Abstract

Background

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of previous local treatment on lymphatic drainage patterns in ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) based on our data on re-operative sentinel lymph node biopsy (re-SLNB) for IBTR.

Methods

Between April 2005 and December 2016, re-SLNB using lymphoscintigraphy with Tc-99 m phytate was performed in 136 patients with cN0 IBTR. Patients were categorized into two groups: the AX group included 55 patients with previous axillary lymph node dissection; the non-AX group included 69 patients with previous SLNB and 12 patients with no axillary surgery. The whole breast irradiation (RT) after initial surgery had performed in 17 patients in the AX group and 27 patients in the non-AX group.

Results

Lymphatic drainage was visualized in 80% of the AX group and 95% of the non-AX group (P < 0.01). The visualization rate of lymphatic drainage was associated with the number of removed lymph nodes in prior surgery. In the non-AX group, lymphatic drainage was visualized in 96% of patients without RT and 93% with RT. Lymphatic drainage was observed at the ipsilateral axilla in 98% of patients without RT and in 64% with RT (P < 0.0001). Aberrant drainage was significantly more common in patients with RT than without RT (60% vs. 19%, P < 0.001); it was observed mostly to the contralateral axilla (52% vs. 2%, P < 0.0001). In the AX group, patients with previous RT showed decreased lymphatic drainage to the ipsilateral axilla compared to those without RT (29% vs. 63%, P < 0.05) and increased aberrant drainage to the contralateral axilla (64% vs. 5%, P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Lymphatic drainage patterns altered in re-SLNB in patients with IBTR and previous ALND and RT were associated with alterations in lymphatic drainage patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

While sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a well-established procedure for patients with clinically node-negative primary breast cancer [1,2,3,4], established guidelines for the management of axillary lymph nodes in patients developing ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) are lacking.

It is known that a sentinel lymph node (SLN) is sometimes observed in extra-axillary regions of IBTR cases because lymphatic drainage patterns are altered by previous treatments, such as axillary surgery and irradiation of the breast [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, assessment of the ipsilateral axilla alone may not be sufficient for staging IBTR.

According to a report on SLNB for patients with primary breast cancer, the visualization rate of lymphatic drainage was 97%, and lymphatic drainage was mainly observed to the ipsilateral axilla (96%) [9]. In a small study, aberrant drainage was reported to the internal mammary chain (IMC) (22%), intramammary region (7%), subclavicular region (3%), supraclavicular region (0.5%), and interpectoral region (2%) [9]. In contrast, a meta-analysis of re-operative SLNB (re-SLNB) for IBTR revealed a success rate of 71% for lymphatic mapping, markedly lower than that of SLNB in patients with primary breast cancer [10]. Aberrant drainage was observed in 43% of these patients, a much higher frequency than in patients with primary breast cancer. Although it is well known that previous axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) decreases the identification rate of SLNs for IBTR and increases aberrant drainage [5,6,7, 11], the impact of previous radiotherapy (RT) on re-SLNB remains largely unknown.

Because re-SLNB may provide useful information in determining adjuvant treatment for IBTR, we have performed re-SLNB for IBTR, using radioisotope techniques and preoperative lymphoscintigraphy to stage IBTR. The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate lymphatic drainage patterns in re-operative SLNs (re-SLNs) in association with prior local therapy in patients with IBTR.

Methods

The institutional clinical database was used to identify patients who developed IBTR and underwent re-SLNB between April 2005 and December 2016. The ethical review committee of the institute approved this study protocol (No.2018–1222). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Patients who underwent re-SLNB without preoperative lymphoscintigraphy, those with synchronous or metachronous bilateral breast cancer, and those lacking detailed information on previous surgeries were excluded. None of the patients had clinically metastatic lymph nodes, as examined by preoperative ultrasound. Fine needle aspiration cytology was performed if node metastasis was suspected by ultrasound.

The day before surgery, total 55.5 MBq (1.5 mCi) Tc-99 m phytate was injected at two intradermal sites at the tumor and at two peritumoral sites. Static images were obtained 1 h after the injection from 3 projections (anterior, 30 degrees anterior-oblique, and 60 degrees anterior-oblique views). Hot spots on the lymphoscintigram were regarded as re-SLNs. SPECT/CT was also performed in a subset of patients.

Patients were categorized into two groups according to their previous axillary surgeries: the non-AX group included patients with SLNB and no previous axillary surgery, and the AX group included those with ALND. Patients were further categorized based on the use of previous adjuvant RT.

