Abstract

Background

The aim of this study is to evaluate the radiobiological impact of Acuros XB (AXB) vs. Anisotropic Analytic Algorithm (AAA) dose calculation algorithms in combined dose-volume and biological optimized IMRT plans of SBRT treatments for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.

Methods

Twenty eight patients with NSCLC previously treated SBRT were re-planned using Varian Eclipse (V11) with combined dose-volume and biological optimization IMRT sliding window technique. The total dose prescribed to the PTV was 60 Gy with 12 Gy per fraction. The plans were initially optimized using AAA algorithm, and then were recomputed using AXB using the same MUs and MLC files to compare with the dose distribution of the original plans and assess the radiobiological as well as dosimetric impact of the two different dose algorithms. The Poisson Linear-Quadatric (PLQ) and Lyman-Kutcher-Burman (LKB) models were used for estimating the tumor control probability (TCP) and normal tissue complication probability (NTCP), respectively. The influence of the model parameter uncertainties on the TCP differences and the NTCP differences between AAA and AXB plans were studied by applying different sets of published model parameters. Patients were grouped into peripheral and centrally-located tumors to evaluate the impact of tumor location.

Results

PTV dose was lower in the re-calculated AXB plans, as compared to AAA plans. The median differences of PTV(D95%) were 1.7 Gy (range: 0.3, 6.5 Gy) and 1.0 Gy (range: 0.6, 4.4 Gy) for peripheral tumors and centrally-located tumors, respectively. The median differences of PTV(mean) were 0.4 Gy (range: 0.0, 1.9 Gy) and 0.9 Gy (range: 0.0, 4.3 Gy) for peripheral tumors and centrally-located tumors, respectively. TCP was also found lower in AXB-recalculated plans compared with the AAA plans. The median (range) of the TCP differences for 30 month local control were 1.6 % (0.3 %, 5.8 %) for peripheral tumors and 1.3 % (0.5 %, 3.4 %) for centrally located tumors. The lower TCP is associated with the lower PTV coverage in AXB-recalculated plans. No obvious trend was observed between the calculation-resulted TCP differences and tumor size or location. AAA and AXB yield very similar NTCP on lung pneumonitis according to the LKB model estimation in the present study.

Conclusion

AAA apparently overestimates the PTV dose; the magnitude of resulting difference in calculated TCP was up to 5.8 % in our study. AAA and AXB yield very similar NTCP on lung pneumonitis based on the LKB model parameter sets we used in the present study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The goal of radiation therapy is to optimize therapeutic ratios by delivering tumoricidal doses to targets while maximally sparing organs-at-risk (OARs). Mostly, the quality of a radiation treatment plan is judged by isodose distribution and dose-volume-histograms (DVH). Typically the biological outcomes in terms of tumor control and normal tissue complication are not estimated when evaluating a plan. Significant progress and contributions to our understanding and modeling of volume effects for both normal and tumor tissues started in the 1980s with the advent of modern three dimensional treatment planning techniques. Models for estimating the tumor control probability(TCP) and normal-tissue complication probabilities (NTCP) were proposed in the late 1980s [1–8]. Even though dose-volume techniques are a mainstay of current clinical treatment planning optimization, biological optimization using complication probability models in intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) planning has shown potential for reducing radiation-induced toxicity [9–11]. The current study used combined biological optimization and dose-volume optimization to take advantage of using radiobiological models and at the same time also keep the “important” dose-volume characteristics. The report of AAPM Task Group 166 [12] recommends that dose-volume constraints and the biologic optimization function be used together for optimization.

In 2005, Eclipse TPS released the Analytical Anisotropic Algorithm (AAA) [13]. AAA is a convolution–superposition-based photon beam dose computation algorithm. This algorithm was quickly and widely adopted for clinical use. More recently, Varian Eclipse TPS implemented another dose calculation algorithm, Acuros XB Advanced Dose Calculation (AXB), which uses a deterministic grid-based Boltzmann equation solver (GBBS or the discrete ordinates method). The GBBS [14, 15] explicitly solves the linear Boltzmann transport equation (LBTE), which is the governing equation that describes the macroscopic behavior of ionizing particles (neutrons, photons, electrons, etc) as they travel through and interact with matter. The GBBS then iteratively solves the radiation transport problem within specified volumes to compute radiation doses. AXB was first published by Vassiliev et al. [16] and has been considered to be similar to classic Monte Carlo methods for accurate modeling of dose deposition in heterogeneous media [16–18].

