75.2%) institutions prescribing 59.4 Gy. The preferred concurrent chemotherapy regimen was 5-FU/Mitomycin C, whereas 6 (6%) prescribed Capecitabine/Mitomycin C. HIV-positive patients are treated with full-dose CRT in 87 (86.1%) institutions. First assessment for clinical response is reported to be performed at 4–6 weeks after completion of CRT in 2 (2%) institutions, at 6–8 weeks in 20 (19.8%), and 79 (78%) institutions wait up to 5 months.

Conclusions

We observed marked differences in radiotherapy doses and treatment technique in patients with ASCC, and also variable approaches for patients with HIV. These data underline the need for an consensus treatment guideline for ASCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The standard treatment in anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC) is 5-FU and mitomycin C (MMC)-based chemoradiotherapy (CRT) [1,2,3]. Since the introduction of CRT by Nigro et al. [4] standard treatment has remained largely unchanged, despite technological advances in RT that facilitate better sparing of normal tissues to reduce acute and late toxicities [5].

Several international guidelines covering the staging and treatment of ASCC are available (ESMO-ESSO-ESSO, UK, Australasian, NCCN) [6,7,8,9] that are characterized by variability in dose prescription to the primary tumor as well as the elective and involved lymph nodes. Dosing recommendations to the primary tumor range from 50.4 to 60 Gy - in some guidelines according to T stage. Classic shrinking field technique as is reported in the NCCN and Australasian guidelines proposes a dose to the elective nodal volume from 30.6 or 36 Gy (for the inguinal region), and for simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) techniques to the elective lymph nodes, a dose of 40 to 45 Gy in 28 to 30 fractions [8, 9].

Also, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive patients – especially in men who have sex with men (MSM) – are at a significantly higher risk to develop ASCC [10], and these patients were excluded from all major randomized trials due to expected toxicities. Nevertheless, in the era of combined antiretroviral therapy several retrospective reviews indicate the feasibility of standard CRT with comparable outcomes [11,12,13].

As the incidence of ASCC is rising, especially due to the association with human papilloma virus infection (HPV) [14, 15], there is a need to harmonize treatment recommendations. To date, there are no S3-guidelines for the treatment of ASCC in German-speaking countries. As such, we conducted a pattern of care survey to gain insight into how patients with ASCC are treated in the clinical routine.

Methods

Survey

An anonymous questionnaire including 18 questions (16 single choice questions, 2 multiple choice questions) was created (Table 1), and an online survey was then generated using Google Forms® (Google, Mountain view, CA, USA). The link to the survey and the questionnaire PDF file for offline use was sent to 361 German Society of Radiation Oncology (DEGRO)-associated institutions, including German-speaking radiation oncology departments of 41 universities, 118 non-university institutions and 202 radiation oncology private practices in Germany, Austria and the German-speaking part of Switzerland. As the questions 8, 9 and 10 allowed individual answers regarding the prescribed radiation dose and all these individual answers covered dose ranges, we used the highest dose given for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Frequency distributions of responses for each question were calculated. The answers were also analyzed by type of institution (university department vs. non-university institution vs out-patient practices) using Pearson’s chi-squared test. All statistical analysis was performed using the R software package (Version 3.6) [16].

Results

We received 101 answers from 361 inquiries (28%), including 20 (19.8%) from university departments, 36 (35.6%) from non-university clinics and 45 (44.6%) from out-patient radiation oncology practices. A total of 28 (27.8%) institutions reported to treat more than 5 patients per year with early ASCC, defined as cT1-2N0M0, and 42 (41.6%) institutions treat more than 5 patients annually with locoregionally advanced ASCC (Table 2). Routine screening for infection with HIV for all patients is done in 28 (27.7%) institutions, and in additional 5 (4.9%) only male patients are screened. HIV positive patients are treated with standard CRT without dose reduction in 87 (86.1%) institutions, while 5 (4.9%) use a reduced dose of chemotherapy, while 5 (4.9%) do not prescribe concurrent chemotherapy at all.

Mandatory imaging for RT treatment planning includes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis in 86 (85%) institutions, 70 (69,3%) use a computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis, and 56 (55.4%) use endorectal ultrasound studies in addition to CT/MRI. Only 18 (17.8%) institutions apply a fluorodesoxyglucose-PET/CT for planning, 12 (11.8%) routinely perform a biopsy of suspicious inguinal lymph nodes, 44 (43.5%) never conduct a biopsy, whereas a biopsy is occasionally performed in 45 (44.5%) centers (Table 2).