A chi-squared test was applied to evaluate differences in lymphatic drainage patterns between the AX group and the non-AX group and between the RT group and the no RT group. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the number of removed nodes between different groups. The log-rank test was used to compare the disease-free interval (DFI), the interval from primary surgery to the diagnosis of IBTR, between the patients whose lymphatic drainage was visualized on lymphoscintigraphy and these whose lymphatic drainage was not visualized. GraphPad Prism v.5.04 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Between April 2005 and December 2016, 277 patients were identified who developed IBTR and underwent re-SLNB. Of the 277 patients, 141 were excluded according to the exclusion criteria, with 136 patients remaining in the analysis. The characteristics of the 136 patients are shown in Table 1. Median age at IBTR was 55 years. The median DFI was 67 months. Median follow-up period from the day of surgery for IBTR was 141 months.

Median age at primary surgery was 47 years. All patients had undergone breast-conserving surgery for their primary breast cancer. Sixty-nine and 55 patients had undergone SLNB and ALND, respectively, and 12 patients had no previous axillary surgery. Median number of lymph nodes removed at the primary surgery was 2 (1–6) in patients who had undergone SLNB and 20 (8–34) in patients who had undergone ALND. RT after breast-conserving surgery was performed in 44 patients. The whole breast irradiation dose was 42.5–50Gy with or without a boost dose of 10–16Gy in tumor beds. RT was not performed when surgical margins were entirely free of cancer, as confirmed by a precise pathological examination according to our institutional treatment protocol [12].

Visualization of lymphatic drainage patterns on lymphoscintigraphy

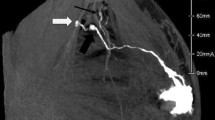

Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy identified at least one SLN, defined as re-SLN, in 121 (89%) of the 136 patients (Table 2). Lymphatic drainage was visualized at the ipsilateral axilla in 74%. Some patients showed multiple patterns of lymphatic drainage. Aberrant drainage was visualized in five regions: IMC, supraclavicular, intramammary, contralateral axilla, and contralateral IMC (Table 2). A representative case of aberrant drainage is shown in Fig. 1. DFI was shorter in patients whose lymphatic drainage was visualized on lymphoscintigraphy compared with patients whose lymphatic drainage was not visualized (60 vs. 129 months, P < 0.05). No difference in visualization rate was observed according to hormone receptor status and HER2 status for both primary cancer and IBTR (Table 3).

Lymphoscintigraphy and SPECT/CT images of aberrant lymphatic drainages. (A) Lymphatic drainages were visualized at the contralateral axilla (arrow a) and the ipsilateral internal mammary chain (IMC) (arrow b) in a case with left IBTR. SPECT/CT revealed hot spots at the right axillary region (B) and the left IMC (C)

Impact of axillary surgery on lymphatic drainage patterns

Lymphatic drainage patterns were compared according to previous axillary surgeries. The visualization rate of lymphatic drainage was higher in the non-AX group (95%) than in the AX group (80%) (P < 0.01) (Table 4). The visualization rate was associated with the number of lymph nodes which had been removed in the prior surgery (Table 5). The median number of removed lymph nodes in the prior surgery was fewer in patients whose lymphatic drainage was visualized on lymphoscintigraphy compared with patients whose lymphatic drainage was not visualized (8 vs. 16 nodes, P < 0.05). Lymphatic drainage was visualized in all 12 patients who had not undergone previous axillary surgery (Table 5). The visualization rate was markedly low (71%) in patients in whom 20 or more lymph nodes had been removed in prior surgery (Table 5).

Lymphatic drainage was visualized at the ipsilateral axilla in 87% of patients in the non-AX group and in 52% in the AX group (P < 0.001, Table 4). Aberrant drainage was visualized significantly more frequently in the AX (75%) than in the non-AX (33%) group (P < 0.0001, Table 4). Lymphatic drainage was visualized at the IMC in 16% of the non-AX group and 55% of the AX group (P < 0.001, Table 4). Although axillary dissection had been performed in the AX group, re-SLNs were visualized in the ipsilateral axilla in 52% of patients: at level I and II of the axillae in seven patients, in the Rotter space in ten patients, and at level III of the axilla in three patients. In three patients in the non-AX group, re-SLNs that were visualized by lymphoscintigraphy failed to be identified during surgery because of the poor responses of the gamma-ray detection probe.