Among the numerous studies comparing the dosimetric differences between plans calculated with conventional algorithms (pencil beam type and convolution-superposition type) vs. with advanced algorithms (Monte Carlo type and GBBS type) [19–26], lung SBRT has been shown as the treatment where the differences due to dose algorithms are among the most significant, hence necessitating the adoption of the more advanced algorithms. This is due to the low density lung tissue and the high risk of normal tissue toxicity in hypofractionated treatments like SBRT. Compared with the very large dosimetric differences found between pencil beam type algorithms and advanced algorithms, smaller differences were seen between convolution-superposition typealgorithms such as AAA and advanced algorithms. Improved accuracy with advanced algorithms was always observed and deemed necessary in some cases. Pertaining to the two dose algorithms investigated, studies [19, 20] have illustrated that AXB is more accurate in modelling the radiation transportation and dose deposition in the patient. However, those studies were focused purely on dosimetric comparisons between AAA and AXB algorithms. The impact of these two algorithms on biological indices has not been thoroughly studied. To date, the radiobiological impact of AAA and AXB dose computation algorithms on lung tumor treatment plans, where the impact of dose algorithms would be prominent due to the low density lung tissue, has not been published. Furthermore, planning techniques in the existing literature investigating dosimetric differences between the conventional and advanced dose algorithms on lung SBRT were predominantly based on physical dose volume constraints. In this paper, we have retrospectively planned 28 stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients using combined dose-volume optimization and biological optimization provided by a Varian Eclipse (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) planning system (V11). Dose computation was performed alternatingly with AAA (V11) and AXB (V11) algorithms on these plans optimized with AAA. The tumor control probability (TCP) and normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) on normal lung tissue (pneumonitis ≥ 2) from AAA and AXB plans were evaluated using the Eclipse biological evaluation module (V1.4).

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the University of Arkansas Medical Science Institutional Review Board (FWA00001119).

Treatment planning

Computed tomography (CT) data from 28 patients with Stages I or II inoperable NSCLC previously treated using SBRT were selected for this study. We have divided the patients into two categories based on tumor location; peripheral and centrally located. This distinction was made due to the fact that the initial experience of SBRT in inoperable lung cancer reported increased toxicity for centrally located tumors [27]. A separate cooperative trial was then designed to explore different fractionation schemes for centrally located tumors [28]. Centrally located tumors are those located either within 2 cm of the airway (6 patients), or touch the pericardial pleura (2 patients), or adjacent to mediastinum (1 patient). The rest of the tumors were considered peripheral (19 patients). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A four-dimensional computed tomography (4DCT) was acquired for each patient. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) and average intensity projection CTs were reconstructed from the 4DCT. Internal target volume (ITV) was contoured using the MIP by one physician, and planning target volume (PTV) was generated by applying a 0.5 cm isotropic margin to the ITV. Each of the following structures was contoured using the average intensity projection CT by the same physician for every patient: bilateral lungs excluding ITV, spinal cord, esophagus, and heart. A chest wall (CW) structure was also contoured as a 2 cm two-dimensional expansion of the ipsilateral lung excluding the lung volume and the mediastinal soft tissue as described by Mutter et al [29]. The treatment planning was carried out on the average intensity projection CT image set. In order to obtain a conformal dose distribution, two ring structures around the PTVwere also generated. These rings are pseudo planning structures used in dose-volume optimization to conform dose to the target and reduce dose to normal tissue. Ring1 was defined as a 1 cm width ring structure with a 4 mm gap to the PTV. Ring 2 was defined from outward of Ring1 to the body surface and extended 3 cm superior/inferior to the PTV.