We also evaluated the answers with regard to institution (university vs. non-university clinic vs. out-patient practice, Table 2). University hospitals treated significantly more patients with advanced ASCC, especially compared to out-patient practice (13, 65% vs. 17, 47% vs. 12, 27% for university vs. non-university clinic vs. out-patient practice, respectively; p = 0.02). Routine HIV-screening is done significantly more often in university clinics (11, 55% vs. 10, 28% vs. 7, 16% for university vs. non-university clinic vs. out-patient practice, respectively; p = 0.01).

Most institutions use intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) (24%) or rotational techniques (e.g. VMAT, RapidArc; tomotherapy; 73%) (Table 3). A large variability was observed regarding the prescribed radiation dose to clinical target volumes (Table 4). The dose to gross disease of cT1 or cT2 ASCC ranged from 50 to ≥60 Gy, with 83 (82.1%) using 54–59.4 Gy. For cT3 or cT4 tumors the target dose ranged from 54 Gy to more than 60 Gy, with 76 (75.2%) institutions prescribing 59.4 Gy. The doses to the elective lymph node CTV ranged from 30.6 Gy to 52.8 Gy. The dose range for the involved lymph node CTV was even greater, ranging from 30.6 to 59.4 Gy, but most institutions (88, 87.1%) prescribed doses from 50.4–55.8 Gy.

A simultaneously integrated boost (SIB) technique is used in 40 (39.6%) institutions, while a brachytherapy boost is used as alternative to a percutaneous boost in 15 (14.8%); 9 (8.9%) institutions use electrons for a percutaneous boost. Regarding the use of alternative boost techniques, we found that techniques like brachytherapy or electron boosts are mostly used in non-university clinics and the least used in out-patient practice (6, 30% vs. 15, 43% vs. 3, 7% for university vs. non-university clinic vs. out-patient practice, respectively; p < 0.01).

The standard 5-FU/Mitomycin C-based CRT is performed in 95 (94%) centers, whereas 6 (6%) use Capecitabine/Mitomycin C as concomitant chemotherapy. Consolidation chemotherapy is prescribed routinely in only 1 institution, whereas 11 (10.9%) institutions occasionally prescribe consolidation chemotherapy; 2 (2%) departments also prescribe induction chemotherapy on a case by case basis. There were no significant differences regarding radiotherapy technique and dose, or use of concurrent chemotherapy, between institutions.

Regarding the timepoint for assessing clinical response, 2 (2%) institutions use 4–6 weeks, 20 (19.8%) use 6–8 weeks, and 79 (78.2%) wait up to 5 months after end of treatment for final response assessment (Table 3). Routine evaluation of patient’s quality of life (QoL) and patient-reported outcome (PROMs) is performed in 27 (26.7%) institutions (Table 3).

Discussion

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first pattern of care survey for ASCC in German-speaking radiation oncology institutions. With regard to pretreatment staging modalities, MRI of the pelvis is mandatory in most institutions, whereas a FDG-PET/CT is done in a minority, likely due to the lack of reimbursement by health insurances in Germany. Nevertheless, previous data describe FDG-PET/CT as a helpful imaging modality as it can lead to up- and downstaging in 28% of patients [8, 17, 18]. Additionally, FDG-PET/CT can be of use in the detailed contouring of the target volume [19], which is very important in the era of IMRT as a geographical miss can have a large impact on prognosis [20]. A large discrepancy between institutions was observed for diagnostic biopsy of suspicious inguinal lymph nodes. The current NCCN guideline recommends considering fine needle aspiration biopsy for suspicious inguinal nodes [8] and the ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO guidelines reports that it is usually only performed for patients with palpable lymph nodes or those enlarged > 10 mm in imaging studies [6].

Routine screening for HIV is advocated by the current NCCN guidelines because of the higher incidence of ASCC in HIV-positive patients and the non-negligible number of HIV-infected patients in the United states that are not aware of their infection status [8]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend HIV screening for all patients in health care settings [21], whereas the European guidelines consider HIV screening as optional but recommended [6]. In our survey, routine screening is only offered in 27%, which certainly shows that improvement in this area is needed in order to improve patients care. Interestingly, 5% of institutions offer HIV testing routinely only to male patients. The reasoning behind must be the higher probability of male patients being HIV positive, nevertheless expanding this to all patients is recommended. Treating HIV-positive patients with standard CRT was thought to be associated with more toxicities due to the immune compromised state of these patients, nevertheless several retrospective series reported comparable toxicities for patients that are under combined antiretroviral therapy [11, 13]. The NCCN and ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO guidelines support standard CRT for HIV-positive patients that are under combined antiretroviral therapy, despite missing evidence from randomized studies [6, 8].