Impact of adjuvant radiotherapy on lymphatic drainage patterns

In the non-AX group, lymphatic drainage was visualized in 96% of patients without RT and 93% of those with RT (Table 6a). Re-SLNs were visualized at the ipsilateral axilla in 98% of the patients without RT and in 64% of those with RT (P < 0.0001, Table 6a). Aberrant drainage was significantly more frequent in patients with RT (60%) than in those without RT (19%) (P < 0.001). Notably, more than half (52%) of patients with RT showed aberrant drainage to the contralateral axilla, whereas only 2% of those without RT did (P < 0.0001). No re-SLNs were visualized in the supraclavicular region in the non-AX group.

In the AX group, lymphatic drainage was visualized in 82% of patients with RT and 79% of those without RT (Table 6b). Aberrant drainage to the contralateral axilla was observed in nearly two-thirds (64%) of patients with RT but in 5% of those without RT (P < 0.0001, Table 6b).

Discussion

The present study revealed that the previous local treatment, not only axillary surgery but also RT, had impact on lymphatic drainage patterns in patients with IBTR. First, we confirmed the impact of previous axillary surgery on lymphatic drainage patterns. Next, we demonstrated that previous RT resulted in aberrant lymphatic drainage in 60% of patients in the non-AX group and in 93% in the AX group.

We found that the visualization rate of re-SLN was almost the same regardless of previous RT while it was reduced by axillary surgery (Tables 4, 6). In addition, RT reduced the ipsilateral axillary drainage from 98 to 64% and increased the aberrant drainage, especially to the contralateral axilla both in the AX group and in the non-AX groups. There were a few studies that examined the impact of RT on lymphatic drainage patterns and showed that RT had no effect on the identification rate of re-SLNs, in concordance with our study [5, 13]. Interestingly, in a study with 22 patients with breast cancer who had previously undergone mantle field radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the detection rate of SLNs was 86%, which was less than that in previously untreated patients with breast cancer (97%) [14]. The visualization rate of SLNs at the ipsilateral axilla was lower than that in patients with previously untreated breast cancer (86% vs. 92%), and SLNs were more often found outside the axilla (41% vs. 33%), especially at the IMC (32% vs. 21%) [14]. The discrepancy between our results and those of the patients receiving mantle field radiation could be attributed to the difference in the irradiated fields and doses. In the study of mantle field radiation, the lymphatic regions in the neck, bilateral axilla, and mediastinum received a radiation dose of 36–40 Gy [14]. The medial and upper outer quadrants of the breast were also exposed to radiation. In contrast, the whole breast irradiation dose was 42.5–50Gy in the present study, and some patients were also given a boost dose of 10–16Gy in tumor beds. Considering that lymphatic drainage had been damaged by irradiation and aberrant lymphatic drainage did not involve the irradiated area, it was understandable that lymphatic drainage to the IMC increased after patients received mantle field irradiation and that lymphatic drainage to the contralateral axilla increased in those with previous whole breast irradiation.

According to our results, in patients with IBTR with previous SLNB and non-RT, lymphatic drainage remains mostly in the ipsilateral axilla, and these patients will be suitable for re-SLNB. On the other hand, re-SLNs were visualized at the contralateral axilla in more than 20% of the whole population (Table 2). Although there are some reports showing the feasibility of the re-SLNB procedure [7, 15,16,17,18], the clinical significance of re-SLNB has not yet been confirmed. In addition, it is further complicated in cases with aberrant SLNs. Metastasis to the contralateral axilla is regarded as distant metastasis in primary breast cancer [19], but in patients with IBTR, the contralateral axilla may be considered a regional lymph node if re-SLNs are identified in the contralateral axilla [20]. Although there are no guidelines for management of contralateral SLN and positive contralateral SLN, pathological results in contralateral SLN may be useful in deciding adjuvant treatment for IBTR [21]. Further studies to clarify the clinical significance of aberrant SLNs are required.