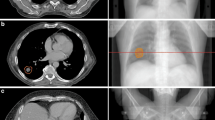

These 28 patients previously treated with SBRT were retrospectively planned using Varian Eclipse TPS (V11) with an IMRT sliding window technique. The total dose prescribed to the PTV was 60 Gy with 12 Gy per fraction. Plans were generated on each patient using 9 coplanar 6 MV beams using a True Beam with an HD120 MLC (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). The beam angles were chosen to best cover the PTV, while maximally sparing lung and other critical structures. The isocenter was placed at the center of the PTV. All plans used combined dose-volume histogram and radiobiological optimization to generate the optimal fluence map. The starting dose-volume and biological optimization cost function parameters used in the present study are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. After the initial optimization run, each plan was evaluated and fine-tuned by adjusting the physical dose constraints according to the desired dose distribution. After obtaining the optimized fluence map, the MLC leaf motion and final dose to water were computed using AAA. The treatment plan was normalized such that 95 % of the PTV is covered by the prescribed dose. The plan was evaluated by the same physician in order to ascertain that it met the institutional OAR dose constraints as listed in Table 4. Finally the plan was recalculated using AXB with dose to medium using the same MU and MLC patterns. The calculation grid was set at 0.25 cm for both AAA and AXB algorithms. A process flow diagram from the CT acquisition to the final AAA- and AXB-calculated plans is shown in Fig. 1.

TCP calculation

The Poisson Linear-Quadatric (PLQ) model was used for estimating the tumor control probability. The PLQ model [6] is derived from the linear-quadratic cell survival model using the Poisson distribution:

Where ɣ is the normalized dose–response gradient, D 50 represents the dose yielding 50 % TCP for a given end point, and EQD 2 is the equivalent dose given in 2 Gy fractions and was calculated using equation 2 [30]:

Where D is the cumulative dose and d is the dose of a single fraction.

The TCP model parameter values were originally obtained by fitting models on clinical data and are therefore dependent on various factors such as patient group, type of treatment, and dose algorithm etc [31]. The range of published D 50 on lung treatment was fairly large; Willner et al. [32] converted the total physical dose to 2-Gy fractionation dose equivalent and reported D 50 Values of 74.5 Gy for 24 month local control and Martel et al. [33] studied plans with 1.8 – 2.0 Gy per fraction and reported D 50 values of 72 and 84.5 Gy for 24 and 30 month local control on NSCLC. While Guckenberger et al. [34] reported a biologic effective dose D 50 of 42.3 Gy for 36 month local control. In the work of Guckenberger et al., the patient population was primarily pulmonary metastases. This may partially explain why in their study, D 50 was smaller than the D 50 ’s reported by the other groups [32, 33] where the studies were on NSCLC patients. Therefore, the higher end of D 50 range may be more applicable to our NSCLC cohort. Table 5 summarizes the TCP parameters that we used in the present study. Here we made an approximation that the physical dose of Martel et al. study is the same as EQD 2 since 1.8 – 2 Gy per fraction was used in their study. After all the treatment plans were computed with both AAA and AXB, the plans were evaluated using the Eclipse biological evaluation module (V1.4), where the DVHs were corrected to 2-Gy fractionations according to the LQ model. An α/β of 10Gy was used.

NTCP calculation

The Lyman-Kutcher-Burman (LKB) model was used for estimating normal tissue complication probability on lung pneumonitis. The LKB model is based on a Probit function [1, 3–5]:

where

The parameter m and D 50 represent the slope of the sigmoid dose response curve and the dose for a complication rate of 50 %, respectively. EUD is the equivalent uniform dose and is calculated as [35]:

Where v i is the partial volume with absorbed dose EQD 2,i and n is the dose-weighting factor, which defines the risks associated with partial organ volume uniform irradiation.

In the present study, the NTCP values for lung pneumonitis grade ≥ 2 were calculated using the LKB model. Several studies have reported estimates of the model parameters obtained from different clinical studies. A study from Burman et al. [4] was based on treatment plans in which no density correction was performed. Later, Seppenwoolde et al. [36] and Kwa et. al [37] presented difference model parameters obtained from density corrected treatment plans. We applied these three sets of model parameters in this study to investigate the influence of the model parameter uncertainty on NTCP. In addition, we also studied the influence of α/β ratios by applying two different α/β ratios for normal lung tissue; 1.3 Gy from the recent study of Scheenstra et al. [38] and 3 Gy as the standard normal tissue value.