As reflected in the different guidelines (ESMO-ESSO-ESSO, UK, Australasian, NCCN) [6,7,8,9], we observed a rather large variability in the RT doses used for the primary tumor, as well as for involved and elective lymph nodes among the different German-speaking institutions. The ongoing PLATO umbrella trial, containing the ACT3, ACT4 and ACT5 trial, currently assesses the efficacy and toxicity of risk-adapted RT in ASCC [22]. ACT3 is a non-randomized phase II trial for patients with T1N0 tumors after local resection. Depending on resection margins, patients either receive no adjuvant therapy (margins > 1 mm) or receive adjuvant CRT with MMC and capecitabine and a total RT dose of 41.4 Gy. ACT4 is a randomized phase II trial in patients with T1/2 (up to 4 cm) N0 tumors. Patients in the standard arm receive MMC/capecitabine-CRT with 50.4 Gy to the tumor and 40 Gy to the elective nodal region, which is reduced to 41.4 Gy and 34.5 Gy, respectively, in the experimental arm. ACT5 recruits patients with advanced ASCC (T2N1–3 or T3/4Nany). There are three arms in this trial, the standard arm consists of MMC/capecitabine-CRT up to 53.2 Gy, while patients in both experimental arms are treated to a dose of either 58.8 or 61.6 Gy in 28 fractions. These studies will provide important data on the optimal risk-adapted RT dose for different risk-groups of ASCC.

Using IMRT instead of conventional 3D-RT has been adopted in the vast majority of German-speaking institutions (97%), which is in line with the recommendations of the NCCN and ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO guidelines [6, 8]. The use of simultaneously integrated boost (SIB) techniques to the primary tumor was common (40.5%) among our survey. Although there is no randomized evidence that supports the use of SIB in ASCC, the RTOG 0529 trial – a single armed phase 2 study that used a dose painting technique - showed a trend towards a more favorable toxicity profile [23]. The current British guidelines also recommend a dose painting approach with 53.2 Gy in 28 fractions (1.9 Gy/fx) for the gross tumor volume of locoregionally advanced ASCC [7]. As it was not included into the survey we cannot comment on the contouring guidelines that are used in the institutions. Alternative boost techniques like brachytherapy only play a role in a minority of institutions. Dose escalation was prominently tested in the ACCORD 03 phase 3 trial, which showed no benefit for escalation beyond 60 Gy [3]. However, a recently published pooled analysis of ACCORD 03 and the KANAL phase 2 trial revealed that total doses of beyond 60 Gy might be associated with a better colostomy free survival [24]. Note that approximately half of the patients in this analysis were treated with brachytherapy. Additionally, a retrospective review suggests a role for brachytherapy in patients with non-complete response after completion of CRT [25]. The use of consolidation chemotherapy in our survey is very low – in line with the current evidence that suggests no benefit for induction- or consolidation chemotherapy [1, 2].

Recent results of the ACT II trial showed that the best time-point for assessment of treatment response is 26 weeks upon initiation of CRT, i.e. approximately 5 months upon CRT completion [26]. In our survey, the majority of departments (79, 78.2%) has adopted this longer waiting period. Due to ambiguous wording of the question the interpretation of the answers is difficult. Our intention was to assess the timepoint when the decision for response versus persisting disease is made regardless of diagnostics used.

There are some limitations to our study. The low response rate could lead to a biased analysis. Possible reasons for this could have been a) outdated contact information b) tightly scheduled routine work leading to a lack of time and c) lack of interest in the topic. The wording of question 18 was suboptimal and make analysis difficult. At last, we have no information on the used contouring guidelines.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we observed several differences in radiotherapy doses and treatment techniques in ASCC, and also different management for HIV-positive patients among German-speaking radiation oncology institutions. These data further underline the need for a consensus treatment guideline for ASCC, which is currently prepared as S3 guideline in Germany and expected to be published in 2020.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASCC:

-

Anal squamous cell carcinoma

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention;

- CRT:

-

Chemoradiotherapy

- Gy:

-

Gray

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IMRT:

-

Intensity modulated radiotherapy

- MMC:

-

Mitomycin C

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- SIB:

-

Simultaneously integrated boost;

References

Gunderson LL, Winter KA, Ajani JA, Pedersen JE, Moughan J, Benson AB, et al. Long-term update of US GI intergroup RTOG 98-11 phase III trial for anal carcinoma: survival, relapse, and colostomy failure with concurrent chemoradiation involving fluorouracil/mitomycin versus fluorouracil/cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4344–51.

James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, Cunningham D, Myint AS, Saunders MP, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:516–24.

Peiffert D, Tournier-Rangeard L, Gérard J-P, Lemanski C, François E, Giovannini M, et al. Induction chemotherapy and dose intensification of the radiation boost in locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: final analysis of the randomized UNICANCER ACCORD 03 trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1941–8.