The major limitation of this study is the retrospective design with a small number of patients. In particular, the number of patients who had received previous RT was small and not enough to make any conclusion on the impact of RT on lymphatic drainage patterns. In addition, this study focuses only on lymphatic drainage patterns and does not examine the success rate of SLNB or pathological results of re-SLNs. Thus, the clinical significance of re-SLN examination is not clear. Another limitation is the lack of information on patient outcomes. It is important to examine the clinical outcomes of patients in association with treatment, including surgical procedures to determine the optimal treatment strategy. This is especially important in patients with aberrant lymphatic drainage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, lymphatic drainage patterns altered in re-SLNB in patients with IBTR and previous ALND and RT were associated with alterations in lymphatic drainage patterns. More studies focusing on the clinical usefulness of re-SLNB, including outcomes after re-SLNB, are warranted.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ALND:

-

Axillary lymph node dissection

- DFI:

-

Disease-free interval

- IBTR:

-

Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence

- IMC:

-

The internal mammary chain

- re-SLNB:

-

Re-operative sentinel lymph node biopsy

- re-SLNs:

-

Re-operative sentinel lymph nodes

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- SLN:

-

Sentinel lymph node

- SLNB:

-

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

References

Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:546–53.

Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:599–609.

Kim T, Giuliano AE, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast carcinoma: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;106:4–16.

Schrenk P, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W. Sentinel lymph-node biopsy compared to axillary lymph-node dissection for axillary staging in breast cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol WB Saunders. 2001;27:378–82.

Port ER, Garcia-Etienne CA, Park J, et al. Reoperative sentinel lymph node biopsy: a new frontier in the management of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2209–14.

van der Ploeg IMC, Oldenburg HSA, Rutgers EJT, et al. Lymphatic drainage patterns from the treated breast. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1069–75.

Uth CC, Christensen MH, Oldenbourg MH, et al. Sentinel lymph node dissection in locally recurrent breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2526–31.

Koizumi M, Koyama M, Tada K, et al. The feasibility of sentinel node biopsy in the previously treated breast. Eur J Surg Oncol WB Saunders. 2008;34:365–8 Available from.

Estourgie SH, Nieweg OE, Valdés Olmos RA, et al. Lymphatic drainage patterns from the breast. Ann Surg. 2004;239:232–7.

Maaskant-Braat AJG, Voogd AC, Roumen RMH, et al. Repeat sentinel node biopsy in patients with locally recurrent breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:13–20.

Ahmed M, Baker R, Rubio IT. Meta-analysis of aberrant lymphatic drainage in recurrent breast cancer. BJS John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2016;103:1579–88.

Sakai T, Iwase T, Teruya N, et al. Surgical excision without whole breast irradiation for complete resection of ductal carcinoma in situ identified using strict, unified criteria. Am J Surg Elsevier. 2017;214:111–6.

Intra M, Trifirò G, Galimberti V, et al. Second axillary sentinel node biopsy for ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence. BJS. 2007;94:1216–9.

van der Ploeg IMC, Russell NS, Nieweg OE, et al. Lymphatic drainage patterns in breast Cancer patients who previously underwent mantle field radiation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2295–9.

Intra M, Viale G, Vila J, et al. Second axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast tumor recurrence: experience of the European Institute of Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2372–7.

Ugras S, Matsen C, Eaton A, et al. Reoperative sentinel lymph node biopsy is feasible for locally recurrent breast Cancer, but is it worthwhile? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:744–8.

Karanlik H, Ozgur I, Kilic B, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and aberrant lymphatic drainage in recurrent breast cancer: findings likely to change treatment decisions. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:796–802.

Maaskant-Braat AJG, Roumen RMH, Voogd AC, et al. Sentinel node and recurrent breast Cancer (SNARB): results of a Nationwide registration study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:620–6.

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American joint committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–4.

Moossdorff M, Vugts G, Maaskant-Braat AJG, et al. Contralateral lymph node recurrence in breast cancer: regional event rather than distant metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1128–36.

Lizarraga IM, Scott-Conner CEH, Muzahir S, et al. Management of Contralateral Axillary Sentinel Lymph Nodes Detected on lymphoscintigraphy for breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3317–22.

Acknowledgements

We thank all staffs working for the Breast Oncology Center of Cancer Institute Hospital of JFCR. We also express our gratitude to our data manager, Rie Gokan for her support.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concepts and study design: TI. Data acquisition: AS, TS, FK, KK, AO. Quality control of data and algorithms: TS, MK, RH, FA. Data analysis and interpretation: AS, TS, TI. Manuscript editing: AS, TS, MT, TU. Manuscript review: TU, SO. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The ethical review committee of the Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research approved this study protocol (No.2018–1222).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, A., Sakai, T., Iwase, T. et al. Altered lymphatic drainage patterns in re-operative sentinel lymph node biopsy for ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence. Radiat Oncol 14, 159 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1367-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1367-0