Results and discussion

A comparison of the total physical dose DVHs of the ITV, PTV and OARs for a typical patient plans calculated using the AAA and AXB dose algorithms is shown in Fig. 2. Doses to PTV are generally higher in AAA-calculated plans than AXB-recalculated plans, similar to previous studies [24–26]. A comparison of total physical dose to ITV and PTV calculated using AAA or AXB dose algorithm for both peripheral tumor and centrally-located tumor patients is given in Table 6. A non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test [39] was used to calculate the p-value with p < 0.05 taken as significant. It appears that lower doses to PTV (D95%) and PTV (mean) in the re-calculated AXB plans, as compared to AAA plans. The median differences of PTV (D95%) were 1.7 Gy (range: 0.3, 6.5 Gy; p < <0.01) and 1.0 Gy (range: 0.6, 4.4 Gy; p < < 0.01) for peripheral tumor and centrally-located tumor patients, respectively. The median differences of PTV (mean) were 0.4 Gy (range: 0.0 to 1.9 Gy; P <0.05) and 0.9 Gy (range: 0.0, 4.3 Gy; P <0.05) for patients with peripheral tumors and centrally-located tumors respectively. As shown in Table 6, the difference in the calculated mean dose to ITV is not statistically significant. Here we need to note that our dose distribution was calculated on an average CT generated on a 4DCT scan. There are potential limitations on dose calculation on a static CT of a moving target. On an average CT, a significant fraction of the planning target was represented by low density lung tissue to where the optimizer tried to deliver a higher fluence in order to achieve target dose coverage. Studies on lung SBRT [40, 41] have shown that calculations on static CT underestimated the target dose, as compared to 4D calculations where the dose was computed in a respiratory-correlated CT.To keep the study consistent, the TCP parameters used for analysis in the present study were also obtained from non- respiratory-correlated CT plans.

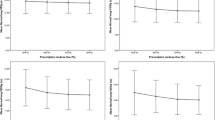

To study the influence of different model parameters on the calculated TCP difference between AAA and AXB plans (ΔTCP), we have applied the Willner et al. and Martel et al. parameter sets for 24 months local control listed in Table 5. Very similar median ΔTCP for 24 months local control were found; for peripheral tumors, 0.5 % (range: 0.1, 2.4 %) and 0.2 % (range: 0.0, 1.9 %), and for centrally-located tumors, 0.5 % (range: 0.2, 1.3 %) and 0.2 % (range: 0.1, 0.8 %) when using Martel et al. and Willner et al. parameter sets, respectively. Figure 3 shows the TCP values from both AAA and AXB plans. The TCP values were found to be lower in AXB-recalculated plans compared with those of AAA-calculated plans. For 30 months local control, the median ΔTCP were1.6 % (range: 0.3, 5.8 %) on peripheral tumor patients and 1.3 % (range: 0.5, 3.4 %) on centrally-located tumor patients. The lower TCP values from the AXB-recalculated plans are associated with a lower PTV dose coverage which is mainly due to the difficulty of the AAA algorithm to properly manage the lateral scattering in low-density media. Figure 4 shows the TCP (30 month local control) differences between AAA and AXB plans (ΔTCP) vs. the total physical dose differences of PTV (D95%) in the AAA and AXB plans (ΔD95%). It clearly shows that ΔTCP increases as ΔD95% increases. The TCP difference can be as large as 5.8 % on the case with a 6.5 Gy total physical dose (EQD 2 of 11.9 Gy) difference in D95%. Therefore, we recommend using the most accurate dose calculation algorithm. A smaller ΔTCP for 24 months local control was found compared with ΔTCP for 30 month local control. This may be because the median TCP values for 24 months local control on both AAA and AXB plans were approaching 100 %, even in the AXB-recalculated plans where the PTV dose coverage was lower than the AAA-calculated plans. For peripheral tumors, 97.7 % (range: 96.0, 98.5 %) and 99.6 % (range: 97.9, 99.8 %), and for centrally located tumors, 98.0 % (range: 97.1, 98.7 %) and 99.5 % (range: 98.9, 99.8 %) when using the Martel et al. and Willner et al. parameter set, respectively. Therefore, no substantial ΔTCP can be observed due to the slow slope of the TCP curve at this flat region. While for 30 months local control, the TCP values from AXB-recalculated plans were 87.1 % (range: 83.6, 90.4 %) and 87.8 % (range: 85.0, 91.5 %) for peripheral and centrally-located tumors, respectively. With this level of TCP values, the TCP model was able to show better discriminate between the dose calculations algorithms.