Nigro ND, Seydel HG, Considine B, Vaitkevicius VK, Leichman L, Kinzie JJ. Combined preoperative radiation and chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer. 1983;51:1826–9.

Pollom EL, Wang G, Harris JP, Koong AC, Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J, et al. The impact of IMRT on hospitalization outcomes in the SEER-Medicare population with anal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.01.006.

Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, Goh V, Peiffert D, Cervantes A, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO. 2014;40:1165–76.

Anal IMRT Guidance, http://analimrtguidance.co.uk/, Accessed 26 Sept 2019.

NCCN Guideline Anal Cancer, https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anal.pdf, Accessed 26 Sept 2019.

Ng M, Leong T, Chander S, Chu J, Kneebone A, Carroll S, et al. Australasian gastrointestinal trials group (AGITG) contouring atlas and planning guidelines for intensity-modulated radiotherapy in Anal Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2012;83:1455–62.

Colón-López V, Shiels MS, Machin M, Ortiz AP, Strickler H, Castle PE, et al. Anal Cancer risk among people with HIV infection in the United States. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36:68–75.

Martin D, Balermpas P, Fokas E, Rödel C, Yildirim M. Are there HIV-specific differences for Anal Cancer patients treated with standard Chemoradiotherapy in the era of combined antiretroviral therapy? Clin Oncol. 2017;29:248–55.

Blazy A, Hennequin C, Gornet J-M, Furco A, Gérard L, Lémann M, et al. Anal carcinomas in HIV-positive patients: high-dose chemoradiotherapy is feasible in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1176–81.

White EC, Khodayari B, Erickson KT, Lien WW, Hwang-Graziano J, Rao AR. Comparison of Toxicity and Treatment Outcomes in HIV-positive Versus HIV-negative Patients With Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anal Canal. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(4):386–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000172.

Ouhoummane N, Steben M, Coutlée F, Vuong T, Forest P, Rodier C, et al. Squamous anal cancer: patient characteristics and HPV type distribution. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:807–12.

Martin D, Rödel F, Balermpas P, Rödel C, Fokas E. The immune microenvironment and HPV in anal cancer: rationale to complement chemoradiation with immunotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1868:221–30.

R Development Core Team. R: A lanssguage and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. http://www.r-project.org.

Jones M, Hruby G, Solomon M, Rutherford N, Martin J. The role of FDG-PET in the initial staging and response assessment of Anal Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3574–81.

Martin D, Balermpas P, Winkelmann R, Rödel F, Rödel C, Fokas E. Anal squamous cell carcinoma - state of the art management and future perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;65:11–21.

Krengli M, Milia ME, Turri L, Mones E, Bassi MC, Cannillo B, et al. FDG-PET/CT imaging for staging and target volume delineation in conformal radiotherapy of anal carcinoma. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2010;5:10.

Koeck J, Lohr F, Buergy D, Büsing K, Trunk MJ, Wenz F, et al. Genital invasion or perigenital spread may pose a risk of marginal misses for intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) in anal cancer. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2016;11:53.

Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep. 2006;55 RR-14:1–17 quiz CE1–4.

Sebag-Montefiore D, Adams R, Bell S, Berkman L, Gilbert DC, Glynne-Jones R, et al. The Development of an Umbrella Trial (PLATO) to Address Radiation Therapy Dose Questions in the Locoregional Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:E164–5.

Kachnic LA, Winter K, Myerson RJ, Goodyear MD, Willins J, Esthappan J, et al. RTOG 0529: a phase 2 evaluation of dose-painted intensity modulated radiation therapy in combination with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C for the reduction of acute morbidity in carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:27–33.

Faivre J-C, Peiffert D, Vendrely V, Lemanski C, Hannoun-Levi J-M, Mirabel X, et al. Prognostic factors of colostomy free survival in patients presenting with locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: a pooled analysis of two prospective trials (KANAL 2 and ACCORD 03). Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2018;129:463–70.

Gryc T, Ott O, Putz F, Knippen S, Raptis D, Fietkau R, et al. Interstitial brachytherapy as a boost to patients with anal carcinoma and poor response to chemoradiation: single-institution long-term results. Brachytherapy. 2016;15:865–72.

Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, Meadows HM, Cunningham D, Begum R, Adab F, et al. Best time to assess complete clinical response after chemoradiotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a post-hoc analysis of randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:347–56.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Developed survey: DM,EF, JvdG; analyzed data: DM, EF; Wrote the manuscript: DM, EF, CR; All authors contributed to the review of the manuscript and all approved the final draft for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, D., von der Grün, J., Rödel, C. et al. Management of anal cancer patients – a pattern of care analysis in German-speaking countries. Radiat Oncol 15, 122 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-020-01539-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-020-01539-x