TCP calculated using Martal et al parameter set on PTV of AAA and AXB plans. a) and b) were calculated using the Willner et al. 24 months local control parameters, c) and d) were calculated using the Martel et al. 24 months local control parameter set, and e) and f) were calculated using the Martel et al. 30 months local control parameter set

In addition, we also studied the relationship between ΔTCP and the PTV size as well as the influence of tumor location on ΔTCP. Figure 5 shows the ΔTCP (30 months local control) vs. PTV size for both peripheral tumors and centrally-located tumors, with no trend observed. Figure 6 shows the box plot of the ΔTCP (30 months local control) comparison between peripheral tumors and centrally-located tumors. The group with peripheral tumors shows a slightly larger median ΔTCP (1.6 %), compared to the group with centrally-located tumors (1.3 %). However, this is not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.86. The dose distribution on PTV depends on a complex set of factors such as the beam angle, the location of tumors relative to low density media in the beam path etc. We have not observed obvious trends of ΔTCP with tumor size and locations within the present study group.

The median and range of Lung pneumonitis NTCP of AAA and AXB plans are listed in Table 7. The model parameters used are also listed in Table 7. Unless otherwise indicated an α/β of 1.3Gy [38] was used. AAA and AXB plans yield very similar NTCP values for both peripheral and centrally-located tumors. The median NTCP and ΔNTCP values are slightly larger in the group with centrally-located tumors, as compared to the group with peripheral tumors. In centrally-located tumors, the critical structures such as esophagus and heart are adjacent to the PTV. In order to spare heart and esophagus, the plan pushes more doses to the normal lung tissue in centrally-located tumor cases. This translates into a slightly sensitive change in NTCPs between the AAA and AXB plans for the group with centrally-located tumors. However, the NTCP difference between the centrally-located tumor group and the peripheral tumor group is not statistically significant (p-value of 0.40).

Figure 7 shows a box plot of the lung NTCP using three different LKB model parameter sets on AXB-recalculated treatment plans. The Burman et al. parameter set predicted the smallest NTCP, the Seppenwoolde et al. parameter set predicted largest NTCP, while Kwa et al. parameter set predicted between the other two parameter sets. Interestingly, in two centrally-located tumor cases, the Burman et al. parameter set predicted much larger NTCP values compares to the other two parameter sets. That is because the Burman et al. parameter set used a much sharper slope of the response curve compared with the other two parameter sets, which results in a more dose-sensitive NTCP prediction. However, when we studied the influence of different model parameter sets on the ΔNTCP, it did not change our conclusion that AAA and AXB plans yield very similar NTCP values. All the ΔNTCP remains <1 % except one outlier, a centrally-located tumor patient with the largest PTV size (144.9 cc), whose ΔNTCP was 5.4 % when using the Burman et al. parameter set to calculate,while values <1 % were obtained when using the other two parameter sets. The small ΔNTCP might be because that the NTCP models cannot discriminate between the dose calculation algorithms at these low NTCP value regions. We also studied the influence of α/β ratios using the Seppenwoolde parameter set with the results also shown in Table 7. Although the smaller α/β ratio (1.3 Gy) predicted slightly larger lung NTCP compared to with the α/β of 3 Gy, again it showed a very minimal influence on ΔNTCP.

The mean lung dose (MLD) has been widely used as a simple and effective metric for probability of pneumonitis [42]. In the present study, we have studied the relationship between the ΔNTCP and the MLD difference between AAA and AXB plans (ΔMLD). No obvious trend was observed. We also studied the correlation between the ΔNTCP and the PTV size with all three LKB model parameter sets and with two different α/β ratios. No correlation was observed.

Although we could not find published literature to make direct comparisons against our current study on SBRT lung plans, it is relevant to mention previous studies on the influence of dose calculation algorithms on the predicted TCP and NTCP values [31, 43, 44], these studies revealed some potential differences in TCP/NTCP values depending on the calculation algorithm used. Nielsen et al. [43] showed an estimated NTCP value for pneumonitis that varied 4 % across the six investigated dose algorithms. Bufacchi et al. [44] reported that the NTCP value from AAA-calculated plans was lower than that from pencil beam-calculated plans in most treated sites. Petillion et al. [31] reported lower TCP and NTCP predictions when using advanced algorithms. Since our fractionation scheme and studied algorithms were much different from these published works, direct comparison cannot be meaningfully made between our findings and their results. The radiobiological indices impact of AAA and ABX dose computation algorithms were published by Rana et al. [45] and Padmanaban et al. [46]. The study of Rana et al concluded that both AAA and AXB predicted comparable NTCP and TCP values for low-risk prostate cancer plans. However, in Padmanaban et al. study on esophagus cancer, where it also involves complex tissue heterogeneities, a difference in TCP between 1.2 % and 3.1 % was found. The study of Petillion et al. [31] reported a 0.3 % lower TCP on breast in AXB plans compared with AAA plans.

It should be stated that there are large uncertainties in the biological models used and its associated parameters.The published TCP/NTCP model parameters that we used were obtained from studies that used different treatment techniques and dose algorithms from the present study. This would introduce some uncertainties too. In addition, some studies have suggested that the LQ model may overestimate the radiobiological effect at the dose level commonly used in SBRT [47]. Conversely, results from our group and others suggests that the LQ model may actually underestimate the cell killing expected at higher SBRT doses if a significant amount of vascular damage and indirect cell death occurs [48, 49]. Whatever the case, it certainly seems appropriate to only treat the findings of the current study as a relative comparison between the different dose calculation algorithms rather than studying the absolute expected values. There is likely a lot more biological information that could be added to the model to make it more truly a biological optimization and evaluation. As more clinical data are collected, it may help in the formulation of methods to predict biophysical response and result in more accurate predictions of TCP and NTCP.

Conclusion

In this study, AXB-recalculated plans yielded lower TCP than the AAA-calculated plans. The lower TCP is associated with the lower PTV coverage in AXB-calculated plans. The maximum 11.9 Gy EQD 2 dose of ΔD95% in our patient cohort corresponds to up to 5.8 % ΔTCP for 30 months local control.AAA-calculated and AXB-recalculated plans yield very similar NTCP values. The above conclusion stays valid when different sets of published lung NTCP model parameters were used. No correlation was observed between the ΔTCP/ΔNTCP and the PTV size or location.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Arkansas Medical Science Institutional Review Board (FWA00001119).

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

References

Lyman JT. Complication probability as assessed from dose-volume histograms. Radiat Res. 1985;104 Suppl. 8:S13–9.

Lyman JT, Wolbarst AB. Optimization of radiation therapy, III: A method of assessing complication probabilities from dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat OncolBiol Phys. 1987;13:103–9.

Kutcher GJ, Burman C. Calculation of complication probability factors for non-uniform normal tissue irradiation: the effective volume method. Int J Radiat OncolBiol Phys. 1989;16:1623–30.

Burman C, Kutcher GJ, Emami B, Goitein M. Fitting of normal tissue tolerance data to an analytic fuction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):123–35.

Kutcher GJ, Burman C, Brewster L, Gotein M, Mohan R. Histogram reduction method for Calculation complication probabilities for three dimensional treatment evaluation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):137–46.

Källman P, Agren A, Brahme A. Tumour and normal tissue responses to fractionated non-uniform dose delivery. Int J Radiat Biol. 1992;62(2):249–62.

Schultheiss TE, Orten CG. Models in radiotherapy: definition of decision criteria. Med Phys. 1985;12(2):183–7.

Morrill SM, Lane RG, Jacobson G, Rosen II. Treatment planning optimization using constrained simulated annealing. Phys Med Biol. 1991;36(10):1341–61.

Qi XS, Semenenko VA, Li XA. Improved critical structure sparing with biologically based IMRT optimization. Med Phys. 2009;36(5):1790–9.

Das S. A role for biological optimization within the current treatment planning paradigm. Med Phys. 2009;36(10):4672–82.

Doit Q, Kavanagh B, Timmerman R, Miften M. Biological-based optimization and volumetric modulated arc therapy delivery for stereotactic body radiation therapy. Med Phys. 2012;39(1):237–45.

Allen Li X, Alber M, Deasy JO, Jackson A, Ken Jee KW, Marks LB, et al. The use and QA of biologically related models for treatment planning: short report of the TG-166 of the therapy physics committee of the AAPM. Med Phys. 2012;39(3):1386–409.

Ulmer W, Pyyry J, Kaissl W. A 3D photon superposition/convolution algorithm and its foundation on results of Monte Carlo calculations. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50(8):1767–90.

Lewis EE, Miller WF. Computational Methods of Neutron Transport. New York: Wiley; 1984.

Ahnesjö A, Aspradakis MM. Dose calculations for external photon beams in radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44(11):R99–155.

Vassiliev ON, Wareing TA, McGhee J, Failla G, Salehpour MR, Mourtada F. Validation of a new grid-based Boltzmann equation solver for dose calculation in radiotherapy with photon beams. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55(3):581–98.

Bush K, Gagne IM, Zavgorodni S, Ansbacher W, Beckham W. Dosimetric validation of Acuros XB with Monte Carlo methods for photon dose calculations. Med Phys. 2011;38(4):2208–21.

Fogliata A, Nicolini G, Clivio A, Vanetti E, Mancosu P, Cozzi L. Dosimetric validation of the Acuros XB Advanced Dose Calculation algorithm: fundamental characterization in water. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56(6):1879–904.

Kan MW, Leung LH, Yu PK. Verification and dosimetric impact of Acuros XB algorithm on intensity modulated stereotactic radiotherapy for locally persistent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Med Phys. 2012;39(8):4705–14.

Han T, Mikell JK, Salehpour M, Mourtada F. Dosimetric comparison of Acuros XB deterministic radiation transport method with Monte Carlo and model-based convolution methods in heterogeneous media. Med Phys. 2011;38(5):2651–64.

Moiseenko V, Liu M, Bergman AM, Gill B, Kristensen S, Teke T, et al. Monte Carlo calculation of dose distribution in early stage NSCLC patients planned for accelerated hypofractionated radiation therapy in the NCIC-BR25 protocol. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55(3):723–33.

Elmpt WV, Ollers M, Velders M, Poels K, Mijnheer B, Ruysscher DD, et al. Transition from a simple to a more advanced dose calculation algorithm for radiotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): implications for clinical implementation in an individualized dose-escalation protocol. Radio Ther Oncol. 2008;88(3):326–34.

Vanderstraeten B, Reynaert N, Paelinck L, Madani I, De Wagter C, De Gersem W, et al. Accuracy of patient dose calculation for lung IMRT: A comparison of Monte Carlo, convolution/superposition, and pencil beam computations. Med Phys. 2006;33(9):3149–58.

Fogliata A, Nicolini G, Clivio A, Vanetti E, Cozzi L. Critical appraisal of Acuros XB and Anisotropic Analytic Algorithm dose calculation in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treatments. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):1587–95.

Rana S, Rogers K, Pokharel S, Cheng C. Evaluation of Acuros XB algorithm based on RTOG 0813 dosimetric criteria for SBRT lung treatment with RapidArc. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2014;15(1):4474.

Kroon PS, Hol S, Essers M. Dosimetric accuracy and clinical quality of Acuros XB and AAA dose calculation algorithm for stereotactic and conventional lung volumetric modulated arc therapy plans. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:149.

Timmerman R, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, Papiez L, Tudor K, DeLuca J, et al. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4833–9.

Seamless Phase I/II Study of Stereotactic Lung Radiotherapy (SBRT) for Early Stage, Centrally Located, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) in Medically Inoperable Patients. https://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=0813. Accessed date: 6 Aug 2015.

Mutter RW, Liu F, Abreu A, Yorke E, Jackson A, Rosenzweig KE. Dose-volume parameters predict for the development of chest wall pain after stereotactic body radiation for lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(5):1783–90.

Joiner MC, Bentzen SM. Time-dose relationships: the linear-quadratic approach. In: Steel GG, editor. Basic clinical radiobiology. London: Edward Arnold; 2002.

Petillion S, Swinnen A, Defraene G, Verhoeven K, Weltens C, Van den Heuvel F. The photon dose calculation algorithm used in breast radiotherapy has significant impact on the parameters of radiobiological models. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2014;15(4):4853.

Willner J, Baier K, Caragiani E, Tschammler A, Flentje M. Dose, volume, and tumor control prediction in primary radiotherapy of non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(2):382–9.

Martel MK, Ten Haken RK, Hazuka MB, Kessler ML, Strawderman M, Turrisi AT, et al. Estimation of tumor control probability model parameters from 3-D dose distributions of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 1999;24(1):31–7.

Guckenberger M, Wulf J, Mueller G, Krieger T, Baier K, Gabor M, et al. Dose-response relationship for image-guided stereotactic body radiotherapy of pulmonary tumors: relevance of 4D dose calculation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):47–54.

Niemierko A. A generalized concept of equivalent uniform dose (EUD). Med Phys. 1999;26:1100.

Seppenwoolde Y, Lebesque JV, de Jaeger K, Belderbos JS, Boersma LJ, Schilstra C, et al. Comparing different NTCP models that predict the incidence of radiation pneumonitis. Normal tissue complication probability. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(3):724–35.

Kwa SL, Lebesque JV, Theuws JC, Marks LB, Munley MT, Bentel G, et al. Radiation pneumonitis as a function of mean lung dose: an analysis of pooled data of 540 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42(1):1–9.

Scheenstra AE, Rossi MM, Belderbos JS, Damen EM, Lebesque JV, Sonke JJ. Alpha/beta ratio for normal lung tissue as estimated from lung cancer patients treated with stereotactic body and conventionally fractionated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(1):224–8.

KruskalHK WWA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;47(260):583–621.

Sikora M, Muzik J, Söhn M, Weinmann M, Alber M, Monte Carlo V. pencil beam based optimization of stereotactic lung IMRT. Radiat Oncol. 2009;12(4):64.

Guckenberger M, Wilbert J, Krieger T, Richter A, Baier K, Meyer J, et al. Four-dimensional treatment planning for stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(1):276–85.

Marks LB, Bentzen SM, Deasy JO, Kong FM, Bradley JD, Vogelius IS, et al. Radiation dose-volume effects in the lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3 Suppl):s70–6.

Nielsen TB, Wieslander E, Fogliata A, Nielsen M, Hansen O, Brink C. Influence of dose calculation algorithms on the predicted dose distribution and NTCP values for NSCLC patients. Med Phys. 2011;38(5):2412–8.

Bufacchi A, Nardiello B, Capparella R, Begnozzi L. Clinical implications in the use of the PBC algorithm versus the AAA by comparison of different NTCP models/parameters. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8(1):164.

Rana S, Rogers K. Radiobiological impact of Acuros XB dose calculation algorithm on low-risk prostate cancer treatment plans created by RapidArc technique. Austral-Asian J Cancer. 2012;11(4):261–9.

Padmanaban S, Warren S, Walsh A, Partridge M, Hawkins MA. Comparison of Acuros (AXB) and Anisotropic Analytical Algorithm (AAA) for dose calculation in treatment of oesophageal cancer: effects on modelling tumour control probability. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:286.

Park C, Papiez L, Zhang S, Story M, Timmerman RD. Universal survival curve and single fraction equivalent dose: useful tools in understanding potency of ablative radiotherapy. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2008;70(3):847–52.

Park HJ, Griffin RJ, Hui S, Levitt SH, Song CW. Radiation-induced vascular damage in tumors: implications of vascular damage in ablative hypofractionated radiotherapy (SBRT and SRS). Radiat Res. 2012;177(3):311–27.

Song CW, Cho LC, Yuan J, Dusenbery KE, Griffin RJ, Levitt SH. Radiobiology of stereotactic body radiation therapy/stereotactic radiosurgery and the linear-quadratic model. Int J Radiat OncolBiol Phys. 2013;87(1):18–9.

Chapet O, Kong FM, Lee JS, Hayman JA, Ten Haken RK. Normal tissue complication probability modeling for acute esophagitis in patients treated with conformal radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77(2):176–81.

Martel MK, Sahijdak WM, Ten Haken RK, Kessler ML, Turrisi AT. Fraction size and dose parameters related to the incidence of pericardial effusions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40(1):155–61.

AgrenCronqvist AK, Källman P, Turesson I, Brahme A. Volume and heterogeneity dependence of the dose-response relationship for head and neck tumours. Acta Oncol. 1995;34(6):851–60.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support by University of Nebraska Medical Center for funding Open Access Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XL conceived of the study, participated in the design of the study, carried out the studies and drafted the manuscript. JP conceived of the study, participated in the design of the study, provided clinical expertise and helped to draft the manuscript. DZ participated in the design of the study, data analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. SM and XZ helped the analysis and drafting of the manuscript, PC and RG helped in the radiobiological modelling and drafting of the manuscript, EH and MH involved in the discussion and helped the manuscript. VR involved in the discussion provided clinical expertise and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, X., Penagaricano, J., Zheng, D. et al. Radiobiological impact of dose calculation algorithms on biologically optimized IMRT lung stereotactic body radiation therapy plans. Radiat Oncol 11, 10 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-015-0578-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-015-0578-2